-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

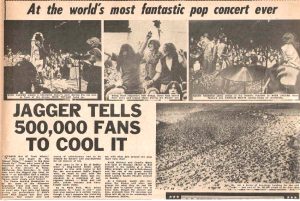

Speedway to Hell: More Twisted Tales from Altamont

By Doug Sheppard

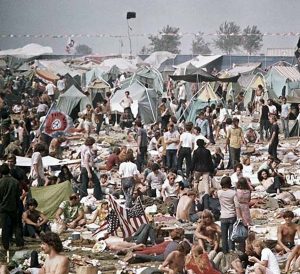

FIVE MONTHS BEFORE there were four dead in O-Hi-O, four were dead at a forlorn, neglected racetrack roughly 50 miles east of Oakland, California: one drowned, one stabbed and two mowed over in a hit-and-run. What had aspired to be an East Coast Woodstock turned into a real-life bad trip for 300,000 on December 6, 1969 — underscored by a strain of bad acid being passed around and Hells Angels taking their (inexplicable) security duties way too far. Parking was inadequate, health services nearly nonexistent, food and water scarce — and the grass was brown, not green.

Because of the murder of Meredith Hunter as the headlining Rolling Stones played “Under My Thumb,” the Altamont Speedway Free Festival has been immortalized for all the wrong reasons. It’s been the subject of film (Gimme Shelter) and various tomes — perhaps most noteworthily Joel Selvin’s exhaustively researched 2016 book Altamont.

As Selvin put it, everyone who attended Altamont had a story. Here are three more, from the vantage point of the front of the crowd, near the front and toward the back.

THE INTERVIEWEES

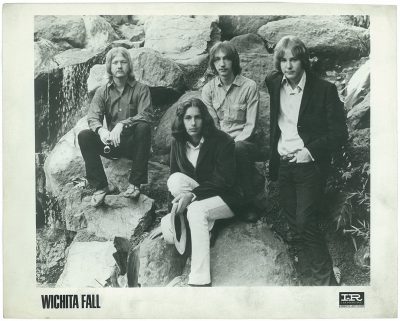

Len Fagan: drummer/raconteur/promoter/writer. Among many other ventures, released albums on major labels with Wichita Fall and Stepson, toured with his close friend Arthur Lee, and booked the Coconut Teaszer club in Los Angeles from 1987 to 2000.

Buzz Clic: guitarist for the Rubber City Rebels and the Buzz Clic Adventure.

Danny Benair: drummer for the Quick, the Weirdos and the Three O’Clock, among other noteworthy combos.

ANTICIPATION

The Rolling Stones’ 1969 tour, their first of America in three years, was met by sellout crowds bustling with enthusiasm that cemented their reputation as rock ’n’ roll gods. Viewing the footage fifty years later, one can still feel the palpable connection between artist and audience feeding into each other. So when the Stones announced that a free concert was planned for December 6 in the Bay Area, the excitement went into overdrive.

Fagan: “As soon as I heard about it, I decided I had to be there, because I had seen several of the Stones’ concerts since 1964. I was at the first concert that they ever gave in America, which was here in LA.”

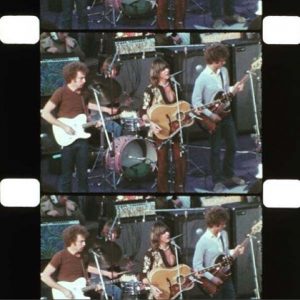

The first US Stones show happened at the Swing Auditorium (a venue Fagan would later play with Stepson) in San Bernardino on June 5, 1964. Though only in his early teens, fellow Southern California resident Benair too had seen them at the Forum in Inglewood just weeks earlier — on November 8, 1969 (even shooting some Super 8 footage). When he and his 19-year-old brother Jonathan heard about the free show on the radio the night before, they — like Fagan — knew they had to be there.

The 22-year-old Fagan would travel in style, zooming up behind the wheel of his recently deceased father’s gold 1969 Cadillac Coupe Deville convertible.

