-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Charles Bukowski 100 Years On

By Harvey Kubernik

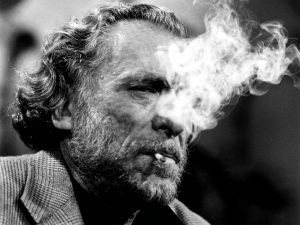

AUGUST 16, 2020 marks the 100th birthday of short story writer, columnist, poet and novelist Charles Bukowski, born Heinrich Karl Bukowski in Andernach, Germany, who relocated with his parents to Los Angeles California at age three. His literary work and lifestyle has influenced numerous writers, actors, musicians, and songwriters. Especially Tom Waits, particularly on his song “Frank’s Wild Years.” In the late sixties Tom had been a devoted Bukowski fan and devoured his weekly Notes of a Dirty Old Man column in The Los Angeles Free Press.

The Arctic Monkeys referenced Bukowski in “She Looks Like Fun” on Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino. Richard Ashcroft of the band Verve called his debut solo album Alone With Everybody after a Bukowski’s poem. Bands name-checked Bukowski in their albums over the decades: The Red Hot Chili Peppers’ “Mellowship Slinky in B Major” off their Blood Sugar Sex Magik and the Boo Radleys’ “Charles Bukowski is Dead” on Wake Up! Dave Alvin’s Museum of the Heart mentions him in “Burning in Water Drowning in Flame.” Modest Mouse and Kasabian acknowledge Bukowski in lyrics. There’s even a Florida-based group Hot Water Music that took their moniker from his collection of stories of the same title. U2 on Zooropa paid tribute to him with “Dirty Day.” During interviews, Ric Ocasek and Kurt Cobain hailed his literary efforts.

Bukowski was a classical music fan, who had little regard for rock music and basically anyone associated with it or attempting to employ his name or well-intended homage. His love for classical music is echoed by many who admire this genre, it is still cherished to this day with classical music players recreating famous sheet music (they can click here for more information) as well as mash-up different pieces to put their own spin on it. Who knows if Bukowski would like this type of classical mixing, but it certainly brings a modern-day feel to the genre.

His headstone at Green Hills Memorial Park on 27501 S Western Avenue in Rancho Palos Verdes, California reads “Don’t Try.”

On August 21, 2020 Real Gone Music a reissue record label dedicated to servicing collectors and the casual music fan celebrates Bukowski’s birthday with Charles Bukowski Reads His Poetry, a limited 100th Birthday Vomit Vinyl Edition of his 1972 release on John Fahey’s Takoma label, from September 14, 1972 at City Lights Poets Theater in San Francisco. John Van Hammersveld designed the original album cover graphics [above]. John created LP covers for the Rolling Stones, Beach Boys, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, PiL, Blondie, and the American edition of the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour.

“We rented the Williams’ Book Store in downtown San Pedro for two years,” John told me in 2020. “Had shows there and met the community. It was once Bukowski’s hang out. In 2009 it closed after 104 years,” lamented the current San Pedro resident who drew the iconic Endless Summer poster.

Van Hamersveld recently created a print honoring Bukowski. Shepard Fairey, Jeff Ho and I were interviewed for the Chris Sibley & David Tourje-directed short documentary John Van Hamersveld: Crazy World Ain’t It which had a world premiere in February 2019.

Daniel Weizmann edited the book Drinking With Bukowski Recollections Of The Poet Laureate of Skid Row published by Thunder’s Mouth Press in 2006. Front cover illustration was by R. Crumb. I was invited to contribute.

A new documentary was released on various streaming services on August 7, 2020, You Never Had It – An Evening With Charles Bukowski, directed by Matteo Borgardt.

Time to tout Bukowski’s 100th birthday with my non-edited memoir text assembled before Weizmann’s book was published.

I’M PRODUCING STEEL, MAN

By Harvey Kubernik 2016.

MEN AND WOMEN occasionally ask me about the Doors and Charles Bukowski. I was fortunate to witness them both in live performances during 1968-1980.

Passionate fans and record collectors know Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek are graduates of the UCLA Film School but pleasantly surprised finding out drummer John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger are natives of Los Angeles. However, the inquisitives are actually sometimes stunned when they discover Bukowski is a product of Los Angeles High School, the oldest public high school in the Southern California region. The same institution that gave us John Cage, Ray Bradbury, Mel Torme, Budd Schulberg, Anna May Wong, Piper Laurie, Dustin Hoffman, Marilyn McCoo, George Takei, Dick Walsh, Frederick Madison Roberts, and Leonard Slatkin.

I first read wordsmith Bukowski’s weekly newspaper Notes of a Dirty Old Man column in The Los Angeles Free Press when I was at Fairfax High School 1966-1969 and later during college at San Diego State University. Bukowski’s street life “documentation” of Hollywood and LA in Art Kunkin’s The Los Angeles Free Press and John Bryan’s Open City was raw and regional, warning me about the omnipresent perils of lust, liquid adulthood and betrayal in the neighborhood.

In Drinking With Bukowski Recollections Of The Poet Laureate of Skid Row I recommended to editor Weizmann the author of numerous biographies and cultural histories of the Beat Generation, the Beatles and sixties counterculture Barry Miles to participate in his Bukowski-centric vision.

In 1969 Miles was the label manager of the Beatles-owned Zapple Records, an Apple Records subsidiary run by Paul McCartney’s friend Barry Miles. It was a budget division intended for spoken word and avant-garde recordings. Barry recorded William Burroughs, Richard Bautigan, and Allen Ginsberg for the label. During February 1969 Miles’ Ampex 300 tape recorder and microphone captured Bukowski inside his East Hollywood apartment at 5125 De Longpre Avenue.

As it turned out, Miles had provided Bukowski a turning point in his career. “A few weeks after making the recording he gave his first poetry reading,” Miles wrote in his “Bukowski on the Mic” chapter in the compilation. “A year later on January 2, 1970, at the age of forty-nine, he finally quit his job at the post office and devoted himself full time to writing. He couldn’t get away from the post office, however; it became the subject of his first novel, called, unsurprisingly, Post Office, published by Black Sparrow in February 1971.”

