-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

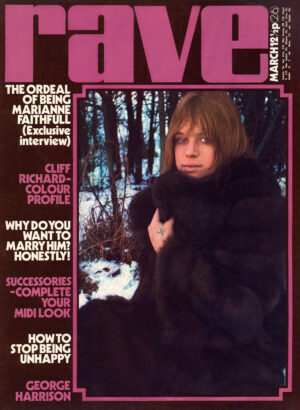

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

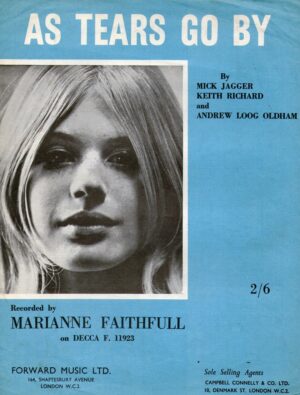

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1963-1967 record producer and manager of the Rolling Stones, for Discoveries magazine. “The fact is forgotten that Marianne had, between August of ‘64 and the summer of ‘65 four Top Ten hits in the UK. ‘As Tears Go By’ and ‘Come And Stay With Me’ held up.”

“As Tears Go By” is a song penned by Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Andrew Loog Oldham. It reached a top ten position in the UK singles chart. The Stones then recorded their own version, included on the American pressing of December’s Children (And Everybody’s) in 1965. Their American record label London issued “As Tears Go By” as a single that landed in the number six spot on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

It was Marianne who gave Mick the book which inspired the song “Sympathy for the Devil.” In the 2012 Rolling Stones documentary, Crossfire Hurricane, Jagger acknowledged his influence for the composition was informed from French poet Pierre Baudelaire and the Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita. An English translation was made available in 1967. The song is heard on Beggars Banquet, produced by Jimmy Miller and engineered by Glyn Johns and Eddie Kramer in London at Olympic Sound Studios. Marianne is one of the backing vocalists on the recording.

Marianne went on to record more than twenty solo records, including the acclaimed 1979 album Broken English, and 2018’s Negative Capability, which included collaborations with Keith Richards and Nick Cave.

In the early ’90s Marianne was made a professor by Allen Ginsberg at the Naropa Poetry Institute in Colorado, where she has taught lyric writing. Her certificate reads: Marianne Faithfull, Professor Of Poetics, Jack Kerouac School Of Disembodied Poets.

During 1994, Marianne Faithfull had a new album out, A Secret Life, a collaboration with producer/arranger /co-writer Angelo Badalamenti (best known for his working relationship with filmmaker David Lynch, including orchestrating the music for Twin Peaks). Island Records at the time also released Faithfull: A Collection Of Her Best Recordings, and in 1994, Little Brown published her candid terrific memoir, with David Dalton, Faithfull: An Autobiography.

It was Allen Ginsberg, who encouraged me to look Marianne Faithfull up the next time she was in Hollywood. I was given an interview assignment for HITS magazine. Marianne’s publicist at Island Records arranged for me to visit her on Sunset Boulevard at the Chateau Marmont.

So in 1995 I knocked on the door to Marianne’s hotel room at the Chateau Marmont, ironically, right next to the suite where years earlier I had interviewed and had lunch with Leonard Cohen.

Marianne answered my knuckles, “Welcome to the poet’s corner,” she beamed.

I looked at her for about thirty seconds. She had big green eyes. Clad in black. Not punk black, but black blouse, black pants and black nylons. Marianne was an image out of Hollywood’s Jazz City music club circa 1958, a cinema noir sister of Susan Oliver and Gloria Grahame. She wore no makeup, blonde, long hair, a little shorter in person that I expected. She had a dancer’s body. In fact, twice during the two-hour chat, she leaped off the couch onto the rug and sort of did a move, an interpretation of “the sideways pony” dance that Tina Turner once taught Mick Jagger in the hall way in front of her in 1965 at Colston Hall in Bristol, England. She told me her mother Eva taught her to dance as a child.

I then mentioned that I briefly danced on American Bandstand as a teenager in May of 1966.

She was rather impressed.

“Whew…Remind me to give you a kiss and a hug when you leave today and don’t worry if my boobs get in the way,” she comically warned. “No problem,” I assured her.

oom service delivered Marlboro Lights. Marianne also ordered a vodka martini for our smoky conversation. I had a mineral water. The record label paid.

Marianne was very supportive to me when I complained about not getting a book deal. A decade later she had a chapter in my first book This is Rebel Music, published in 2004.

This still alluring Marianne Faithfull turned out to be a fascinating interview subject and a real yenta. She was a lot of fun and never avoided a question during our time together.

