-

Featured News

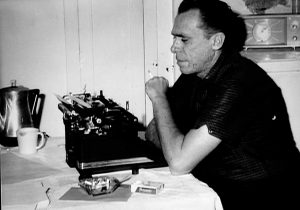

Shel Talmy: August 11, 1937 – November 14, 2024

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

The Ventures’ first Documentary: Stars on Guitars

By Harvey Kubernik

The first-ever full length documentary chronicling the 60 year career of the Ventures, The Ventures: Stars on Guitars, debuted on DVD, Blu-ray and VOD to cable providers and streaming platforms on December 8, 2020 via Vision Films Inc.

Outlets for viewing include iTunes, Vimeo, Comcast, Spectrum, DirecTV, and Amazon. There might be a sense of wonder about how these platforms have emerged from times when TV was a luxury and now can be watched on a mobile phone. It can be traced by understanding the history of cable TV and how it helped millions of artists worldwide. Similarly, it’s the definitive history of the instrumental rock ‘n’ roll band from director Staci Layne Wilson, daughter of the Ventures’ founder Don Wilson and features 35 interview subjects. The filmic journey is told from the point of view of Wilson, the last original member of the band.

The Ventures are the bestselling instrumental rock group in history. The group has sold over 100 million records with nearly 300 different retail releases in the US and worldwide since beginning with “Walk, Don’t Run.”

The Ventures’ classic quartet lineup consisted of rhythm guitarist Wilson, bassist Bob Bogle, initially lead guitarist, Nokie Edwards, lead guitar, converted from bass, and drummer Mel Taylor. The Ventures were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2008.

It was on a construction site in Seattle, Washington, in 1959 that two guitarists, Don Wilson and Bob Bogle, decided to perform together at local sock hops, initially as the Versatones. They added a rhythm section and then became the Impacts for a very short period. Finally settling on the name “The Ventures,” they recorded two songs that Don’s mother Josie released on her Blue Horizon Records label.

The Ventures self-pressed a second single, a cover of Johnny Smith’s “Walk, Don’t Run,” a song that Don and Bob had discovered on a Chet Atkins album. “Walk, Don’t Run” was a hit single in 1960, reaching Number 2, just behind Elvis Presley’s “It’s Now or Never,” and over the last forty-six years, Wilson and his partner Bogle have subsequently recorded 250 albums and sold 100 million records, 50 million of them just in Japan.

Chris Hillman’s Time Between: My Life as a Byrd, Burrito Brother, and Beyond Autobiography Due

By Harvey Kubernik

CHRIS HILLMAN is arguably the primary architect of what’s come to be known as country rock. On November 17, 2020 BMG Books will publish his autobiography Time Between: My Life as a Byrd, Burrito Brother, and Beyond. Dwight Yoakum penned the foreword for the 315 page volume.

2021 dates are being planned for Hillman’s live show Time Between: An Evening of Stories and Songs, featuring John Jorgenson and Herb Pedersen, a night of songs and stories that dovetails with this memoir.

In 2013 I spoke with Chris at the same venue when photographer Guy Webster mounted an exhibition and comically pleaded once more that it was time for Chris to tell us his musical life story. When I last talked to Chris on the 2018 Sweetheart of the Rodeo Los Angeles tour date backstage at The Ace Hotel with Roger McGuinn and Marty Stuart and his band the Fabulous Superlatives, he assured me he was going to do his autobiography. That night guitarist Mike Campbell of Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers came up on stage and played on a few numbers with Roger, Chris and Marty’s band. A couple of decades ago I remember when Mike Campbell came into the CD Trader record store in Tarzana, California and bought a rare Byrds European picture sleeve EP. More than once in my encounters and interviews with Tom Petty he praised McGuinn covering “American Girl” and was thankful he and his band the Heartbreakers had an opening slot in March 1977 when Roger headlined the Bottom Line club in New York.

Hillman was born in Los Angeles in 1944. His early years were spent in San Diego County. Chris’ late fifties and early sixties television diet were the Southern California country music shows Town Hall Party, Cal’s Corral and The Spade Cooley Show. In 1959 he saw the famed bluegrass band the Kentucky Colonels at The Ash Grove club on Melrose Avenue in West Hollywood. He soon took up the mandolin and became a fixture in the San Diego folk music community playing coffee houses. Hillman’s first band was the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers.

In 1963 he joined the Golden State Boys, an outfit that showcased Vern Gosdin, his brother Rex and Don Parmley. They evolved into the Hillmen, and Chris later did a brief stint with the Green Grass Revival. Chris was in the annual Santa Claus Lane Parade on Hollywood Boulevard on a float with guitarist and record producer Speedy West, who was the first country steel player to employ a pedal guitar built by Paul Bigsby.

It was the Hillmen’s record producer and manager, Jim Dickson who in October 1964 introduced Chris to musicians and songwriters Jim McGuinn, David Crosby, and Gene Clark, developing their sound in the Jet Set and then the Beefeaters. Mandolin player Hillman joined the group, was converted to bass and the addition of drummer Michael Clarke. They became the Byrds on their folk, rock, psychedelic, country, and pop 1965-1967 recordings and tours.

Chris was a fixture in Laurel Canyon during 1965-1968 before relocating to Topanga Canyon in ‘68. In April 1966 he was instrumental in securing Buffalo Springfield their first ever booking at the Whisky A Go Go. During 1966, the house Hillman was renting in Laurel Canyon burned down. The local NBC-TV affiliate broadcast the incident. It was a loss the entire community felt at the time.

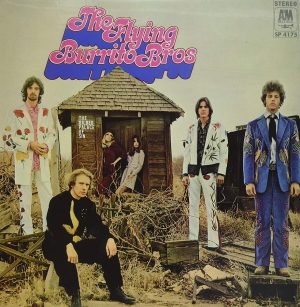

Hillman went on to partner with Gram Parsons to launch the Flying Burrito Brothers, recording a handful of albums that have become touchstones of rock-influenced country.

Following his tenure with the Flying Burrito Brothers, Hillman then embarked on a prolific recording career in various configurations: as a member of Stephen Stills’ Manassas; as a member of Souther-Hillman-Furay with JD Souther and Richie Furay of Buffalo Springfield; as a solo artist; and in a trio with his fellow former Byrds Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark.

In the 1980s, Hillman launched a successful mainstream country career when he formed the Desert Rose Band with Herb Pedersen and John Jorgenson, scoring eight Top 10 country hits. In the midst of his country success he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of the Byrds. Hillman also released a number of solo albums with the most recent, Bidin’ My Time, produced by Tom Petty.

In Time Between, Hillman takes readers behind the curtain of his quintessentially Southern Californian musical journey.

I’ve seen Chris Hillman in a slew of bands over the last 55 years from the Byrds to Flying Burrito Brothers to Manassas to the Desert Rose Band and a handful of dates this century he did with Herb Pedersen. In 1988 I worked on the benefit for The Ash Grove held at the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles where the original five members of the Byrds appeared.

This decade I asked a handful of friends, writers, photographers, filmmakers, musicians, deejays and Hillman’s bandmate Roger McGuinn to comment on the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, followed by my own 2007, 2010 and 2014 interviews with Chris.

The Scottsville Squirrel Barkers. Chris Hillman bottom left.

Chris Darrow: I first met Chris Hillman in 1963 at Disneyland when he was in the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and I was in the Floggs.

In 1965 my [then] wife Donna and I were sitting watching TV one night and we turned on the Hullabaloo TV show. It was great program and we all waited for it because there was little rock and roll on TV. All of a sudden there was a sound that permeated the airwaves, a jangly 12-string guitar lick and a close up of a guy [then Jim McGuinn] in small dark glasses and a Beatle haircut. I said, “It’s that guy that Richard Greene brought to our gig?”

As the camera panned the band, I caught a glimpse of another familiar face, Chris Hillman, but instead of his short curly hair and Levis and T-shirts, he was wearing Beatle boots, pegged pants and had a long, straight, bobbed haircut. “This is Chris’s new band, I guess,” I said to Donna. It was the introduction of “Mr Tambourine Man” and it was, of course, the Byrds. Now there were people who we knew who were in big bands and it looked like something we could all do.

Jim Dickson: When Bob Dylan came to the Monterey Folk Festival, 1963 or ’64, I went over to a room with Victor Maymudes and some other people and Dylan had a whole bunch of new songs and he sat there and played them all. Him and the guitar. And that’s what blew my mind. He had one great song after another. He was playing them live.

It was the first time I met Dylan. The songs became alive in front of me and they were all new songs that weren’t on his first album. He sang about 20 songs and I was just glued to them. I never heard anybody write like that. He was just playing one song right after another. And they were amazing.