Fagan: “Since I had to go over to where the car was and start it up and drive it a little every week, which I did, I decided this would be a good run for the car: LA to Frisco. Now I had room to take a few friends with me, and I invited my best friends; two decided to come along. One was a very close friend of mine named Frank ‘Chappy’ Chapman. The other was at the time my very best friend, Darryl DeLoach, former lead singer of Iron Butterfly. The ride up there was nothing but fun.”

The Benair brothers — along with a friend named David and Jonathan’s girlfriend Bonita — were considerably less fortunate on their trip up from their Panorama City base in Jonathan’s Ford Galaxy.

Benair: “As we were driving up the night before, a rock hit my brother’s gas line, and we had to stop in Tulare at about 5:30-6 in the morning and wait until 8 for a gas station to open that could repair the gas line on my brother’s car.”

Clic, who was 20 and living in San Jose, had a considerably shorter journey. Like his housemates — including his brother Carl and brothers Bill and Mike Davis (also all in their early 20s) — he’d moved to the West Coast from his native Hudson, Ohio, a then-small town roughly halfway between Cleveland and Akron. The concert fit the type of activity the four sought when they relocated.

ARRIVAL: THE UNEASINESS BEGINS

Owing to proximity, the four ex-Ohioans arrived early the morning of the show.

Clic: “We drove up there the day of, real early in the morning. And when we got there, there was like 10 billion cars, so we had to park miles away, because there was no real actual parking lot. There was just people parked on the side of the road, and you walked. We had to walk like a mile.”

Clic was already aggravated — “It was a long time, it was hot, and I was not happy that I had to walk that far” — and seeing the venue didn’t help matters. As opposed to the picturesque trees and grassy fields that reflected the bucolic splendor of Woodstock, Altamont was brown hillsides dotted with twisted metal, broken fences and the rusting remains of demolition derby cars.

Clic: “It was burned-out California desert, and it was all rundown. There was a lot of rickety old chain-link fence, and it was just a big fuckin’ dump.”

High on pot and LSD, the four settled down onto a blanket roughly 100 yards from the stage — occasionally swigging the water they brought along.

The Fagan party also had a good stash.

Fagan: “A couple of the other friends who I invited asked me: ‘Do you need any drugs for the trip?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’d sure like some mescaline or acid.’ These guys were dealers, and so they said, ‘Well, stop by the house here in Topanga and we’ll give you whatever you need for free.’”

Before Fagan could start getting high, he’d need to find a parking spot, which — thanks to arriving just before the show — proved quite difficult.

Fagan: “So we’re driving up the highway, and we see some people walking on the grass adjacent to the highway, and then as I continued driving, I saw more and more cars parked, and more and more hippies walking. Finally, it got to the point where there was only a rare parking space available — and these were all makeshift parking spaces. You know, there were no white lines painted, so I figured, ‘Well, I better take this one, because I don’t know if there’ll be another up ahead.’ Because the crowd that was walking got thicker and thicker. We figured the site of the concert must be just up ahead, so I parked and we started walking.”

Len Fagan (second from left) in Wichita Fall, 1968.

With Fagan’s unleashed German Shepherd Joe strutting beside them, Fagan, DeLoach and Chapman set off on the long walk to the venue. In an eerie foreshadowing of what would ultimately unfold, Joe repeatedly mixed it up with a Weimaraner as they walked to the festival. “He and Joe kept getting into it; every quarter- or half-mile, they’d get into a little altercation and I’d have to separate them,” Fagan recalled.

Following a lengthy jaunt that blistered Fagan’s feet, the three entered from behind the stage — only to discover that parking far away wasn’t their only concern.

Fagan: “We start walking out toward the audience, looking for a place for my two friends and my German shepherd and myself to sit crosslegged in the grass. Finally, I realize there is no more room here for us to sit. And I looked ahead of me, and I see there’s no room 100 yards back, either. [laughs]

“So I just said, ‘Fuck this,’ squeezed in-between two people with my dog, and then my friends are just a few yards behind me — and they take the opportunity to squeeze in there. The people immediately around us had to move inch by inch to their right or left so we’d have room, because I wasn’t going to settle for standing. And even if I stood, I’d be in people’s way. So we lucked out.”