I got from your autobiography you were a poetry head.

Always. That’s one of the reasons I love Allen so much and William Burroughs.

Needless to say, one of the things that drew you to the music and word work of Bob Dylan. I noticed you were in one of the hotel room scenes in Dylan’s Dont Look Back film that chronicled his 1965 British tour. In your book in the Dylan Redux chapter, you provide a real cool glimpse of Dylan in action in the mid-60’s and then years later. I thought it was one of the sections where you and David Dalton worked really hard in bringing the moment to the reader.

I think that was the bit that David did best. I didn’t work the hardest on that, David did. But it was wonderful. I wish he’d written the whole book like that. And all the Bobby Neuwirth stuff was so beautiful.

Had you never seen a rock person like Dylan or an American like him in 1965?

Never. Never in my wildest dreams could have imagined anyone like Bob in 1965. His brain. But I was frightened. I didn’t know they were probably more scared of me. I don’t know. They were all on methedrine. He played me the album Bringing It All Back Home himself on his own. It was just amazing. And I worshipped him anyway. That was where I got very close to Allen Ginsberg ‘cause Allen was the only sort of person I could recognize as being somewhat like me.

I really enjoyed the passage in your book when Allen came to London with the Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti. They read at Queen Elizabeth Hall. You had spent some time with Ginsberg during Dylan’s Dont Look Back tour and I laughed out loud as you described inviting Allen to the house you shared with Mick Jagger. Great image and a very fortunate position for you as Ginsberg sat on your bed with you and Mick naked under a fur cover.

As you put it, “Allen, as usual, was on a mission. Allen was trying to get Mick to put William Blake’s ‘The Grey Monk’ to music.” Again, until this book, I never knew you had such a jones for poetry, and beat generation poets.

(Smiles) I find them very sexy all those guys. Wonderful. I teased Allen in my book. I adore him. The first time I went to Naropa, Allen was literally by my side like he is. There was a lot of criticism and “Who is the woman?” “Why do you (Allen) think she can do this?” And he didn’t say anything. “I just do.” And then I came back again. We are very good friends. He also represents a lot of things for me that aren’t part of our friendship or our relationship. He is the greatest living American poet. I hooked Allen up with [producer] Hal Willner.

How did your autobiography come together? I know you’ve been approached over the years and obviously film adaptations are being offered on this book and your life.

It took a long time. I have great recall.

Why did you do the book?

I did it for you. (laughs). I did. I felt there was something in the story that was very common to everybody. I do believe that the details and the individuals are different, but the emotions and the sort of core thing are very, very connected to all human experience. Therefore, I felt it was a valid story to tell. And then again, I felt I was very close to some of the greatest people of my time. And I had a lot of help.

David Dalton came to Ireland for two weeks. He’s a very shy person. He selected me. Such a strange story. Tony Secunda – who recently died, I dedicated my paperback English edition to him – he had become a literary agent, and he was working with Dalton and he came to Ireland. I didn’t want to do this book, really. Much as I care for humanity…

And he picked David Dalton who was a big Rolling Stones fan.

That was peculiar for me. And my great tease. I would tell David at first, that what I saw in him as a writer was that he was basically a necrophilliac. “You have only written books about dead people. (James Dean, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison). How are you going to cope with someone who is not dead and not likely to be dead?”

And being a woman with opinions.

But David liked that.

But I’m sure you also gave a view and observations of your life and art process that were different than the myth and history events captured so far in the Rolling Stones documentation.

It took him a long time to believe me. I have to stand up for David because it wasn’t as simple as that. Yes, he was a Rolling Stones fan, but that in itself shouldn’t be a problem.

The interviews went on for hours.

And for once, you had the opportunity and forum to tell your side of the story. The truth you saw and experienced. You were in control.

Well I didn’t realize that, ya know. That’s what made it so hard for Dalton. He kept saying to me, “This is your book! This is your thing! I will only do what you want.” But I didn’t believe him.

Was it your intent in the book, and specifically this Dylan chapter to be so detail oriented about the environment? Obviously, you were doing a memoir. I know for a fact there are some scenes that went down that you could not invent unless you were there. And, I even feel it on the printed page.

Of course, I was there! I ended up adoring David. He’s one of my best friends now.

Did photos trigger recall of events?

No. I’ve been carrying this around for a long time. And I had remembered the things that were important to me which were always the same. It was always very, very clear that what I was really interested in and always had been interested in was motive and psychic position and why. There were a million things I could not remember, which are not interesting to me.

What was it like seeing the galleys? The first typeset manuscript?

That was heavy. (sighs). That was when I also saw the pictures. My editor came over with the pictures. That was one of the harder bits.

