-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers -

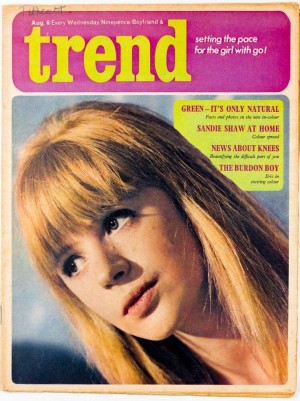

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

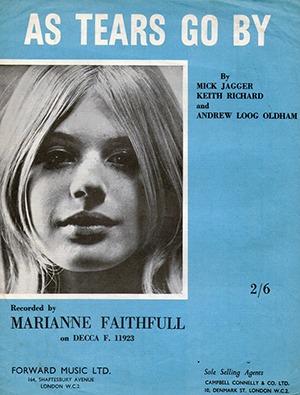

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1963-1967 record producer and manager of the Rolling Stones, for Discoveries magazine. “The fact is forgotten that Marianne had, between August of ‘64 and the summer of ‘65 four Top Ten hits in the UK. ‘As Tears Go By’ and ‘Come And Stay With Me’ held up.”

“As Tears Go By” is a song penned by Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Andrew Loog Oldham. It reached a top ten position in the UK singles chart. The Stones then recorded their own version, included on the American pressing of December’s Children (And Everybody’s) in 1965. Their American record label London issued “As Tears Go By” as a single that landed in the number six spot on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

It was Marianne who gave Mick the book which inspired the song “Sympathy for the Devil.” In the 2012 Rolling Stones documentary, Crossfire Hurricane, Jagger acknowledged his influence for the composition was informed from French poet Pierre Baudelaire and the Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita. An English translation was made available in 1967. The song is heard on Beggars Banquet, produced by Jimmy Miller and engineered by Glyn Johns and Eddie Kramer in London at Olympic Sound Studios. Marianne is one of the backing vocalists on the recording.

Marianne went on to record more than twenty solo records, including the acclaimed 1979 album Broken English, and 2018’s Negative Capability, which included collaborations with Keith Richards and Nick Cave.

In the early ’90s Marianne was made a professor by Allen Ginsberg at the Naropa Poetry Institute in Colorado, where she has taught lyric writing. Her certificate reads: Marianne Faithfull, Professor Of Poetics, Jack Kerouac School Of Disembodied Poets.

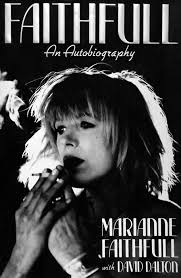

During 1994, Marianne Faithfull had a new album out, A Secret Life, a collaboration with producer/arranger /co-writer Angelo Badalamenti (best known for his working relationship with filmmaker David Lynch, including orchestrating the music for Twin Peaks). Island Records at the time also released Faithfull: A Collection Of Her Best Recordings, and in 1994, Little Brown published her candid terrific memoir, with David Dalton, Faithfull: An Autobiography.

It was Allen Ginsberg, who encouraged me to look Marianne Faithfull up the next time she was in Hollywood. I was given an interview assignment for HITS magazine. Marianne’s publicist at Island Records arranged for me to visit her on Sunset Boulevard at the Chateau Marmont.

So in 1995 I knocked on the door to Marianne’s hotel room at the Chateau Marmont, ironically, right next to the suite where years earlier I had interviewed and had lunch with Leonard Cohen.

Marianne answered my knuckles, “Welcome to the poet’s corner,” she beamed.

I looked at her for about thirty seconds. She had big green eyes. Clad in black. Not punk black, but black blouse, black pants and black nylons. Marianne was an image out of Hollywood’s Jazz City music club circa 1958, a cinema noir sister of Susan Oliver and Gloria Grahame. She wore no makeup, blonde, long hair, a little shorter in person that I expected. She had a dancer’s body. In fact, twice during the two-hour chat, she leaped off the couch onto the rug and sort of did a move, an interpretation of “the sideways pony” dance that Tina Turner once taught Mick Jagger in the hall way in front of her in 1965 at Colston Hall in Bristol, England. She told me her mother Eva taught her to dance as a child.

I then mentioned that I briefly danced on American Bandstand as a teenager in May of 1966.

She was rather impressed.

“Whew…Remind me to give you a kiss and a hug when you leave today and don’t worry if my boobs get in the way,” she comically warned. “No problem,” I assured her.

Room service delivered Marlboro Lights. Marianne also ordered a vodka martini for our smoky conversation. I had a mineral water. The record label paid.