When I heard “Mr Tambourine Man” I said, “That’s the best. That could be a hit song.” Artie Mogull was involved in Dylan’s publishing just gave me the song. And I put my head down and went after that one with the Byrds. They already had about a couple of dozen songs that Gene Clark wrote and a couple of (Jim) McGuinn, and all those songs. And I didn’t hear a hit in any of it. But there was a quality we were getting. And I put “Mr Tambourine Man” in there and we recorded it. And, David got it kicked out for a while.

What happened was David campaigned against it. He talked Gene Clark out of singing it. Saying to Gene, “Your songs are better.” Of course he didn’t like Gene’s songs. “Your songs are better than that.” Gene was the lead singer for the Byrds. So when Gene said he wasn’t gonna do it, based on Crosby’s influence, McGuinn volunteered. And I said, “OK. Let’s give it a try.” And McGuinn created a voice I had never heard before. He tried to come down somewhere between Dylan and (John) Lennon vocally. And it worked. I could hear it on the Byrds’ Pre-Flyte tape that I produced. He was getting the song and it was working and all I needed was the right music behind it and I would have a hit.

And when Crosby had it kicked out of the lineup at rehearsal, Dylan showed up in town and wanted to come to the World Pacific studio. So I told the band Dylan was coming and please do “Mr Tambourine Man” again for him.

Here’s Dylan, at World Pacific. He came to the studio more than once. One time with Bob Neuwirth, who played a key role. McGuinn took it over. Dylan also sat there and played the piano with them, got to know them a little bit. Michael Clarke was still playing on cardboard boxes with a tambourine on top. He didn’t have his drums. McGuinn had a 12-string acoustic guitar with a pick up and Dylan walked around listening to what each person was playing, all that sort of stuff. They were so right and he thought they were really charming.

Then I sent the record to Dylan, we had to get his OK. That’s where Bobby Neuwirth comes in. Dylan and Neuwirth sat on the floor and they wore out the first acetate I sent ‘em. And they listened to it over and over and that’s when Neuwirth said, “You can dance to it.” And [manager] Albert Grossman was trying to talk him out of it.

Dylan and Grossman had the finished product but Neuwirth was able to persuade Dylan, “Hey man, it’s a rock ‘n’ roll band playing one of your songs.” And going up against Albert was not comfortable for him, but he OK’d it and we were able to release it. I later got the approval for a photo I took of Dylan and the Byrds at Ciro’s that was on the back cover of the first Byrds’ LP.

The Byrds first heard “Mr Tambourine Man” all together on the radio station KFWB. When they were in a car, a station wagon they bought from Odetta. They had to pull over.

And David, who had been anti-Dylan all along, the next time we went to Ciro’s, I see him outside on the sidewalk out front, explaining to some young girl the deep meaning of Dylan and all that stuff. Like he was the expert…

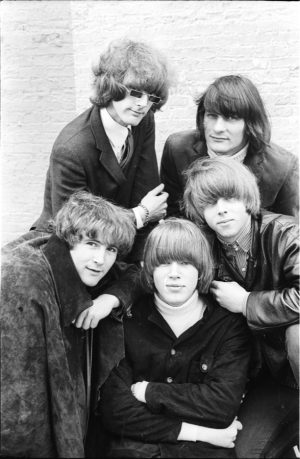

The Byrds, 1965.( Photo by Jim Dickson, Courtesy of the Henry Diltz Archives)

David Kessel: My dad Barney Kessel played rhythm guitar on a “Mr Tambourine Man” session at Columbia Studios on Sunset Boulevard. Chris Hillman mentioned Barney on the date in a book Turn! Turn!Turn!: The ‘60s Folk-Rock Revolution. Hal Blaine, Leon Russell, Joe Osborn and other cats were booked with Roger McGuinn, David Crosby and Gene Clark.

The Byrds came out during the electrification of folk music. This was cool to me, because they had a new vibration that was being felt by others. They also had nice harmonies on the vocals. It was at the beginning of the San Francisco/ LA Sunset Strip Hippie thing.

Herb Pedersen: Chris, in the Byrds was playing the bass like a rhythm guitar, using a flat pick. He comes from the mandolin, so it made perfect sense for him to play with a pick and not his fingers. Chris was more of a solid, no-nonsense kind of bass player that brought a lot of feel and good direction to what he was doing.

Andrew Solt: Discovering the Byrds in the summer of 1965 was a life changer. Dancing to the Byrds’ jet-powered rock at Ciro’s on Sunset Strip had me feeling like I was present at America’s version of the Cavern in Liverpool. After graduating Hollywood High School in the winter of 1964, end of January ’65, after the weekend, I started UCLA in February ’65. And Ciro’s was two blocks from where I lived. Mecca!

Rodney Bingenheimer: In 1965 I stood outside the Peppermint Stick nightclub in San Francisco, North Beach and heard the Byrds. I was underage. Later in 1965 I moved to Hollywood and was at The Big TNT Show where they played in the Moulin Rouge with Ray Charles, Joan Baez, Donovan, Bo Diddley, Roger Miller, Lovin’ Spoonful, the Ronettes, Petula Clark, and the Ike & Tina Turner Revue. It was Godhead! Because of the sound system, the guitars, amps, drums and Chris’s bass playing, the Byrds were really making folk music come to life.

Chris Hillman was always the quietest rock star and a nice guy. I saw him at Ben Frank’s on Sunset Boulevard around the time I met Bob Dylan at The Trip which was across the street.

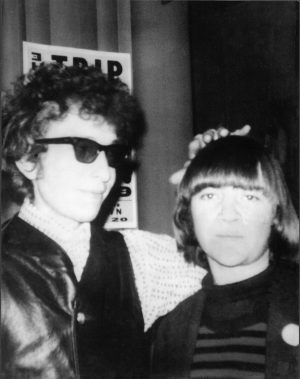

Bob Dylan and Rodney Bingenheimer at The Trip, 1966.

Dr James Cushing: The Byrds hit the scene when I was twelve, living in the East, and primed for the New Thing by the Beatles and the Stones. Over the AM radio (WABC was my go-to station, with Dan Ingram and Cousin Brucie), “Mr Tambourine Man” sounded like nothing else ever, the sound of a big party already happening right now, and the invitation to it. I graduated from elementary school that June and asked for the LP as a graduation present; I played it repeatedly, the way I would repeat every new Beatles album, and wonder about this Dylan guy pictured on the back cover with the group, the guy who had written “Mr Tambourine Man” and three of the other songs on the album — my friends at school and I were aware of him, but hadn’t yet heard him. This LP is, among many other things, an ideal introduction to Dylan’s writing.

Steve Kalinich: I was living at the YMCA in Hollywood in 1964. At the time I had been doing poetry readings with Esquerita. It was before I signed with the Beach Boys’ Brother Records as a staff writer around 1967.

I went out with someone to an after-hours club. There was a guy with a 12-string guitar, a very good player. We started singing Beatles songs together at the party and a man came up to us and said. “You guys sound great. I have club in downtown Los Angeles called Mrs G’s.” I think that was the place. Over the next few days we all exchanged numbers. He offered us an evening there to just sing Beatles songs.

We had no rehearsals. Jim McGuinn picked me up one early evening in his car. As I remember it was a TR3 or TR4 convertible. I did not have a car. I was living at the YMCA then on Hudson in Hollywood for $15 a week. Harry Hall was the director. So Jim and I played this club. They were not overly receptive but seemed to like us the promoters were very encouraging and receptive.

Jim played a song of his “It Won’t Be Wrong” co-written with Gene Clark, and Harvey Gerst who designed the sound at the Ash Grove. It was electric. The air sizzled. Jim was in the Beefeaters before the Byrds, who recorded it as well. This was 56 years ago.

We did the gig and he gave me his number. He was the first person to take me to the Troubadour before I met Doug Weston the owner. He played in the front room and people would bring their guitars. He was so good. There were no Byrds and I did not yet know Brian Wilson or the Beach Boys yet. Jim introduced me to many people he took me to a few other places. He was just a young guy hoping to play music. Jim was very kind and nice to me. I wonder if he would remember.

A year or so later I played Mrs G’s on Open Mic Night. I was last to go on and the owner came up to me and loved the spoken word. Bob Lind, who later did “Elusive Butterfly,” was there and very supportive. It was an amazing time. I was performing “Candy Face Lane” in the sixties a dark take on the war and the world. I was already into the peace movement.

From that same YMCA I met the guy Jim Critchfield who worked with Jay Ward Productions of Bullwinke fame that led to my signing with Brother Records my first break. I met Al Jardine at that YMCA when I signed with Brother Records while I was still living there.

The day I got my advance check I moved to Brentwood, California, and I eventually bought a house and condo. It was the beginning. I am forever grateful.

I did not see Jim again. He later changed his name to Roger after being involved in the Subud spiritual movement around 1966.

