-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers -

Davy Jones 1945-2012

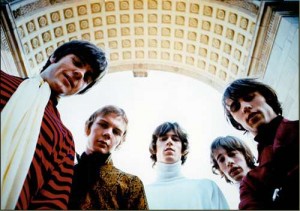

David Thomas “The Manchester Cowboy” Jones’ first love was jockeying, a fitting choice for the height-challenged heartthrob, until the stage called him. A later American promo tour for Oliver! fated him with the divinity to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show the monumental date of February 9, 1964. From side-stage a teenaged Jones was bewitched by the Beatles making their American debut and found truly what pie he was a piece of.

Of the Monkees remarked Davy they were a “good garage band,” and perhaps that’s what endears them to UT readers, even those not hip to poppin’ bubblegum. While some of the Prefab Four later divorced themselves from the entity due to its synthetic, machine-made product value, Jones trudged along living and singing the hell out of those hits until he tragically left us. Those inescapable jams of childhood made me a believer, and I shall be to until the day I expire. Godspeed, King of the Wild Tambourine.

Below Michael Lynch pours his Monkee-lovin’ heart out, and a playlist to partake in compiled from Michael’s references and a few of my own. (jeremy nobody, esq.)

The short Monkee. The English Monkee. The cute Monkee. The one who got the girls. The one who played tambourine. The one who later called on Marcia Brady. However people remember Davy Jones, the point is, everybody will remember him.

An all-around entertainer, Davy already had racked up some success as an actor before Screen Gems made a Monkee out of him, most notably his Tony-nominated portrayal of the Artful Dodger in the Broadway production of Oliver! The success of Oliver! led him to try milking his teen appeal through American television guest spots (Ben Casey and Farmer’s Daughter) and, of course, records. 1965 yielded an album, David Jones, and three singles for Colpix, only one of which (“What Are We Going to Do”) charted, and at only #93. His luck changed that autumn when he was chosen as one of the stars of an impending sitcom about “four insane boys.”

Pete Cosey 1943-2012

By Eric Colin Reidelberger

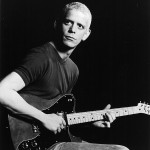

Few guitarists are more underappreciated than the big man, Pete Cosey. An incomparable aural trailblazer and avid woodshedder who blew the doors off every entrance he made. As a wide-open player who employed many musical “systems” (as he called them) he preferred bridges to barriers and played with jazz, country, frat rock and blues bands alike, when that practice was purely unheard. He was a session man, manipulator of chord progressions and such a wild experimentalist that Miles Davis once told him that he “…wrote differently than anyone he’d heard.” It’s with hope that there are more extant sides to arrive from this mountain of a man, both physically and as an institution. Below Sir Eric Colin gives lip service to the man’s history and prowess, plus I’ve included a playlist of some of Cosey’s contributions. What’s your fave-rave? (jeremy nobody, esq.)

Pete Cosey’s name might not have been at the tip of everyone’s tongue, but if you owned any records on the Chess label from the late ’60s or dug your heels into any of Miles Davis’ grand wigouts, then chances are you are probably familiar with his handiwork. A sonic adventurer that boldly went where only a few dare tread, finding the continuity between Jazz, Funk and Psychedelic Rock and trailblazing his own pathway to the nether regions.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943 and after living his teenage years in Phoenix, Arizona, Pete cut his teeth as a session player in the ’60s/early ’70s back in Chicago for Chess Records. He played on numerous sessions (often uncredited) by artists such as Etta James, Chuck Berry, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, Rotary Connection and the polarized electric periods of both Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters. Adding a surfeit of effects, including a wonderful preponderance of wah-wah/fuzz acrobatics, Pete managed to completely horrify blues purists in one fell swoop, and gather quite an audience of heads who would go on to champion his bold explorations in the years to come.

