-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

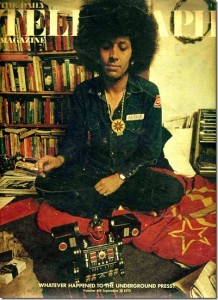

Memories of Mick Farren

Musician, sound-hound and writer, Michael Anthony ‘Mick’ Farren (September 3, 1943 – July 27, 2013), was part of the Brit art school lot of the ’60s. Farren initially had a master plan laid to be graphic designer for the Sunday news supplement, and ended up being one of the most iconoclastic, outspoken and prolific voices of his generation. Retrospective theory hails Jim Morrison as punk godfather, but the Deviants with Mick at the mic were the manifestations of those theories in-the-day, balancing beauty and brutality with their pulsing, sinister mind-fucked mutant blues and torrents of visceral, explosive noise. The Deviants reflected the innovations of under-heroes stateside and a few years prior some of their fellow travelers, yet for all the deconstructionist tendencies of the group (much like Mick the mouthpiece in his solo work) their center always remained grounded in the shake of first-gen rock’n’roll.

Always a vocal proponent of the undying spirit of underground musical rebellion, Mick’s The Titanic Sails at Dawn for NME (a must-read) both saluted the burgeoning UK punk scene and inspired fumbling noise-makers with its call to action zeal, many liberally snorting up the vapor trails of moves made with the Deviants in the late ’60s. The movement also revitalized Farren’s personal musical output after a near decade absence, with little changed in his approach than a bit of added vigor. UFO Club doorman, de facto leader of the UK chapter of the White Panthers and gonzo/rock writ figure non-pareil, he touched the lives of countless individuals. Let’s hope Mick gives the Grand Slumlord the same stick given to society at large over the years. Colleagues and confidants Dan Epstein and Bomp’s Suzy Shaw reflect on their friend below.

(Jeremy Cargill)

During his nearly 70 years on this planet, Mick Farren wore many hats, and all of them at a jaunty and rakish angle. (Metaphorically speaking, of course – as if any chapeau could have perched for long on that fabulous Farren ‘fro!) Rocker, poet, journalist, critic, promoter, activist, raconteur, radical shit-stirrer, author of everything from vampire and science fiction novels to treatises on Elvis, Jim Morrison, amphetamines and conspiracy theories – the man was utterly impossible to pigeonhole. If you loved all of what he did or some of it or none of it, it didn’t matter; he was still going to keep right on digging away in whatever direction his impressive intellect and indefatigable curiosity took him. While it’s tempting to call a gent of such breadth and depth a “Renaissance Man,” that expression reeks too much of shallow dilettantism these days to apply here. Basically, he was Mick Fucking Farren, full-on, full-time and full-stop.

I will leave it to someone else to offer up a full appraisal of Mick’s musical and literary contributions-not because they weren’t significant (they were), but because in my sorrow over the news of his death, all I can think about is the person I knew, as opposed to his discography or bibliography. His death is a shock to everyone, especially his family. I’m thinking about how hard it might be on them, as I’m not sure if he left a will behind, which means his estate might have to go through a probate process, which might take months, if not years to resolve. But I won’t go into all of the personal stuff now. What matters is that his songs clearly meant a lot to a whole generation of people. Those, thankfully, will live on; but the warm, brilliant, hilarious man that I was honored to call a friend and colleague for nearly twenty years is gone forever, and that breaks my heart.