Bukowski’s poems and stories were eventually republished in collected volumes by John Martin’s Black Sparrow Press (now HarperCollins/Ecco Press).

I went to one of Bukowski’s poetry readings in 1972 at the Papa Bach Bookstore in West Los Angeles. Charles was angry and combative with the audience of 60. Poet/actor Harry E Northup was there. I met the store’s owner John Harris. I would work with both of them in the future.

I was seated near Bukowski in 1975 at a Rolling Stones’ Inglewood Forum concert. He reviewed the show for Creem Magazine and I covered it for Melody Maker.

In 1976, I went over to the Free Press Hollywood Boulevard office for a party. Charles Bukowski was at this get-together. We were formally introduced. Charles suggested to a friend of mine to make a liquor store run across the street. Then Bukowski started to make a move like professional baseball player Maury Wills at Dodger Stadium stealing a base bag for the home team. I monitored Bukowski’s actions like a slow-motion re-run of the Zapruder film. Charles approached a friend’s wife who had a ring on her finger. He attempted some suggestive talk. She handled the awkward proposition, laughed, but was a bit shaken afterwards. The man and his wife, now a lawyer and author, split the scene.

I seem to remember I tapped Bukowski on the shoulder, uttering something like “Hey, man, that wasn’t very nice.”

“Shut up!” was his immediate response. Then the beer arrived.

I thought Bukowski was rude. I don’t care if years later he would call it “research.”

I have a fond memory of Bukowski’s 1976 Troubadour club appearance on Santa Monica Boulevard. Louie Lista was the bartender, Paul Body the door man got one of his Bukoswki books autographed, and the club’s manager, Robert Marchese, who previously was Richard Pryor’s record producer, oversaw the engagement. Marchese asked Bukowski if he needed anything before the gig “A six-pack of Heineken beer.” It was finished rather quickly. Bukowski met his future wife Linda Lee Beighle at this show.

Under that gruff exterior Bukowski was a person who seemed to have stage fright when describing the social, sexual, economic, cultural ambiance of Los Angeles to us.

In 2000 I talked with singer/songwriter Stan Ridgway, formerly with Wall of Voodoo who witnessed Bukowski’s Troubadour booking. Stan praised Charles’ “direct writing style, the funniest, the way of turning a very bleak situation into something that he overcame.”

Denny Bruce, the original drummer with the Mothers of Invention during their 1965 period was also in attendance. Denny is a record producer who did albums with Leo Kottke, John Fahey, John Hiatt and the Fabulous Thunderbirds. Bruce was co-owner of Takoma Records, a groundbreaking roots music independent label. Denny had met Bukowski a few times over the years, once at his apartment, and at a mid-‘70s reading in Culver City at the Robert Frost Auditorium. They had a mutual friend, performer Bob Lind of “Elusive Butterfly” fame, whose parents had flown in from Denver for the occasion, who cringed when a passionate Bukowski berated the small audience for “not being good enough to hear this man’s music.”

In 1978, or ’79, Denny’s label released Charles Bukowski Reads His Poetry a live LP culled the San Francisco performance. When that LP was first available, a small press party was held on Sunset Boulevard, down the street from the Takoma/Chrysalis office at Scandia restaurant that served tasty Swedish meatballs. At the reception Bukowski got totally drunk, freaked out some of the restaurant patrons, and was tossed out of the establishment.

Excerpts of that same San Francisco appearance were utilized in the 1973 Taylor Hackford-directed and produced Bukowski documentary that was broadcast on KCET-TV the Los Angeles market Public Broadcasting System station. During 1971-1973 Hackford helmed several films at KCET including the Cat Stevens documentary Boboquivari and a Leon Russell live in- studio session Homewood.

In 2007 I spoke with Hackford at the Mods & Rockers Film Festival event at the Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Blvd honoring the songwriting team of Mike Stoller and Jerry Leiber. Taylor mentioned that while on the plane ride to San Francisco for the Bukowski reading and taping, Bukowski asked him to select the poems to be read at the appearance. Hackford also disclosed that many years later he approached KCET about putting together a DVD of the unaired footage and previously not included performances, and learned the station had wiped the footage from their library.

In 1980 Denny Bruce arranged to produce another live Charles Bukowski taping in Redondo Beach at the Sweetwater Inn, a blues, rock and pop music venue and asked me to be involved as production coordinator. Bruce had done his homework and knew the Bukowski book catalog. He lent me some of the titles before we rolled the tape machines.

A few weeks before, Joe Wolberg at City Lights in San Francisco had mailed to Denny’s home in Bel-Air the first treatment for the proposed film of Bar Fly, that director Barbet Schroeder was putting together with James Woods and Karen Black in the lead roles. I eagerly read the pages. When the movie was cast, it starred Faye Dunaway and Mickey Rourke. Fred Roos was the producer.

We jumped on the 405 Freeway and schlepped over to The Sweetwater in Denny’s BMW. I was introduced to Barbet who was setting up a film camera to capture the proceedings. He was impressed I was aware of his 1969 directorial debut More which utilized the music of Pink Floyd. Barbet was delighted that I knew Don Hall, the music coordinator who had been a deejay years ago on local radio station KPPC-FM. Pink Floyd wrote the soundtrack for La Vallee, his 1972 movie that was issued as the LP Obscured by Clouds.

As a teenager Schroeder lived in France and studied at the Sorbonne in Paris. During dinner I told him about the Toho La Brea Theatre foreign movie art house on 857 S. La Brea Ave. in Los Angeles where his films along with other French New Wave directors like Jean-Luc Godard and Jacques Demy were screened until 1974.

Barbet howled when I gladly confessed “I wasn’t into cinema with sub-titles. And the only reason I saw The Model Shop was because Spirit did the music.”

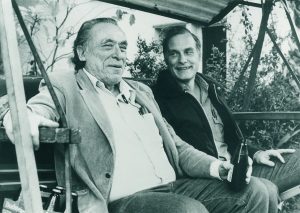

Charles Bukowski with Barbet Schroeder.

I was given a full access pass and invited to take a view into Schroeder’s camera lens as he blocked shots while I assisted Denny Bruce at the soundboard.

