-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

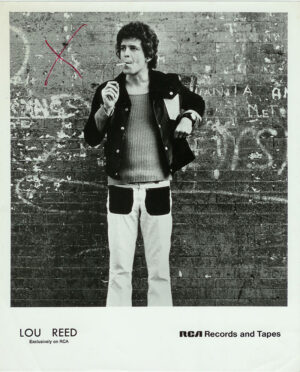

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal persona which would typecast Lou for years, was “I’m So Free.” A weedy platform-hopping rocker, it’s always sounded to me like filler with slapdash lyrics. But, not so long ago, I started to wonder about the “Saint Germaine” Lou references in the song. Up until that point, I’d always assumed he was just one of the real-life Warhol superstars or invented characters with whom Lou peopled the songs on the album:

Oh please, Saint Germaine

I have come this way

Do you remember the shape I was in

I had horns and fins

I’m so free

I’m so free

Do you remember the silver walks

You used to shiver and I used to talk

Then we went down to Times Square

And ever since I’ve been hangin’ round there

It turns out that Saint Germain—as the name is commonly spelled—was an 18th century composer and musician revered by Theosophists as also an alchemist and great spiritual master. Theosophists follow Theosophy, the religious, occultist group co-founded by mystic, author, and trickster Madame Blavatsky in New York in 1875. So, what’s Saint Germain doing on an album that has defined a certain kind of sexually fluid, narcotically informed and ham-fistedly decadent rock and roll for decades? And why does it read like Lou is sending up a prayer to him?

The answer, I believe, lies in the fact that, although, as it’s commonly understood, alchemy refers to the transmutation of metals and the fabrication of gold, for Theosophists there’s a spiritual dimension to the practice. Saint Germain was a spiritual alchemist. Spiritual Alchemy is the transmutation of man’s animal nature into the Higher Self. In “I’m So Free,” Lou, who had “horns and fins,” animal attributes, sounds like he’s begging to be transformed. To the accepted meanings of Transformer, spanning transforming underground cult hero Lou into a pop star and blurring sexual identity —“shaved her legs and then he was a she”—among others, I would say we can add spiritual transformation. But that still doesn’t explain how Lou even knew about Saint Germain.

Before we go on, I should mention that, in an earlier version of the song recorded in 1970 in Lou’s bedroom at his parents’ house on Long Island after he’d left the Velvet Underground, he sings “Do you remember the shape I was in/I was covered in sin,” making the lyric feel more about redemption. But by October 27, 1971, when the sessions gathered on I’m So Free: The 1971 RCA Demos were recorded, the line had become “I had horns and fins.” Lou already had transformation on his mind.

Billy was a good friend of mine

A clue to as to why Lou mentions Saint Germain is buried in the verse that begins “Do you remember the silver walks.” My gut feeling is that this refers to Billy Linich AKA Billy Name. Name was part of the group of avant-garde musicians that gathered around drone-meister La Monte Young in the late 1950s—in Billy’s own words, he was a “human drone”—before becoming court photographer to Andy Warhol’s Factory. Lou and Name were great friends, occasional lovers, and, for a time, fellow methamphetamine devotees. Lou adored Name. Speaking on radio WBCN-FM in Boston in early March 1969, the month the Velvets’ third album was released, he describes Name as “divinity in action on earth” and, as the photographer of the cover of the third album, taking pictures that are “unspeakably beautiful…pure space, for people who have one foot on earth and another foot on Venus.” When Lou liked someone, he gushed.

Name was responsible for silverizing Warhol’s Factory with the tinfoil he slapped on nearly every surface. Talking and shivering suggest speeding. More significantly for our quest to explain the appearance of Saint Germain in the song, Lou also claimed to have introduced Name to the work of Theosophical writer and teacher Alice Bailey:

“A friend of mine got so far into it he locked himself in a closet for two years and never came out and I know exactly what he was doing because I was one of the few people he let in, visited him periodically, checked he was alive and he explained to me what he was doing and I know what…because I was the one who started him on the books [of Alice Bailey] and he went through all fifteen volumes and when you follow that book, it teaches you, you know the seven centers of the body and moving the energy. It can be dangerous. Meditation can be dangerous if it’s not done correctly…You can do things that aren’t right, but he was literally going off his body cell by cell. It was really something to see.”

