-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Erkin Koray R.I.P.

By Jay Dobis

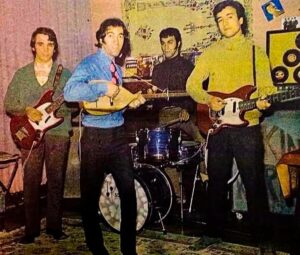

Erkin Koray, aka Erkin Baba, the father of Turkish Rock ‘n Roll (he put together the first Turkish rock band (Erkin Koray ve Ritmcileri) in 1957 when he was a high school student in Istanbul, died at the age of 82 on Monday, August 7. He had been living in Toronto, Canada for a while and had been hospitalized due to lung problems.

After a mandatory stint in the army, Erkin started playing out and became a popular live attraction. In 1962, he released his first single: “Bir Eylül Akşamı”/”It’s So Long.” In 1967, he had his first hit record: “Kızları da Alın Askere” (Let Girls Join the Army), which quickly sold 800,000 copies in a country of only 30 million people (70% lived in rural areas). His next release, “Meçhul/Çiçek Daği” (also in 1968) came after his band finished fourth in Hürriyet newspaper’s Altın Mıkrofon contest… In 1969, Erkin Koray & Yeraltı Dörtlüsü (Underground Quartet), released “Sana Bir Şeyler Olmuş,” the greatest version of the Cannibal & the Headhunters song “Land of a Thousand Dances.” And I mustn’t forget his magnificent, crunching track from 1972, “Hor Görme Garibi” (by Erkin Koray ve Ter, which included guitarist Aydın Cakuş (formerly of Grup Bunalim) on sizzling guitar).

Against his objections, in 1973 his label Istanbul Plak, released an album called Erkin Koray, which collected his singles… In 1974, Doğan Plak released Elektronik Türküler, which Erkin considered his first album. It is his masterpiece and is one of the greatest psychedelic albums ever recorded. The core group (Erkin on guitar and bağlama, Ahmet Güvenç on bass, Sedat Avcı on drums) were augmented by Haci Ahmet Tekbilek (who would soon move to Scandinavia to play in Okay Temiz’s great Turkish jazz bands of the 1970s on zurna and gaida), Omer Faruk Tekbilek (a future world music star) (bağlama), Eyüp Duran (bongos), and Ayzer Danga (drums) from Moğollar and Mavi Işiklar. The album fully integrates rock with traditional Turkish folk music: great originals; a cover of a traditional folk tune; and a cover of Ürgüplü Refik Başaran’s “Cemalin.” My two favorite songs on the album are the original “Inat,” with searing psychedelic guitar, and “Türkü,” a cover of a Nazim Hikmet poem that had originally been set to music by saz player Rui Su. This album cemented Erkin’s reputation as an Anadolu Rock legend, blending Turkish classical music, folk tunes, and various Middle Eastern sounds into his psych driven songs. Erkin also claimed to be the inventor of the elektro-saz; he was certainly one of the first and popularized the instrument.

His next album, Erkin Koray 2, released in 1976, was almost as good, putting even more emphasis on Arabic influences, particularly on my favorite song by Erkin, “Şaşkın.” Other greats on this album are “Fesuphanallah,” “Estarabim,” “Arap Sacı,” and “Timbıllı.” His last excellent album (though he continued to have more great singles) came in 1983: İlla Ki, which shows the influence of the American band The Devil’s Anvil. (Knowing that his life was nearing its end, Erkin wrote a letter to music writer Kanat Atkaya, claiming that there was no such influence calling The Devil’s Anvil an ‘amateur’ band, and that he had never heard their album, that he is ERKIN KORAY, and that those who think otherwise should look to ASCAP for clarification. He also discussed his meeting with John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival.)