In 1985 Barbet produced a documentary The Bukowski Tapes. Four hours and fifty-two clips of Bukowski ranting and ruminating.

The anticipation of this particular Charles Bukowski poetry reading reminded me of The Last Waltz, a sonic and filmic event I reviewed for Melody Maker in November 1976. And, like Bob Dylan, circa 1966-73, Bukowski wasn’t performing often around his hometown.

Ninety per cent of the crowd seemed to be students from Cal State University Long Beach. Eddie Call, then in the Marina Swingers band, was the bartender. Call and staff were instructed to serve Bukowski. Eddie later informed me there was no tip at the end of the night.

Writer Kirk Silsbee and his girlfriend, Cathie Gentile, attended. Now married, they had seen Bukowski read in ’76 at Sweetwater, as did Michael Gira, Kirk’s boon coon from the El Camino College Art Department. Gira was years away from forming his band Swans but he was seriously writing poetry while living in a Hermosa Beach garage and scamming art money grants.

“At the Sweetwater there was a young guy,” Silsbee recalled, “opening for Bukowski. He looked like Jackson Browne, played the piano and sang those ‘sensitive guy’ songs that you used to hear in the ‘70s. At one point he asked for a white wine. Later, as Bukowski chugging his way through six-packs between poems and insults, he affected this sissified voice and said, ‘Could I have a white wine please?’ The place roared but the poor bastard asked for it.”

I handled the Ampex 456 tape boxes, sorted out reels and tested microphones locations. Denny Bruce oversaw the recording operation like General George Patton and navigated the playing field like Hall of Fame footballer Jim Brown. It was apparent, that over the years, Bruce really wanted to do a proper recording with Bukowski. He’d been in discussion with Charles for a decade. At the Sweetwater club, Bukowski drank four bottles of wine out of a water tumbler.

There were a lot of geeks in the house. Guys with first edition books begging for autographs, frat rats shoving their own writings at Bukowski, “Check out my stuff on computer!” and a whole bunch of fan boys with ancient columns, now yellow with age, wanting Bukowski to personalize the newsprint with an autograph.

A bouncer at the Sweetwater entrance looked at me and confided, “Hey…I’m used to ‘Blues queers’ crowding the dressing room.”

There were some very attractive women in the house, hugging, kissing, congratulating and fawning all over him.

One memorable moment occurred, as on cue from his own self-penned B-movie biopic, a drunken Bukowski turned to Denny and myself, pondering, “Why does all the cunt show up at age 54?”

Did we not admire his honesty, humor, observations and erotic reflections on the page and public stage?

Afterwards, Denny asked me to guard his master tapes and equipment as he and Bukowski went to another room with Richard the club’s co-owner. I heard noises and a hassle occurred. We knew the payment fee was taken care of well before the booking. In fact, the wad bulged out of Bukowski’s front pocket. Bukowski then pulled a penknife out and jabbed it right into the desk of the owner asking for his money, forgetting he’d already been paid. Everyone tried to calm him down and then Charles reached for a smaller knife and proclaimed, “I’m producing steel, man.”

Bukowski’s friend, Joe Wolberg managed to put him into a headlock and then took him away. There was a lot of static in the room and Bukowski’s final words of the night were “the only reason you booked me into this clip joint was that you could hit on [his wife] Linda.” He obviously loved her.

Before the first retail configuration of Hostage came out, Denny and I thought it would be a good idea for German film director, Wim Wenders, to write the liner notes for a projected German territory distribution. Wim was very receptive, invited me to the set of Hammett in 1981 that he was doing for Zoetrope Studios at 1040 N Las Palmas Avenue.

Wenders had been a music journalist and critic, liked the Germany-born Bukowski, and we both understood the market for a German audience that existed for his catalog. The liners didn’t materialize, but in 1999 I bumped into Wenders backstage at a Tom Waits concert in Los Angeles at the Wiltern Theater. We were reintroduced and he mentioned he still had the original disc I sent him.

I remember when the first pressing was pressed, a vinyl-only Hostage issued in the mid-’80s produced by Denny Bruce. Poet/writer Kenneth Funsten did the liner notes for the album.

I mailed a copy to teen scribe Shredder aka Danny Weizmann, then a student at UC Santa Cruz, and living in a college dormitory. He played the Hostage LP at full blast one night with some friends, and was asked to leave the dorm the following morning.

Well, I always knew Hostage was a rock ‘n’ roll record.

I even had to talk to his mother over the telephone about the incident but also guaranteed her son would be a great writer. I suggested for him to transfer to UCLA for their Creative Writing program. He graduated with a BA in English Literature. He later wrote Hardcore California: A History of Punk and New Wave and is a voice in every one of my books since 2002.

“There were other great LA writers before Bukowski but he might be the first really great LA native,” volunteered Weizmann. “For those of us who are from here, one of the pleasures of reading him is the way he represents local dimensions-it comes up in curious ways. For instance, a writer from the east might never mention the bowling alley off Hollywood Boulevard or a Safeway Supermarket, because they’re too citizen-level, they don’t evoke all the old cliché literary visions of Tinsel Town. But in one of his early columns, Bukowski writes about staggering by that bowling alley, hungover at dawn.

“First time I read it, I got goosebumps, because my late aunt Ethel used to take me to that empty low lit place where the diehards practiced alone, the old men lined up the bar, and the vending machines sold non-slip grip cream and mini sewing kits in little plastic eggs for a quarter. By making poetry and spirit out of the day-to-day world we lived in, Bukowski showed that everything could be dramatic, everything could have a spiritual resonance, and it follows that every soul in that world counts. In that way he’s like Walt Whitman or Lou Reed, giving voice to the hidden and the ignored.”

In a twenty-five-year period before Bukowski’s death, I bumped into Bukowski a few times in the Southland.

In 1983 Bukowski and I chatted at the opening of director Ron Mann’s Poetry In Motion documentary on Wilshire Blvd at The Four Star Theater in Los Angeles. Ed Sanders, Amiri Baraka, Allen Ginsberg, Diane Di Prima, Michael McClure and Tom Waits on the big screen. The same room I first saw A Hard Day’s Night, The Graduate and where director John Cassavetes filmed portions of his Opening Night film. We reminisced about the downtown Central Los Angeles Public Library where he first discovered John Fante, and Los Angeles City College. Bukowski took a creative writing class many years before I received a few credits in their literature department.