Cosey was a truly inventive and original player who was obviously influenced by Hendrix’s stylings, but taking the proceedings into an almost unhinged free jazz territory akin to similar giant steps taken by fellow traveler Sonny Sharrock. He was an embryonic member of Chicago Afro Funk behemoths The Pharoahs who later became the seeds of Earth, Wind & Fire, as well as exploring some spiritual journeys with Philip Cohran. Pete is best remembered for the four albums he played on under Miles Davis’ solid-band leading hand: Get Up With It, Pangea, Agharta and Dark Magus.

It is here and in such stellar company that his creative being was given the proper chance to flourish; often pushing the music (and perhaps) the musicians into fever pitch territory.

After the breakup of the Miles band in 1975, Pete kept a relatively low profile, only rearing his head here and there in the years afterwards, most notably playing on the title track to Herbie Hancock’s Future Shock. On May 30, 2012 in Chicago, after complications with surgery, the world lost yet another major musical talent who really wasn’t given the proper credit of the true sonic pioneer he was.

From our current issue, Ugly Things #33, jeremy nobody, esq. reviews one of the grand experiments Cosey contributed to: This Is Howlin’ Wolf’s New Album: https://ugly-things.com/reviews/albums/

Robin Gibb 1949-2012

By Collin Makamson

By the general populace the Bee Gees are known as little more than disco fadsters, but all good boys know the brothers Gibb carried much more weight than all that. In mid-’60s Australia they racked up hits as an Everly Brothers-styled singing group and made the leap to England in the midst of all its technicolor glory, there creating some of the most monumental album-sized statements of the period. As group member and solo artist Robin made grand moves in his late teens many grown men never aspire to, with a catalogue of pathos-drenched, near-strained, soulful vocals that laced hits and deep album cuts alike. He was the wit, dry humor and heart of the Bee Gees; akin to the Monkees’ Nesmith or Beatles’ Lennon. Recently cancer that was long-battled shuffled him off to join his two passed brothers (fraternal twin Maurice and younger brother Andy), aged 62, but like the man said himself:

“Art is about forever, beauty and immortality. I don’t think of death. That’s for other people.”

Below Collin Makamson ruminates on the importance of Robin and sermonizes on the mathematics of artistic repeat-returns…

(jeremy nobody, esq.)

In my opinion, the success of any work of art is not measured by the amount of pretty words and blue ribbons which one can neatly hang upon it, but rather upon the number of return trips it inspires ‘to the sources.’ That’s what good art does: that’s its function. That’s what good music does as well. It inspires a missionary zeal compounded with a cartographer’s hate of blank spaces on a map. It invites obsession inside as a guest and sets an empty plate, sustaining itself solely on the deep resonance of the initial aesthetic shockwave. That’s what Robin Gibb’s music does and continues to do in me and thousands of others and, as such, this is not an obituary, a eulogy, a bike or a pipebomb. It’s a signpost and a sermon.

Other things this is not. NOT an ephemeral by-the-numbers bio-piece. NOT a condescending blow-by-blow discographical romp or even an anatomical celebration of Robin’s heartbreaking voice: the most benign throat-lump inducer this side of Roy Orbison.

Rather, it is a sticking to my original thesis and guns. Fine if you forgot it already. The best art and the best music compels one to track down and follow its influences, wind its tributaries, know its hidden places, swallow its bread-crumbs, know its markings. Like Lewis & Clarke or Columbus in reverse. However, the Beaux-arts also teach one to remain mindful of similar ripples, dispersions and fellow traveling waves dominoeing outward that, in turn, may carry new influences and sediment to add to the original.

Perhaps the best piece of news of all for pilgrims set out upon these trails is that despite rumors of the frontier’s closure or hints that the promontory-peak of the sublime melting glacier of humanity’s divine input might already have been summited, take comfort in the fact that there always remains more to digest and explore.

And don’t take my word for it; take the words of another great artist whose works are still moving.

“It is not down in any map. True places never are.”

Robin Gibb will be missed. Here are some places that his music took me, both new and old.

Roots, fruits and CM’s self-designated finest vocal by Robin follow. Use the arrow button on the lower-right portion of the YouTube box to scroll through the selections, or listen to them continuously by pressing play.

Also find below an Ugly Things exclusive of Skooshny covering Robin’s “Saved by the Bell” which at this time goes unreleased.