According to an interview Name gave to UK newspaper The Guardian in 2015, he shut himself away for about a year, but the reason was rather more prosaic. “I didn’t really relate to the Factory any more…I’d have visitors like Lou Reed, but I really wanted to get my negatives in order and that took a lot of time.”

Name finally left the Factory in 1970 because, as he told author of the piece Sean O’Hagan, he was “saturated by silver.” But, all those years later, looking back on his time in the New York avant-garde from a hospital bed in Poughkeepsie, Name said, “I miss the times when I was really free.”

Jack Kerouac: Poetry for the Beat Generation / Blues and Haikus

By Harvey Kubernik

Jack Kerouac was a leading prose stylist of the beat movement in literature, author of On the Road, The Dharma Bums, and many other celebrated works. On December 9, 2022, Real Gone Music will release 100th birthday vinyl editions of the author’s first two spoken word albums. Poetry for the Beat Generation and Blues and Haikus.

Issued in 1959, Poetry for the Beat Generation was Kerouac’s recording debut. As the Real Gone Music press release explains, “Kerouac had completely bombed in his first set during a 1957 engagement at the Village Vanguard when TV personality, comedian, and musician Steve Allen volunteered to accompany him on piano during the second. The results were so impressive that legendary engineer Bob Thiele then brought the duo into the studio to record an album for Dot Records. In true, stream-of consciousness, beat fashion, the entire album was cut in one session with one take for each track, Allen’s piano weaving in and out and occasionally commenting on Kerouac’s verbal riffs to great effect.”

Dot President Randy Wood subsequently rejected the master due to its then-daring language and subject matter.

Only 100 now-very-valuable promo copies were made. Thiele then founded Hanover Records with Allen and released the record in 1959. The Real Gone title due in December will be pressed on milky clear vinyl.

Thiele also produced Kerouac’s second album, Blues and Haikus, issued on Hanover later the same year. But this time, he was accompanied by two jazz legends, saxmen Al Cohn and Zoot Sims.

“Big-time post-bop saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims made their bones in Woody Herman’s band, and here they provide effective counterpoint commentary to Kerouac’s readings,” explains the bio. “As for those who approach this release from a more literary angle, Blues and Haikus reflects Kerouac’s interest in Eastern religion and meditative practices as expressed in his novel The Dharma Bums as opposed to the more On the Road-like exultations of Poetry for the Beat Generation.

“But whatever your interest, boppish or bookish, Blues and Haikus is an essential document from one of our most iconic American authors, and, after listening to this album, one thing is for sure: no one is having a better time at this recording session than Kerouac himself! On the occasion of Kerouac’s 100th birthday year, this cult classic record comes in tobacco tan vinyl”

##

“When I had my record shop in the middle of Melbourne, Australia in the early 1970s next door to me was a book shop where an old Beat poet worked as the sales assistant,” recalled writer and musician, David N. Pepperell. “I found out he actually had copies of the two Jack Kerouac spoken word LP’s – impossibly rare and hard to get – and asked him to loan them to me for taping which he very kindly did.

“But this time I had read all of Jack’s books and they had vindicated my long held and much-dismissed idea that it was not necessary to try to fit into the world, that the world needed to fit into us. Jack’s wonderful novels extolled such a freedom and showed me that I was not alone in feeling an alien in this conservative world and that I had allies in my attempt to remain myself without having to compromise my beliefs to make my way forward. The marvelous writing of his books, the sensitivity to music and art and the love Jack had for all people moved me enormously and I decided if I did become a writer I would try and write like him or at least write words that he would approve of and agree with.

“Simply I became a Beat writer and have been so for the past 55 years. I dearly loved Jack’s writing but I was unprepared for the thrill of hearing his voice reading his work with such alacrity and conviction. This gave me a whole new view of him, his writing and his philosophy of life.

“These recordings – with fine musicians like Steve Allen and Zoot Sims and Al Cohn – are precious artefacts in the culture of literature and it is wonderful that they are again available to a New Generation seeking the same truths that Jack always told and always lived.

“Nice to have the records back on the format – plastic vinyl – that Jack originally recorded it on too!”