They weren’t as lucky as the Benair party, who also entered from the back of the stage late thanks to their now-repaired Ford’s breakdown — settling up front, stage right.

THE CONCERT BEGINS

Chaos begat more chaos at Altamont: The stage, light towers and electrical wiring were hastily thrown together just hours before the festival started thanks to a change of venue from Sears Point Raceway to Altamont (and, before that, a failed attempt at getting permits for Golden Gate Park in San Francisco). As others have pointed out, it’s a miracle that nothing went wrong with any of the equipment. But that’s where the good fortune ended. Right after the first band, Santana, went on, the trouble started— and it would only get worse.

Fagan: “A big, huge, fat Mexican fellow took off all his clothes — and he was just a few yards to my left. And he started walking over people. Like I said, there was no room to walk in-between people; we were all so inched together so tightly. This guy takes off all his clothes, which was not a pleasant sight, and starts walking over people. And if I recall, you can see that happening in Gimme Shelter.

“It was pretty disgusting to have this guy naked walking all over you in your face. Even the Angels, no matter how rowdy and crazy they get, would never take their fuckin’ clothes off and walk over people. So that was beyond their permissiveness, I suppose. And when this Hispanic male first took off his clothes and started walking, I said to myself, loudly: ‘Oh, so this is the kind of day it’s going to be.’ And for the rest of the day, I did not forget that. I figured anything could happen here today; it’s every man for himself.”

Benair: “Very early on, there’s a very heavy, overweight guy who’s naked, and he starts screaming that he wants to play drums with Santana. I don’t know if it’s because he said that, because of his nudity, or a combination of whatever — the Hells Angels start beating him with pool cues. This is just frightening. So very early, there’s a lot of negative energy, and it’s very sporadic, but it’s very ugly.”

The fat man (who’s never been identified) was bloodied, and fighting continued during the next set by Jefferson Airplane, whose lead singer Marty Balin got pummeled in a failed attempt to stop the Angels from wailing on a concertgoer. Mick Jagger was also decked when he arrived after the Flying Burrito Brothers’ set — a scene that, according to Fagan, produced a loud, audible commotion from backstage.

“Huh,” Fagan said to himself, “this isn’t going to be Woodstock.”

Nonetheless, Fagan was duly impressed by the Burritos’ set.

Fagan: “I got very excited; I didn’t know they were playing that day, and they were one of my very favorites. So they come up onstage and they’re doing all this shit-kicker music, and boy was it great. To my taste, there isn’t enough of the Burrito Brothers’ performance on film in Gimme Shelter.”

Still, there’s more footage of the Burritos than of the next band, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — who don’t appear in the movie at all. If Fagan’s memory is correct, there may be a reason for that.

Fagan: “They made me sick. I never liked them. Believe me, their harmonies were an atrocity. They had these difficult three- and four-part harmonies, but they couldn’t deliver ’em in person, because on record, their voices were stacked, and it made them sound all sweet and full. Live, they were weak. So I had to sit through that.”

He also had to sit through a show that was rapidly spinning out of control. The beatings continued, drug casualties overwhelmed what little medical services were present, and crowd unrest grew. Under the influence of two tabs of mescaline, Fagan literally got a firsthand glimpse when — either during or shortly after the Flying Burrito Brothers’ set — he climbed one of the hastily assembled light towers.

Fagan: “I decided to climb up one and get a better view. So I get about maybe a third of the way up, maybe a little more like 40 percent up, and I’m saying, ‘Wow, this is great — what a view I’ve got! Why doesn’t everybody else climb up on these things?’”

No sooner did that thought cross Fagan’s mind then he heard shouting from the bottom of the light tower: “Hey you! You!”

“What is this? Who are they yelling at?” Fagan thought to himself after cursorily scanning the surrounding area.