Charles was caught off guard when I brought up Los Angeles High School. “I’m from Fairfax High School.” “Kid, that’s in West Hollywood… I lived in East Hollywood.”

We definitely worked different sides of Western Avenue. I never drank and ate at El Cholo and Ole Sole Mio Pizza parlor. Bukowski cruised Stan’s Books, and frequented local bars.

Once in late December 1985 after visiting the minutemen’s D. Boon I encountered “Hank.” Boon lived in the Point Fermin area, and the weekend just before he died in a car accident we did a show at the Lhasa Club in Hollywood. Boon and his band member Mike Watt directed me to a restaurant Seven Seas for a meal. The place was closed, so I schlepped over to Ports-of Call in San Pedro to eat some cioppino. I entered the vast parking lot, found a spot, and next to me was a black BMW and out popped Charles Bukowski. He had the Racing Form tip sheet in his hand and obviously on the way to the Hollywood Park Racetrack in Inglewood. It was daytime. Charles nodded, smiled, and said hello. Bukowski had sparkling blue eyes like Eva Marie Saint and Bob Dylan.

Charles then drove off to Hollywood Park. My friend, singer/songwriter Tom Johnson caught him at a betting window and called me that evening. In the seventies Tommy lived down the street from Bukowski on De Longpre Ave.

Only a couple of days before I was in the recording studio with poet John Thomas who told me a hilarious story about the time he and Bukowski got kicked off the airwaves for their “use of language” one night at radio station KPFK-FM in North Hollywood. Poet and broadcaster Paul Vangelisti worked at KPFK-FM as Cultural Affairs Director between 1974-1982 who published Anthology of LA Poets, co-edited with Bukowski and Neeli Cherkovski.

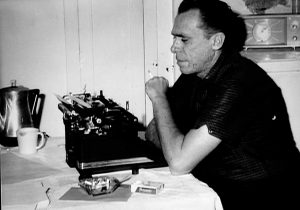

Charles Bukowski toiled on his Lazarus typewriter with a portable radio always tuned to KUSC-FM, the Los Angeles classical radio station.

I went to the October 30, 1993 U2 concert at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. Drummer Larry Mullen of the band did a stage dedication of “Dirty Old Town” to Bukowski. Bono had sent a car for Charles and his wife Linda to come to the show. Sean Penn, an acquaintance of Bukowski had made the arrangements by phone in Ireland.

Charles Bukowski died on March 9, 1994 in San Pedro, California at age 73 of Leukemia.

In late 1994 I produced a poetry reading in San Pedro at Vinegar Hill Books featuring Harry E. Northup and Holly Prado. Linda Lee Bukowski, his widow, came to our event. She smiled when I said I was keeping tabs on her and heard that Dave Alvin of the Blasters the day before had visited their San Pedro home.

During July 1995 Linda attended The MET Theater Rock ‘n’ Roll Literature Series I curated and helped produce in East Hollywood. A few blocks from 5125 De Longpre Ave. Dave Alvin, Kirk Silsbee, Paul Body, Daniel Weizmann, David Ritz, Lewis MacAdams and I read one evening. The three remaining members of the Doors reunited and performed “Peace Frog,” “Love Me Two Times” and “Little Red Rooster.”

I never realized how popular Charles Bukowski was in Europe and the UK. Paul Body told me in the last half of the eighties a television station in Paris signed off every night with Bukowski reading one of his poems on screen!

In 2006 the Huntington Library, Art Museum in San Marino California began acquiring Charles Bukowski’s papers as a generous gift from his wife Linda. The library is very near the Santa Anita Race Track one of Bukowski’s haunts.

During August 1985 I received a telephone call from record producer, musician, and songwriter, Andy Paley. I was on a Paley Brothers recording session at Gold Star in 1978 that Phil Spector produced, “Baby, Let’s Stick Together.” Phil Seymour, Rodney Bingenheimer and I provided handclaps on the studio date with members of the Wrecking Crew. It’s out on The Paley Brothers: The Complete Recordings via Real Gone Music. Andy, his brother Jonathan, Rodney and I added some percussion and handclaps on the Spector-produced Ramones’ End of the Century album. In 2002, it was reissued on CD and I penned the liner notes for the package.

Andy Paley produced the Dick Tracy soundtrack and had songs on Madonna’s album I’m Breathless. In conversations with Madonna, she revealed to Andy that she was a huge fan of Charles Bukowski. Andy subsequently called me about getting a signed Charles Bukowski book for a wedding gift for her and soon-to-be husband Sean Penn. On my message machine, he said he’d later explain the request to me. So I called back, left a voice mail and told him to go over to the Baroque Book Store on Las Palmas Ave. in Hollywood owned by Red Stodolsky, a good friend of Bukowski, who carried rare autographed Bukowski books.

Andy left a very pleasant thank you on my machine after he had gone to the bookstore and bought an autographed copy of Ham on Rye. I thought “What a cool wedding present.”

I didn’t see or talk to Andy for nearly 20 years, but in 2003 I saw him at a birthday party for Rodney Bingenheimer.

“By the way…How did that Bukowski book wedding present ever work out?” I asked. “Well…let me tell you,” Andy replied and sighed. “It was a wedding gift for Madonna and Sean Penn. And, months after the wedding I ran into Madonna in LA. ‘Thanks for that Bukowski book. You know you created a monster. Sean is obsessed with Bukowski now and they’re inseparable!’

“She was half-kidding but I know there was something there.”

Harvey Kubernik

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For 2021 they are writing and assembling a book on Jimi Hendrix for the same publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in July published Kubernik’s 520-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Kubernik interviews with DA Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, John Ridley, Curtis Hanson, Dick Clark, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. He was the project coordinator of the recording set The Jack Kerouac Collection.

During 2006 Harvey Kubernik spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress that were held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted on May 2020 on the EPIX/MGM television channel.

Kubernik has just penned a back cover book jacket endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada, will be publishing this fall 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years).