Roger McGuinn: I had been flirting with a name change from the Village. I got interested it in New York and sorta followed through in LA. By 1967 I was into it whole hog. Legally, I only changed my middle name. My first name is still James. If someone wrote a check to Jim McGuinn I could still cash it. (laughs). I switched my middle name. It was Joseph and I switched it to Roger and started using Roger as a first name.

There was a Subud house in downtown LA on Hope Street and the Beach Boys used to hang out there. I remember that. Then, Brian (Wilson) formed his own chapter at his house during his ‘sandbox’ phase.

I saw weed in the Village. Alcohol was definitely a square thing to do. Only the tourists drank alcohol. Like, you’d be at the Gaslight, and you would hear, “This tourist came in and asked for a martini.” And, everyone would laugh. “Are you kidding?”

I tried my first acid in 1961 in San Francisco when it was totally legal. It was from the Sandoz labs. It was great. I loved it. I noticed all the colors that were intense and everything was kinda dreamy. We were living in a commune in the Mission District. A bunch of us were living in a house. It was a wild scene. It was fun. Crosby and I later took acid in Los Angeles and we’d walk around. I remember going to Will Wright’s Ice Cream Parlour on Santa Monica Boulevard.

Ray Gerhard was the engineer at Columbia Records when the Byrds started recording. And at the time Columbia was a middle of the road record label, and they were scared of rock ‘n’ roll. So, Ray, to protect his precious equipment would put limiters on everything, compression, and double compress it for the Rickenbacker, and that is what gave it the wonderful sound. When I heard the sound for the first time I could not believe we had done it. It knocked me out.

At the time I was on the band track with the Wrecking Crew guys, and that was fun, and we did the vocals, and it was all different parts. But when it all came together on the playback it was bigger than the sum of its parts. I couldn’t believe we had done it. It sounded so creamy, rich, big and full. Well I did engineer my vocal, but it wasn’t to match the Rickenbacker but to get between John Lennon and Bob Dylan’s vocal. I wanted to try and hit that niche there between the two of them.

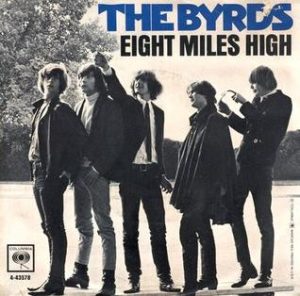

With the Byrds we over dubbed with the Rickenbacker, like the lead break on “Eight Miles High” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” They were not done with the band track, we just did a rhythm track and I would go in and do the leads until I got it right.

Chris Hillman is a very gifted musician. The way he transitioned from mandolin to bass was amazing in a very short. I don’t know if he was completely influenced by (Paul) McCartney but he had this melodic thing, I guess more from being a lead player. He incorporated a lot of leads into his bass playing.

David Crosby an incredible singer for harmonies and he’s written some wonderful songs as well. A good songwriter. I also really appreciated his rhythm guitar work. I thought he had a great command of the rhythm part of it and also finding interesting chords and progressions.

The Byrds’ vocal blend? We sang together well. I give the credit to Crosby. He was brilliant at devising these harmony parts that were not strict third, fourth or fifth improvisational combination of the three. That’s what makes the Byrds’ harmonies. Most people think its three-part harmony, and its two-part harmony. Very seldom was there a third part on our harmonies.

Jim Dickson was definitely a large part of the formation of the group and the attitude. It was Dickson’s pick to do “Mr Tambourine Man.” He got a demo of it before (Bob) Dylan released it. Jim loved the song. We didn’t get it. He had to bring Bob Dylan around to the World Pacific Studio for us to do the song at all. Dylan came over with Bobby Neuwirth and we played “Mr Tambourine Man” and “All I Really Want to Do” for Dylan and Bobby, and Neuwirth said, “Wow. You can dance to it.” After “All I Really Want to Do,” Dylan said, “What was that?” And we said, “That was one of your songs, man.” “I didn’t recognize it.”

After “Mr Tambourine Man” we just loved Bob Dylan’s writing. I had a real heart for his lyrics and really sang them from the heart.

I love “All I Really Want to Do.” It’s kind of a simple little love song, you know, but it’s got a really sarcastic whimsical attitude. He doesn’t want to be hassled. He just wants to be friends. We changed the arrangement from the 3/4 time to a 4/4 time.

We became his ‘unofficial, official’ band for his stuff. I remember when Sonny & Cher got the hit with “All I Really Want to Do,” Dylan went, “Oh man, you let me down…” Normally, a writer would be happy to get a hit with his own songs. Who cares who did it? He was on our side.

We did “Chimes of Freedom.” I loved the imagery. You can’t pin it down as a peace song, or whatever, but it’s got overtones of that. It’s brilliant. I just identified with it and could relate to it.

I remember one time Bob took me aside, I went over to the hotel he was staying at and said, “You know, I used to think of you as just an imitator but I heard ‘Lay Down Your Weary Tune’ and listened to that and you’re doing something that wasn’t there before. That’s really good.”

Dylan’s stuff is brilliant. I coined the term that he was the ‘Shakespeare Of Our Time.’ It was like knowing Shakespeare here. Dylan was carrying on Kerouac and Ginsberg. The baton had been passed. I remember Ginsberg said “I think we’re in good hands.”

The Byrds’ first concert. February 4, 1965. (Courtesy of Gene Aguilera)

Gene Aguilera: On February 4, 1965, by divine intervention, this 11-year old was invited to a concert by his Uncle Ernie. Turned out to be the Byrds at East Los Angeles College. I had no idea who they were. Mr Tambourine Man wouldn’t be released for another six weeks. And I find out many years later, this was the Byrds first paid gig booked by no other than Lenny Bruce’s mom, Sally Marr. Needless to say, the Byrds blew my mind so much that I got their autographs on the school program, which I proudly still have to this day.

They had the look of cool. Part Sunset Strip hippie along with English Invasion swagger. And the bass player? Quiet, mysterious, and talented. Chris Hillman was his name. Did the Byrds give birth to the country-rock genre here in Southern California? Very possible . . . if not, they were pretty damn close.

Just three months later, I began to hear hourly commercials on KRLA that the Rolling Stones were coming to town. I begged my dad Larry to take me to see them at the Long Beach Arena as part of an early birthday gift. Luckily, it worked out. And who was the opening act? The Byrds.

I’ve always loved the Byrds, through thick and thin, and all their changes. I bought them all, including every solo album. The Bible-sized tome The Byrds Timeless Flight Revisited by Johnny Rogan has a place in my book library.

I followed Chris through his stints with the Flying Burrito Brothers, Manassas, and the Desert Rose Band, where at last he assumed the position of a front-and-center man. A must watch on YouTube is their version of “Why You Been Gone So Long,” and seeing Hillman decked out in his blue Nudie jacket looking so confident, animated, and even smiling.

In the late 90s, my good friend Allen Larman invited me to a Hillman live radio performance on his parents show FolkScene (KPFK-FM). Allen knew how much of a Byrds/Hillman fan I was and we all got to hang for a couple of hours. A few years ago, I even planned a California-by-car family vacation around a Chris Hillman/Herb Petersen gig at the Clark Center for the Performing Arts in Arroyo Grande. And to take things full circle, how could I miss the Byrds Sweetheart of the Rodeo 50th anniversary concert in 2018 at the Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles while surrounded by all my music-loving amigos?

Guy Webster: The Byrds came to me from Terry Melcher, who was producing them for Columbia Records. In December 1965 I attended the Bob Dylan press conference held in the Columbia Records Press Room that was arranged by Billy James from the label. You don’t work with Bob. There’s not that connection there. You just do your thing.

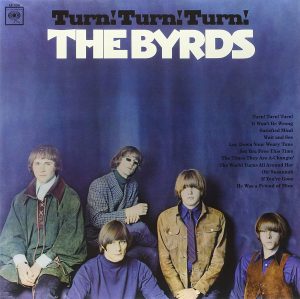

I went to the recording sessions for the Turn! Turn! Turn! album over on Sunset and Gower. I didn’t think of them as folk singers, more like rock crossovers. I loved their artistry and sound of the guitars. They came over and I did the session on my big 4 x 5 Sinar camera. I had them sitting on the ground before this backdrop I’d made. I was getting hip to what would happen to my cover photos; you’d leave space for graphics. I didn’t want my picture to be crunched so I gave them a full bleed with space for the words “Turn! Turn! Turn!” up on top. So I let the blues just sort of drag down to them. It was like they were almost on strings if you look at the photo carefully. I was thrilled with it. And it got nominated for a Grammy.

I also did some photos of them for publicity and they were dressed for an Edwardian portrait. I like to think the Beatles copied it, just look at some of their photos around the time of “Strawberry Fields.”

David Crosby was brilliant but difficult. He’s an Ojai kid. His father was in films. He had a chip on his shoulder. Michael Clarke was so sweet and nice. Chris Hillman – pure musician. We stayed friends. I loved Roger McGuinn’s guitar work and Gene Clark’s voice.

