-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

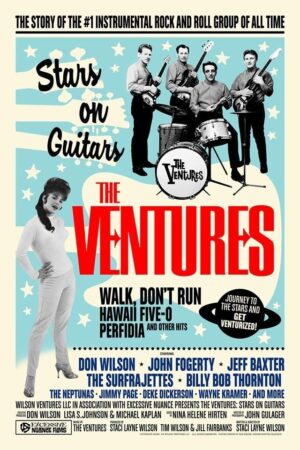

The Ventures’ first Documentary: Stars on Guitars

By Harvey Kubernik

The first-ever full length documentary chronicling the 60 year career of the Ventures, The Ventures: Stars on Guitars, debuted on DVD, Blu-ray and VOD to cable providers and streaming platforms on December 8, 2020 via Vision Films Inc.

Outlets for viewing include iTunes, Vimeo, Comcast, Spectrum, DirecTV, and Amazon. There might be a sense of wonder about how these platforms have emerged from times when TV was a luxury and now can be watched on a mobile phone. It can be traced by understanding the history of cable TV and how it helped millions of artists worldwide. Similarly, it’s the definitive history of the instrumental rock ‘n’ roll band from director Staci Layne Wilson, daughter of the Ventures’ founder Don Wilson and features 35 interview subjects. The filmic journey is told from the point of view of Wilson, the last original member of the band.

The Ventures are the bestselling instrumental rock group in history. The group has sold over 100 million records with nearly 300 different retail releases in the US and worldwide since beginning with “Walk, Don’t Run.”

The Ventures’ classic quartet lineup consisted of rhythm guitarist Wilson, bassist Bob Bogle, initially lead guitarist, Nokie Edwards, lead guitar, converted from bass, and drummer Mel Taylor. The Ventures were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2008.

It was on a construction site in Seattle, Washington, in 1959 that two guitarists, Don Wilson and Bob Bogle, decided to perform together at local sock hops, initially as the Versatones. They added a rhythm section and then became the Impacts for a very short period. Finally settling on the name “The Ventures,” they recorded two songs that Don’s mother Josie released on her Blue Horizon Records label.

The Ventures self-pressed a second single, a cover of Johnny Smith’s “Walk, Don’t Run,” a song that Don and Bob had discovered on a Chet Atkins album. “Walk, Don’t Run” was a hit single in 1960, reaching Number 2, just behind Elvis Presley’s “It’s Now or Never,” and over the last forty-six years, Wilson and his partner Bogle have subsequently recorded 250 albums and sold 100 million records, 50 million of them just in Japan.

Over the decades the Ventures’ studio and concert lineup included Don Wilson, Bob Bogle, drummers Mel and Leon Taylor, guitarists Nokie Edwards, Gerry McGee, Bob Spalding, Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, and keyboardist David Carr.

The late, legendary drummer Mel Taylor (Leon’s father), who started out playing and recording with Buck Owens and also anchored the rhythm section on the seminal hits “Monster Mash” (Bobby “Boris” Pickett and the Crypt-Kickers) and “The Lonely Bull” (Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass) drove the Ventures beat from 1962 until his untimely passing in 1996.

The Kings of Instrumental Rock, influencing scores of musicians around the world to pick up electric guitars – they endorsed the Mosrite – and strum along to the nearest TV theme or dance craze, including many kids who bought one of their influential instructional LPs called Play Guitar with the Ventures. The group recorded five of those, which became the only instructional albums ever to appear on the US national Billboard charts.

Numerous musicians credit the Ventures with helping them learn their instrument, including Anthrax, the B-52s, Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, Dire Straits, Dave Edmunds, Marco Paroni (Adam Ant), Mick Fleetwood, Aerosmith’s Joe Perry, Johnny Ramone, Jello Biafra, Keith Moon, Gene Simmons, Jimmy Page, Toulouse Engelhardt, Jim Diamond, Chris Spedding, Insect Surfers, Black Train, Gary Pig Gold, Al Di Meola, Bruce Gary, Max Weinberg, and the Malibooz’s John Zambetti. “Everybody was influenced by The Ventures,” says Steven Van Zandt. “They were huge.”

In January 2006 the Grammy Hall of Fame added the Ventures’ “Walk, Don’t Run” to their list of the most influential songs in the history of music.

Over the last half century I saw the Ventures numerous times in concert and their television show appearances. In 2006 I interviewed Don Wilson in Burbank, California.

Don Wilson interview by Harvey Kubernik

Q: How did you find the Chet Atkins cover version of “Walk, Don’t Run?”