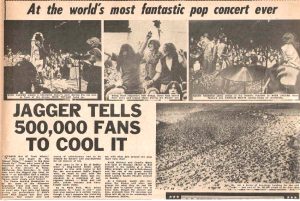

Speedway to Hell: More Twisted Tales from Altamont

By Doug Sheppard

FIVE MONTHS BEFORE there were four dead in O-Hi-O, four were dead at a forlorn, neglected racetrack roughly 50 miles east of Oakland, California: one drowned, one stabbed and two mowed over in a hit-and-run. What had aspired to be an East Coast Woodstock turned into a real-life bad trip for 300,000 on December 6, 1969 — underscored by a strain of bad acid being passed around and Hells Angels taking their (inexplicable) security duties way too far. Parking was inadequate, health services nearly nonexistent, food and water scarce — and the grass was brown, not green.

Because of the murder of Meredith Hunter as the headlining Rolling Stones played “Under My Thumb,” the Altamont Speedway Free Festival has been immortalized for all the wrong reasons. It’s been the subject of film (Gimme Shelter) and various tomes — perhaps most noteworthily Joel Selvin’s exhaustively researched 2016 book Altamont.

As Selvin put it, everyone who attended Altamont had a story. Here are three more, from the vantage point of the front of the crowd, near the front and toward the back.

THE INTERVIEWEES

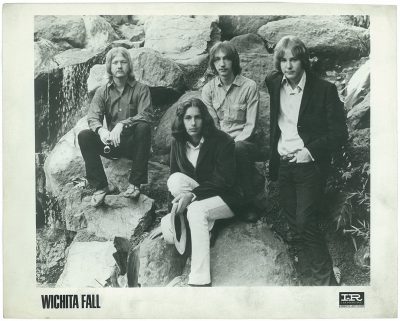

Len Fagan: drummer/raconteur/promoter/writer. Among many other ventures, released albums on major labels with Wichita Fall and Stepson, toured with his close friend Arthur Lee, and booked the Coconut Teaszer club in Los Angeles from 1987 to 2000.

Buzz Clic: guitarist for the Rubber City Rebels and the Buzz Clic Adventure.

Danny Benair: drummer for the Quick, the Weirdos and the Three O’Clock, among other noteworthy combos.

ANTICIPATION

The Rolling Stones’ 1969 tour, their first of America in three years, was met by sellout crowds bustling with enthusiasm that cemented their reputation as rock ’n’ roll gods. Viewing the footage fifty years later, one can still feel the palpable connection between artist and audience feeding into each other. So when the Stones announced that a free concert was planned for December 6 in the Bay Area, the excitement went into overdrive.

Fagan: “As soon as I heard about it, I decided I had to be there, because I had seen several of the Stones’ concerts since 1964. I was at the first concert that they ever gave in America, which was here in LA.”

The first US Stones show happened at the Swing Auditorium (a venue Fagan would later play with Stepson) in San Bernardino on June 5, 1964. Though only in his early teens, fellow Southern California resident Benair too had seen them at the Forum in Inglewood just weeks earlier — on November 8, 1969 (even shooting some Super 8 footage). When he and his 19-year-old brother Jonathan heard about the free show on the radio the night before, they — like Fagan — knew they had to be there.

The 22-year-old Fagan would travel in style, zooming up behind the wheel of his recently deceased father’s gold 1969 Cadillac Coupe Deville convertible.

Fagan: “Since I had to go over to where the car was and start it up and drive it a little every week, which I did, I decided this would be a good run for the car: LA to Frisco. Now I had room to take a few friends with me, and I invited my best friends; two decided to come along. One was a very close friend of mine named Frank ‘Chappy’ Chapman. The other was at the time my very best friend, Darryl DeLoach, former lead singer of Iron Butterfly. The ride up there was nothing but fun.”

The Benair brothers — along with a friend named David and Jonathan’s girlfriend Bonita — were considerably less fortunate on their trip up from their Panorama City base in Jonathan’s Ford Galaxy.

Benair: “As we were driving up the night before, a rock hit my brother’s gas line, and we had to stop in Tulare at about 5:30-6 in the morning and wait until 8 for a gas station to open that could repair the gas line on my brother’s car.”

Clic, who was 20 and living in San Jose, had a considerably shorter journey. Like his housemates — including his brother Carl and brothers Bill and Mike Davis (also all in their early 20s) — he’d moved to the West Coast from his native Hudson, Ohio, a then-small town roughly halfway between Cleveland and Akron. The concert fit the type of activity the four sought when they relocated.

ARRIVAL: THE UNEASINESS BEGINS

Owing to proximity, the four ex-Ohioans arrived early the morning of the show.

Clic: “We drove up there the day of, real early in the morning. And when we got there, there was like 10 billion cars, so we had to park miles away, because there was no real actual parking lot. There was just people parked on the side of the road, and you walked. We had to walk like a mile.”

Clic was already aggravated — “It was a long time, it was hot, and I was not happy that I had to walk that far” — and seeing the venue didn’t help matters. As opposed to the picturesque trees and grassy fields that reflected the bucolic splendor of Woodstock, Altamont was brown hillsides dotted with twisted metal, broken fences and the rusting remains of demolition derby cars.

Clic: “It was burned-out California desert, and it was all rundown. There was a lot of rickety old chain-link fence, and it was just a big fuckin’ dump.”

High on pot and LSD, the four settled down onto a blanket roughly 100 yards from the stage — occasionally swigging the water they brought along.

The Fagan party also had a good stash.

Fagan: “A couple of the other friends who I invited asked me: ‘Do you need any drugs for the trip?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’d sure like some mescaline or acid.’ These guys were dealers, and so they said, ‘Well, stop by the house here in Topanga and we’ll give you whatever you need for free.’”

Before Fagan could start getting high, he’d need to find a parking spot, which — thanks to arriving just before the show — proved quite difficult.