“Understanding Jack Kerouac and his writing begins with acknowledging his profound relationship with jazz,” explained historian Dennis McNally, author of Desolate Angel: Jack Kerouac, The Beat Generation & America.

“His best writing springs from the same improvisational — ‘composition on the fly’ — roots as jazz. The deep form that he sought was in the same realm as the sound that Charlie Parker explored. To boot, Kerouac had a beautiful reading voice. Paired with a fine pianist like Steve Allen, he delivered the goods.”

“Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and October in the Railroad Earth are rhapsodies,” offered actor/poet Harry E. Northup. “His prose is like the rolling hills & the open road America; you hear America in his singing, his search for a home. He wrote, that’s what he did. The men in the car in On the Road lived outside society as they crisscrossed America. They wrote, that’s what they lived for, not conformity.

“I read On the Road, when I was 16, in 1957, when it came out. I had begun hitchhiking when I was 11 and when I was 16, I hitchhiked from Sioux Ordnance Depot to Sidney, in western Nebraska many times. On the Road set my life ablaze with a yearning to burn, as Kerouac said, to blaze away. Did Kerouac blaze? He blazed! And gave us a taste of Romanticism.”

“Back in the late ’50s as I was completing my high school years, a too-hip classmate of mine tipped me to On the Road, enthused writer/author/reggae scholar, Roger Steffens.

“An avid reader, I devoured four or five books a week in my youth, but I had never encountered prose like Kerouac’s. Raised in Brooklyn, and North Jersey, I had no geographic knowledge outside of that cramped terrain, and when the opportunity arose, I bought a ’65 yellow Mustang and embarked on a speaking tour of the Midwest, reading Beat poetry to high school classes in a show called Poetry for People Who Hate Poetry. The Beats just felt good in my mouth, and it was thanks to Kerouac that I discovered them too.”

##

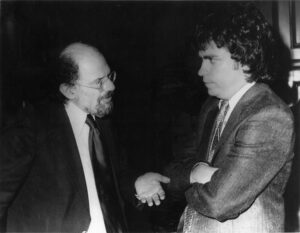

Harvey Kubernik and Ray Manzarek, 1992. (Photo: Heather Harris)

When I first met and interviewed Ray Manzarek co-founder of the Doors in 1974, he exclaimed, “If Jack Kerouac had never written On the Road the Doors would never have existed.”

Over the last five decades, Ray and I discussed Kerouac, the beat generation, and the impact on the Doors.

“My wife Dorothy and I went up to San Francisco in approximately 1963, during a spring break from UCLA. We tried to get up to San Francisco as much as possible. So, we went up to San Francisco and there was a poetry reading going on featuring Lew Welch, who had just come out of the forest after being a hermit for the last three or four years. He was just charged and wired out of his mind. Gary Snyder had just come back from Japan, wearing his Japanese schoolboy suit. He was mellow and tranquil. And Phillip Whalen read and was just a house of fire. Words were coming out of his mouth so fast you had to listen so closely.

“Somebody in the audience yelled, ‘speak slower!’ And Phillip Whalen stopped for a second after he heard that and said ‘listen faster! There were 2,000 people in the audience, man.”

We talked about the filmic influences on the Doors and their beatific recording, “L.A. Woman.”

“The Doors were part of Raymond Chandler, John Fante, Dalton Trumbo. It was the dark streets and The Day Of The Locust, ya know. Miss Lonelyhearts. That’s where the Doors come from. ‘L.A. Woman’ is just a fast L.A. kick ass freeway driving song in the key of A with barely any chord changes at all. And it just goes. It’s like Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg heading from Los Angeles up to Bakersfield on the 5 Freeway. Let’s go, man.”

In 2001, Manzarek reminisced about Jim Morrison and his poetry album An American Prayer.

“It was the first full-length rock ‘n roll poetry record. Back in the ‘50s, we used to get spoken word records by everybody, Dylan Thomas, E.E. Cummings, Kenneth Patchen. This is entirely different. I saw Jim’s words before he started writing songs. So, when you see his words on the page that’s poetry. I always thought of Jim as a good poet. But when he started writing songs, then everything became verse, chorus, verse and chorus. Really tight, and it was a whole other ball game. He put his words into an entirely different context. A musical context. A hit single in a three-minute context. I thought ‘Moonlight Drive’ was brilliant when I heard him sing it on the beach in Venice, I thought he had it.