I first met Mick in early 1994, when he signed on as a regular columnist for the LA Reader, where I was employed as an assistant editor. I was 28, just belatedly getting my journalism career in gear, and completely starstruck by the notion that my name was to be on the same masthead as the Mick Farren, the legendary writer whose stuff I’d read in Trouser Press (and back-issues of the New Musical Express) as a music-crazed teen. The first couple of times he showed up in the office, filling up the hallway with his imposing, leather-overcoated frame and rolling, piratical gait, I was too far intimidated to introduce myself. But somehow the ice was eventually broken, whereupon I quickly surmised that he was as much of a teddy bear as he was a buccaneer, and a man always relished a good chat – even with an aspiring writer who was perhaps unhealthily obsessed with late-60s British rock and psychedelia. Mick, bless him, was incredibly patient with my endless variations on the question, “What was the London music scene like in 1967?” But he seemed to have little interest in discussing his own music, unless it was something he was currently working on. Early on in our acquaintance, I showed him the passage on the Deviants in Vernon Joynson’s The Acid Trip: A Complete Guide to Psychedelic Music, which described 1968’s Disposable LP as partly that, and their self-titled 1969 album as “disappointing.” I was hoping to get a ripping rant from him in defense of all things Deviants, but no such luck. “I’d say that’s a pretty fair assessment,” he shrugged, and left it at that.

On the other hand, getting him to talk about other artists was easy, and great fun; in retrospect, I wish I’d had a tape recorder running, but in my head I can still hear him raving about what an amazing live band The Move were, or complaining about how Tomorrow would “play this bloody endless version of ‘Why’ by The Byrds, which would always fall apart when Twink and Junior started disrobing,” or recalling how sick he and his mates were of hearing The Who play their mini-opera “A Quick One (While He’s Away),” but how blown away they all were when “I Can See For Miles” came out. And, of course, there was the infamous story about him luring the MC5 to the UK to play the Phun City festival, only to break the news to Wayne Kramer and Co. upon arrival that there was no money to pay them with…

There were also salty tales from his days as a music journalist, my favorite being the one where he interviewed Marianne Faithfull in an office at Island Records. “How are you at picking locks?” Marianne asked him, shortly after the Island publicist left them alone. “Not bad,” he replied. “Well, that’s Chris Blackwell’s liquor cabinet over there,” she said. Mick successfully popped the lock, and the two proceeded to enjoy a most convivial chat fueled by some of the Island owner’s top-shelf booze.

I could have listened to this kind of stuff for hours and often did, whether it was loitering in the Reader hallway or (once we became friends) lingering over drinks at Formosa or some other Hollywood watering hole. It was also almost ridiculously easy to get Mick riled up about acts and artists he didn’t like – I sometimes used to drop Scott Walker into our conversations, just so I could hear him sputter with rage. There was something wonderfully cartoon-like about the way Mick’s voice would jump an octave whenever he’d get worked up in enthusiasm or anger, and my fellow Ugly Things contributor Eric Colin Reidelberger (who also worked at the Reader for a time) and I used to amuse ourselves endlessly by imitating him in “high dudgeon” mode. In fact, Mick once busted us in my office while we were in the midst of doing our dueling Mick Farrens. “I don’t actually sound like that,” he huffed, glaring at us over the top of his spectacles like a cross schoolmaster, and of course sounding exactly “like that”. But he could give just as good as he got: One night when several of us Reader staffers were out for a drink, someone asked him what he thought of his countrymen electing Tony Blair as their prime minister. “That would be like electing Dan president,” he replied.

Still, when we weren’t poking fun at each other, Mick was incredibly complimentary and encouraging about my writing – an unbelievable shot in the arm, considering that he was (and remains) one of my all-time favorite music journalists -and he was a real pleasure to work with on the rare occasions that I edited his Reader copy. There were writers at the paper who would chew your head off if you so much dared to alter a word of their brilliance; Mick, on the other hand, wanted his editors to push him and spar with him. The hell of it was, his stuff was so good right out of the chute, there was usually little point in sending any of it back for a re-write. Mostly, though, editing Mick’s submissions fell to others, and I saw his copy for the first time when it was published; invariably, it was the first thing I turned to when I picked up a new issue. And whether he was writing about the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, the O.J. Simpson trial (his likening of OJ’s visage to an Easter Island moai still makes me chuckle to this day) or Tom Jones’ latest attempt to break into the US charts, it was always fiercely intelligent, deeply funny and profoundly thought-provoking. His lefty ex-pat Brit voice was an odd fit in a paper that was aggressively trying to market itself to West Side yuppies, but (as one of my former colleagues recently observed) it also lent the Reader more credibility (and depth) than it probably deserved.