Marianne was very supportive to me when I complained about not getting a book deal. A decade later she had a chapter in my first book This is Rebel Music, published in 2004.

This still alluring Marianne Faithfull turned out to be a fascinating interview subject and a real yenta. She was a lot of fun and never avoided a question during our time together.

I got from your autobiography you were a poetry head.

Always. That’s one of the reasons I love Allen so much and William Burroughs.

Needless to say, one of the things that drew you to the music and word work of Bob Dylan. I noticed you were in one of the hotel room scenes in Dylan’s Dont Look Back film that chronicled his 1965 British tour. In your book in the Dylan Redux chapter, you provide a real cool glimpse of Dylan in action in the mid-60’s and then years later. I thought it was one of the sections where you and David Dalton worked really hard in bringing the moment to the reader.

I think that was the bit that David did best. I didn’t work the hardest on that, David did. But it was wonderful. I wish he’d written the whole book like that. And all the Bobby Newirth stuff was so beautiful.

Had you never seen a rock person like Dylan or an American like him in 1965?

Never. Never in my wildest dreams could have imagined anyone like Bob in 1965. His brain. But I was frightened. I didn’t know they were probably more scared of me. I don’t know. They were all on methedrine. He played me the album Bringing It All Back Home himself on his own. It was just amazing. And I worshipped him anyway. That was where I got very close to Allen Ginsberg ‘cause Allen was the only sort of person I could recognize as being somewhat like me.

I really enjoyed the passage in your book when Allen came to London with the Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti. They read at Queen Elizabeth Hall. You had spent some time with Ginsberg during Dylan’s Dont Look Back tour and I laughed out loud as you described inviting Allen to the house you shared with Mick Jagger. Great image and a very fortunate position for you as Ginsberg sat on your bed with you and Mick naked under a fur cover.

As you put it, “Allen, as usual, was on a mission. Allen was trying to get Mick to put William Blake’s ‘The Grey Monk’ to music.” Again, until this book, I never knew you had such a jones for poetry, and beat generation poets.

(Smiles. I find them very sexy all those guys. Wonderful. I teased Allen in my book. I adore him. The first time I went to Naropa, Allen was literally by my side like he is. There was a lot of criticism and “Who is the woman?” “Why do you (Allen) think she can do this?” And he didn’t say anything. “I just do.” And then I came back again. We are very good friends. He also represents a lot of things for me that aren’t part of our friendship or our relationship. He is the greatest living American poet. I hooked Allen up with [producer] Hal Willner.

How did your autobiography come together? I know you’ve been approached over the years and obviously film adaptations are being offered on this book and your life.

It took a long time. I have great recall.

Why did you do the book?

I did it for you. (laughs). I did. I felt there was something in the story that was very common to everybody. I do believe that the details and the individuals are different, but the emotions and the sort of core thing are very, very connected to all human experience. Therefore, I felt it was a valid story to tell. And then again, I felt I was very close to some of the greatest people of my time. And I had a lot of help.

David Dalton came to Ireland for two weeks. He’s a very shy person. He selected me. Such a strange story. Tony Secunda – who recently died, I dedicated my paperback English edition to him – he had become a literary agent, and he was working with Dalton and he came to Ireland. I didn’t want to do this book, really. Much as I care for humanity…

And he picked David Dalton who was a big Rolling Stones fan.

That was peculiar for me. And my great tease. I would tell David at first, that what I saw in him as a writer was that he was basically a necrophilliac. “You have only written books about dead people. (James Dean, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison). How are you going to cope with someone who is not dead and not likely to be dead?”

And being a woman with opinions.

But David liked that.

But I’m sure you also gave a view and observations of your life and art process that were different than the myth and history events captured so far in the Rolling Stones documentation.

It took him a long time to believe me. I have to stand up for David because it wasn’t as simple as that. Yes, he was a Rolling Stones fan, but that in itself shouldn’t be a problem.

The interviews went on for hours.

And for once, you had the opportunity and forum to tell your side of the story. The truth you saw and experienced. You were in control.

Well I didn’t realize that, ya know. That’s what made it so hard for Dalton. He kept saying to me, “This is your book! This is your thing! I will only do what you want.” But I didn’t believe him.

Was it your intent in the book, and specifically this Dylan chapter to be so detail oriented about the environment? Obviously, you were doing a memoir. I know for a fact there are some scenes that went down that you could not invent unless you were there. And, I even feel it on the printed page.

Of course, I was there! I ended up adoring David. He’s one of my best friends now.

Did photos trigger recall of events?