“Lyrics are poetry. The words were well edited. Jim was good that way when it came to songs. When you are doing this written poetry, you can really stretch out and you can really expand.

“With his poetry, he’d throw this out, take this line, or two lines, but when it comes to music you gotta be very choosy because you only have a short period of time. Songs in a way, outside of like ‘The End,’ and ‘When the Music’s Over’ are sorta like haikus. The fit has to be very tight.”

In 1972 I coordinated two accredited upper division English and music curriculum courses conducted by Dr. James L. Wheeler, assistant professor in the School of Literature at San Diego State University. A story in the April 14, 1973 issue of Billboard magazine, the music trade hailed the department’s academic aim as “the world’s first university level rock studies program.”

I invited future authors publicist Sharon Lawrence and music journalist Danny Sugerman, along with singer/songwriter Carolyn Hester to speak to the class. I placed Jim Morrison’s The Lords & New Creatures on the required book list and suggested other titles, most notably, On the Road, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind, and Anthony Scaduto’s Dylan A Biography.

Around 1974 or 1975, I had two brief encounters in Hollywood with music journalist and writer, Lester Bangs, a student at SDSU during 1968-1970. It was Grelun Landon at RCA Records in Hollywood who introduced us. One was after a Mott the Hoople concert at the Hollywood Palladium. I praised Lester’s review of a Mott the Hoople LP for Creem. He was from El Cajon. We both frequented Ratner’s record shop in downtown San Diego and I already knew of his passion for Jack Kerouac. I mumbled something about appreciating his obituary on Kerouac in the November 29, 1969 Rolling Stone.

Lester immediately touted Kerouac’s On the Road and Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. In 1970, we both saw Ginsberg read his poetry at SDSU’s Aztec Bowl. Larry King was there, who later managed the Tower Records stores in San Diego and Hollywood.

##

Allen Ginsberg and Harvey Kubernik, 1982. (Photo: Suzan Carson / Courtesy Harvey Kubernik Archives)

In the mid-seventies I met Allen Ginsberg. I went with Leonard Cohen, after conducting an interview for Melody Maker, to see him read at Doug Weston’s Troubadour club in West Hollywood.

I interviewed Ginsberg at length three times in the eighties and nineties, and also co-promoted several of his Southern California readings in Los Angeles and Santa Monica. In 1982 I produced a live reading of Allen and Harold Norse at the Unitarian Church in Los Angeles.

In 1976 I provided handclaps on two tracks with deejay Rodney Bingenheimer on Cohen’s album Death of a Ladies’ Man, produced by Phil Spector at Gold Star Recording Studio. On one cut, Ginsberg and Bob Dylan join Cohen on “Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On.”

My first Ginsberg interview initially appeared in 1996 in HITS Magazine and a very short edited version was published in The Los Angeles Times Calendar section on April 7, 1997 when the daily newspaper asked me to pen one of the tribute stories on Ginsberg when he died.

When Allen passed on April 5, 1997 in New York City at his East Village loft of liver cancer and hepatitis at age 70, that evening Dylan was playing a concert in the Midlands at the Moncton Coliseum in Moncton, New Brunswick, and dedicated “Desolation Row” to Allen Ginsberg. Dylan had not been including the song in recent gigs.

During 1999, a portion of one of my Ginsberg interviews was published in The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats. In 2007 I wrote the liner notes to the first-ever CD release of Ginsberg’s Kaddish for Water Records.

“I learned a lot from William Carlos Williams, and the elders of my generation,” underlined Allen. “People who were much older than me when I was young. And that inter-generational amity is really important because it spreads myths from one generation to another of what you know, and all the techniques and the history.

“And I get the same thing whenever I get to work with younger people. And I learn from them. I don’t think I would have been singing if it wasn’t for younger Dylan. I mean he turned me on to actually singing. I remember the moment it was. It was a concert with Happy Traum that I went to and saw in Greenwich Village. I suddenly started to write my own lyrics, instead of Blake.