A: My partner Bob Bogle had a Chet Atkins album Hi Fi In Focus. And Chet had a song on it, “Walk, Don’t Run,” and we loved the melody. But Chet played it in a finger style, almost classical, almost jazz. And actually, it was written by a jazz guitarist Johnny Smith. Now, Johnny Smith’s version we never heard. But we were really enamored by that particular song. And so, we couldn’t play it like that. So, we started playing it in the clubs while we were moonlighting after our construction job. You weren’t making any money playing. You got $5.00 a night and played four hours. We played Duane Eddy and a little bit of Chuck Berry. I grew up in the 1940s and loved big band stuff. I picked up trombone and played it all the way through high school.

Q: Where was “Walk, Don’t Run” recorded?

A: Joe Boles’ studio. And prior to us he had recorded a group the Fleetwoods, “Come Softly to Me,” on his label Dolton Records. We had saved our money, and thought when we came into a recording studio we would do something different. And I did a ‘Walter Brennan’ voice in our show, and thought we would do a record like that and cut something like that. And we did. A standard rock ‘n’ roll song, make a stop, I’d say something, so the “Walter” voice. I think we pressed 500 of those and I think we still had 450 of them.

Then, we started playing “Walk, Don’t Run” in these clubs we were playing in and people would come up to us and say, “What was the name of that? The song you played?” I’d say, “‘Walk, Don’t Run.'” And they would reply, “Would you play it again?” And we’d play it twice through the night because we knew we’d had something.

The audience reaction didn’t really influence the arrangement or tempo of the song, but it evolved somehow. We did two, three or four other instrumentals, like a Duane Eddy, but also something we wrote ourselves. I would say it was about 50 per cent vocals and 50 per cent instrumentals. After “Walk, Don’t Run” was requested so many times, people would come up to us and say “Why don’t you record that?” “You think so?” And we did.

Not very many takes. Two-track Ampex. You’d have the bass and the drum on one track, and the lead and the rhythm on the other. So you’d have a pretty easy mix. (laughs). But, Joe Boles was very good at getting it right to begin with, even two-track. So he did a good job with ‘Walk, Don’t Run,’ even though you have a bass and drum on one, you’d better equalize them because you’re stuck with that.

Q: And since you had a balance of all the instruments on that record, it seems the lead guitar since has always been out front on the mix or featured a little more loudly sonically, not even counting the lead guitarist in concert situations.

A: That’s very true. (laughs). Our recording was different. We had four pieces. And I told them, “I want to hear everyone of them.” And the way it worked out is that you do hear every instrument. You hear the bass, you hear the rhythm, you hear the lead and you hear the drums.

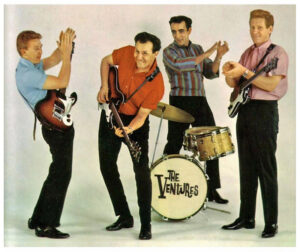

The early Ventures. EMI Records Ltd.

Q: How did the record breakout in Seattle?

A: As a matter of fact, we befriended a deejay, Pat O’Day, who just came from out of town. And he was a deejay for a very small station, and these were the only people who would talk to you. You could never get to the big station. “Who are you?” As luck would have it, Pat went to the biggest station in town, KJR. If it were not for him we might not have gotten that first record played. What Pat would do was use songs as “news kickers,” and take a song, and they had the news five minutes before the hour. And he would play a song, and not say who it was or who it is, and this is how they would find out if the audience, the listeners would like that song. And, when “Walk, Don’t Run” was played the switchboard lit up. And Pat didn’t have a piece of the record! (laughs).

So, Bob Reisdorf who had Dalton Records in Seattle heard it, he had the Fleetwoods, and he forgot that we had already brought “Walk, Don’t Run” to him four months earlier, and he passed. No one wanted the record. We went around trying to sell ourselves, and with help from my mother we started the Blue Horizon Records label, and did a previous 45, “Cookies and Coke” b/w “The Real McCoy.” Then later we pressed up “Walk, Don’t Run.”

So, Pat played it as a “news kicker” and it immediately went to number one. Three weeks. Then, Bob Reisdorf called from Dalton, who called the station, “Who is that and where are they from?” And Pat said “They are local. They live here.” Bob said, “That’s a natural, I want to talk to them.” Didn’t even remember we were in earlier playing it for him. So, he liked it before he heard it on the radio. The song wasn’t an immediate hit somebody thing.