Mick was extremely active on the LA music scene in the mid-90s, and-next to the Baby Lemonade version of Arthur Lee and Love-I probably saw him perform more than any other local act during that time. I was initially hoping to hear old Deviants songs or solo material like “Let’s Loot The Supermarket Again…,” but Mick had completely different sorts of fish to fry. Backed by a revolving cast of musicians that usually included ex-Blodwyn Pig saxophonist/flautist Jack Lancaster (for whatever reason, Mick refused to acknowledge that Jack had ever been in “the Pig,” and used to get stroppy about me mentioning that factoid in the Reader gig listings), guitarist Andy Colquhoun, and sometimes Wayne Kramer, Brad Dourif and Ric “Mick Shrimpton” Parnell, Mick would hector and regale us with epic poems like “Disgruntled Employee,” “Atomic Boogie Hour” and “Memphis Psychosis” over a firestorm of angular free jazz. It was uncompromising, it was uproariously funny, and it was unmistakably Mick.

Mick was equally uncompromising in his approach to life. In a way, I’m rather surprised that Mick lived as long as he did; I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who actively took worse care of himself. If it were anybody else, they would have crumbled at half the things he did; then again, not everyone can be Mick. The man’s alcohol intake was prodigious, ditto for tobacco (despite a lifelong struggle with asthma). Yet, he never considered rehab or even looked at centers like Arista Recovery-he didn’t believe that he needed ‘help’. He lived how he wanted and didn’t give two cents to what people thought of him. He rarely did anything that remotely resembled exercise, and boy did he love his desserts – though he often used the post-war rationing of his childhood as justification for his unquenchable adult appetite for sugar. (“We couldn’t have sweets, you know.”)

Mick and I lived near each other, so I had to drive him home many times after he’d gotten completely legless at one Reader function or another, though just about every member of the paper’s editorial staff was similarly pressed into duty at least once. My all-time favorite “driving Mick home” story is the one from the paper’s office Christmas party of 1995: Despite a pitifully stingy refreshment spread-at the time, the Reader was about eight months away from going under-Mick still somehow managed to get righteously, rip-roaring drunk. James Vowell, the Reader‘s publisher, saw Mick swaying unsteadily in the reception foyer and asked me to take him home. “C’mon, Mick,” I said, “Time to go.” Mick wordlessly grunted his assent, then paused for a moment and reached back to grab a full bottle of Myers’s dark rum from the drinks table; as James looked on with a deeply appalled expression, Mick tucked the bottle inside his coat and he staggered out the door. I was never able to figure out if he thought he was being slick and no one saw him do it, or if this was his way of saying, “Fuck you, James-you’re paying us all shit, so I’m hereby extracting my Christmas bonus!” When I asked Mick about it the next day, he claimed to have no memory of the incident, or any knowledge of the bottle’s whereabouts.

Mick and I saw each other much less after the Reader closed, though we still stayed in touch on and off over the years, even after he moved back to the UK. “It’s easier to be poor in England,” he said, and certainly it was easier there to afford health care for his many afflictions. But I also got the sense that the return to his homeland revitalized him creatively and spiritually. In the summer of 2011, I contacted Mick about writing something for “Single Notes,” a music-related eBook project I was helming for Rhino. We hadn’t spoken in a while, and he caught me up thusly:

Dan – It’s really good to hear from you. England is really interesting. Tories in power, economy in the toilet, riots in the streets, and last night North London was burning after the cops in Tottenham shot a well known local dealer. Oh boy. But I do have healthcare, a pension, a very nice apartment and my cat from Hollywood. (Which was an epic in veterinarian bureaucracy by itself.) I’m also being treated like a famed and venerable pirate back from the rock & roll seven seas — which I greatly enjoy. And the Deviants are back in business. We just played Glastonbury. (Mud to rival WWI.)