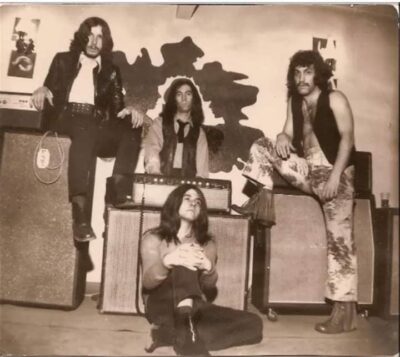

In the early and mid ‘70s, in concert Erkin would typically do two sets. The first would consist of covers of songs by bands such as Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, and Atomic Rooster. In the second set, he would play his own superior songs… At some point in the early ‘70s, he planned to record an album of what he described as ‘space rock,’ but unfortunately his label refused to pay for studio time.

Throughout his career he was known to be a ‘different kind of guy,’ most probably due to the ill treatment he received from record label owners whom he frequently quarreled with and sued in court. He was even bootlegged in his own country. Over the years I heard many stories about his ‘crazy’ actions. However, for about 12 years, I was in occasional contact with Erkin: hanging out with him, talking about music, talking on the telephone, having dinner, inviting him to see the band I was managing (ZeN), etc. And he always was very nice and normal.

Even in the US, he had bad luck with record labels. In 1996, an American label was set to release a 3-CD set called Erkin Koray: Turkish Psych Monster. The label had Erkin’s permission, and he would have been paid. Extensive liner notes were written and numerous photos were to be included. However, these CDs were never released due to threatened lawsuits by another label that was releasing an Erkin album without his permission. So in America, now you have to settle for the competent but lacking collection on Sublime Frequencies, which doesn’t match the quality and number of rarities that would’ve been available on the Turkish Psych Monster set.

A few years later, a different American label was to release Erkin Koray: Live in Nazilli, which is my all-time favorite live album. On an Aegean tour with his Süper Grup, a power trio with Nihat Örerel on drums (a former member of Grup Bunalim, Nihat also cowrote some of Erkin’s greatest songs) and Rauf Ülgün on bass. Nihat recorded every show during the tour on a cheap boom box as a reference tape. So the songs on the album are what was left on the tape after the end of the tour. For the album release, the sound quality was to be cleaned up in a studio, including fixing pitch problems, and excellent liner notes had been written. Unfortunately, a certain miscreant uploaded the concert tape to YouTube, and the album was never released, though it has since been bootlegged.

For a book about Erkin 26 years ago I wrote a short chapter and called him a greater psychedelic musician than Jimi Hendrix, and I still believe this… Although Erkin has died, his eastern modal raga rock lives on.

Remembering Michael Nesmith

By Michael Lynch

“The one with the hat… “the one whose mother invented liquid paper”… “the one who didn’t do the reunion tours with the others”… “The one who pioneered country rock”… “the one who sowed the seeds for what became MTV”… “the one who led the fight for musical creative control for his band” are some of the ways he’ll be remembered. Or simply as the one directly responsible for a good-sized chunk of the Monkees’ musical pleasures and treasures.

The Monkees’ multi-talented singer songwriter and guitarist Michael Nesmith died of heart complications on December 10, 2021, a few weeks shy of his 79th birthday. Fellow Monkees Davy Jones and Peter Tork passed in 2012 and 2019 respectively. Only Micky Dolenz now survives.

All four Monkees had their unique traits, but right from the beginning, Nez stood out, both onscreen, with his signature wool hat, and cool collected demeanor displayed on their popular 1966 to 1968 TV series establishing him as the foursome’s leader, the smart one, and the one to take charge when the situation required, and offscreen, for Mike, who (like Davy) had already released a few singles released on Colpix Records, a branch of the Columbia and Screen Gems family tree, was writing and producing songs for the band’s records as early as the very first album, at the same time seeing his compositions recorded by other artists, notably “Mary Mary” being tackled by the Butterfield Blues Band and later “Different Drum” bringing Linda Ronstadt, by way of the Stone Poneys, her first visit to the upper regions of the charts.