Fagan: “So we’re driving up the highway, and we see some people walking on the grass adjacent to the highway, and then as I continued driving, I saw more and more cars parked, and more and more hippies walking. Finally, it got to the point where there was only a rare parking space available — and these were all makeshift parking spaces. You know, there were no white lines painted, so I figured, ‘Well, I better take this one, because I don’t know if there’ll be another up ahead.’ Because the crowd that was walking got thicker and thicker. We figured the site of the concert must be just up ahead, so I parked and we started walking.”

Len Fagan (second from left) in Wichita Fall, 1968.

With Fagan’s unleashed German Shepherd Joe strutting beside them, Fagan, DeLoach and Chapman set off on the long walk to the venue. In an eerie foreshadowing of what would ultimately unfold, Joe repeatedly mixed it up with a Weimaraner as they walked to the festival. “He and Joe kept getting into it; every quarter- or half-mile, they’d get into a little altercation and I’d have to separate them,” Fagan recalled.

Following a lengthy jaunt that blistered Fagan’s feet, the three entered from behind the stage — only to discover that parking far away wasn’t their only concern.

Fagan: “We start walking out toward the audience, looking for a place for my two friends and my German shepherd and myself to sit crosslegged in the grass. Finally, I realize there is no more room here for us to sit. And I looked ahead of me, and I see there’s no room 100 yards back, either. [laughs]

“So I just said, ‘Fuck this,’ squeezed in-between two people with my dog, and then my friends are just a few yards behind me — and they take the opportunity to squeeze in there. The people immediately around us had to move inch by inch to their right or left so we’d have room, because I wasn’t going to settle for standing. And even if I stood, I’d be in people’s way. So we lucked out.”

They weren’t as lucky as the Benair party, who also entered from the back of the stage late thanks to their now-repaired Ford’s breakdown — settling up front, stage right.

THE CONCERT BEGINS

Chaos begat more chaos at Altamont: The stage, light towers and electrical wiring were hastily thrown together just hours before the festival started thanks to a change of venue from Sears Point Raceway to Altamont (and, before that, a failed attempt at getting permits for Golden Gate Park in San Francisco). As others have pointed out, it’s a miracle that nothing went wrong with any of the equipment. But that’s where the good fortune ended. Right after the first band, Santana, went on, the trouble started— and it would only get worse.

Fagan: “A big, huge, fat Mexican fellow took off all his clothes — and he was just a few yards to my left. And he started walking over people. Like I said, there was no room to walk in-between people; we were all so inched together so tightly. This guy takes off all his clothes, which was not a pleasant sight, and starts walking over people. And if I recall, you can see that happening in Gimme Shelter.

“It was pretty disgusting to have this guy naked walking all over you in your face. Even the Angels, no matter how rowdy and crazy they get, would never take their fuckin’ clothes off and walk over people. So that was beyond their permissiveness, I suppose. And when this Hispanic male first took off his clothes and started walking, I said to myself, loudly: ‘Oh, so this is the kind of day it’s going to be.’ And for the rest of the day, I did not forget that. I figured anything could happen here today; it’s every man for himself.”

Benair: “Very early on, there’s a very heavy, overweight guy who’s naked, and he starts screaming that he wants to play drums with Santana. I don’t know if it’s because he said that, because of his nudity, or a combination of whatever — the Hells Angels start beating him with pool cues. This is just frightening. So very early, there’s a lot of negative energy, and it’s very sporadic, but it’s very ugly.”

The fat man (who’s never been identified) was bloodied, and fighting continued during the next set by Jefferson Airplane, whose lead singer Marty Balin got pummeled in a failed attempt to stop the Angels from wailing on a concertgoer. Mick Jagger was also decked when he arrived after the Flying Burrito Brothers’ set — a scene that, according to Fagan, produced a loud, audible commotion from backstage.

“Huh,” Fagan said to himself, “this isn’t going to be Woodstock.”

Nonetheless, Fagan was duly impressed by the Burritos’ set.

Fagan: “I got very excited; I didn’t know they were playing that day, and they were one of my very favorites. So they come up onstage and they’re doing all this shit-kicker music, and boy was it great. To my taste, there isn’t enough of the Burrito Brothers’ performance on film in Gimme Shelter.”

Still, there’s more footage of the Burritos than of the next band, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — who don’t appear in the movie at all. If Fagan’s memory is correct, there may be a reason for that.

Fagan: “They made me sick. I never liked them. Believe me, their harmonies were an atrocity. They had these difficult three- and four-part harmonies, but they couldn’t deliver ’em in person, because on record, their voices were stacked, and it made them sound all sweet and full. Live, they were weak. So I had to sit through that.”

He also had to sit through a show that was rapidly spinning out of control. The beatings continued, drug casualties overwhelmed what little medical services were present, and crowd unrest grew. Under the influence of two tabs of mescaline, Fagan literally got a firsthand glimpse when — either during or shortly after the Flying Burrito Brothers’ set — he climbed one of the hastily assembled light towers.

Fagan: “I decided to climb up one and get a better view. So I get about maybe a third of the way up, maybe a little more like 40 percent up, and I’m saying, ‘Wow, this is great — what a view I’ve got! Why doesn’t everybody else climb up on these things?’”

No sooner did that thought cross Fagan’s mind then he heard shouting from the bottom of the light tower: “Hey you! You!”

“What is this? Who are they yelling at?” Fagan thought to himself after cursorily scanning the surrounding area.

Fagan picks up the story: “And then I take another look, and right at the bottom of the trust was a guy — remember, I’m on a lot of mescaline that day — that in my mind looked like a dangerous pirate. I don’t know if he had an eyepatch and teeth missing and a bandana around his head, but that’s what I saw and felt. I could have been hallucinating — who knows?”

The shouting persisted: “Hey you!” This time, Fagan looked straight down and met eyes with the shouter. “Yeah you! Get down off of there.” But a confused Fagan didn’t move.

“Hey you! Yeah, you! Somebody back there wants you down,” the shouter said, pointing to a bus roughly 45 degrees to Fagan’s right.

Fagan: “There is this big yellow school bus there with lots of Hells Angels sitting on the top, misbehaving, giving out very bad vibes. He says, ‘No, those people want you down.’ Then I said, ‘Oh … OK.’ I slowly climbed down the trust, and my faithful dog Joe is right at the bottom, waiting for me.”