Did you take things out at that point?

Yes. It wasn’t legalities. There were some mistakes and I could not have them.

Was it hard during the interviews and the collaboration with David Dalton to tell your point of view? I would imagine you had to at times be combative.

Yes. I thought it was really good for me and about fuckin’ time I learned to do that. I didn’t want to. I resisted it but I had to. I had to. David is married to a very intelligent woman Coco and she really worked very closely with him and I think it had some impact. It was much harder work than David had ever done before. A living person.

In your book you mention some of the Rolling Stones characters in their songs came to life partially owing to acid.

Of course they did. I don’t think acid is relative or relevant anymore. I wouldn’t do it again. But I think that it was important then, and I think it taught us a lot.

They were all very much in love with me at that time. Not only me, but I was one of the many women they were in love with. Keith and I are still very close. I’m under his wing and I know I will always be under his wing.

Brian wasn’t as bad as everybody thinks. Well, Brian was a genius, but he was a very irritating person. Keith really loved Brian. I use Brian. I have a whole lot of friends on the other side that I call up when I need them. I use Brian, Janis and now I’ve got Tony Secunda and Denny Cordell.

I cut out some things about Brian Jones. He went on and on and made him much more of a worse person than he was. He could only do that really because he was dead. He couldn’t go on and on about Keith and Anita or even me because I did the classic Buddhist thing: I just did a drive all blames into one. I made that decision. That is something I learned from Allen. I’ve had good Naropa training. The galleys were hard to read.

What is it like looking and reading the book?

I’ve read it and re-read it and it’s still hard…It’s hard to believe I’ve done it and that it’s really me and a part of me now. David did a good job, man. I have to say this.

Your book is now out in paperback. I just got a copy. Do you have any more feelings on it since publication?

I’m terribly pleased with it and proud of it. It’s like a child of mine that has gone out and done well. It’s a good read.

As a teenager in England you went to a Catholic School St. Joseph’s in Reading. And devoured a lot of books and studied poetry. But in your autobiography, I learned you’re Jewish.

My dear little Piscean, my mother and my grandmother were Jewish. My mother came from a line of Austro-Hungarian aristocrats. My mother was a doctor’s daughter. She was a Jewess, those great Jews who went out and did it from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Doctors, writers, sort of like going into Oklahoma. Allen Ginsberg now is my Jewish Mother.

© 2025 Harvey Kubernik

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015’s Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016’s Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017’s 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His book Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll Television Moments) is scheduled for 2025 publication.

During 2006 Harvey spoke at the special hearings by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 Kubernik appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series).

Shel Talmy: August 11, 1937 – November 14, 2024

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My Generation” by the Who, and hit singles by the Easybeats, Manfred Mann, Chad & Jeremy, and worked with the Creation and Pentangle. He produced early sessions for a young David Bowie.

Talmy was raised in Chicago, and a graduate of Fairfax High School in West Hollywood. He later attended Los Angeles City College, before relocating to London in early 1963, where his A&R skills and recording endeavors changed our world.

I knew Shel for half a century and interviewed him numerous times. Our last encounter was in 2022 for a recording studio documentary. In November he emailed me touting the skills of pianist and arranger Tom Parker’s work on the Laurie Styver’s album Gemini Girl: The Complete Hush Recordings issued on High Moon Records.

Below are some excerpts from interviews I conducted with him this century.

Shel Talmy: I went to Fairfax High School and Los Angeles City College before I went to England in the early sixties. In Los Angeles and Hollywood for my sessions I insisted on being there for the mastering on everything I did. I started as an engineer with Phil Yeend. I spend a lot of time trying to perfect the sounds we were getting at Conway Studios. We spent time isolating instruments and working on drum sounds. Working on guitar sounds. In terms of days and hours. Microphone placements we did were utilized with the Who and Kinks.

Nik Venet gave me his demos when I first came to England that is what I used to talk my way into a gig at Decca. What I learned from Nik, bless his heart, was how to handle artists. He allowed me to come to Capitol while he was going stuff. I went to one of his Lou Rawls’ sessions. Lou and Sam Cooke were fuckin’ brilliant. I would hear how he would talk to artists and the engineers. And I have done that forever.

I returned the favor and I wrote to Nick and said there’s a band called the Beatles you really got to take a listen too. I think they are gonna be enormous. Never heard another word. Thirty years later I ran into Nik at a studio and he told me when he got my letter he ran into Alan Livingston’s office, the head of Capitol and badgered them into signing the Beatles. Nik signed the Beach Boys in 1962.