Denny Bruce: It was powerful hearing “Mr Tambourine Man” coming out of every open car window, not just on the Sunset Strip, but where ever people were letting their inner freak-flag fly. I liked seeing a guy or girl driving with a tambourine around their neck, which they would bang on when the song came on the air. In 1965 I still lived in the San Fernando Valley, without a car, but I had my Valley girls picking me up every night, wearing their homemade bell bottoms, on a Cher level. They felt safer with a dude in the car.

Henry Diltz: I knew the Byrds as fellow musicians when I was working with my own group, the MFQ. To stand there and watch McGuinn play that Rickenbacker 12-string was mesmerizing. It just put me into a place, and the harmonies, those were the songs we heard everyday driving down Sunset Strip on the radio. So, to me it was magic. I didn’t see the Byrds play a lot in 1965 and 1966, except once in 1966 in downtown LA.

Roger McGuinn: In 1965 the Byrds went to England to do an initial tour of the country. There were brilliant moments on the first trip over to England in 1965. We met the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. We had met the Stones before, but we got to hang out together in England. We met a lot of people and hung out at a lot of parties. Paul McCartney gave me a ride in his Aston Martin at a night at a club, The Scotch of St James.

It was amazing. George Harrison and I went over our first guitar licks and talked about them and compared notes. Stuff like that. It was incredible. The audiences then in 1965 were basically little girls. And they were screaming and liking it. But the press ate us up because we were billed as “America’s Answer to the Beatles.” And it was like a football game to them. It was a competitive thing and where they couldn’t let us get away with that, which is understandable. And the fact was that we were a green band. Michael Clarke was very inexperienced as a drummer.

I remember at the Blaises club Chris Hillman was so nervous that he broke a bass string, which is really hard to do. (laughs). He did! We weren’t firing on all cylinders there. It wasn’t musically that great. And we got some awful reviews. Then, I got the flu, and Michael wanted to quit. It was kind of a nightmare.

On the good side we hung out with the Beatles and the Stones then. In 1967 when we came back again we did a fan club event at the Chalk Farm Roundhouse that I remember. That was fun. At the end of the tour, the Byrds played a surprise gig at Blaises which Paul McCartney attended.

My favorite recording in 1967 was John Coltrane’s Africa Brass. We were on the road, and I had bought a Phillips Cassette Recorder in London, and it was such a new invention at the time there were no pre-recorded cassettes on the market. But, I had a couple of blanks that I picked up. And we stopped somewhere in the mid-west, Crosby knew somebody there, so we went over to this guy’s house, and he had the latest Ravi Shankar and Africa Brass. And, so, I guess this is music piracy, but I dubbed Africa Brass on one side of the cassette and Ravi Shankar on the other. And we strapped the cassette player to a Fender amp on the bus and we just kept turning the cassette over and over and listened to that thing for a month on the road. We loved that music, which influenced “Eight Miles High” later.

The break on “Eight Miles High” was a deliberate attempt to emulate Coltrane, like sort of a tribute to him, if you will. We had heard Ravi Shankar earlier. I had a physical response to that Coltrane album the first time I heard it. It felt like a white hot poker was searing through my chest. It cut deep into me and it was a little painful. But I loved it. It just opened up some areas in my heart and head that I hadn’t known about.

I think what I loved about Africa Brass was the improvisation of course, but his attitude comes through, a forceful, rebellious attitude. Like rock ’n’ roll. It really knocked me out.

Dr James Cushing: “Eight Miles High” from the Byrds’ third album, Fifth Dimension (1966), represents one of rock music’s landmarks, high points, supreme accomplishments, strongest evidence that this mass-produced musical format is capable of achieving the status of modern art: this single song offers what Wallace Stevens called “a new understanding of reality.” It stands along with “Satisfaction,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Good Vibrations,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Purple Haze,” “Anarchy in the UK,” and no more than two or three others. Every way that a record can be great, this is.

I have a theory that many young people were introduced to jazz improvisation in the late 60s on a ‘stealth’ basis — that is, the idea that, if jazz were to played on loud guitars and marketed as rock, it would fly. “Flute Thing” by the Blues Project and “Gold and Silver” by Quicksilver Messenger Service were early examples.

Of course, Bill Graham liked to sneak the Charles Lloyd Quartet onto Fillmore triple-bills, and then came Cream — but “Everybody’s Been Burned,” the David Crosby tune that loses outside one of Younger Than Yesterday (1967), is another primo example of stealth-jazz, a tune whose mood has nothing to do with “rock” and which serves as a vehicle for improvisation.

Kirk Silsbee: Younger Than Yesterday is a very important Byrds milestone. To my ears, it’s the first full expression of the band—as writers, players and conceptualizers. True, 5D was the album where they predominantly generated the important material from within the group. On Yesterday, all of those categories are more fully realized, and we’re hearing a matured band that—like a thoroughbred horse—has won some races and now knows what it can do.

Hillman gave us a song that extended the Gene Clark ethos: “Have You Seen Her Face.” It’s a wistful, love-struck song, and a perfect track. They Byrds’ patented harmony is pitch-perfect, McGuinn’s lead guitar line is stinging and memorable, and Hillman’s bass line undergirds the tune in a strong, dependable, almost complex way. But that was the way he played: with a mobile, linear bottom line that never drew attention itself, but whose strength and fidelity to the song were unquestionable.

If there was ever any doubt as to Hillman’s bluegrass roots, there’s “Time Between,” purportedly the first tune he ever wrote. The Byrds had recorded “Mr Spaceman,” a Buck Owens-sounding tune. But “Time Between” was rocked-up bluegrass and, as such, it was a cornerstone of the country rock that was formulating.

Yesterday is where we get to take the full measure of Hillman. His playing on David Crosby’s “Everybody’s Been Burned” is one long, lyrical, melodic, contrapuntal, linear statement. It’s the sturdy spine that the whole record is hung on, and if you were to remove Hillman, the whole tune would fall apart. I can’t think of another rock record of the day that utilized the electric bass in such a creative way.

Roger McGuinn: Our Younger Than Yesterday LP, produced by Gary Usher, was mostly recorded in late 1966, and released in January ‘67. Chris played us “Have You Seen Her Face” in the studio and we cut it. We weren’t into making demos back then. Demos came along in the ‘80s. (laughs).

“So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” as a single came out in January, and in March. “My Back Pages” followed. Things like that. Chris and I knocked that off, “So You Want to Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” in very late 1966 at his house. It really wasn’t about the Monkees. We were looking at a teen magazine, and noticing the big turnover in the rock business, and kinda chuckling about it, you know, a guy was on the cover that we’d never seen before and we knew he was gonna be gone next issue. A funny little song. People didn’t know how to take it. We just meant it as a satire. We got along well and we wrote well. Actually, Crosby and I wrote well too for a while together when we were writing, and so did Gene and I. We had some good times writing songs.

Hugh Masekela had played on our record of “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star,” and I had toured with Miriam Makeba. So I knew who he was. It was always wonderful to play with someone of Hugh’s caliber on the session. The song was a satirical jab at how they make teen idols. That was what it was all about.

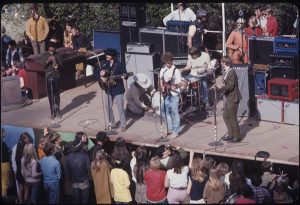

The Byrds with Hugh Masakela. Fantasy Fair & Magic Mountain festival, June 10, 1967. (Photo: Henry Diltz)

Heather Harris: I saw the Byrds along with Buffalo Springfield, the Doors, Peter Paul & Mary and Hugh Masekela at a CAFF (Community Action For Fact and Freedom) benefit concert on February 22, 1967 At the Valley Music Center in Woodland Hills, California. Jim Dickson, Alan Pariser and Ben Shapiro produced the show [Others involved in the event were B Mitchell Reed, Ed Tickner and Derek Taylor] that helped defray the legal expenses of teenagers arrested by The Los Angeles Police Department ‘Riot Squad’ regarding the 10:00 PM curfew incidents on under 18-years olds around the Sunset Boulevard Pandora’s Box club.

Jim Dickson: It wasn’t a riot at all. Of course not. They instigated some of those things. There were a lot of people who weren’t Strip regulars. It became the place to be which was all right. And very few shop owners complained to me.

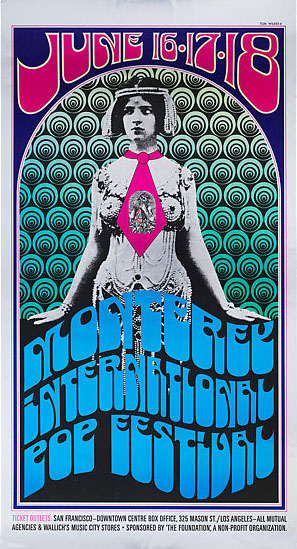

After the CAFF show Hugh Masekela said to Alan, “We gotta do another one.” Alan got it (Monterey International Pop Festival) rolling and took it to Benny Shapiro. [Lou Adler and John Phillips subsequently became involved, bought Shapiro out, and made the event a non-profit three-day venture].