No. I’ve been carrying this around for a long time. And I had remembered the things that were important to me which were always the same. It was always very, very clear that what I was really interested in and always had been interested in was motive and psychic position and why. There were a million things I could not remember, which are not interesting to me.

What was it like seeing the galleys? The first typeset manuscript?

That was heavy. (sighs). That was when I also saw the pictures. My editor came over with the pictures. That was one of the harder bits.

Did you take things out at that point?

Yes. It wasn’t legalities. There were some mistakes and I could not have them.

Was it hard during the interviews and the collaboration with David Dalton to tell your point of view? I would imagine you had to at times be combative.

Yes. I thought it was really good for me and about fuckin’ time I learned to do that. I didn’t want to. I resisted it but I had to. I had to. David is married to a very intelligent woman Coco and she really worked very closely with him and I think it had some impact. It was much harder work than David had ever done before. A living person.

In your book you mention some of the Rolling Stones characters in their songs came to life partially owing to acid.

Of course they did. I don’t think acid is relative or relevant anymore. I wouldn’t do it again. But I think that it was important then, and I think it taught us a lot.

They were all very much in love with me at that time. Not only me, but I was one of the many women they were in love with. Keith and I are still very close. I’m under his wing and I know I will always be under his wing.

Brian wasn’t as bad as everybody thinks. Well, Brian was a genius, but he was a very irritating person. Keith really loved Brian. I use Brian. I have a whole lot of friends on the other side that I call up when I need them. I use Brian, Janis and now I’ve got Tony Secunda and Denny Cordell.

I cut out some things about Brian Jones. He went on and on and made him much more of a worse person than he was. He could only do that really because he was dead. He couldn’t go on and on about Keith and Anita or even me because I did the classic Buddhist thing: I just did a drive all blames into one. I made that decision. That is something I learned from Allen. I’ve had good Naropa training. The galleys were hard to read.

What is it like looking and reading the book?

I’ve read it and re-read it and it’s still hard…It’s hard to believe I’ve done it and that it’s really me and a part of me now. David did a good job, man. I have to say this.

Your book is now out in paperback. I just got a copy. Do you have any more feelings on it since publication?

I’m terribly pleased with it and proud of it. It’s like a child of mine that has gone out and done well. It’s a good read.

As a teenager in England you went to a Catholic School St. Joseph’s in Reading. And devoured a lot of books and studied poetry. But in your autobiography, I learned you’re Jewish.

My dear little Piscean, my mother and my grandmother were Jewish. My mother came from a line of Austro-Hungarian aristocrats. My mother was a doctor’s daughter. She was a Jewess, those great Jews who went out and did it from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Doctors, writers, sort of like going into Oklahoma. Allen Ginsberg now is my Jewish Mother.

© 2025 Harvey Kubernik

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015′s Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016′s Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017′s 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His book Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll Television Moments) is scheduled for 2025 publication.

During 2006 Harvey spoke at the special hearings by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 Kubernik appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series).

Col. Bruce Hampton (1947-2017)

By Alan Bisbort

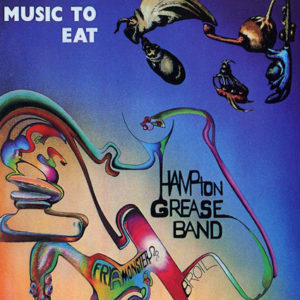

The first time I saw Bruce Hampton, he was standing on the tiny stage at a suburban Atlanta “teen scene” venue reading the contents off the side of can of spray paint. This was in 1968. A sweaty, short-haired guy in a button-down-collared shirt with the build of a middle linebacker, Hampton looked out of place accompanied by two guitarists, a bassist and drummer all with hair so long you could not see their faces and all of whom were playing as loud as fire engine sirens. Needless to add, I had never seen anything like it in my 15 years on this planet. Nor had the handful of other brave teens whose parents had dropped them off at the alcohol-free club in the shopping mall. A much larger crowd of teenyboppers were milling about in the parking lot outside, having been driven from the room by the psychedelic noise created by the Hampton Grease Band. Years later I learned this was just one of the many ill-advised gigs the band’s manager had secured for them prior to their signing a record deal with Columbia, which released their one and only album, the epic double-LP package Music to Eat. (On which was a cut called “Spray Paint”).

