-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers -

OISTER – 1973-74 (Hozac) 2-LP

Heaven-sent for fans of classic ‘70s pop, this is the first ever release by the legendary Tulsa outfit comprising Dwight Twilley and Phil Seymour who would soon thereafter become the great Dwight Twilley band. The Twilley band were a unique hybrid of harmonic Anglophile pop/rock and rockabilly who released two brilliant albums on Shelter—one very polished, one much earthier—before the two principals went solo. Oister was the same but different. The differences may come down to recording technique or simply the youth of our heroes.

There is a charming fragility and innocence here not found in the later Twilley or Seymour stuff. And a dreaminess: indeed much of this is the embodiment of the term ‘dream pop’ and should appeal to a whole host of people who find the concept of power pop anathema. And the current crop of Big Star fans. The lo-fi aspect will also appeal to fans of DIY. There’s a little bit of the baroque but for the most part it’s spirited, minimalist early Beatles/Hollies-style pop rock, with a rootsiness learned from early mentor and former Sun artist Ray Harris, and the frequent prominence of Twilley’s piano lets you know it’s the ‘70s. Most of the songs here were later rerecorded for official release, including the sublime “You Were So Warm,” but even a lot of the re-recordings have only appeared on Twilley rarities collections, and the versions are strikingly different. The material is uniformly strong; the never-before-released “Pop Bottle” is a stunner.

Thank god for the current power pop revival and Hozac for this release: hopefully it will lead to a wider appreciation of Dwight and Phil and all their recordings. Now can someone put it out on CD for me please? (David Laing)

Col. Bruce Hampton (1947-2017)

By Alan Bisbort

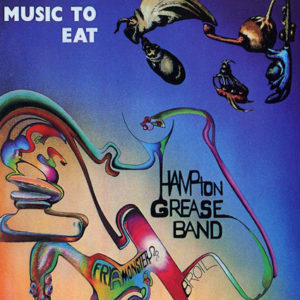

The first time I saw Bruce Hampton, he was standing on the tiny stage at a suburban Atlanta “teen scene” venue reading the contents off the side of can of spray paint. This was in 1968. A sweaty, short-haired guy in a button-down-collared shirt with the build of a middle linebacker, Hampton looked out of place accompanied by two guitarists, a bassist and drummer all with hair so long you could not see their faces and all of whom were playing as loud as fire engine sirens. Needless to add, I had never seen anything like it in my 15 years on this planet. Nor had the handful of other brave teens whose parents had dropped them off at the alcohol-free club in the shopping mall. A much larger crowd of teenyboppers were milling about in the parking lot outside, having been driven from the room by the psychedelic noise created by the Hampton Grease Band. Years later I learned this was just one of the many ill-advised gigs the band’s manager had secured for them prior to their signing a record deal with Columbia, which released their one and only album, the epic double-LP package Music to Eat. (On which was a cut called “Spray Paint”).

Not too long after that, the band—Hampton on vocals and dada vibes, guitarists Harold Kelling and Glenn Phillips, bassist Mike Holbrook and drummer Jerry Fields—began appearing at free shows in Piedmont Park, the downtown Atlanta hangout for hippies, druggies, bikers and most of the runaways in the southeastern US. Soon enough, on the strength of these monumental free gigs, the Hampton Grease Band would wow hundreds of thousands of “freaks” at the two Atlanta Pop Festivals and regularly share bills with Jimi Hendrix, the Allman Brothers Band, Grateful Dead and even Captain Beefheart & his Magic Band. Bruce was, in fact, a Southern-fried version of Don Van Vliet, with a warming touch of Sun Ra. To my fragile eggshell mind, Hampton, and his band, provided an epiphany of sorts—showing me that music could go beyond mere recitation of clichéd boogie lyrics and shoddy playing and take you to places you never expected to go.

The Hampton Grease Band carried on for a few years, then members drifted off to pursue their own musical muses. Phillips and Kelling went on to form their own bands (a live recording by Phillips’ band was favorably reviewed in UT #44). Over the next four decades, Hampton added the honorific “Colonel” to his name and recorded a few solo albums (including the unsurpassably strange One Ruined Life of a Bronze Tourist) and became a major force in the jam band subculture that flourished under the banner of H.O.R.D.E. He fronted several bands of his own, including the Aquarium Rescue Unit, Fiji Mariners and Codetalkers, and served as a mentor to many young, gifted players who’ve since gone on to productive musical careers.