Fagan picks up the story: “And then I take another look, and right at the bottom of the trust was a guy — remember, I’m on a lot of mescaline that day — that in my mind looked like a dangerous pirate. I don’t know if he had an eyepatch and teeth missing and a bandana around his head, but that’s what I saw and felt. I could have been hallucinating — who knows?”

The shouting persisted: “Hey you!” This time, Fagan looked straight down and met eyes with the shouter. “Yeah you! Get down off of there.” But a confused Fagan didn’t move.

“Hey you! Yeah, you! Somebody back there wants you down,” the shouter said, pointing to a bus roughly 45 degrees to Fagan’s right.

Fagan: “There is this big yellow school bus there with lots of Hells Angels sitting on the top, misbehaving, giving out very bad vibes. He says, ‘No, those people want you down.’ Then I said, ‘Oh … OK.’ I slowly climbed down the trust, and my faithful dog Joe is right at the bottom, waiting for me.”

The canine wasn’t the only sight to greet Fagan, who now stood under the blank, menacing glare of the Hells Angel who’d ordered him to come down.

Showing little emotion, the biker’s eyes quickly darted to Joe before refocusing on his owner. “Mean, huh?” the Angel queried.

Fagan: “Joe was far from mean, but I shook my head and said, ‘Oh yeah.’ [laughs]”

Further back in the crowd, at least several concertgoers were also growing weary of tower climbers like Fagan.

Clic: “People were doing crazy shit all day. They were climbing up on the stanchions, and so they’d be announcing from the stage: ‘We’re not going to play, no more bands are going to play until you get down off of those things. We don’t have insurance.’ The whole day was like that.

“It just seemed like there was some sort of tension going on throughout the crowd. You could feel that even from as far back as we were.”

Reasons for the tension, however, were unclear to those in the back. Other than learning about Balin’s mishap thanks to Paul Kantner confronting the Hells Angels onstage (a scene captured in Gimme Shelter), Clic said his group had no inkling of what was really going on: “Because we were so far back, the only trouble that we had noticed was when the Jefferson Airplane were playing during the day.”

WELL, YOU HEARD ABOUT THE …

Having learned of all the day’s drama and violence upon their arrival by helicopter, the Grateful Dead — who’d been pivotal in setting the show up — elected not to play. In place of the Dead’s long set came a 75-minute wait that only made things worse.

Fagan: “I can’t speak for 300,000 other people, but I know I felt very uncomfortable during the long wait for the Stones, because I knew that anything could still happen here.

“In-between bands, there was a very uneasy feeling that day. I recall saying to myself, ‘This is the most ominous day I’ve ever experienced.’ The vibes were just not good vibes, and I believe they were all stemming from the Hells Angels. And sometime during the day, we found out that there was no real security there. I figured guys from the FBI or something would be there to keep things OK, but to my knowledge there were no real authorized police there that day. So the Hells Angels could get away with anything they wanted to, and we knew it. I thought it was very sad that there were 300,000 of us and maybe 50 of them, and we couldn’t handle ourselves.”

Clic: “It wasn’t run very well. It was just this slapped up thing and the bands were kind of willy-nilly. By the time the Stones got on, it was really late at night.”

Finally, as night fell on Northern California, the Rolling Stones took the makeshift stage. Darkness descended on more than just the sky, as the already volatile situation throttled uncontrollably to its sick apex of further beatings, trampling and, ultimately, a murder. Benair, right in the thick of it, cited a Hells Angel’s bike getting knocked over as a flashpoint.

Benair: “I fell down and people started trampling me — and my brother pulled me up. So obviously, we moved at that point. About halfway through the set, we go back to the side, and because I’m so young, I jump on the back of the stage and I stand on Keith’s or Mick Taylor’s amp line. I’m back there and nobody bothers me because I’m young. My brother gets up there and a Hells Angel tells him to get off the stage, so he set up on the side. So I watched the last quarter of the set from the stage. Absolutely no one even gave me a dirty look, because I’m just too little. Even the Hells Angels weren’t going to bother with a little kid.”