Almost two years to the date of that email, Mick collapsed onstage while he and the Deviants were playing the Atomic Sunshine Festival at London’s Borderline nightclub. While his passing is indeed sad and tragic and leaves a massive, unfillable crater in the lives of so many of us, we can at least be comforted by the thought that he died doing what he loved, surrounded by people who adored him and admired his work. None of Mick’s rock & roll heroes enjoyed an end as fitting as his own; in that respect, at least, you could certainly say that Mick beat the odds. To paraphrase the Righteous Brothers, if there’s a rock & roll heaven, you know they’ve got a helluva bar – and you know that Mick is propped against it as we speak, holding court and entertaining the likes of Gene Vincent, Jim Morrison and Sun Ra with one outrageous tale after another.

Speaking of his work: Mick’s Single Notes eBook, Elvis, Esquerita & The Zenomorphs: The Music Of The Monkey Planet, is currently scheduled for an August 29 release. It’s a riotously Farren-esque piece of speculative fiction – “Multidimensional alien anthropologists study rock & roll as planetary species behavior,” was how he initially pitched it to me – and it was a total joy and privilege to be his editor on the project. While it saddens me terribly that Mick didn’t live to see its publication, it also gladdens my heart that his many fans will get to enjoy one more blast of brilliance from one of the great brains of our time.

Here’s to ya, my friend. Thanks for everything.

(Dan Epstein)

I’m sure by now you’ve all heard the news about the death of our friend Mick Farren. I wanted to write a little tribute to him and show a more personal side of a truly wonderful man. If you don’t know a lot about his work just google, there are stories about him in nearly every paper in the world. He was one of a kind. We heard the news yesterday, but somehow it takes a while to really sink in, that we won’t see our friend again.

Mick and I had known each other for years, but became really good friends when Patrick made the brilliant decision to ask him to edit the Bomp book (Bomp!: Saving the World One Record at a Time, Ammo Books, 2007). He was the perfect person for the job and loved the project. As a result of the book Mick and I worked side by side for over a year, culling articles from the zines, picking out photos and fact checking. In addition to that he decided that I needed to write some personal stories about life at Bomp. I initially declined, not really wanting to be in the spotlight, but he insisted. I relented and told him I’d write up something rough and he could edit it, but when I sent him the story he loved it just as I had written it and made me write 7 more! That brought us into a very close relationship. We ended up having a great time together telling the stories about the early days of Bomp, although I declined to include some of the more scandalous tales. He told me, with his eyes twinkling, “There’s another book there, darling, an even BETTER book!” We didn’t get around to that one, although he would have loved it if I had let him do it.

He always had projects going, one of which was a book of cat stories. Some might find that surprising, but Mick wasn’t all vampires and rock’n’roll, he loved animals and we would often send each other pictures of our cats or cute things he found on YouTube . He sent me some very good stories from his proposed cat book to see what I thought, and they were amazing, sweet, funny and insightful. Fortunately I printed them out and saved them, as there is no trace of them on my computer. I suppose that book will never be published, at the time he had other books that he was working on and put that one on the back burner. I hope somebody else has the stories as well and will see to it that they are available in some form.

Doctor Mick even saved me from unnecessary surgery! I had gone to the doctor for a regular checkup and got the extremely surprising news that my blood test results had shown that my kidneys were failing and they needed to schedule a biopsy; that it could be cancer. Needless to say, I was in a dead panic, absolutely hysterical. I’d never even had a cavity, let alone kidney failure, and seemed to be in radiant health by all accounts. I called Mick, sobbing, and he listened quietly until I finished my story and said, taking a slow drag off his cigarette , “Darling, don’t be ridiculous, you are entirely ROBUST, merely call this stupid doctor and tell him you demand a second test!” I swear it never would have crossed my mind to question the doctor, but thanks to Mick, I did just what he said and avoided a very unpleasant month. Mick was right, nothing wrong with me all. We both had a good laugh later about the great health care system in America, and Dr Mick comes with me in spirit on all my doctor visits now, telling me to ask questions and not be so damned polite.