In the 1990s, during one of his passes through Washington DC, where I then lived, Hampton contacted me through a mutual friend and I spent a day museum-hopping with Bruce and members of his band, one of the highlights of my 17 years in the nation’s capital. He was generous, funny, kind and subject to conversational turns on a dime. No wonder Billy Bob Thornton called Hampton (who appeared in his film Sling Blade) “the eighth wonder of the world.” Listening to Hampton on album (other than the indispensable Music to Eat) was not quite the same as seeing him live. I once saw him play a gig with a golf club in his hands, practicing his swing while his band jammed, and every so often going to the microphone to pronounce the word “hose.” Every concert was different, unpredictable, strange and beautiful.

Early in May, a veritable who’s who of Southern rock gathered for a sold-out 70th birthday celebration for Col. Bruce Hampton at Atlanta’s historic Fox Theater. At the end of the show, during the final encore (of “Turn on Your Lovelight”), Hampton collapsed on stage and died minutes later at a nearby hospital. The mourning could be heard all the way to New England, where I live now. Both of my sisters, who live in Atlanta, called to bring me the news, then high school friends I hadn’t heard from in years began contacting me. Eventually, the strangeness of Col. Hampton’s demise gave the story “legs” in print and on the Internet, propelling it even into the staid pages of the Wall Street Journal—providing Hampton more notoriety in death than he ever had in life. The consensus seems to be that he could not have had a more fitting exit, dying on stage like that.

For me, though, it’s just sad. Part of it is, no doubt, tied up with losing that personal connection to my youth, but so many musicians I admired have died before this and the sadness didn’t linger like this. With Hampton’s death, it’s as if a musical force were shut off, like a faucet or a hose. I had no delusions that he still had some musical masterpieces locked inside his fertile cranium. No, it’s clear now that HE was the masterpiece.

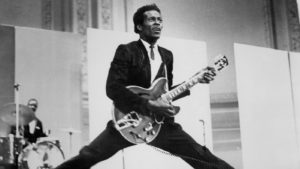

One Dozen Picked Berries: 12 Great Chuck Berry Covers

By Doug Sheppard

The musical, cultural and societal waves that Chuck Berry made by pioneering rock ’n’ roll could fill a book. And of course, there are so many great songs—brilliantly executed, simple yet evocative vignettes that in turn provided inspiration and cover fodder for countless bands down the road. As we mark his passing, the time is right to revisit the best Berry covers.

Lists like this tend to be a few obvious choices coupled with an avant-garde rendition and/or an unexpected version by an artist (usually a pop crooner) to prove how great the song is. I’m sure there’s a stunning Chinese Sanskrit version of “Johnny B Goode” played on exotic instruments and probably even a reggae remake of “Jo Jo Gunne,” but I don’t care. To me, it’s all about the rock ’n’ roll. Rather than researching, I listed the first 12 that popped into my head; after all, if a song isn’t memorable, then how good is it?

As the list emerged, so did a theme: The greatest Berry covers tend to be spontaneous, or at least remade in the spirit of fun—much like Chuck’s originals. Maybe I missed something. Maybe I didn’t. Is this list definitive? At least in your mind if you want it to be.

1) THE MC5: “Back in the USA” (1970)

The trebly highs, lack of bass and neutered guitars of Jon Landau’s botch-job production nearly ruined Back in the USA, but it’s a great album nonetheless—and the Berry cover seems to make the perfect title track. With the Five having fought the law, the record company, Hudson’s and society in general, one can’t help but note the irony when Rob Tyner sings “I’m so glad I’m living in the USA” followed by the more emphatic “I’m so glad I’m living in the USA.” Sarcastic or not, the insistent background vocals, wind-chime piano and ripping guitar solos imply a good time. “Detroit, Chicago, Chattanooga, Baton Rouge” indeed.

2) THE CHOCOLATE WATCHBAND: “Come On” (1967)

The Chocolate Watchband had a way with covers, besting the Tongues of Truth on “Let’s Talk About Girls” and the Brogues with “I Ain’t No Miracle Worker,” possibly even the Kinks with “I’m Not Like Everybody Else.” Another fine moment was “Come On,” likely inspired by the Rolling Stones’ version from four years earlier. But whereas the Stones’ take moves like an English sports car, buzzing adroitly like an Aston Martin, the Watchband remake ups the tempo and speeds smoothly like a ’66 Corvette, pulsed by Gary Andrijasevich’s drumming and the deadly harp/vocal whammy of Dave Aguilar.