I brought with me from Conway a way to using the equipment of making everything louder apparently louder than it actually was. I did that with bringing up a guitar through channel one, which was right at the beginning of distortion and the other one which was normal. So, I used to bring up the distorted one underneath the good one and the entire level went up. And I always tried to do everything I could without distorting. So, I was always near the red line of the meter. I brought that with me. I liked hearing records that I think it actually expands the vocal audio range of what you’re hearing. As far as echo, Conway had a damn good echo chamber that Phil worked on and it was in a little closet. I like echo where it applies and I don’t like echo where it doesn’t apply. There’s a lot of stuff I think that sounds a hell of a lot better dry then it does with echo. I loved working with Chad & Jeremy. They were more folky and orchestrally-arranged. I loved working with the Pentangle.

The UK technical people didn’t think I was weird. They thought I was different because I was pretty much the first American producer there. The first place I went to was IBC on Phil’s recommendation. That’s where Phil worked. And, they were way ahead of everybody else. In terms of gear, they had young engineers who were willing to experiment. Glyn Johns. And then Olympic. Initially it made my life easier. Glyn Johns and Eddie Kramer, who I used twice. Gus Dudgeon was my assistant at Olympic with Keith Grant.

I always felt the song was seventy-five per cent of the record.

1967 and the Summer of Love? By NME or Melody Maker, I was record producer of the year. I thought Sgt. Pepper was brilliant. Psychedelic or not it had form as far as I was concerned. Maybe they went a little overboard with the psychedelic stuff. The songs were great. What they did was a little too long for me. If there was a great song that went five minutes, that’s cool. Even six, maybe at a stretch. But I still subscribe to the fact that if you’re gonna hear a great song you’re gonna pretty much know it in the first eight bars. And then it continues to develop, three to four minutes is about the right amount of time for it.

Ray Davies of the Kinks. How we used to work it, and at that point in time, was the most prolific songwriter I’ve ever known. He’d go home and bring you back a dozen songs the next day. What we used to do was sit down, in a studio, and he actually played piano, not guitar, and he’d play me the stuff. I heard four bars of “Sunny Afternoon” and I said, “That’s gonna make number one.” He ‘d play me songs. “That’s good … That’s not quite there yet. Let’s put that aside.” He went along with that. We never did demos. Sitting down and playing the stuff live.

“See My Friends.” Jon Mark was already influenced by Indian stuff, and I played a recording he did to Ray. And Ray came back the next day with “See My Friends.” We had to tune down the regular guitar and double-tracked it for a kind of sitar sound. It broke a lot of ground. We were so far, as you know of the market that it was the lowest chart record I ever had with the Kinks.

I have been saying for years that Dave Davies is probably the most underrated guitarist in rock ‘n’ roll. A damn good guitarist. He’s also a very good songwriter. He’s not as good as Ray, but then again, very few people are. Ray was in a class by himself. As was Pete Townshend. Lennon and McCartney. Dave was one small step beneath that in terms of how good he was. But he wrote some damn good stuff.

Contrasting Pete and Ray. The easy way in broad strokes… Is that Ray was the major social commentator of what was going on in England at that time. Pete was much more into early blues and what he could so with his guitar and loved sound. Of course, I encouraged all the power chords and all that kind of stuff and that’s what attracted me when I first heard them. I thought they were the first rock ‘n’ roll band I heard since I came to England. When I first arrived, I thought everything was incredibly polite. Pete and Ray, the only thing they really have in common is that both of them are really brilliant songwriters. I think it’s fair to say that Ray could not write a song that the Who would do and Pete could not write a song that the Kinks could do.

As a producer I knew they had global appeal.

Nicky Hopkins… With the Who and the Kinks. I found him real early. Nicky was one of my favorite people. A really nice guy. Easy to work with. A heavy-duty talented musician. I had him playing live with all these people, by the way. I didn’t bring him in for overdubs. I don’t know how to describe him. When you hear something that’s undefinable but you know it is brilliant. That’s what I saw with Nicky Hopkins. All the bands loved him that I introduced him too.

Pye Number 2 studio in the basement of ATV House, was the band studio and am guessing the dimensions about 20 X 30 to 40. Pye Number 1 was the orchestral studio and a lot bigger, never worked in it. Entering the studio, the control room was on the left, again guessing dimensions 10 X 15. We had Ampex tape machines, three-track and mono, and a little later, two-track. They had a good selection of mikes, Neumann, Telefunken, Shure, AKG etc, and I made use of a lot of them as I was miking drums with a dozen mikes. There was also a good B3 organ with Leslies that John Lord played for the first LP, and a good piano, I think a baby grand that Nicky Hopkins played on. The drum corner was near the control room and I had guitar and bass amps against the walls with baffles around them. This studio had really good acoustics and one of the reasons it was in constant use.