Allen Ginsberg, February 1967. (Photo: Roger Steffens)

“Dylan’s words were so beautiful. The first time I heard them I wept. I had come back from India, and Charlie Plymell, a poet I liked a lot in Bolinas, at a ‘Welcome Home Party’, played me. Dylan singing ‘Masters Of War’ from Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and I actually burst into tears. It was a sense that the torch had been passed to another generation. And somebody had the self-empowerment of saying, ‘I’ll Know My Song Well Before I Start Singing It.’

He spieled on the current interest in beat-inspired writers.

“The renewed interests stem from the fact that we were being more candid and truthful than most other public figures or writers at the time. We were switched over to writing a spoken idiomatic vernacular, actual American English, which turned on many generations later. Dylan said that Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues had inspired him to be a poet. That was his poetic inspiration.

“So, I think what happened is that we followed an older tradition, a lineage, of the modernists of the turn of the century continued their work into idiomatic talk and musical cadences and returned poetry back to its original sources and actual communication between people. That was picked up generation after generation up to people like U2, who are very much influenced by Burroughs in their presentation of visual material. Patti Smith, and Thurston Moore and Lee Renaldo of Sonic Youth are interested in poetry.

“Earlier, there was the poetry and music. King Pleasure, and the people who were putting together be-bop, syllable by syllable, like Lambert Ross and Hendrix. I knew them in 1948. We used to smoke pot together in the ’40s, when I knew Neal Cassidy, around Columbia when I was living on 92nd Street.

“Around 1944, ’45, Kerouac and I were listening to Symphony Sid, and I heard the whole repertoire of Thelonious Monk, ‘Round Midnight,’ ‘Ornithology’ and all that. I actually saw Charlie Parker, weekend after weekend a few years later at The Open Door. Later on, I spent an evening with him, now the Charlie Parker Place.

Allen Ginsberg, 1967. (Photo: Roger Steffens)

“Also in San Francisco, in the mid-’50s, there was a music and poetry scene. Mingus was involved with Kenneth Rexroth and Kenneth Pachen. And Fantasy records documented some of that. The Cellar in San Francisco.

“By the time I got around to getting on the radio, it was actually an AM station in Chicago with Studs Turkel; recorded the complete reading of Howl in Chicago, later used for the Fantasy record. It was broadcast censored. ’59. KPFA in the Bay Area then started broadcasting my stuff in San Francisco, a Pacifica station. Fantasy put out Howl and that got around. Then, Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, put out Kaddish. It was radio broadcast from Brandeis University.

“So, I think what happened is that we followed an older tradition, a lineage, of the modernists of the turn of the century continued their work into idiomatic talk and musical cadences and returned poetry back to its original sources and actual communication between people.

“I think you’ll find in Howl, sympathy. In fact, I remember when Kerouac was asked on the television show William F. Buckley Firing Line in the sixties what ‘Beat Generation’ meant, Kerouac said, ‘Sympathetic.’”

On Bob Dylan’s 1975-1976 semi-improvised Rolling Thunder Revue tour, Dylan performed a concert at the University of Lowell in Lowell, Massachusetts.

The following day, Dylan, Ginsberg and some band members visited Kerouac’s grave in Lowell on November 2, 1975. The trek was self-promoted, with revolving musicians making guest stops in clubs and small hall venues across the US. The road trip circus came to town, organized by Dylan’s friend Louie Kemp, with Bob Dylan assuming a role akin to Kerouac’s character Sal Paradise in On the Road.

I asked Ginsberg about Rolling Thunder and the film Renaldo & Clara culled from that expedition.

“Dylan delivers. Well, first of all, it’s Dylan extending himself to the extreme, and including all his friends and all his inspirers, and all his workable companions in a big circus going through America. A musical circus. His mother was along at one point. His kids were along at one point. His wife [Sara] was along. Joan Baez’s kid was along. So, it was this great family outing trying to hit all the small towns, originally, like in Kafka’s America. The traveling circus in Kafka’s America.

“For me it was great, and to hear Dylan so often, I was able to hear backstage, in the audience, from the side, in the wings, and go out to the furthest seats with a pass. He was at a peak of musicality and energy and inspiration. Like ‘One More Cup Of Coffee’ and ‘Idiot Wind,’ which is one of my favorite lyrics. A national lyric with its great ‘Circles around your skull . . .’ Really quite manic. It was great to see a band on a rock ‘n’ roll tour. Rolling Thunder Revue on a grand tour, and see all the work that went into it.