The canine wasn’t the only sight to greet Fagan, who now stood under the blank, menacing glare of the Hells Angel who’d ordered him to come down.

Showing little emotion, the biker’s eyes quickly darted to Joe before refocusing on his owner. “Mean, huh?” the Angel queried.

Fagan: “Joe was far from mean, but I shook my head and said, ‘Oh yeah.’ [laughs]”

Further back in the crowd, at least several concertgoers were also growing weary of tower climbers like Fagan.

Clic: “People were doing crazy shit all day. They were climbing up on the stanchions, and so they’d be announcing from the stage: ‘We’re not going to play, no more bands are going to play until you get down off of those things. We don’t have insurance.’ The whole day was like that.

“It just seemed like there was some sort of tension going on throughout the crowd. You could feel that even from as far back as we were.”

Reasons for the tension, however, were unclear to those in the back. Other than learning about Balin’s mishap thanks to Paul Kantner confronting the Hells Angels onstage (a scene captured in Gimme Shelter), Clic said his group had no inkling of what was really going on: “Because we were so far back, the only trouble that we had noticed was when the Jefferson Airplane were playing during the day.”

WELL, YOU HEARD ABOUT THE …

Having learned of all the day’s drama and violence upon their arrival by helicopter, the Grateful Dead — who’d been pivotal in setting the show up — elected not to play. In place of the Dead’s long set came a 75-minute wait that only made things worse.

Fagan: “I can’t speak for 300,000 other people, but I know I felt very uncomfortable during the long wait for the Stones, because I knew that anything could still happen here.

“In-between bands, there was a very uneasy feeling that day. I recall saying to myself, ‘This is the most ominous day I’ve ever experienced.’ The vibes were just not good vibes, and I believe they were all stemming from the Hells Angels. And sometime during the day, we found out that there was no real security there. I figured guys from the FBI or something would be there to keep things OK, but to my knowledge there were no real authorized police there that day. So the Hells Angels could get away with anything they wanted to, and we knew it. I thought it was very sad that there were 300,000 of us and maybe 50 of them, and we couldn’t handle ourselves.”

Clic: “It wasn’t run very well. It was just this slapped up thing and the bands were kind of willy-nilly. By the time the Stones got on, it was really late at night.”

Finally, as night fell on Northern California, the Rolling Stones took the makeshift stage. Darkness descended on more than just the sky, as the already volatile situation throttled uncontrollably to its sick apex of further beatings, trampling and, ultimately, a murder. Benair, right in the thick of it, cited a Hells Angel’s bike getting knocked over as a flashpoint.

Benair: “I fell down and people started trampling me — and my brother pulled me up. So obviously, we moved at that point. About halfway through the set, we go back to the side, and because I’m so young, I jump on the back of the stage and I stand on Keith’s or Mick Taylor’s amp line. I’m back there and nobody bothers me because I’m young. My brother gets up there and a Hells Angel tells him to get off the stage, so he set up on the side. So I watched the last quarter of the set from the stage. Absolutely no one even gave me a dirty look, because I’m just too little. Even the Hells Angels weren’t going to bother with a little kid.”

Fagan: “They waited till it got pitch black, then they turned the lights on onstage, and then soon after they took the stage and started playing. But I thought that was very foolish of them and selfish to make a crowd like that wait for so long to go on.”

Nonetheless, Fagan enjoyed the set: “Boy, were they in form that day. They were playing everything on the back of the beat, if you know what I mean; none of their songs were runaway rollercoasters like some of them were on their early records. They played so nasty; the feel they had that day was so nasty, then they start ‘Midnight Rambler’ and Mick Jagger is playing with the audience.”

“Things really, really reached their peak with the Stones, because they were playing with us. They were instigating and playing with the audience, trying to get any kind of reaction they could out of us. And they did a great job of it.”

From further back, however, there was only the music to go on — making the interruptions to the Stones’ set all the more exasperating.

Clic: “The Stones had to stop in the middle of songs, and bands never do that. Whatever ruckus was going on up front was evidently playing out right in front of them, and we were so far back and it was nighttime that we were going: ‘C’mon, just fucking play. Sit down up there.’ We were just annoyed at the crowd.”

CONFUSION AND DISORIENTATION

And then, the Stones finished — albeit not quite as triumphantly as they intended, leaving the speedway in an overcrowded helicopter as 300,000 mostly stoned and drunk concertgoers attempted to find their way out in near-total darkness. Before departing, however, Benair — still standing on the stage — sensed an opportunity.

Benair: “When the show’s coming to an end, I look over at Charlie Watts — and at that point, I had just gotten a drum set. And Charlie had a crushed velvet jacket next to his floor tom, and I went over and tapped him and said, ‘Charlie, can I have your drum sticks?’ And he said, ‘yeah,’ and he gave them to me. It was something brazen I did at the moment, and I still have them.”

Other attendees’ exits were decidedly less interesting. Between the delays, false starts, disorganization, and not eating all day (Altamont offered no concessions), the four Ohioans — now coming down from drug highs — had had enough. Actually, it now just three: Bill Davis had disappeared into the crowd. His friends would have to find him later.

Clic: “We were like: ‘Let’s get the hell out of here and get to McDonald’s or something.’ And Altamont Speedway’s out in the middle of nowhere.”

Fortunately, and perhaps owing to its colorful psychedelic paint job, the three were able to find the 1965 Plymouth Valiant that got them there.

Clic: “Between all of us, we remembered where it was, but it didn’t matter, because you couldn’t move. Everybody got into their cars at about the same time, and started and tried to go, and you just have to leave single file. It took forever, and we were not in any good mood.”

But that was nothing compared to what Fagan, DeLoach and Chapman faced: They were still high, and had no idea where the Caddy was.

Fagan: “We didn’t know which way to go. And even if we knew which way to go, we didn’t know how far to go. So a god shot happened, and I run into a friend of mine named Dale, who was a friend from high school. And I asked him, ‘Could you please give us a ride back to our car?’ He said ‘sure.’

“Without that, man, I don’t know what would have happened to us. We start driving back along the highway where thousands and thousands and thousands of cars were parked. In fact, about a half-mile or so before the site of the concert, cars are not only parking on the side of highway, but they’re parking in the right lane of the highway — right on the highway. It’s like they just abandoned their cars and walked to the show, which I found fascinating. I would never do something like that, man. That’s dangerous.