Years later, we were out touring and the songwriter, Johnny Smith wanted us to come over and had lunch. He was making a few schekels on that. (laughs). He said to me, “If you hadn’t called that ‘Walk, Don’t Run’ I might not have recognized it.” That’s what he told me. That melody is so unique.

Q: “Walk, Don’t Run” then become a huge national and international hit?

A: We signed to Dalton, who was distributed by Liberty Records, and Bob Reisdorf was told by Liberty head Al Bennett “I don’t think it’s a hit.” And, Bob said, “I’ll guarantee it. If it loses money I’ll pay it.” “OK. If you want to make that deal that’s fine by me.” And it started climbing up the chart and went to number 2 in the nation.

Q: When drummer Mel Taylor joined the band in 1962, after your sixth album, he had already played on “Alley Oop” by the Hollywood Argyles, “Monster Mash” from Bobby Boris Pickett, and “The Lonely Bull,” the huge hit instrumental by Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass. Mel really brought a lot to the Ventures after joining when drummer Howie Johnson had to leave the band in 1962 after injuries from a traffic accident.

A: Well, in 1962, for one thing, we needed a drummer. We listened to Mel play one night at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood. That’s where we met him. But he was ‘Gene Krupa School,’ and played a lot of different things that most rock drummers didn’t play at the time. And we wanted him to join.

We had chemistry with Mel. It worked very well. He just stepped right in and we got along great. It’s important to that as far as I’m concerned you like the person you are working with. There’s a lot of groups who stay together and they are not happy with each other or ride in the same car. We were always good friends, and go out for dinner.

Luckily, we were smart along the way, and picked up ways of picking up vocals putting them into instrumentals. And ‘Venturising’ them, if you will. That was for band survival and for selling albums, too.

Q: Where did the concept come from where you and the group started recording and covering television and movie songs that were included in albums and your repertoire? Like “Batman” and “James Bond.”

A: If you play “Walk, Don’t Run” all the time, it’s just not gonna happen. We were looking for anything we could do, and those TV themes were mostly instrumental songs, 9 out of 10. That was a natural for us to go on instrumentally. And the songs could work without the visual. They were cinematic in nature, and minor keys we love. And that’s one of the reasons we got so popular in Japan. Minor keys are very prominent in Japanese music. And, there was no language barrier.

Our agent Tats Nakashima told us, “Your music is intimate, and people want to see you play it. I could put you in a ball park right now but listen to me, I don’t want to. I think you guys need to play places that hold no more than 5,000 or 6,000 people.” And there were venues all over the place like that.

When we came back in 1964 to Japan we played places that held 4,000 people, and played three times a day there and they were lined up five a breast around the block. Now we’ve been stuck with that (laughs). One year we did 108 concerts in 78 days. We ate Kobe beef and raw fish before a lot of people. I love it.

When we hit, teenagers were ready to play guitar and we just brought it to them. We went back to Japan after the Beatles played there. At first I wasn’t totally into them, it was a little bubblegum. As it went on I recognized their multiple talents, their arrangements and their vocal arrangements, and I thought George Harrison was a good guitarist. Good tone. He cited us in an interview.

I think that our early learning and our musical appreciation, even before we picked up guitars, were quite different from somebody who picks up a guitar and has only heard and only appreciates rock ‘n’ roll.

We go back to Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Jerry Vale, so many of these people that we really respected. And we learned those kinds of songs. We learned tunes like ‘Stardust’ after we really started playing, and probably playing not the most perfect chords but good enough. But we were very conscious of playing something that sounded not right. There could have been better chords, no doubt about it, but they weren’t bad chords. I’ve heard a lot of that. And we’d modulate – change keys – in our records. Modulating. We’ve done that a lot of times. You don’t want the damn thing to get boring.

We had always felt we were a good combination of ears. What I hear, Bob doesn’t hear. And what Bob might hear, I don’t hear. We were basically producing our own things. Most of our producers let us have our head. Neither Nokie nor Gerry McGee plays heavy. They play very light, using their fingers and thumb picks. Bob Bogle, who is really the Ventures’ sound of “Walk, Don’t Run,” “Perfidia,” and “Blue Moon,” the very first thing, plays with a heavy pick, but a great feel. But I still play the same as I would play anyway. I do what I want and I have a good feel for it. If I’m playing an acoustic guitar behind Gerry, I try and be as pretty as I can be. The reason we get along so well is because we don’t step on each other’s toes.