Roger McGuinn: I had a lot of history with a lot of people at Monterey. I was also on the Board of Directors and involved in it. It was a real wonderful thing that they did. Derek Taylor was our publicity guy who worked with the Beatles.

I was at front to see Ravi Shankar. And we were into him before because of his records on World Pacific, which was a very cool label. I met Dick Bock. I knew Benny Shapiro, who was a friend of Dick’s, and Benny was the catalyst to getting us signed to Columbia. And, we turned the Beatles onto Ravi. I saw Jefferson Airplane. We were friends. Paul (Kantner) played Rickenbacker because of the Byrds, and the Beatles. We were Rickenbacker buddies. Crosby was friends with him, too.

This was a different thing entirely. It was almost like it wasn’t about the music business. It was about the music and friendships, joy and camaraderie. It was almost a religious thing.

The sound system was a big departure from what we had. We were using little MacIntosh amps and I don’t know what kind of speakers for our sound as the Byrds. So to have these massive speakers and big amplifiers was a big thing. And, having monitors for the first time.

At the Monterey International Pop Festival Hugh Masekela joined us on trumpet along with Big Black the percussionist. What a thrill.

And you can see our Monterey Pop set on You Tube with David talking about the Kennedy assassination. “Renaissance Fair” our opener that I wrote with David was the perfect song for the festival. We had just recorded it. It was another new song. We were doing new material, and not relaying on our hit records. I like “Lady Friend,” one of his songs.

I didn’t know David was going to sit in with Buffalo Springfield, and that wasn’t really a big deal. What was happening was that we were not happy with each other, like a marriage breaking up. He was really upset because we didn’t do his song “Triad.” That was the big bone. He wanted to be the lead singer of the Byrds, you know, the head Byrd. That wasn’t happening. To his satisfaction we were sharing vocals equally.

At Monterey I was trying to be a trouper, like Bobby Darin taught me, and try and soldier on and do it. “He Was A Friend Of Mine.” I was surprised by David’s Kennedy rant on stage. I mean, first of all, I wasn’t sure I agreed with it. The myth-busters do a fairly extensive analysis of the whole thing and it looks like it could have been one bullet, ya know. So, I don’t know. My feeling was that it was not professional and my only concern. An inappropriate moment.

Before the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival I was driving my Porsche up La Cienega, and got around to Sunset, and Jim Dickson pulled up in his Porsche, and signaled for me to roll my window down. “Hey Jim, you ought to record Dylan’s ‘My Back Pages.’” I said, “OK. Thanks.”

The light changed, I drove back up into Laurel Canyon, and pulled out the Dylan album that had “My Back Pages” and learned it. I then took it to the studio and showed it to the guys. And Crosby hated it because he was mostly upset because he wasn’t getting his own songs on the album, and the reason why he left the band. There was a riff in the band, and he wasn’t getting as many as some of us.

So anyway, I liked “My Back Pages” and don’t remember any resistance from anybody else in the band, just David. And he was just mad because he wasn’t getting his songs. And it was a hit and a good tune. I’m real happy with it. It was Dickson’s suggestion and I hadn’t thought of it as a song for the Byrds repertoire.

I liked the wisdom of the song and it’s a very insightful song on the thing that happens when you think you’re so knowledgeable and wise when you’re real young. And then when you get a little older you realize what you didn’t know.

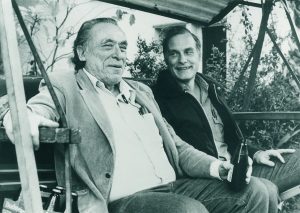

Chris Hillman and Roger McGuinn, 1967. (Photo: Henry Diltz)

Jim Dickson: For the most part, the Monterey International Pop Festival was a positive thing and the only thing that wasn’t positive was David Crosby’s speech. That embarrassed me. You can’t imagine the ego involved. Never was a team player.

Ravi Shankar had performed at Monterey and earlier had played at The Renaissance a number of times. And Dick Bock at World Pacific recorded him. I took David to one of Ravi Shankar’s recording sessions at the World Pacific studio and that was where he really heard that kind of music for the first time.

Right after Monterey, the Byrds fired me. I had been the one who had gotten them into “Mr Tambourine Man,” “Chimes of Freedom,” and all that Dylan stuff.

When I got home from Monterey, in Monday morning’s mail was a letter from the Byrds firing Eddie Tickner and I. [Dickson was the Byrds’ first manager with Eddie Tickner, and introduced the Byrds to their booking agent, Benny Shapiro].

But while I was in Monterey (Roger) McGuinn didn’t mind having me find the words to “Chimes of Freedom” and ran all over Monterey to find them because he could not remember the words and I wanted them to sing the song and he agreed he should do it. So I went and got him the words with him knowing he had already fired me and Eddie and I hadn’t got the letter.

Even though they had fired me, and they didn’t understand I wasn’t bitter about it. I mean, I got further with them than I thought I would.

Johnny Rogan: There were several reasons why Jim Dickson was fired. David Crosby had become entranced by Larry Spector, who was representing Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda, Hugh Masekela and various Monkees. Crosby persuaded the others that a change of manager would be a good idea, something he later regretted.

Dickson could be overbearing and would never play the sycophant. He always told the Byrds what he thought about every aspect of their career, music or personalities – whether they wanted to hear it or not. Beyond the issue of personalities, his leaving was also symptomatic of the times.

In 1967, the Rolling Stones dismissed their great mentor Andrew Loog Oldham and there were strong rumors that the Beatles might not be renewing their contract with Brian Epstein, who died that same summer. It seemed that change was in the air everywhere and artistic autonomy was the new watchword.

David Kessel: I was a big listener of what Chris Hillman was doing on the various albums. I knew he had deep country music roots and brought some of that to the table culminating with Sweetheart of the Rodeo. His bass playing is very musical and has a big round tone. Chris helps lay foundation and cuts through.

Roger McGuinn: On our [1968] Sweetheart of the Rodeo, Chris got the demos of the two Dylan songs “Nothing Was Delivered” and “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” in the mail that we did. Dylan as a songwriter was so much better than everyone. We had been out of touch for a few years and it was interesting to notice that at this same period he was going in the same musical direction we were in.

Before Sweetheart Of The Rodeo began I was planning, or toying with a sprawling double album concept collection of roots, bluegrass, folk, country, experimental, Appalachian, Elizabethan, and space age music.

It was a very ambitious idea, it was actually bigger than Americana, it was world music. It was going to be the origins and the history of music if you will from the beginning: Dawn of man up to the present day, incorporating Elizabethan music and how that came over to the Appalachians and got distilled and became folk music and country music and rock ‘n’ roll and the African blend. It was to cover everything, including jazz, and finally go off into space music and synthesizers and go off the top and just into the future.

But I couldn’t get anybody to go along with me and got outvoted. I really thought that would be fun. ‘Cause I was interested in all those types and all those forms of music. I thought it would be a nice thing to put in one package and have it all there. It would have been interesting, but in retrospect all the albums the Byrds made you’ve kind of got that: Sci-fi, early stuff, “Renaissance Fair,” “CTA-102.”

I really loved Sweetheart of the Rodeo. I wasn’t upset about it. It wasn’t a band meeting and there wasn’t a vote taken it was simply that I couldn’t get anyone else to go along with me on this bigger idea.

Chris Hillman met Gram Parsons in a bank and then Chris invited Gram over to our rehearsal. We were rehearsing and Gram came in, and there was a keyboard of some kind and I asked Gram if he could play any McCoy Tyner because I wanted to continue in the vein of “Eight Miles High” jazz fusion with a (John) Coltrane kind of thing. And he sat down and played a little Floyd Cramer-style piano and I thought this guy’s got talent. We can work with him. That was my original thought.

Not knowing that he had another agenda, and that Chris and he were like kinda in cahoots and going to sway the whole thing into country music. But I really liked country music having come up in folk I always considered country music, especially the Hank Williams and the traditional country music that Gram was into a part of folk music, so it wasn’t alien to me.

I was a fan of country music and we were dabbling in country rock before Gram came in. “Oh Susannah” and “Satisfied Mind,” a Porter Wagoner song. And even “Mr Spaceman” has a country beat to it. I mean, it’s a silly sci-fi song but it’s got a country, Buck Owens approach kind of song. We were dabbling in that and something we did for fun, and the only difference when Gram came along is that we decided to do an entire album of it and do nothing but that. That was the difference. And I think it was because Chris had an ally. That’s what he feels. He found an ally in Gram. And the two of them kind of swung it over to that at the time.