The Monkees’ records sold millions, but Mike, horrified by some of the songs chosen by their musical supervisor Don Kirshner and resentful of the use of studio musicians providing the instrumentation instead of the Monkees (and smarting from the outcry and scorn once this became known to the public) sought to turn things around. He led his three bandmates in a bumpy, contentious but ultimately successful coup against the powers that be to give the Monkees musical control and have Kirshner dismissed. Fans can (and do) debate whether the Monkees were wise to rock the boat, but Nesmith followed his heart and creative instincts.

Traces of country influence could be detected as early as Mike’s songs on the Monkees’ first album, and as the years went on, Mike worked harder at balancing country with rock, improving as he went, by decade’s end all but providing the blueprint for ‘70s bands like Poco and Eagles (while Mike’s post-Monkees combo the First National Band continued down said course).

For decades Mike appeared reluctant to embrace his Monkee past, more keen on moving. Micky, Peter and Davy reunited in 1986 but Mike only appeared with them sporadically. He rejoined them to work as a foursome in 1996 for an album and a European tour the following year, but immediately jumped ship at that tour’s completion. The four never worked together again. Following Davy’s 2012 passing, Mike teamed up with Peter and Micky for a series of tours, and from then on right up to one month before his death, Mike was more often than not an active Monkee once again.

Close associates of Mike claim that in his final years Mike had achieved a fuller appreciation of what an impact the Monkees had made on so many. Perhaps in his mind he echoed his 1968 sentiments: “Here I stand, happy man.”

NOTABLE NEZ: TEN OF MIKE’S MEMORABLE MONKEE-SHINES

Everybody knows “Mary Mary,” “Listen to the Band” and “You Just May Be the One,” but Nez had plenty more delights up his hat. Here are ten other examples of Mike’s Monkees-era. Not necessarily his ten finest, but ten that taken together provide a decent summary of what, stylistically, Mike brought to the table:

SUNNY GIRLFRIEND (from Headquarters, 1967)

Dip the Rolling Stones’ “It’s All Over Now” in sunshine and add a touch of their unfinished early 1967 versions of “She’s So Far Out She’s In” (an early live favorite) and you have this upbeat gem that represents one third of Mike’s (wool) hat-trick of Headquarters highlights.

DON’T CALL ON ME (from Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones, Ltd, 1967)

Pisces had a higher percentage of Nesmith-related tracks than any other Monkees album, with many songs spotlighting him as either lead vocalist or songwriter. “Don’t Call On Me” was the album’s only song on which he was both. The song dated back to Mike’s earlier days as a folk singer, and tasteful recordings exist of his trio Mike, John & Bill doing the song in a gentle acoustic manner. For the Monkees’ version, the song is slightly amped up with increased instrumentation, but still kept gentle.

DAILY NIGHTLY (from Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones, Ltd, 1967)

Although Micky stars on this trippy track as lead vocalist and Moog player (one of the very first on a rock record,) the song itself came from Mike’s pen. His reflections of late 1960s Sunset Strip stand as some of his most poetic lyrics. Phantasmagoric splendor indeed.

CARLISLE WHEELING (recorded 1967, unreleased until Missing Links, 1987)

Mike recorded this song several times in his career. Attempts in 1967 and 1968 for the Monkees, once for his ambitious 1968 instrumental album The Wichita Train Whistle Sings, and then as “Conversations” for his 1970 post-Monkees album Loose Salute. To the ears of this writer, he captured it best the first time.

MAGNOLIA SIMMS (from The Birds, the Bees & the Monkees, 1968)

The same month Moby Grape Wow’d us with a simulated old-timey 78, so did the Monkees. “Magnolia Simms,” thanks to built-in surface noise, intentional scratches, and monaural sound panned to one channel (all explained in a back cover disclaimer) succeeds in, as Mike intended, capturing “the sound of the 1920-30 yippies.”