Mick himself used an Armenian pharmacist as his doctor, unable to afford health care here and relying on the pharmacist to supply him with the drugs he needed to breathe and remain ambulatory. He had emphysema and he had trouble breathing or even getting around. But he carried on as though nothing was wrong, and never quit smoking as far as I know. When we would go to pick him up at his apartment we wouldn’t worry about remembering the apartment number, you could just follow the smoke that hit you in the face the minute the elevator opened on his floor. When he would open his apartment door the smoke would practically billow out into the hall, I would worry about the cat and Patrick and I couldn’t really stay more than a minute or two without coughing, but Mick was steadfast, he was going to do things his way. I might remember we had breakfast one day, and he might have mentioned that the doctor from a reputed healthcare center (similar to Cardiovascular Group) told him his cholesterol was insanely high and that he may have to change his diet. He was cheerfully munching away on his usual bacon and eggs, (and beer, as I recall) and seemed surprised when I told him bacon and eggs was perhaps not the most “heart healthy” breakfast. He had never thought twice about what he ate, I don’t think he had a vegetable in his whole life and was rather stunned by the news about his breakfast. He remarked that perhaps the best thing to do was never go to the doctor and continued with his breakfast. He shortly thereafter moved to England, unable to afford even the medication from the pharmacist, and our regular lunches were, sadly, no more.

One of the tributes to Mick I just read said that he “died with his boots on,” and this is true is more ways than one. One of the things I would scold him about was his insistence on wearing high-heeled cowboy boots, perhaps necessary for public appearances, but he could barely walk as it was, and he seemed in constant danger of toppling over. I would beg him to “just wear some f*cking tennis shoes for god’s sake!” but he refused to do any such thing, he had to be Mick Farren and Mick Farren doesn’t wear tennis shoes.

The only consolation is indeed that he died doing what he loved, I just wish it had been 30 years from now. He was family to us; we’ll miss him every day.

(Suzy Shaw)

CSM remembrance: www.charlesshaarmurray.com/2013/07/mick-farren

Nat Nichols remembrance: www.hipspinster.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/dr-crow.html?m=1

The Titanic Sails at Dawn: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/jul/31/mick-farren-nme-rock-titanic-sails

Special thanks to Dan Epstein, Steve “Plastic Crimewave” Krakow, Eric Colin Reidelberger and Patrick Boissel for assistance with the playlist.

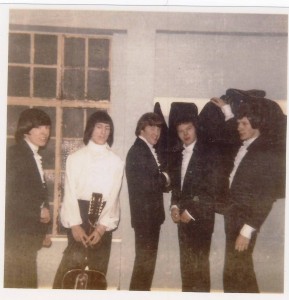

George Gallacher – 1943-2012

It is with deep sorrow and incredible sadness that we learned of the death of our dear friend George Gallacher, lead vocalist and founder member of the Poets, who died suddenly from a heart attack while driving home from watching his favorite football team, Partick Thistle, on Saturday August 25, 2012. On the day “The Jags”, as Thistle are known by their fans, won 3-0 against Dumbarton at their home ground Firhill, in Glasgow, so George would’ve been pretty ecstatic. He was such an avid supporter that, unusually, the club held a half-time tribute to him on the day of his funeral, playing Poets songs, while former Scotland player Alan Rough read out tributes.

George was born in the Garngad (later Royston) area of Glasgow and would’ve celebrated his sixty-ninth birthday on 21 October.