Q: Tell me about your concepts and philosophy regarding the use of vibrato and the tremolo bar also distinguished you from everyone.

A: Yes. Well, you know, there’s a very simple story to that. When Bob and I started, there were not really four-piece bands. You either had a saxophone or a piano. Two guitars, a bass and a drum. You need a piano or a saxophone. We didn’t know a drummer or a saxophone player. So, he and I when we started learning, I played very percussion rhythm, and he played with a vibrato, and coming to certain notes with a chord to make the sound even more full.

So the two of us together tried to make up for drum, piano or whatever else. And the whole thing was when we did get a drummer and a bass player that stuck with us. That was our style and the way we played. A lot of people come up and say “How do you get that sound?” Well, it’s not a matter of getting it. That’s what we do.

Q: Your Ventures In Space is very popular. It was one of Keith Moon’s favorite all time discs. He told me his first group was the Beachcombers and that he learned to play along with the pedal steel on that LP. No gimmicks.

A: That’s true. I’m surprised, but many followers of the Ventures, it is their favorite album. I don’t know if it has anything to do with not using anything electronic. We had a steel guitar player, Red Rhodes, he was absolutely great, and he put the first fuzz tone together. He owned a couple of equipment patents and he could play anything. But, using his steel guitar, and all the things he could come up with sounds, and all the sounds that we could come up with, and we tried, we accomplished, using no electronic at all. I think that impressed a lot of players.

Q: One of the most popular albums is your Play Guitar With The Ventures. The impact of that album is monumental with a great package with an instructional booklet.

A: Thank you, the first and only since that ever hit the charts. An instruction album that hit the charts and we had five of them. At one time we had five albums in the Top 100 at one time that hit the charts like Bobby Vee Meets The Ventures, and a country thing. Someone came in with an idea for an instructional album and that it would be good for us. We didn’t mind giving some secrets away. We’re pompous enough to think that nobody is gonna cop our sound regardless of what we tell them. I think it helped a lot of guitar players and they still come up to me and say “I learned to play off that album.”

Q: Guitarist Gerry McGee first came along in 1968, added something to the lineup. He’s on the early Monkees recordings and Delaney, Bonnie & Friends. I saw him blow an audience away in LA when he subbed for Henry Vestine in Canned Heat at a New Years’ Eve 1969 show at the Shrine Exposition Hall.

A: He can play anything. He shows up and plays his tail off and he’s got a feel that won’t quit. The tempos are faster on stage. I can remember the first time we played on stage in Japan. I can’t even believe how fast those songs were. They’re triple out of nerves. Trying to satisfy, not drag anything and we overdid it.

Q: One other aspect of the Ventures music is how your recordings continually are in movies and television shows like Hawaii Five-0.

A: Mel Taylor knew an engineer he worked with a lot named Ted Keep. He did the engineering for that TV show. Source music. He came to Mel and said, “They are starting this show and it’s been on for a month and the writer/composer, Mort Stevens only has a thirty second version of it and he does not plan to do a regular commercial release, and I think you guys should come in and do it.”

So we did. The record company hired 35 pieces, all brass, and we copied his version but with a guitar lead over the top. And his version did not have that.

We put it out in July 1968 and no one would play it. Then the show started getting better, but we still weren’t getting any airplay. So we hired an independent promotion man. He was real good and a go-getter. No one was promoting it and we said this is good and used our own money. We bit the bullet for a month or six weeks. Then the show’s scripts got better and then he got it played and to number one in one city. In Honolulu!

Anyway, he happened to know somebody who was a deejay who then became the program manager in Sacramento, California, and he started to play it as a favor to this guy. And it went to number one and it started spreading everywhere and it took seven months.

Q: Does it ever get tired or predictable that you are now in decades of playing “Walk, Don’t Run” nightly. I know people are paying money and want to hear it. Are you trapped by your past or are you in conflict about repertoire?

A: Never. I love to play it. We all have no qualms about playing it over and over. Now, Nokie Edwards quit, more than once, owing a little to “I’m so tired of playing those songs.” Bob and I, along with Mel, we know the audience loves it and want to hear it. We enjoy playing. I love to see the faces when we are playing “Walk, Don’t Run.”

Q: Jimi Hendrix was from Seattle. He saw the Wailers live, and Dick Dale at least a couple of times, too and heard the Ventures during 1960-1962.

A: I wore out his first album with “Hey Joe,” “Foxy Lady” and “Fire.”