Fagan: “They waited till it got pitch black, then they turned the lights on onstage, and then soon after they took the stage and started playing. But I thought that was very foolish of them and selfish to make a crowd like that wait for so long to go on.”

Nonetheless, Fagan enjoyed the set: “Boy, were they in form that day. They were playing everything on the back of the beat, if you know what I mean; none of their songs were runaway rollercoasters like some of them were on their early records. They played so nasty; the feel they had that day was so nasty, then they start ‘Midnight Rambler’ and Mick Jagger is playing with the audience.”

“Things really, really reached their peak with the Stones, because they were playing with us. They were instigating and playing with the audience, trying to get any kind of reaction they could out of us. And they did a great job of it.”

From further back, however, there was only the music to go on — making the interruptions to the Stones’ set all the more exasperating.

Clic: “The Stones had to stop in the middle of songs, and bands never do that. Whatever ruckus was going on up front was evidently playing out right in front of them, and we were so far back and it was nighttime that we were going: ‘C’mon, just fucking play. Sit down up there.’ We were just annoyed at the crowd.”

CONFUSION AND DISORIENTATION

And then, the Stones finished — albeit not quite as triumphantly as they intended, leaving the speedway in an overcrowded helicopter as 300,000 mostly stoned and drunk concertgoers attempted to find their way out in near-total darkness. Before departing, however, Benair — still standing on the stage — sensed an opportunity.

Benair: “When the show’s coming to an end, I look over at Charlie Watts — and at that point, I had just gotten a drum set. And Charlie had a crushed velvet jacket next to his floor tom, and I went over and tapped him and said, ‘Charlie, can I have your drum sticks?’ And he said, ‘yeah,’ and he gave them to me. It was something brazen I did at the moment, and I still have them.”

Other attendees’ exits were decidedly less interesting. Between the delays, false starts, disorganization, and not eating all day (Altamont offered no concessions), the four Ohioans — now coming down from drug highs — had had enough. Actually, it now just three: Bill Davis had disappeared into the crowd. His friends would have to find him later.

Clic: “We were like: ‘Let’s get the hell out of here and get to McDonald’s or something.’ And Altamont Speedway’s out in the middle of nowhere.”

Fortunately, and perhaps owing to its colorful psychedelic paint job, the three were able to find the 1965 Plymouth Valiant that got them there.

Clic: “Between all of us, we remembered where it was, but it didn’t matter, because you couldn’t move. Everybody got into their cars at about the same time, and started and tried to go, and you just have to leave single file. It took forever, and we were not in any good mood.”

But that was nothing compared to what Fagan, DeLoach and Chapman faced: They were still high, and had no idea where the Caddy was.

Fagan: “We didn’t know which way to go. And even if we knew which way to go, we didn’t know how far to go. So a god shot happened, and I run into a friend of mine named Dale, who was a friend from high school. And I asked him, ‘Could you please give us a ride back to our car?’ He said ‘sure.’

“Without that, man, I don’t know what would have happened to us. We start driving back along the highway where thousands and thousands and thousands of cars were parked. In fact, about a half-mile or so before the site of the concert, cars are not only parking on the side of highway, but they’re parking in the right lane of the highway — right on the highway. It’s like they just abandoned their cars and walked to the show, which I found fascinating. I would never do something like that, man. That’s dangerous.

“I don’t know if this is accurate or not, but I seem to remember finding the car in the early daylight. We’re driving down the highway that we walked up to the show on, and there’s the Cadillac sitting there, all by itself — like we were the last ones to get back.”

A glance at his friend’s odometer gave Fagan an even bigger shock: They’d parked 14 miles from the site.

Fagan: “After the show, we were certainly in no condition to walk 14 miles. So that’s why I call that a god shot.”

Compared with Fagan and Clic, Benair — tagging along with three elders — got off easier: “Because we parked behind the stage, we got to our car much quicker than most people. Getting out took a long time for everybody.”

Though Fagan had heard rumors of the Hunter murder at the end of the show, Benair and Clic (like most attendees) didn’t find out until the next day — adding to the drama of an already unsettling experience.