TAPIOCA TUNDRA (from The Birds, the Bees & the Monkees, 1968)

Originally found on the flip of “Valleri” before eventually finding its album home was what ultimately became the highest-charting Monkees song of his authorship, peaking at #34. A breezy charming mix of melody, whimsy and psychedelia…imagine “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” slightly faster, on acid.

SAINT MATTHEW (recorded 1968, unreleased until Missing Links Volume 2, 1990)

Do country and psychedelia blend well? They sure do on this originally-shelved track. The fiddles and twangy guitar combine fabulously with the organ and Leslie’d vocal of trippy lyrics, as if someone dosed the punchbowl at a hoedown.

NAKED PERSIMMON (from TV special 33 &1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee, taped late 1968)

Nothing demonstrated the two sides of Michael Nesmith better than his (sort of) solo spotlight scene of the Monkees’ infamous 1969 TV special. In an amusing split screen performance, hip electric guitar-toting Nesmith performs alongside a cowboy version of himself on a song that takes turns alternating between both musical styles. In addition to being one of the special’s more entertaining moments, it also accurately summed up where Nez was musically at.

WHILE I CRY (from Instant Replay, 1969)

Monkees fans long held this gorgeous tearjerker close to their hearts and were delighted when Nez revived it in 2021. The performances proved the earnestness of his delivery had not diminished over the 52-year gap.

GOOD CLEAN FUN (from The Monkees Present, 1969)

The final Monkees single while Mike was aboard was this country-drenched toe-tapper which lived up to its title. With health issues of Mike’s forcing an abrupt halt of his and Micky’s 2018 tour and causing great concern from fans, subsequent live performances of this song proved particularly poignant when Mike reached the thrice-sung final line “I told you I’d come back…here I am.”

Large as Life & Twice as Loud

Mike Brassard of Mike & The Ravens: January 15, 1943 – November 27, 2021

By Will Shade

Buddy Rich – or someone like him – once said, “It ain’t bragging if you can back it up” or words to that effect… but what if you’re not bragging. What if you actually try to hide your light under a bushel but it always explodes like a geyser of Roman candles? What if the moment you open your mouth in either conversation or song, people come to a halt and at the very least say to themselves, “Whoa, what in the world is this?”

That was Mike Brassard. He oozed charisma like mustard on a clean white shirt. He couldn’t help himself.

You were larger than life, Mike, and twice as loud. And you’ll always take twice as much room in my heart as anybody else.

So, how can I say goodbye to my best friend? How do I say goodbye to my brother from another mother? How do I say goodbye to a father figure? And how do I say goodbye to a guy I played air guitar with, a guy who was 25-years-older than me, but we both grinned like insane fools with Link Wray cranked to maximum volume as we danced our keisters off around the studio?

Well, you don’t say goodbye… you say hello to the memories, and there were so many memories…

He called himself the Big Bopper… I said he was a rock ‘n’ roll citizen in a hip-hop world.

I’d tracked Mike down in 2004 as I was putting together a compilation of pre-Beatles rock ‘n’ roll from New York and Vermont. While Mike wanted to tout the songs of his erstwhile partner, Steve Blodgett, he was reluctant to open up in regard to his own abilities. Anybody who knows me, though, knows that’s a futile endeavor. Before too long, I was flying down to Florida to spirit him north and into the confines of the Saxony Recording Studios.

It was that willingness to squelch his own genius that actually brought his character into sharper focus.

I miss Mike’s generosity of spirit… but mostly I miss his sense of humor… I remember him explaining what it was like to be the nominal adult in a band with Blodgett, Lyford and Young back in 1962.

“It was like babysitting the Three Stooges,” he said… there was no meanness in it… it was simply a statement of fact with some levity thrown in.

I won’t be saying goodbye to Mike. Daily I’m reminded of him. Yesterday I was watching a documentary on Sun Studios. My first instinct was to send him an email, raving about Jerry Lee Lewis… but then I remembered there was nobody on the other end of the line… I sent the email anyway.