Sweetheart of the Rodeo has taken on a life of its own. It’s far exceeded my expectations for it. At the time we were just having fun and we wanted to do it. In Nashville when we recorded, we had party tools…It’s probably the hottest album the Byrds ever did and it’s ironic to me. It made the difference by doing it in Nashville and the authenticity it would not have had if the whole thing had been done in L.A. [Drummer] Kevin Kelly was easier to work with than Michael Clarke. He was more precise in the recording. He was a nice guy. We liked him.

During Sweetheart there was collaboration and there was unity. We used to play poker every day. I mean we were buddies who would sit around, drink beer and play poker. And when we were off in LA we’d ride motorcycles together. I mean, we were having a good time. It wasn’t like there was this weird animosity. There was very little of that going on. It was a friendly band, maybe too much fun. We enjoyed it.

“Lazy Days” is a cool song Gram wrote. They’re all good songs and we have to give Gram credit for bringing a lot of them to the sessions. Gram brought in a batch of songs. “Hickory Wind,” William Bell’s “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” and the Louvin Brothers’ “The Christian Life.”

We all got along great with the musicians in Nashville and stayed at this Ramada Inn and played poker all day until the sessions at night, and had a ball. We were country boys. We got into it. I mean we had cowboy hats and boots. I loved it. A very enjoyable experience. We were just role- playing, even Gram. He wasn’t that kind of kid. He was a folkie. He was a preppie.

Basically Gram got turned on to Elvis (Presley) when he was 10 years old, and that changed his life and he wanted to be a rock star, which he eventually became. And then he got into country, he got into Buck Owens and he got into Waylon and Willie. And I started harmonizing with Gram, and he and I had a good blend. I was getting into it. It was fun. He and I had a lot of fun for a long time up until he left.

Producer Gary Usher was amazing when he was doing this. He was a ‘tech head’ for the time and very innovative. We had done this phase-shifting he had done with two tape machines. And he took that idea, which was moving the machines closer together, after recording them spread out, and then one would phase shift, and move them and make a 16 track out of two eight-tracks. I was loving it. He was great. Gary and I were kindred spirits and very creative.

The Byrds released a single of the Goffin/King composition, “Goin’ Back.” Gary Usher got the tune and brought it to us in the studio and played it for us as a demo. I didn’t know of Carole King, even though I had worked in the Brill Building earlier on. And, I had never heard of the Goffin/King songwriting team. But I loved the tune and thought it was really good. Gary explained that these were Tin Pan Alley writers who had just kind of taken a sabbatical and come back and revamped their style to be more contemporary, like we were doing. So it really fit well I thought. We learned it and put a kind of dreamy quality into it.

After Sweetheart, Chris left, Clarence (White) came along, finally we got (bassist) John York, Skip Battin, Gene Parsons and it was a country rock band. That was the last incarnation of the Byrds.

I think what Gram really wanted to do was get rid of me and get a steel guitar player. [Sneaky Pete Kleinow]. Yea. (laughs). Let’s form the Burrito Brothers and call it the Byrds basically. I didn’t want that to happen. I had put too much into the Byrds.

Chris Darrow: I got to know Gram Parsons a little bit. He and Bernie Leadon would come out to my house and visit. The Burritos even did a concert right across the street from my house; I designed the poster for the gig. Gram had a mentor from the east coast who was teaching in Claremont at Pomona College. His name was Jett Thomas.

I think that country rock was a West Coast phenomenon and that the bands were the originators, not the individuals. The East Coast solo artist was a different breed from the West Coast collaborative unit. Most of the situations that arose in the West Coast were band situations and whether there was strife or not, the element of the band usually prevailed. Guys like Gram Parsons were much more self-directed and solo oriented than most of the West Coast personalities that worked with him. Chris Hillman has always been a good team player. Bluegrass training!

The use of studio musicians to create certain styles sometimes goes against this credo. Bringing in a steel guitar player is what the Buffalo Springfield did on “Kind Woman.” The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo wasn’t played entirely by the members of the band; Earl Ball and JD Maness were brought in.

What I’m saying is that country rock did not sprout out of the head of Gram Parsons and everybody else followed. It was a process and he was a solo artist. His independent income allowed for him to be free of the constraints of playing with ‘the guys’ for bread. He was a talented guy but I am one who refuses to put a single name to the father of this genre.

The fomenting of this music started early in all our heads and each opportunity to express it was taken. A steel guitar is not the only criteria for country rock music. Clarence White invented a device to play the electric guitar like a steel guitar. He and Gene Parsons developed a B string bender to bend the second string in the same manner as a steel guitar. It is a hard style to play and only a handful of musicians have mastered this technique. I had a chance to play in his band at the Ash Grove a month before his untimely death.

The Flying Burrito Brothers, Palm Springs Pop Festival. April 1, 1969. (Photo: Heather Harris)

Heather Harris: The Flying Burrito Brothers were much touted by my friends who worked at A&M Records (their label) who regaled me with stories of how their promotional efforts on their behalf backfired, like stuffing real straw hay into their publicity mailers, all of which were seized before delivery by the US Post Office who suspected far more illegal botany going on.

Since I was still too young to get into clubs, the first opportunity to photograph the Burritos was at the April 1, 1969 Palm Springs Pop Festival, open to all ages. And I was packing a better camera. However…this was the first time show I’d attended that had blocked off the entire front of the stage from the audience or photographers like me. I was as determined then as I am now to get great live shots, so I just tore down the offending chicken wire, entered the rarefied area and took a photograph of the Flying Burrito Brothers, Gram Parsons, Chris Hillman, Chris Ethridge and Sneaky Pete Kleinow, all accoutered in their infamous custom Nudie suits–Gram with cannabis leaves and pills, Sneaky with pterodactyls etc.).

I only got this one shot of the Burritos because suddenly eight thousand people rushed forward to join me in the once-blocked off area, and I was jostled terminally away from any further photography. But apparently those pushing stagewards continued in their spirit of surging and mobbing, eventually rioting throughout toney Palm Springs all the way to Taquitz Falls Park.

It was one of the first instances in utter failure of concert crowd control for festivals ending in rioting, quite some months before the Rolling Stones’ Altamont downer and I, dear reader, may be responsible for its inception. I’m pretty sure the statute of limitations has run out, hence my confession…

Daniel Weizmann: It’s a common thing to point out that the Byrds married Dylan to the Beatles and created the sixties—but I think it’s equally important that the marriage took place in Los Angeles. For all their genius, neither Dylan nor the Beatles ever bring the kind of bright, spacious, sunlit sense of air and ocean that is part and parcel of every Byrds record. Even a simple blues like “I Know My Rider” soars like a runaway kite caught on sea breeze in their hands. Make no mistake: the Byrds are a surf group.

It’s no accident that the Paisley Underground flowered here. For us LA kids who were born in the late ’60s, you can’t imagine the civic pride we felt stumbling on a Byrds Greatest Hits record in the library on Hillhurst, seeing those photos of them lounging among the daisies that could have been Bronson Canyon or Fern Dell or some other sun-splashed LA grove. The myth of the sixties belongs to everyone, but the Byrds were ours.

I had just turned 15 when I checked that LP out of the public library. It was the early ’80s and I was becoming ever-so-slightly bored with punk. What happened next was either crazy coincidence or magnificent fate. Two nights later at a “normal” Marshall High party–ya know, Michael Jackson on the hi-fi, cute girls in pastel, vodka in the punch–some chick I’d never seen before led me to a dark corner of the house and asked me if I ever tried magical mushrooms. I had no idea what they were, but, improbable as it sounds, maybe she was hitting on me! I ate ’em.

I don’t remember the party. I don’t even know who gave me a ride home. But as long as I live, I will never forget being back in my room, slipping on the big Panasonic headphones, and putting the needle on Side One.

Souther Hillman Furay, 1974.

Bill Mumy: In 1968, I bought a sunburst Fender Precision Bass for $242.00 from Splevin’s Music store on Pico Blvd in West Los Angeles. I still have it and have used it for over half a century now. I chose that particular model because it was the one Chris Hillman was using with the Byrds at the time.

I saw the Byrds play live at the 1968 Newport Pop Festival. The members of the Byrds for that gig were Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman, Clarence White and Kevin Kelley. I had been a big Byrds fan since their first album was released in 1965. Marta Kristen, who played Judy Robinson on Lost in Space knew I was a folk music kinda guy and she turned me on to the Byrds and I took to them in a big way.

Chris Hillman was a bluegrass mandolin player who accepted the invitation to become the Byrds bass player before the band even had settled on a name. His approach to the bass was always fresh, fluid and melodic. Within a very short amount of time, he became a truly brilliant bass player.