“I don’t know if this is accurate or not, but I seem to remember finding the car in the early daylight. We’re driving down the highway that we walked up to the show on, and there’s the Cadillac sitting there, all by itself — like we were the last ones to get back.”

A glance at his friend’s odometer gave Fagan an even bigger shock: They’d parked 14 miles from the site.

Fagan: “After the show, we were certainly in no condition to walk 14 miles. So that’s why I call that a god shot.”

Compared with Fagan and Clic, Benair — tagging along with three elders — got off easier: “Because we parked behind the stage, we got to our car much quicker than most people. Getting out took a long time for everybody.”

Though Fagan had heard rumors of the Hunter murder at the end of the show, Benair and Clic (like most attendees) didn’t find out until the next day — adding to the drama of an already unsettling experience.

Benair: “Having been in bands, having seen 2 trillion concerts, I can say I’ve never been to anything even remotely close to that in terms of just the negative energy that you could have cut with a knife. It was just alarming. You know, I’ve been to shows where there’s definitely some bad vibes coming from the room, but nothing even close to that. It was one of those things where being so up close and personal made it even weirder because if I’d been far away, I would have just experienced this little dot of music — and I may not have even felt the energy was negative, other than the Stones saying stuff.”

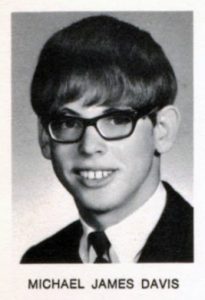

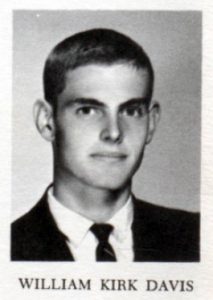

Jonathan Benair (center in glasses) at Altamont.

Clic: “We were reasonably satisfied that we saw those bands for free, but at the same time, it was a long day and it wasn’t a groovy trip. The whole day was just a bummer.”

In the aftermath, Jonathan Benair would appear prominently in a photo of Rolling Stone’s coverage of the event. Sadly, he passed away in 1998.

BACK TO ALTAMONT

Buzz, Carl and Mike Davis (who died sometime in the ’80s) were finally back in San Jose by the wee hours of December 7, but their business was not finished: They had to find Bill. And the only place to start the search was back where they last saw him: the now controversial Altamont Speedway.

Clic: “One by one, everyone went looking for Bill. And what ended up happening is Bill had stayed at Altamont and had started cleaning up — just being part of the cleanup crew. And so we ended up going back there and found him, and we were about out of options anyway at the place — because we didn’t have enough money to pay for the next month’s rent. So we ended up staying at Altamont, and we’d go out everyday under the guise of cleaning up.

“People had just left everything; it was just blankets and bottles and junk everywhere. But there was an unlimited amount of free drugs; there were probably about 20 people there, and we were staying above the stands in a press box. We were sleeping on the floor in there, and going out in the daytime and picking up crap. And then we’d come back and everybody would kind of throw whatever drugs they’d found on the table, divvy it up between us, and get high.”

Soon, the four met Altamont owner Dick Carter (who has a cameo in Gimme Shelter) — finding further employment at his San Leandro body shop once the racetrack was cleaned up.

Clic: “We spent about two weeks, maybe longer, cleaning up the place. By that time, we met Dick Carter, and we knew a lot about cars and hot rods, so we talked to him. He picked up that we knew stuff about cars and that he could use us. So that’s how we ended up going to his hot rod shop, then we just moved on from there.

“We ended up moving into the back of his body shop. He had race cars back there — Mustang GT 350s and everything. So we were sleeping on the floor back there, but we’d work for him. He had a pool in his backyard that was all trashed out, and we cleaned it all up. And he had a couple of friends along the same road that his hot rod shop was on; there were used car lots all over the place. So when we weren’t working for him, we could walk down to the car lot guys — and there’d be twenty or thirty cars there in the used car lots, and we’d wash cars.”

It was enough to keep them busy, but it wasn’t quite the idyllic California life Clic had envisioned. Tired of the hippie lifestyle, he cut his hair, moved back to Hudson and got a real job that allowed him to purchase his first guitar in early 1970. So at least in one case, Altamont had a positive effect.

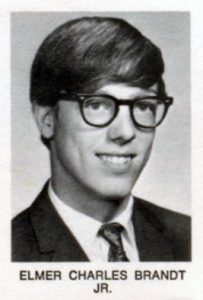

The photos of Carl Brandt and Bill Davis are from the 1965 Hudson High School yearbook, while the photos of Mike Davis and Elmer Charles Brandt Jr (aka, Buzz Clic) are from the 1967 yearbook.

Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and The Big Bopper Remembered 60 Years On

By Harvey Kubernik

February 3, 2019 is the 60th anniversary of tragic airplane crash that subsequently became known as “The Day the Music Died,” sadly referenced in Don McLean’s song, “American Pie.” Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. Richardson a.k.a. The Big Bopper died along with pilot Roger Peterson. After a February 2, 1959 “Winter Dance Party” show in Clear Lake, Iowa, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. Richardson took off from the Mason City airport, in a three-passenger airplane that Holly chartered piloted by Roger Peterson during inclement weather. It crashed into a cornfield in nearby Macon City, Iowa, just minutes after takeoff.

I will always remember the February 3, 1959 front page headline in The Los Angeles Evening Mirror-News, a daily newspaper who reported this accident.

Ritchie Valens’ death was a very big regional loss. He was from Pacoima, a suburb in Southern California. Ritchie’s records were very popular in Los Angeles and the surrounding communities. It was KFWB-AM deejay Gene Weed who first spun his music and the radio station held what seemed like an all-day shiva celebrating the life of Valens, whose record label, Del-Fi, was based in Hollywood.

I knew Buddy Holly from his appearances on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and from 1957 when he was on The Ed Sullivan Show. Holly’s records were also spun on KFWB. “Chantilly Lace” by the Big Bopper was a national hit.