Not too long after that, the band—Hampton on vocals and dada vibes, guitarists Harold Kelling and Glenn Phillips, bassist Mike Holbrook and drummer Jerry Fields—began appearing at free shows in Piedmont Park, the downtown Atlanta hangout for hippies, druggies, bikers and most of the runaways in the southeastern US. Soon enough, on the strength of these monumental free gigs, the Hampton Grease Band would wow hundreds of thousands of “freaks” at the two Atlanta Pop Festivals and regularly share bills with Jimi Hendrix, the Allman Brothers Band, Grateful Dead and even Captain Beefheart & his Magic Band. Bruce was, in fact, a Southern-fried version of Don Van Vliet, with a warming touch of Sun Ra. To my fragile eggshell mind, Hampton, and his band, provided an epiphany of sorts—showing me that music could go beyond mere recitation of clichéd boogie lyrics and shoddy playing and take you to places you never expected to go.

The Hampton Grease Band carried on for a few years, then members drifted off to pursue their own musical muses. Phillips and Kelling went on to form their own bands (a live recording by Phillips’ band was favorably reviewed in UT #44). Over the next four decades, Hampton added the honorific “Colonel” to his name and recorded a few solo albums (including the unsurpassably strange One Ruined Life of a Bronze Tourist) and became a major force in the jam band subculture that flourished under the banner of H.O.R.D.E. He fronted several bands of his own, including the Aquarium Rescue Unit, Fiji Mariners and Codetalkers, and served as a mentor to many young, gifted players who’ve since gone on to productive musical careers.

In the 1990s, during one of his passes through Washington DC, where I then lived, Hampton contacted me through a mutual friend and I spent a day museum-hopping with Bruce and members of his band, one of the highlights of my 17 years in the nation’s capital. He was generous, funny, kind and subject to conversational turns on a dime. No wonder Billy Bob Thornton called Hampton (who appeared in his film Sling Blade) “the eighth wonder of the world.” Listening to Hampton on album (other than the indispensable Music to Eat) was not quite the same as seeing him live. I once saw him play a gig with a golf club in his hands, practicing his swing while his band jammed, and every so often going to the microphone to pronounce the word “hose.” Every concert was different, unpredictable, strange and beautiful.

Early in May, a veritable who’s who of Southern rock gathered for a sold-out 70th birthday celebration for Col. Bruce Hampton at Atlanta’s historic Fox Theater. At the end of the show, during the final encore (of “Turn on Your Lovelight”), Hampton collapsed on stage and died minutes later at a nearby hospital. The mourning could be heard all the way to New England, where I live now. Both of my sisters, who live in Atlanta, called to bring me the news, then high school friends I hadn’t heard from in years began contacting me. Eventually, the strangeness of Col. Hampton’s demise gave the story “legs” in print and on the Internet, propelling it even into the staid pages of the Wall Street Journal—providing Hampton more notoriety in death than he ever had in life. The consensus seems to be that he could not have had a more fitting exit, dying on stage like that.

For me, though, it’s just sad. Part of it is, no doubt, tied up with losing that personal connection to my youth, but so many musicians I admired have died before this and the sadness didn’t linger like this. With Hampton’s death, it’s as if a musical force were shut off, like a faucet or a hose. I had no delusions that he still had some musical masterpieces locked inside his fertile cranium. No, it’s clear now that HE was the masterpiece.

Twinkle 1948-2015

Twinkle (Lynn Annette Wilson-Rogers), singer and songwriter, born 16 July 1948, Surbiton, Surrey; died 21 May 2015, Isle of Wight.

By Alan Clayson

“Terry,” maiden single by Twinkle—who has died of cancer, aged 65—caught if not the mood, then a mood of 1964. Concerning a biker who, irked by his girl’s infidelity, zooms off to a lonely end of mangled chrome, blood-splattered kerbstones and the oscillations of an ambulance siren, it had been an instant cause célèbre. As well as distressing the BBC, it also suffered a banning on ITV’s Ready Steady Go, not for the death content so much as its non-conformity to the series’ Mod specifications—for there was no doubt about Terry’s identity. There was, however, some speculation about Twinkle’s: a London dolly-bird in her John Lennon cap, striped jumper and kinky boots—“I never wear anything except boots” ran one press release—singing about a leather boy with a greasy quiff. It was like West Side Story, wasn’t it: a Mod loving a Rocker?

Moreover, the upbringing of Lynn Annette Ripley—pet-named ‘Twinkle’ from birth—was centered on gentrified Kingston Hill where Surrey merges with London, and embraced chauffeurs, maids, meeting royalty – and a private education that she endured rather than enjoyed at Kensington’s select Queen’s Gate School. Other former students included the Redgraves and Camilla Parker-Bowles, the future Duchess of Cornwall.