-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

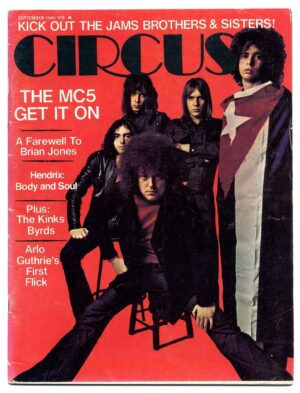

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—just months after the passings of guitarist Wayne Kramer on February 2 and one-time MC5 manager John Sinclair on April 2.

Thompson left this world in a much quieter setting—the serenity of the MediLodge recovery facility in Taylor, Michigan—than where he made his name some 17 miles away, the legendary Grande Ballroom in Detroit. You couldn’t think of one without the other: The Grande was where the MC5 were the house band, and the MC5 put the venue on the map in the late ’60s with electrified performances pushing the bounds of music, volume, culture and even politics; plus they recorded their first album, Kick Out the Jams, there in 1968.

You also couldn’t think about many musical developments since that pivotal debut without thinking of the MC5—not just their often-mentioned influence on punk rock, but on strains of hard rock and heavy metal, not to mention myriad Michigan contemporaries. Without the MC5, there probably wouldn’t have been a Stooges and definitely wouldn’t have been the Up, Third Power might not have evolved from psych into Detroit-infused hard rock, and Brownsville Station might not have cranked the amps to 11 in their quest to bring a ’50s rock ’n’ roll sensibility to the ’70s. Think about the impact of one of those bands, the Stooges, then try to imagine a world without them. Or maybe, as vocalist Rob Tyner proposed in the inner gatefold of 1971’s High Time swan song, “Think of a world where art is the only motivation.”

The MC5 thought big, and even hit #30 with the debut album in 1969, but it was their art that endured, not fame or record sales. Musical or otherwise, the Five’s radical art laid the groundwork for much that followed—providing listeners with a guidepost to escape the confines of societal conformity. While they weren’t peace-and-love hippies playing to oil-projected light shows, the MC5 were very much in line with the counterculture, even—as part of their involvement in the White Panther Party’s “total assault on the culture”—aligning with the Black Panthers’ 10-point program and a musical parallel to civil rights, free jazz.

As history has liberated wheat from chaff, many forget what the ’60s were really like and how much the MC5 stood out. The enduring images of the ’60s are of long hair, beads, flower power, Vietnam protests, Haight-Ashbury and Woodstock. But for a microcosm of what the dominant culture really was, look at any given 1960s high school yearbook and you’ll see boys with ultra-short hair donning formal wear in almost every picture, girls decked out in frilly dresses and noticeably absent from the sports pages in those dire pre-Title IX days, and every student looking much older and virtually indistinguishable from most teachers and administrators as a result of the sartorial requirements.

Fashions had changed by the ’80s, but not social norms. If you came of age in the suburbs, you probably lived comfortably, but your life was boring—filled with fast food, cable TV, chainstore malls, concrete embankments, manicured lawns, boxy station wagons and idiotic neighbors competing over who had the latest gizmo or gadget. Inspiration also couldn’t be found on the radio, which was infested with noxious AOR, new wave and some of the wimpiest pop ever conceived. Basically, the ’80s was a repudiation of the ’60s: antiwar sensibilities replaced by Rambo-like “war is fun” nonsense on the silver screen, musical creativity harnessed and stifled by corporate commercialism, and a pushback on civil rights and women’s rights that (sadly) carries on to this day thanks to right-wing apparatchiks trying to undermine both. And did I mention that the ’80s were really boring?

For some, the escape hatch was punk rock, a genre that owed a lot to the MC5; for others, it was heavy metal. Or maybe if you were getting bored with both like me, it was the MC5. With two of their three albums long out of print and the first uncommon in spite of an early ’80s Elektra reissue, they were inaccessible, buried and forgotten—which made them even more of a revelation when you finally heard them. Kick Out the Jams was raw and incendiary, Back in the USA was streamlined and terse, and High Time was a poetic monolith that should have been a breakthrough, but they were all great in their own way—evoking concepts, imagery and worlds alien to ’80s conformity. The same thing that spoke to musicians spoke to me as well, even if by that point all five members were living in relative obscurity.

Two of the MC5, Tyner and guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, died in 1991 and 1994, respectively—right on the cusp of the band going from cult underground phenomenon to elder statesman. CD reissues of all three albums proper in 1991 and 1992 hastened that higher profile, as did several albums worth of previously unreleased material that same decade, and by the 2000s survivors Kramer, Thompson and bassist Michael Davis were able to parlay that newfound (if minor) recognition into the DKT-MC5 with various side men—a project that ended with Davis’ death in 2012.

The legacy won’t end now that all five are gone. Heck, even the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame finally recognized them in its musical excellence category this year. As long as there are musicians with a rebellious streak or people who simply want to hear high-energy rock ’n’ roll, the MC5 will live on. Neither will be in short supply anytime soon—if ever.