Listen to his bass lines in “Eight Miles High,” “Renaissance Fair,” “So You Want To Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star,” “Everybody’s Been Burned” and “My Back Pages.” They are BOSS. Chris stepped up and delivered a big batch of outstanding original songs for the Byrds when they needed him to and his lead vocals shined.

Chris Hillman has always excelled at the tasks he’s accepted.

I’ve followed his career since the beginning. He’s a wonderful singer, songwriter and musician: A rootsy, soulful artist. I liked the first Burrito Brothers album, but I didn’t love it. I liked the second one with Rick Roberts more. Sonically, that first Burritos album didn’t win my ears over.

When Chris teamed up with Stephen Stills to form Manassas, I got into that band as well and Chris’ “Bound to Fall” is a highlight from that group. Manassas always kind of reeked of excess to my ears though. They were certainly no CSN& Y.

I was absolutely excited when the original five Byrds reunited and anxiously awaited the release of that album that turned out to be a pretty major disappointment. Gene Clark certainly delivered the goods and Chris did too. But… it was far from great.

I had lost my youthful cheerleader attitude when the Souther Hillman Furay band was put together. It obviously was a ‘corporate’ move and although I bought those albums as soon as they were released, they too disappointed. Once again, my hope was fired up when McGuinn, Clark and Hillman formed. Three Byrds? Should be great! Wasn’t. But Chris was always steady. He sang well. He played well. The songs just weren’t there and to me, there was a feeling of trying too hard.

Until… The Desert Rose Band. THAT group was a grand slam home run. Chris was finally the indisputable front man. It was HIS band. That group played and sang fantastically. Finally, original Byrd, Chris Hillman, found great commercial success without being someone else’s wing man.

One of the very best gigs I ever attended was McGuinn, Hillman & David Crosby uniting to reclaim the name the Byrds back in 1989. Chris brought in his Desert Rose band mates John Jorgenson on guitar and Steve Duncan on drums. What a show! How I wish that band had stayed together. But, fate had other plans. Their attempt to get the Byrds title back was unsuccessful and that was the end of that.

On July 24th, 2018, I attended the Sweetheart of the Rodeo Anniversary gig at the Ace Theater with Chris and McGuinn backed by Marty Stuart and the Fabulous Superlatives. It was indeed a fabulous night of classic Byrds music. Marty Stuart truly honored the late great Clarence White throughout the night playing amazing riffs on Clarence’s ‘B-Bender’ Telecaster.

I also enjoyed Chris’ most recent album, Biden My Time, although because it sadly turned out to be the final project from Tom Petty, there’s a cloud of sorrow attached to it.

I’m looking forward to reading Chris Hillman’s book. He’s never let me down.

***

Chris Hillman is a walking tradition. And, if you ask him a question he’ll always tell you exactly what he’s thinking. Below are excerpts from dialogues I conducted with Hillman in 2007, 2010 and 2014.

Q: Talk to me about the very late fifties and early sixties music world.

A: But there was also that period from 1959 to the Beatles in late 1963 that was a dead period. That was when folk music was just jumpin’ on its hind legs there. And so who comes out of folk music? The Byrds, John Sebastian, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Stephen Stills, Richie Furay, the Mamas & the Papas. Four bands that were really successful with hits on the radio came out of folk music. And, of course, we were all emulating the Beatles to some degree at first. The Byrds certainly were. And then, I mean, my God, when I joined the Byrds they were still doing Beatlesque songs that Gene [Clark] was writing.

But then we got into doing other material. But interestingly enough, out of that folk era, and I’m the guy coming out of the real traditional bluegrass, the other guys are coming out of the New Christy Minstrels. But those four bands took it and incorporated it and were successful but took it and incorporated it. And I think a lot had to do with the folk music emphasis on lyric, on a story, on that whole thing. And, the Beatles, when they became aware of Dylan and to some degree, listened to us a little bit, but they started to write deeper songs.

Before I was even in the Byrds, the first record I ever did was with the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and we did the entire album in four hours. It was a good band. We went out to Griffith Park in Hollywood. Here we are lined up in a color photo shoot appropriate for our age. It still sells and is print from Ace Records.

When the Byrds came along we did one of our very first publicity black and white shots and we’re in suits. I remember us doing that photo in the daytime and it might have been at Shelley’s Manne-Hole club in Hollywood. And there was an older guy who was at that session doing photos. It was so early it might not have been an (official) Columbia publicity photo.

Q: The Columbia recording studio. I loved that place, knowing the history going back to radio broadcasts with Fred Allen and Jack Benny.

A: I remember that Columbia was a union room. The engineers had shirts and ties on. Mandatory breaks every three hours. [Record] producer Terry (Melcher) was a good guy. I didn’t really get to know him. I was shy. Columbia was comfortable to record in there. Terry was good. I liked him. I will say this, and on the Byrds albums I was not mixed back. Sometimes it worked. And I do have to say all five of us were learning how to play. Once again, coming out of the folk thing and plugging in. And we were all learning. Roger was the most seasoned musician, and we all sort of worked off of Roger. He had impeccable great sense of time. His style and that minimalist thing of playing that was so good. He played the melody.

Our first album cover was shot by photographer Barry Feinstein, who was an old friend of Jim Dickson who was our manager.

I know the time period when the only delivery method was an album with LP cover art. The album cover meant a lot then. Jim Marshall was in San Francisco as was Guy Webster in Southern California shooting, and then (Henry) Diltz came along just a bit after and was the next generation. Guy was very good at his job. And, of course, my time with him then I was so shy. I barely said four words within an hour in the early days of the Byrds. He did a great job.

One thing I’ve said before, melody and lyrics, and what our manager Jim Dickson drilled into our heads, the greatest advice we ever got, and he said, ‘Go for substance in the songs and go for depth. You want to make records you can listen to in forty years that you will be proud to listen to.’ He was right.

Here we were initially rejecting “Mr Tambourine Man.” Mind you, I was the bass player and not a pivotal member. I was the kid who played the bass and a member of the band. Initially all five of us didn’t like what we heard on the Bob Dylan demo with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot. We were lucky. And Bob had written it like a country song. And Dickson said, “Listen to the lyrics.” And then it finally got through to us and credit to McGuinn, mainly Jim (later Roger) arranged into a danceable beat.

The Byrds do Dylan. It was a natural fit after “Mr Tambourine Man” was successful. Roger (then Jim) almost found his voice through Bob Dylan in a way. Literally a voice through Bob Dylan in a sense. And then we start doing some Dylan stuff. “Chimes of Freedom.” Great song. “All I Really Want To Do.”

“Bells of Rhymney” is my all-time favorite Byrds’ song. What song best describes the Byrds? I would say that, because of the vocals on it and the harmony. Because of the way we approached the song and we had turned into a band. We had turned into a band with our own style. We went from doing Bob Dylan material and then we take ‘Bells Of Rhymney’ and it’s our own signature rendition of it. It’s not like Pete Seeger’s at all. It’s our own thing. And Michael Clarke, who was a lazy drummer but when he was on he was great. And he’s playing these cymbals. A great experience. I just love that cut.

We did the Byrds’ Turn! Turn! Turn! cover at Guy’s studio at his parents’ house in Beverly Hills. Terry Melcher at Columbia knew Guy, and they had done some work previously. That’s where I first really met Guy Webster.

There we are. (David) Crosby is in his cape. McGuinn has got the glasses on, and the ever so fashionable hounds tooth sport coat. And then Gene (Clark) and Michael (Clarke) and I have our perfectly coiffed Beatle hair. It’s all in blue. Guy’s father was a very famous songwriter. I knew that.

That LP cover and the music on Turn! Turn! Turn! was the breakthrough. The breakthrough record was ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ but the breakthrough album was that. “Turn! Turn! Turn!” is the most recognizable Byrds’ song way over “Mr Tambourine Man,” with all due respect. That’s the Byrds’ song people always remember. It was the LP cover I autographed the most. I only just found out when I attended Guy’s show at the Ventura Museum it was Grammy-nominated for album cover.

Palos Verdes High School, 1966 (Courtesy of Toulouse Engelhardt)

Q: You told me your favorite record in 1965 was the Rolling Stones’ “Get Off My Cloud.”

A: You know why I like it? Brian Jones is on it. The unknown factor of what made the Stones great was Brian Jones and nobody gives him credit. Yes, he was the pretty boy, however, as a musician, he was an unbelievably good musician. There is something about “Get Off My Cloud” where they went from doing a Bobby Womack song “It’s All Over Now,” straight R&B, to within six months to a year they are doing “Get Off My Cloud.”

The record was recorded at RCA studios in Hollywood produced by Andrew Loog Oldham and engineered by Dave Hassinger, who engineered the Byrds when we cut a version of “Eight Miles High” there. Hassinger did “Eight Miles High” and got a little more of an edgy feel. The fact that this was the first time the Byrds had stepped away from the Columbia (Records) embryonic building. It’s very hard to tell the difference of the “Eight Miles High” versions, but the one we did at RCA had a little bit more edge because we felt a little freer, and we hit a homer with it.

