-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

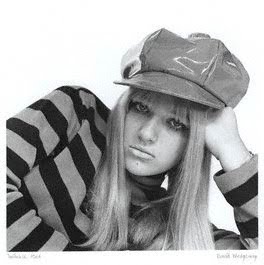

Twinkle 1948-2015

Twinkle (Lynn Annette Wilson-Rogers), singer and songwriter, born 16 July 1948, Surbiton, Surrey; died 21 May 2015, Isle of Wight.

By Alan Clayson

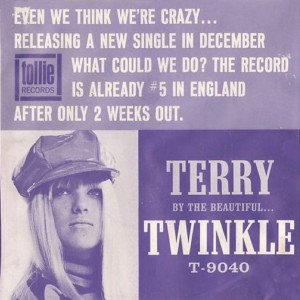

“Terry,” maiden single by Twinkle—who has died of cancer, aged 65—caught if not the mood, then a mood of 1964. Concerning a biker who, irked by his girl’s infidelity, zooms off to a lonely end of mangled chrome, blood-splattered kerbstones and the oscillations of an ambulance siren, it had been an instant cause célèbre. As well as distressing the BBC, it also suffered a banning on ITV’s Ready Steady Go, not for the death content so much as its non-conformity to the series’ Mod specifications—for there was no doubt about Terry’s identity. There was, however, some speculation about Twinkle’s: a London dolly-bird in her John Lennon cap, striped jumper and kinky boots—“I never wear anything except boots” ran one press release—singing about a leather boy with a greasy quiff. It was like West Side Story, wasn’t it: a Mod loving a Rocker?

Moreover, the upbringing of Lynn Annette Ripley—pet-named ‘Twinkle’ from birth—was centered on gentrified Kingston Hill where Surrey merges with London, and embraced chauffeurs, maids, meeting royalty – and a private education that she endured rather than enjoyed at Kensington’s select Queen’s Gate School. Other former students included the Redgraves and Camilla Parker-Bowles, the future Duchess of Cornwall.

Her father, Sidney, a prominent local politician, was an amateur songwriter, albeit with no interest in pop. He and his wife, a conservatoire-trained pianist, decided to formalize the musical talent that Twinkle betrayed when, as she recalled, “apparently, when I was three, I sat down at the grand piano in our drawing room, and played the National Anthem right through. That was the first time anyone realized that I had a natural ear. So my mother took me to see Sir Sidney Harrison (piano professor at the Guild Hall School of Music), and he said that if I continued the way I was going, I’d have a teacher’s diploma by the time I was twelve. He recommended a local piano teacher. I started playing in concerts when I was four – but I just got bored with it, and gave up when I was eight.”

A prototype ‘wild child’, Twinkle was to admit, “I didn’t have an image made up for me by a publicity department. All you saw was what I was. I’m very rebellious, and I was terrible anxious to get in with the fast crowd.” Thus she found herself microphone in hand during one frolicsome 1963 evening at Esmeralda’s Barn, a west London night spot. Her looks and personality as much as her singing landed her a weekly spot as ‘featured vocalist’ with resident two-guitars-bass-drums quartet, the Trekkers.

If Twinkle’s subsequent pop career was to be shorter than the Sandie Shaws and Marianne Faithfulls of the era, she was less of a marionette as most other female singers of the era seemed to be, composing the A-sides of her hits herself—thus pre-empting the likes of Joni Mitchell and Melanie by at least six years. “I wrote ‘Terry’ during a particularly tedious French lesson at school. It was about somebody I wanted to meet but never did.”

An entrée into the record industry came via her elder sister Dawn whose literary talents had led her to become a leading pop journalist, working for IPC, Mirabelle and Rave!, and serving as feature writer for 19 magazine. Accompanying Dawn to numerous show business parties, Twinkle acquired an admirer in Dec Cluskey of the Bachelors, who played her demo of “Terry” to the Irish trio’s managers, Philip and Dorothy Solomon. Sensing a potential smash, Philip, a powerful mid-1960s impresario, visited the Ripleys where, after committing a faux pas by mistaking Twinkle for one of the servants’ offspring, his enthusiasm for “Terry” and predictions of a golden future for Twinkle proved cautiously contagious in that she had to promise to attend finishing school if the record missed. Seized by Decca, she was backed by a session crew that included guitarists Big Jim Sullivan and Jimmy Page.

Copious plugging on pirate radio provoked the headline “Drop The Death Disc, Johnny!” from Melody Maker, and Lord Ted Willis’ condemnation of “Terry” as “dangerous drivel.” How, therefore, could it miss? Sent in its way with pieces in Mirabelle—that added a year to Twinkle’s age—and a television debut on ITV’s Thank Your Lucky Stars, it came within an ace of Number One in the domestic chart—and was a hit overseas too, notably in Australasia and Canada.

It was still in the Top 30 when the 16-year-old undertook the first of many round-Britain package tours, one of them headlined by the Rolling Stones: “My parents insisted that a uniformed nanny went too as the guardian of my innocence. Mick (Jagger) was always amused when he noticed her in the front row, rooting for me and the Stones.”