3) LONNIE MACK: “Memphis” (1963)

From Cincinnati by way of rural Indiana, Lonnie Mack turned “Memphis, Tennessee” into a melodic marvel on this instrumental remake that landed him his first hit in 1963. Mack’s fluidity on the Flying V is infectious and, even more remarkably, this was recorded as an afterthought when he had 20 minutes of studio time remaining from a session he’d played on.

4) JOHNNY WINTER: “Thirty Days” (alternate version) (1974)

Don’t you hate it when lists have some obscure demo version of a song available only on an obscure album? So do I, but there’s no way around it in this case. The Johnny Winter version of “Thirty Days” that ended up on Saints & Sinners is good, but it can’t compare to this alternate. This version, which appeared on Legacy’s A Rock ’n’ Roll Collection in 1994, rips with Johnny’s badass vocals, trademark white-lightning guitar solos and a rough rhythm section. Sounds like an on-the-spot first take, which may be why it initially didn’t come out.

5) DAVE EDMUNDS: “Promised Land” (1971)

Dave Edmunds took one look at the emergent studio sophistication of the ’70s and responded with Rockpile, an album flaunting simplicity in sound and production—including this killer Berry cover drenched in reverb and Dave’s verve for primal rock ’n’ roll.

6) THE ROLLING STONES: “Around and Around” (1964)

The Stones’ love of Berry is well-known, from the faithful remake of “You Can’t Catch Me” on Now! to the Altamont-era live renderings of “Carol” and “Little Queenie.” But the pinnacle of their Chuck fetish was this killer romp from Five By Five and 12X5. In hindsight, one can hear how they were on the verge of parlaying their Berry and Chess blues fandom into something entirely their own.

7) THE YARDBIRDS: “Jeff’s Boogie” (1966)

Credited to Jeff Beck as an “original,” but we all know that this was “Guitar Boogie” retitled, right? Jeff’s licks are at the forefront, but don’t underestimate drummer Jim McCarty’s swinging beat, which makes the engine purr.

8) MOUNTAIN: “Roll Over Beethoven” (Flowers of Evil live version) (1971)

Sidelong tracks rarely work, but “Dream Sequence”—side two of 1971’s Flowers of Evil—is one of them, mainly because it’s several songs strung together rather than a long jam. As Corky Laing and Felix Pappalardi drive harder than a Mack truck on the Long Island Expressway, Leslie West piles up guitar riffage and fireworks, including a heavier than heavy “Roll Over Beethoven” that shreds ELO’s version like a lawnmower over grass. (Legacy later isolated “Roll Over Beethoven” as a single track for 1995’s Over the Top double-CD compilation.)

9) THE BEATLES: “I’m Talking About You” (1963)

While some are partial to studio creations like “Rock and Roll Music” and “Roll Over Beethoven,” to me the Fab Four’s best stab at Berry was a 1963 BBC Saturday Club rendition of “I’m Talking About You.” With one foot in their raw Hamburg past and the other in their British invading future, this R&B-soaked stomper (found on On Air — Live at the BBC Volume 2) should put to rest any notions that the Beatles were tame.

10) THE FLAMIN’ GROOVIES: “Carol” (1970)

The flame of rock ’n’ roll may have flickered and dimmed in the early 1970s, but its spirit lived in the Flamin’ Groovies, who did a bang-up job on Berry with this Matrix rehearsal. “Carol” represents everything that made the early Groovies great: Roy Loney’s rockabilly-esque vocals, piston-popping rapid-fire guitars by Cyril Jordan and Tim Lynch and the tribal pound of Danny Mihm and George Alexander.

11) THE WALKING FLOUR: “I Want to Be Your Driver” (1967)

Hundreds if not thousands of American teens covered Chuck in the garage band era, but none were as forthright as this short-lived Sacramento, California quintet. “I Want to Be Your Driver” stands out not only because it’s a lesser-known Berry side, but with red-on-the meter fuzz, organ and spasmodic Ringo-like drumming by a guy who would later play with Les Dudek. Initially unreleased but unearthed on Ace/Big Beat’s The Sound of Young Sacramento in 2000.

12) PAUL REVERE & THE RAIDERS: “Maybellene” (1964)

Also initially unreleased but far from obscure, this live rendition illustrates the flair that so many early ’60s Northwest bands (the Sonics’ version of “Roll Over Beethoven” also comes to mind) had for cover material. After an irreverent joke about Chuck’s brushes with the law, the Raiders kick in to a rearranged version of “Maybellene” that sets it to a “Memphis”-like swinging beat in lieu of the original’s two-step rhythm.