“Renaldo and Clara was a great artistic film that was mocked when it first came out, although it was a hit in Europe, or it was very much appreciated in Europe. Now, when people see it now, I think people will realize it was a great treasure. At first people were screaming ‘Four Hours!’ ‘What a big egotist.’ But actually it’s four hours of Dylan exploring the nature of identity of self, and pointing out there is no fixed identity. It was making a huge movie in an interesting way.”

Bob Dylan. Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, December 19, 1965. (Photo: Rodney Bingenheimer)

##

Dylan, via tour manager Bob Neuwirth, asked guitarist/arranger Mick Ronson to join the Rolling Thunder Revue. Ronson had been David Bowie’s lead guitarist in Bowie’s former band, the Spiders from Mars.

The current David Bowie documentary, Moonage Daydream, illustrates his debt and influence of Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs.

A song by Bowie, “All the Madmen,” first heard on The Man Who Sold the World, addresses Bowie’s half-brother Terry Burns and his struggles with mental illness. Bowie acknowledges Terry as the first explorer and seeker in the family.

During Bowie’s 1974 Diamond Dogs tour, I spent half an hour with David at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. We talked about beat generation literature and R&B music. We then attended an Al Green concert at the Universal Ampitheater.

I handed Bowie a paperback copy of Ann Charters’ Jack Kerouac: A Biography knowing his Spiders from Mars band name had a link to Kerouac’s On the Road: “exploding like spiders across the stars.” Charters’ book is seen by David’s hotel bedside in the Omnibus Cracked Actor 1975 UK documentary which aired on the BBC 1 channel.

Jack Kerouac also made an impression on teenage Janis Joplin, then living in Port Arthur, Texas. She attended Thomas Jefferson High School and later the University of Texas in Austin. Three of her favorite writers were Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure before she then fled to San Francisco.

“I grew up and got to see all the jazz cats in the clubs. Plus, I saw all the beatniks, and great writers and poets,” beamed Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane in a 2014 interview we did. “This is a world before 1967 and the Summer of Love. It started with the beatniks and poets.

“I think San Francisco was full of all these people who were talented and who were expressing themselves or their rights or playing music. And I think San Francisco has a lot to do with that. I don’t know if it’s the geomagnetic forces of the earth and the ocean but something went on there. It’s a lot different than the rest of the world.

“In 1965 I helped open the Matrix Club and did some booking in 1966 and ’67. People were coming in looking for places to play, the infamous Warlocks and Janis. I had an immediate influx of people.”

In a 1976 interview I conducted with Jerry Garcia inside Bill Graham’s Mill Valley residence for the now defunct Melody Maker, Jerry discussed the 1964-1976 sounds emanating from San Francisco. After the session was over, Jerry and I discussed Kerouac. I made a mental note, and had a feeling years later I’d reference Jerry and Jack’s contributions in my own nascent literary efforts.

In 1990, I was the Project Coordinator on The Jack Kerouac Collection for the Rhino/WordBeat label. I arranged for Ray Manzarek, Michael C Ford, Jerry Garcia and Michael McClure to contribute to the package booklet liner notes.

In the mid-eighties I produced spoken word and music programs with Manzarek and McClure on bookings with Charlie Haden, Paul Motian, Alan Broadbent, and the Minutemen at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica.

In our 1976 interview, Garcia said he first heard the word ‘beat generation’ in high school in San Francisco, and then a teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute told him about Kerouac’s On the Road.

In his Jack Kerouac Collection liner note contribution Garcia stated, “His way of perceiving music-the way he wrote about music and America – and the road, the romance of the American highway, it struck me. It stuck a primal chord. It felt familiar, something I wanted to join in. It wasn’t like a club, it was a way of seeing. It became so much a part of me that it’s hard to measure; I can’t separate who I am now from what I got from Kerouac. I don’t know if I would ever have had the courage or the vision to do something outside with my life – or even suspected the possibilities existed – if it weren’t for Kerouac opening those doors.”