Then Columbia said, “We will not accept this because it was not recorded at our studio.” And in those days that was the law. Recording in Hollywood then, and at our age at the time, and not being aware personally, I didn’t think about the environment being an influence. A studio was good anywhere and I didn’t care about the technical part if it was a comfortable place to work, and the engineer was quick and got sounds that were good. But it was in Hollywood at RCA where the Stones did their albums 1964-1966.

So when you came to record in those days, you didn’t go to Santa Monica or the San Fernando Valley, you went to Hollywood. That’s where the studios were. In those days it was RCA, Gold Star, and Wally Heider. All those rooms made all these great records. Remember it was all analog. No digital. And Andrew Loog Oldham cut the Stones on 4-track.

On “Get Off My Cloud” I love Charlie Watts’ drumming and Bill Wyman’s bass playing. That rhythm section…They understated it, less is more. They played it right for that song. Watts and Wyman wasn’t exactly the Motown rhythm section but what they did made it work. Each part of the Rolling Stones was a part of the equation and all five of them made that sound. Mick’s delivery on the “Get Off My Cloud” vocal. He’s involved in that delivery 110 per cent. Once again, Mick is not Marvin Gaye, but Mick gets it when he does it. He puts his entire heart and soul into delivering that vocal. And that’s what counts. At the time Mick did that lead vocal on it he sold it. He sold me that song and he sold me that emotion. His emotion came through as it always does. They have an amazing body of work.

I remember when the Byrds opened some shows for the Stones in 1965 and at a concert in San Diego when they were late arriving. We actually were doing a couple of their songs when they walked in the door because we had run out of material. So we were doing our ‘club set,’ that included a couple of their tunes. We had four or five shows with them. I watched them from the wings. They were good. They were great.

To me, I’m a kid coming out of bluegrass, where you didn’t move on stage and had a glum look on your face ‘cause you had to keep concentrating and playing at breakneck speed on a musical thing. Chris Darrow can attest to the ‘bluegrass showmanship,’ which is nothing there. And, I’m watching these guys, at least Mick and Keith (Richards), just going for it. And my mouth was open. “Wow!” I go back to Brian Jones, who was a real integral part of the band, but he didn’t do much on stage either, he looked great.

Q: You really blossomed on Younger Than Yesterday.

A: I started really writing songs after Crosby and I were on a Hugh Masekela session that Hugh was doing with these South African musicians way ahead of Paul Simon and one of them was a piano player named Cecil Bernard was very inspirational And a gal, Letta Umbulu. A wonderful singer. All the musicians were South African with the exception of Big Black. I played bass on a demo session. And David was a good rhythm guitarist.

I went home and wrote “Time Between” and “Have You Seen Her Face” influenced by a blind date Crosby had set me up with along with other young ladies. There was something that connected with me and that was where I came out of my shell with that session. I came home and wrote songs that entire week after that session. And Hugh we were working with Letta Mabulu, so some of that carried over to Monterey.

Q: The Byrds and Hugh Masekela played together at Monterey.

A: Hugh Masekela at Monterey was one of the highlights, and earlier recording with him was one of the highlights of my life. At Monterey we did Dylan’s “Chimes of Freedom.” I didn’t realize how beautiful that lyric was until years later. And Jim Dickson, and you gotta give ol’ Jim credit, he instilled in us the concept of depth and substance.

He said, “Do you think you’re gonna be able to listen to this 20 years later?” And, here we are yelping about “Mr Tambourine Man” when he brought it to us. “Chimes of Freedom” and the reading, the version we did on that first album was the band. We all knew it. And “Chimes Of Freedom” is a killer. It’s just one of Dylan’s beautiful songs. And he was just peaking then.

At Monterey we played “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star.” It wasn’t personal against the Monkees, it was against the process how contrived it was as a takeoff on A Hard Day’s Night. Nothing against those guys. Michael Nesmith was a damn good musician. Good writer and good singer. And the rest of those guys could handle their chores. Davy Jones was a song and dance guy.

The idea and base line of the song came from playing with Hugh, and when I called Roger, ‘I got a song.’ And he put the bridge there. And the bridge was really from a Miriam Makeba song and he had history with her. Gene Clark has left, David was going nuts and Roger and I were sorta bonding together as I came out of my shell and learning how to write and sing. We got some good things out of it.

At Monterey we did a repertoire that was currently involved in what we were recording and other songs. Gene Clark had just left and had so many good songs that lent themselves to the Byrds’ concept sound that when he was gone we continued to do those songs.

My theory is like the Rolling Stones, when Bill Wyman left that band they never sounded the same to me. We recovered and did a lot of great things after Gene left, but he was a very integral part of the original five people. Roger was a great collaborator. He could write songs with myself, Gene, and David. “Old John Robertson” was a silent movie film director.

I was coherent, and relations with David were so strained at that time it was getting to the cusp, the end of the deal. Here was this beautiful weekend, this diverse lineup. Otis Redding to Ravi Shankar, our set was a disaster. Crosby, you know, I mean you could almost see in the (film) footage where Roger and I were walking away from him. He was ranting about the (John) Kennedy assassination.

He was so unconnected to Roger, Michael and I musically in that particular performance because whatever he was going on, no groove, despite the ranting, inappropriate, as it is now on stage when our peers get up there and start politicalizing, or whatever they’re doing, shut up and sing. Do your music. Don’t do that stuff.

When I finally saw the footage a few years ago and saw our performance, and we’re doing “Hey Joe” a hundred thousand miles an hour and David obviously ingested a few things in the LSD area. Crosby says it in the concert film, the sound system at Monterey. You better believe it. When we started there weren’t even monitors. The guys would have a couple of house system speakers, which were minimum, and microphones.

But really, really upset me down was the performance. I mean, oh my God. That is so bad. End of story. I was up there and I was part of it. End of story. And, you know what? I don’t look back in hindsight anymore but sometimes the one thing I wished I had been I was such a shy little kid back then. I wish I had been as assertive and a little more confident. I would have probably strengthened Crosby out a little more ‘cause nobody did. We didn’t have a captain of the ship, in all due respect to Roger McGuinn. Roger was the Byrds, and he was the Byrds, and he has every right now to go out now and do that entire catalog on stage. Because he was the Byrds.

However, and Roger’s great quote was “We were a band of cutthroat pirates stabbing each other in the back.” We’ll the reason we were a band of cutthroat pirates was that we didn’t have a captain. McGuinn was strong enough to be the captain of the ship. You don’t go into a platoon in combat without an officer. That’s where you get decimated. We did that. We allowed that thing to happen.

David is David. There’s a good part of David. There’s really a good guy inside all of that. But, David is David, and we didn’t have anyone calling the shots. And after Monterey was where we let Jim Dickson go. There was this underlying tension, but it was a great festival.

At Monterey I knew of Ravi Shankar through World Pacific and Jim Dickson. I saw his set it was dead quiet. You could hear a pin drop. We were all mesmerized by sitar music.

Mike Clarke and I on the early Byrds tours, we used to take battery-operated tape recorders and loved listening to R&B and blues. One night at Ciro’s Mike played drums for Major Lance when his drummer didn’t show. And his hair is processed, and he turned around, “Hey drumma. Thanks man. Good job. Six bucks!”

Q: Tell me about Otis Redding at Monterey.

A: I remember watching Otis at Monterey… I can’t compare it to anyone, even my brief viewing of the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. They were so good but they had to keep stopping the show. Screams, but they were so tight. Otis Redding… It was like… I remember watching Otis Redding and I had seen Sam & Dave at the Whisky with Michael Clarke. We sat down with Otis and he bought us a drink. Sweet man. And that was just a whole other level of professionalism.

Harvey. We took everything so laissez faire out here. We weren’t entertainers. You follow? We weren’t supposed to be a Las Vegas act. But that would have taken the whole mystery out of the Byrds or the Buffalo Springfield, or any of those bands. But those guys were real professionals. They moved, they danced, and went into songs. One of my favorite albums of that era, James Brown Live At The Apollo. That record is so good you’re almost there in the audience listening to that record. And, that’s how tight the Otis Redding band was at Monterey.

Q: How about the Jimi Hendrix Experience US debut?

A: Jimi Hendrix… His playing. He was so out of left field that’s what got everybody. Not the burning of the guitar. That part was minimum. Here he was getting this tone on a guitar no one has heard before. My reaction at first was that’s a lot of noise. Noel Redding was really loud and the drummer (Mitch Mitchell) was playing nine million fills. But then that guitar tone comes in. And let me be honest with you: I didn’t appreciate Jimi Hendrix until 15 years afterwards. And I started to hear the blues stuff later on he did after all the show… He was such a good player.