Benair: “Having been in bands, having seen 2 trillion concerts, I can say I’ve never been to anything even remotely close to that in terms of just the negative energy that you could have cut with a knife. It was just alarming. You know, I’ve been to shows where there’s definitely some bad vibes coming from the room, but nothing even close to that. It was one of those things where being so up close and personal made it even weirder because if I’d been far away, I would have just experienced this little dot of music — and I may not have even felt the energy was negative, other than the Stones saying stuff.”

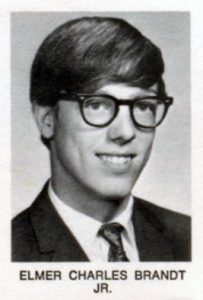

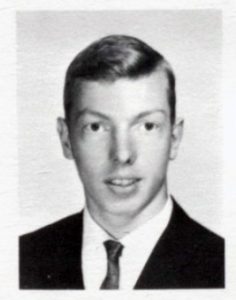

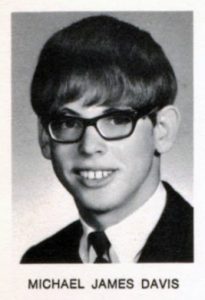

Jonathan Benair (center in glasses) at Altamont.

Clic: “We were reasonably satisfied that we saw those bands for free, but at the same time, it was a long day and it wasn’t a groovy trip. The whole day was just a bummer.”

In the aftermath, Jonathan Benair would appear prominently in a photo of Rolling Stone’s coverage of the event. Sadly, he passed away in 1998.

BACK TO ALTAMONT

Buzz, Carl and Mike Davis (who died sometime in the ’80s) were finally back in San Jose by the wee hours of December 7, but their business was not finished: They had to find Bill. And the only place to start the search was back where they last saw him: the now controversial Altamont Speedway.

Clic: “One by one, everyone went looking for Bill. And what ended up happening is Bill had stayed at Altamont and had started cleaning up — just being part of the cleanup crew. And so we ended up going back there and found him, and we were about out of options anyway at the place — because we didn’t have enough money to pay for the next month’s rent. So we ended up staying at Altamont, and we’d go out everyday under the guise of cleaning up.

“People had just left everything; it was just blankets and bottles and junk everywhere. But there was an unlimited amount of free drugs; there were probably about 20 people there, and we were staying above the stands in a press box. We were sleeping on the floor in there, and going out in the daytime and picking up crap. And then we’d come back and everybody would kind of throw whatever drugs they’d found on the table, divvy it up between us, and get high.”

Soon, the four met Altamont owner Dick Carter (who has a cameo in Gimme Shelter) — finding further employment at his San Leandro body shop once the racetrack was cleaned up.

Clic: “We spent about two weeks, maybe longer, cleaning up the place. By that time, we met Dick Carter, and we knew a lot about cars and hot rods, so we talked to him. He picked up that we knew stuff about cars and that he could use us. So that’s how we ended up going to his hot rod shop, then we just moved on from there.

“We ended up moving into the back of his body shop. He had race cars back there — Mustang GT 350s and everything. So we were sleeping on the floor back there, but we’d work for him. He had a pool in his backyard that was all trashed out, and we cleaned it all up. And he had a couple of friends along the same road that his hot rod shop was on; there were used car lots all over the place. So when we weren’t working for him, we could walk down to the car lot guys — and there’d be twenty or thirty cars there in the used car lots, and we’d wash cars.”

It was enough to keep them busy, but it wasn’t quite the idyllic California life Clic had envisioned. Tired of the hippie lifestyle, he cut his hair, moved back to Hudson and got a real job that allowed him to purchase his first guitar in early 1970. So at least in one case, Altamont had a positive effect.

The photos of Carl Brandt and Bill Davis are from the 1965 Hudson High School yearbook, while the photos of Mike Davis and Elmer Charles Brandt Jr (aka, Buzz Clic) are from the 1967 yearbook.