In the product text, I wrote, “Jack Kerouac’s influence on my environment, then and now, is obvious. Kerouac’s written/verbal work helped me walk around the block so I can still cross the street seeking.”

“One of the things you could say about all the bands that came from San Francisco at that period of time was that none of them were very much alike,” stressed Garcia. “I think that the world has changed. I think the United States has changed very visibly in the last ten years. A lot of it had to do with what happened in San Francisco.

“I can’t say how or why, but I also think it’s affected everything. Just all the interest in things like ecology. All the interest in the sense of personal freedom as expressed by all kinds of movements. All these things were designed to free the human. Social overtones. All that stuff. The communal spirit. I really think the scene out here created the possibility for Woodstock to happen. The Monterey International Pop Festival. The thing, the activity, music and people. The set-up was out here.”

In Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song, he cites the Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’,” and lyricist Robert Hunter, the “in-house writer-poet, Robert Hunter, with a wide range of influences-everyone from Jack Kerouac to Rilke-and steeped in the songs of Stephen Foster.”

Kerouac’s fingerprints can also be found in dozens of recordings the last half century, including Tom Waits’ “Medley: Jack and Neal/California, Here I Come,” King Crimson’s “Neal and Jack and Me,” and 10,000 Maniac’s, “Hey Jack Kerouac.” Dylan’s “Desolation Row’ title is a nod to Kerouac’s Desolation Angels.

##

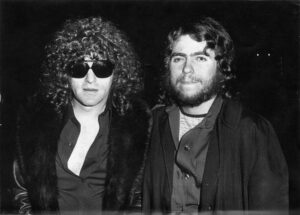

Ian Hunter and Harvey Kubernik, 1979. (Photo: Brad Elterman / Courtesy of the Harvey Kubernik Archives)

In 1978, I had a meal at Duke’s, the coffee shop at the Tropicana Hotel on Santa Monica Boulevard with record freak and sound hound, Guy Stevens. He was an avid R&B music collector, who did talent scout work at Island Records and produced albums by Mott the Hoople and the Clash.

Guy readily confessed that a Mott the Hoople track from Brain Capers, “The Wheel of the Quivering Meat Conception” was a direct homage to Kerouac’s own piece, “The Wheel of the Quivering Meat Conception.” He mentioned Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” and that he and Ian Hunter, bandleader of Mott the Hoople, were Dylan devoted fans. In fact, at the Mott the Hoople demo audition for Island records, where he was judging talent, Hunter sang a fragment of Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone,” later housed in the Mott The Hoople box set.

“It’s no secret that I’ve always acknowledged Bob Dylan as one of my heroes,” expressed Hunter in a 1998 interview we did. “Michael (Mick Ronson) always liked to go to Reno Sweeney’s (a club in New York). One night I said to Mick, ‘why don’t we go down to the Village?’

“I took him down to the Village. He’d never been there before. We went an all hell broke loose. Dylan was playing next door in a little café. Forty people in the room, and he performed what was to be the Desire album. It was great. There he was. What an electric night!

“Mick didn’t know what was going on. Bobby Neuwirth then got him the gig with the Rolling Thunder Revue. Dylan recognized me when Neuwirth told him who I was. We were introduced, and Dylan started jumping up and down saying ‘Mott The Hoople! Mott The Hoople!’ Here I was talking to Dylan, and I thought he didn’t like Mott The Hoople by the way he was acting. I didn’t need this shit mocking me. But then he turned round and said, ‘no. man, I dig Mott The Hoople! ‘Half Moon Bay.’ ‘Laugh At Me.’

“I can’t remember what I said to him that night…

“But the two artists I grew up with, Bob Dylan and the Stones (Mick Jagger) were both limited singers. But Jagger was the sexiest singer in the world, and Dylan would make your hair stand on the back of your head. Because his voice was so lousy. That’s the truth” he emphasized.

“I’ve got a lousy voice, and so have Randy Newman and Leonard Cohen. But it doesn’t really matter. I’m conscious of not being a good singer, but that’s just in your throat. I think we all get the message across.”

##

Patti Smith, has read and recorded a Kerouac poem “The Last Hotel” accompanied by music from Thurston Moore and Lenny Kaye. One of her favorite books is Kerouac’s Big Sur. Smith appeared in the Rolling Thunder Revue.