In 1964, The Poets were quickly signed to Decca by Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, who produced for them a brace of highly-innovative singles, all co-written by Gallacher, and guitarists Hume Paton and Tony Myles. Forever etched in the minds of beat fans is the group’s scorching February 1965 single, “That’s The Way It’s Got To Be,” and its sublime, truly haunting counterpart, “I’ll Cry With The Moon.” This showcased both the tough and romantic sides of the young Gallacher’s talent, across intense, creative, and thoroughly mesmerizing material. The weird baroque-beat stomp of “Now We’re Thru,” their debut from late the previous year, would give them their only Top 30 placing. The Poets followed manager Oldham into his new Immediate label venture, cutting two singles there including the spellbinding “Some Things I Can’t Forget,” the group’s preferred choice for the topside. This was over-ruled by ALO in favor of “Call Again”—“depressing stuff… and we were depressed that it was going to be our single,” recalled Gallacher in 2011.

In early ’66 after “Baby Don’t You Do It,” Gallacher left the Poets, disillusioned by lack of direction and momentum within the group, and the mess of ongoing management wrangles. He stayed in London until the end of the ‘60s singing back-up on sessions for such as Keith Relf and Spencer Davis, doing A&R work, writing and recording for labels including United Artists, Fontana and Major Minor. Gallacher also taped some excellent songs of his own with backing by the pre-White Trash group, the Pathfinders, who included former Poets guitarist (and by then Gallacher’s brother-in-law) Fraser Watson. At least four titles exist on acetate only including “The Tailor,” “A Weathercock’s View Of Life,” and the more well-known “Dawn (A Portrait).” A little-known fact, however, is that in 1968 Gallacher also supplied lead vocals for an album project by a group called the Illusive Dream which remains unreleased to this day.

When George returned to Glasgow, married with children, much of his free time was spent playing junior league football. As early as 1963, before the Poets broke out, George’s prowess on the football park had already been noted and he signed up for trials with Leicester City’s youth team alongside England’s future goalkeeping hero Gordon Banks.

But music was in Gallacher’s soul, and after a brief stint playing with old pal Alex Harvey, he and Watson formed the hard rocking, politically aware Dead Loss Band, also the Dansettes, The Blues Poets and, more recently, the Nearly Men. His friend, award-winning author James Kelman, had also cast him as the leading role in his acclaimed 1994 play One Two Hey!, the story of a struggling blues group, mirroring that of the Poets.

Gallacher also returned to education, gaining degrees in both English and Philosophy at the University of Strathclyde, before becoming a teacher, and mentoring to asylum seekers, many from war-torn Kosovo.

A unique vocalist until the very end, George was blessed with a thoroughly commanding stage presence, as evidenced by those in attendance at recent concerts given by the reconstituted Poets line-up where George and Fraser were backed by longtime friends and fans, the Thanes, in Glasgow, London, and at what would turn out to be their last ever appearance, at Festival Beat in Italy on 30 June, playing almost all of the group’s ‘60s repertoire before jubilant, receptive audiences.

On a very personal note, as one of George’s and his family’s friends for the last twenty five years, I’d like to say that life has been richer by far having known him. George Gallacher was a very generous, gracious, wryly funny, heart-thinking individual, an extraordinary spirit with an astonishing musical gift. He will be dearly missed by all who knew him. He journeys on leaving behind his dear wife Anne, and their two sons, Craig and Fraser. RIP George, you were some man. (Lenny Helsing)

Eddie Bertrand 1945-2012

Surf guitar pioneer Eddie Bertrand has passed away from cancer at the age of 67. Bertrand formed the Belairs with his high school classmate Paul Johnson in 196o, going on to unleash the classic “Mr. Moto” and several other excellent surf instrumentals. He left the Belairs in pursuit of a harder-edged sound, which he found with Eddie & the Showmen, a popular live attraction in the surf-crazy South Bay area of his native Southern California. His heavily picked, driving leads during the Showmen era revealed a big Dick Dale influence. Eddie Bertrand’s special brand of guitar artistry puts him in the top echelon of surf guitarists and his recordings deserve an exalted place in any music collection. (Dave Gnerre)