Adulation on these shows gave a false impression of Twinkle’s standing in market terms. Her second 45, “Golden Lights,” an understated melodrama of love corrupted by fame, reached the edge of the Top Twenty, and later releases entered overseas charts. Moreover, “Terry” had bubbled under the US Hot 100. Further progress, however, was thwarted by US immigration authorities who temporarily refused visas to UK pop entertainers in an attempt to stem the ‘British Invasion’. Among those advantaged by the sanction were New York’s Shangri-Las whose “Leader of the Pack” in early 1965 shared a similar scenario to “Terry.”

Nevertheless, Twinkle’s early retirement as an entertainer was imminent: “I was on a particularly unnerving spell of one-nighters, and Hamburg was the first place I ever went to without an escort. I went on at the Star-Club with a pick-up group, and it was a nightmare—mainly because I thought I’d only have to do one set. I did several, doing the same numbers and wearing the same stage outfit. I gave up performing then and there—at the age of 17.”

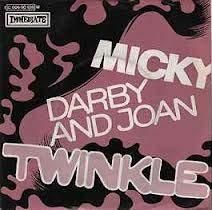

Her sporadic latter-day offerings, however, were rich with intrigue. An approach by former Rolling Stones svengali Andrew Loog Oldham in 1969 resulted in the issue of ebullient “Micky” on a subsidiary of his ebbing Immediate label. A eulogy to her then-boyfriend, Michael Hannah, it was produced by Manfred Mann’s Mike d’Abo.

The next few years were spent as a house songwriter for ATV Music. This period embraced too the oddest tangent in her career when she and her father amalgamated as ‘Bill and Coo’ for “Smoochy Smoochy,” a single considered worthy of a slot on an early evening television magazine programme; its interest lying less in Twinkle’s pseudonymous re-emergence than Sidney’s post as joint deputy leader of the Tory opposition on the GLC.

More credibly, Twinkle made a serious attempt at cracking the album market during the mid-1970s fad for singer-songwriters. Boldly, she tested the water with two quite prestigious concerts of new material, accompanied only by a pianist: “I didn’t need the money but I wanted to show people that I wasn’t just a one-hit wonder.” Warm reaction from both the audiences and other artists such as Colin Blunstone and Cat Stevens indicated that she was well-placed to become, perhaps, a UK ‘answer’ to Carole King. Indeed, a concept album to tie-in with a film based on Hannah’s life was completed when its subject was killed in 1974’s Paris Air Show disaster, and “I felt too personally involved to see it come out.” All that surfaced then was a promotional single, “Days.”

Once again, Twinkle withdrew to the back corridors of pop. Still an avid surveyor of the hit parade, however, she gained a commission from EMI Music to turn out a specific number of compositions per year. These would be put in the way of suitable vocalists. It was, she admits, “a privileged position but I blew it mostly through lack of confidence. I think I became a tax loss.”

She signed off with a disinclined 1982 revival of the Monkees’ “I’m A Believer,” by which time, music had became a sideline to marriage (to the distinguished actor Graham Rogers, known most conspicuously as star of ITV’s Cadbury’s Milk Tray commercial), motherhood and a hands-on commitment to animal welfare—with the writing of children’s stories her principal creative pursuit.

As the decade turned, Twinkle thought aloud about treading the boards again: “I went to see two old friends, Billy J. Kramer and Frank Allen of the Searchers perform in Croydon. The venue—a theatre rather than some dingy dive—and the audience’s enthusiasm were inviting enough to erase flashbacks of how ghastly it had been in the old days.”

A cog in the vehicle of her brief but well-received comeback as a grande dame of the Swinging Sixties nostalgia circuit, I was bass guitarist and self-appointed leader of her backing combo drawn, from Screaming Lord Sutch’s Savages and my own Clayson & the Argonauts. However, before the start of her first tour in this capacity, we were superseded by The Four Pennies. There were also episodes such as her official opening of the Cavern—nothing to do with Liverpool, but a restaurant club in rural Essex. After Twinkle cut the ribbon, the evening was soundtracked by a local 1960s tribute group—with whom she sang “Terry” in a voice that had lost little of its adolescent purity. Into the bargain, she had also clung onto much of her blonde allure.

Neither was a return to at least a qualified contemporary prominence out of the question. Reissues of “Terry” had spread themselves thinly enough to sell well without cracking the Top 50, as did a compilation album with sleeve notes by Bob Stanley of 1990s chart contenders St Etienne. Of greater import had been a version of “Golden Lights” as a 1986 B-side by the Smiths, whose practical approbation had already brought Sandie Shaw back to the Top 30 after a fifteen year absence. “Nobody’s ever heard the decent stuff I’ve written,” sighed Twinkle, “Also, after ‘Golden Lights’, nothing I have ever done has been to my liking. I’m not qualified to do it alone, but I wish I was because I know exactly what I want—but somebody else has to interpret that for me, especially with today’s equipment.”