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—just months after the passings of guitarist Wayne Kramer on February 2 and one-time MC5 manager John Sinclair on April 2.

Thompson left this world in a much quieter setting—the serenity of the MediLodge recovery facility in Taylor, Michigan—than where he made his name some 17 miles away, the legendary Grande Ballroom in Detroit. You couldn’t think of one without the other: The Grande was where the MC5 were the house band, and the MC5 put the venue on the map in the late ’60s with electrified performances pushing the bounds of music, volume, culture and even politics; plus they recorded their first album, Kick Out the Jams, there in 1968.

You also couldn’t think about many musical developments since that pivotal debut without thinking of the MC5—not just their often-mentioned influence on punk rock, but on strains of hard rock and heavy metal, not to mention myriad Michigan contemporaries. Without the MC5, there probably wouldn’t have been a Stooges and definitely wouldn’t have been the Up, Third Power might not have evolved from psych into Detroit-infused hard rock, and Brownsville Station might not have cranked the amps to 11 in their quest to bring a ’50s rock ’n’ roll sensibility to the ’70s. Think about the impact of one of those bands, the Stooges, then try to imagine a world without them. Or maybe, as vocalist Rob Tyner proposed in the inner gatefold of 1971’s High Time swan song, “Think of a world where art is the only motivation.”

The MC5 thought big, and even hit #30 with the debut album in 1969, but it was their art that endured, not fame or record sales. Musical or otherwise, the Five’s radical art laid the groundwork for much that followed—providing listeners with a guidepost to escape the confines of societal conformity. While they weren’t peace-and-love hippies playing to oil-projected light shows, the MC5 were very much in line with the counterculture, even—as part of their involvement in the White Panther Party’s “total assault on the culture”—aligning with the Black Panthers’ 10-point program and a musical parallel to civil rights, free jazz.

As history has liberated wheat from chaff, many forget what the ’60s were really like and how much the MC5 stood out. The enduring images of the ’60s are of long hair, beads, flower power, Vietnam protests, Haight-Ashbury and Woodstock. But for a microcosm of what the dominant culture really was, look at any given 1960s high school yearbook and you’ll see boys with ultra-short hair donning formal wear in almost every picture, girls decked out in frilly dresses and noticeably absent from the sports pages in those dire pre-Title IX days, and every student looking much older and virtually indistinguishable from most teachers and administrators as a result of the sartorial requirements.

Fashions had changed by the ’80s, but not social norms. If you came of age in the suburbs, you probably lived comfortably, but your life was boring—filled with fast food, cable TV, chainstore malls, concrete embankments, manicured lawns, boxy station wagons and idiotic neighbors competing over who had the latest gizmo or gadget. Inspiration also couldn’t be found on the radio, which was infested with noxious AOR, new wave and some of the wimpiest pop ever conceived. Basically, the ’80s was a repudiation of the ’60s: antiwar sensibilities replaced by Rambo-like “war is fun” nonsense on the silver screen, musical creativity harnessed and stifled by corporate commercialism, and a pushback on civil rights and women’s rights that (sadly) carries on to this day thanks to right-wing apparatchiks trying to undermine both. And did I mention that the ’80s were really boring?

For some, the escape hatch was punk rock, a genre that owed a lot to the MC5; for others, it was heavy metal. Or maybe if you were getting bored with both like me, it was the MC5. With two of their three albums long out of print and the first uncommon in spite of an early ’80s Elektra reissue, they were inaccessible, buried and forgotten—which made them even more of a revelation when you finally heard them. Kick Out the Jams was raw and incendiary, Back in the USA was streamlined and terse, and High Time was a poetic monolith that should have been a breakthrough, but they were all great in their own way—evoking concepts, imagery and worlds alien to ’80s conformity. The same thing that spoke to musicians spoke to me as well, even if by that point all five members were living in relative obscurity.

Two of the MC5, Tyner and guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, died in 1991 and 1994, respectively—right on the cusp of the band going from cult underground phenomenon to elder statesman. CD reissues of all three albums proper in 1991 and 1992 hastened that higher profile, as did several albums worth of previously unreleased material that same decade, and by the 2000s survivors Kramer, Thompson and bassist Michael Davis were able to parlay that newfound (if minor) recognition into the DKT-MC5 with various side men—a project that ended with Davis’ death in 2012.

The legacy won’t end now that all five are gone. Heck, even the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame finally recognized them in its musical excellence category this year. As long as there are musicians with a rebellious streak or people who simply want to hear high-energy rock ’n’ roll, the MC5 will live on. Neither will be in short supply anytime soon—if ever.