When we first started in 1960, songs were 2:20, “Walk, Don’t Run,” and “Hawaii Five-O” is 1:50. In 1960-1965, if you played a song longer than 2:20 most disc jockeys wouldn’t play it, for a single. Then later in 1967 and ’68 Hendrix took it into a whole other world. He was amazing to watch. I did see him play live a couple of times in Seattle, probably 1967. ’68… Blew my mind… Amazing. I think it was his technique, and the way he hardly ever looked at the neck of the guitar. It was like he was in another world and playing those things you shouldn’t hear from a guitar. I think he was an innovator.

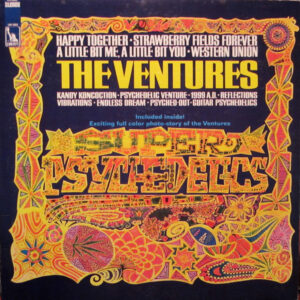

Q: Jimi was into science fiction. The Ventures even did psychedelic and space-titled long players.

A: In early ’67, a local LA deejay, The Real Don Steele on KHJ came to us and said, “There’s something coming up called psychedelic and you guys should get on that right away because it’s really gonna be something.” OK.

So we did the Super Psychedelic album released in June of ’67. We stretched out on that album. I really like it. We were older than the other psychedelic bands, wore velours and our hair was shorter. Man, red blazers, black ties, and white bucks. Drummer Keith Moon of the Who decades ago cited Ventures in Space.

Q: Man, you must have met every guitar geek on the planet digging your action.

A: For sure, for sure. They initially chose, or still utilize a Mosrite because of us. You put a Mosrite guitar out without the Ventures name what do you got? They were impressed and it had our name.

The most interesting one lately is Al Di Meloa who told me he learned to play off our stuff and also the garage bands. Even drummers we have influenced. At NAMM show I saw Mick Fleetwood and he came over. On The Johnny Carson Show many years ago, he was asked his early influences, and the first thing that came out of his mouth was “The Ventures.” And I reminded him of that. (laughs).

Q: I know some real major guitarists that play and are well-known global performers who acknowledge your influence.

A: Here’s a good story. We’re playing the House of Blues a few years ago. Aerosmith came to see us play, and sat at table near my family and friends. My son recognized Steven Tyler and somebody came up to them and said, “You guys are legends.” And Steven Tyler pointed to us and said, “No. Those guys are legends.” Now that’s a compliment. Two years ago I’m in Japan, or last summer. Aerosmith is playing the Tokyo Dome. Now, I don’t know Joe Perry. But he and I are waiting for a train. He looks at me and says “Are you a musician?” “Yeah.” And he said, “Who are you with?” “The Ventures.” “The Ventures! Can I get a picture” “Sure.” And he calls his manager and says, “Get over here. This is history!”

I talked to him all the way on the train. I had no idea they had an autobiography out. So anyway, he says, “I’m gonna get you tickets to our show and to come backstage.” “OK.”

My wife and I went backstage with Leon our drummer. Joe then said it was an honor to stand in front of me and talk. And then he’s on stage he said, “My teacher is out there.” He introduced and brought me out. Everybody knows the Ventures in Japan. The place went crazy and I didn’t even have to play. (laughs).

Harvey Kubernik 2020

A Ventures playlist:

https://open.spotify.com/artist/2GaayiIs1kcyNqRXQuzp35

In 1964 Harvey Kubernik was the drummer/percussionist of a very short-lived surf instrumental group called the Riptides. In the late seventies he provided handclaps and percussion on recording sessions of the Runaways, the Surf Punks, the Ramones, the Paley Brothers and Leonard Cohen.

Kubernik is the author of 19 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published the Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz. The duo for the same publisher in September 2021 have written a book on Jimi Hendrix. In 2019, The National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC have asked Harvey to pen an essay on the landmark The Band album, which celebrated a 50th anniversary edition in 2019. Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown appears in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada. Harvey joined a distinguished lineup which includes LeRoi Jones, Johnny Otis, Ellen Willis, Nat Hentoff, Jerry Wexler, Jim Delehant, Ralph J Gleason, Greil Marcus, and Cameron Crowe.

Harvey’s 1996 interview with poet/author Allen Ginsberg was published in Conversations With Allen Ginsberg, edited by David Stephen Calonne for the University Press of Mississippi in their 2019 Literary Conversations Series. This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century. During 2020 Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted this spring on the EPIX cable TV channel In late summer 2020, Otherworld Cottage Industries published Harvey’s film and music study, Docs That Rock, Music That Matter.