Smith, in a 2019 interview with Steven Gaydos of Variety, commented about the Beat poetry world.

“These people I got to know as my friends and mentors — William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso. They treated me really well when I was a girl working in a bookstore, writing poetry, and they became good friends as I got older and they were kind to my children. I never felt excluded. And in terms of rock and roll, I never genderized it — I just loved it, I was equally into Darlene Love and Jimi Hendrix.

“The Beats were all quite educated,” she said. “They all had gone through the Romantic poets and European literature and Rimbaud, and they had all this information — and the influence of jazz, with Kerouac writing while listening to jazz. They were all so evolved and intelligent their work was not just revolutionary — it had substance that we’re still plowing through. All these great teachers were his spiritual icons and they are all seeded in his work. And they all fought a lot of fights for us, censorship battles and [things like that]. They weren’t just workers and revolutionaries; they were teachers, and because many of them lived for a long time, we were privy to their teaching.”

In 2011, I interviewed Patti and asked about her improvisational skills and techniques in performing which I felt were akin to Kerouac’s recording endeavors.

“They are different responsibilities. Doing a record, one is doing something that hopefully will endure. And one is doing it in a very intimate situation. Just with one’s band members and a few technicians, and so it is very intimate, but one is mentally projecting toward the future and the people who’ll listen to it. Playing live you are right there with the people. I don’t think of live performance as enduring. It’s for the moment, somebody might bootleg it or tape it for themselves, but basically, I think of performance for the moment and it’s often more raucous, flawed, and you know, totally done for the people that are there.”

Twenty years ago, I interviewed Marianne Faithfull. In the early ’90s she was made a professor by Allen Ginsberg at the Naropa Poetry Institute in Colorado, where she taught lyric writing. Her certificate says: “Marianne Faithfull, Professor Of Poetics, Jack Kerouac School Of Disembodied Poets.”

That afternoon at the Chateau Marmont on Sunset Boulevard, she hailed the books of Kerouac, Burroughs and Ginsberg and grouped Dylan in her literary lineup. Marianne is glimpsed in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1965 UK tour portrait of Dylan, Dont Look Back.

“I find them very sexy all those guys. Wonderful. I adore Allen. The first time I went to Naropa, Allen was literally by my side like he is. There was a lot of criticism and ‘Who is the woman?’ ‘Why do you (Allen) think she can do this?’ And he didn’t say anything. ‘I just do.’ And then I came back again. We are very good friends. He also represents a lot of things for me that aren’t part of our friendship or our relationship. He is the greatest living American poet.

“I had never seen a rock person like Dylan or an American like him in 1965. Never. Never seen. Never in my wildest dreams could have imagined anyone like Bob in 1965. His brain, but I was frightened. I didn’t know they were probably more scared of me. He played me the album Bringing It All Back Home himself on his own. It was just amazing. And I worshipped him anyway. That was where I got very close to Allen, ‘cause Allen was the only sort of person I could recognize as being somewhat like me.”

##

On December 9th comes the return of Jack Kerouac on vinyl with Poetry for the Beat Generation and Blues and Haikus.

“Kerouac is the ultimate WAM, a white American male from the 20th century, 75 years down the road from his creative peak,” posed filmmaker Michael Hacker. “It’s impossible to read Kerouac now in any kind of quiet, in the stillness that reading demands, too much noise about Elon and Ye and so many other important things and nothing that sounds even remotely like silence anymore. I’d no more suggest to a person today who’s never read Kerouac to read him now than I’d suggest trying to find a decent hamburger in Los Angeles. What would be the point?

“But I would suggest listening to Kerouac, because in that space (with earbuds, natch) you can drown out the rest of the world and hear what he was trying to say and listen to his broken heart and see with him through his poetry what he was looking at. And that’s worthwhile. If you want to feel what San Francisco was like once upon a time, listen to October In The Railroad Earth. And the Haikus are so wonderful and moving and funny, Ginsberg said Jack was the only American who knew how to write Haiku. My favorite: ‘Useless! Useless!

Heavy rain driving into the sea.’”

“For us rock ‘n’ roll kids who came of age in the ’70s and ’80s, Kerouac was the portal into literature because he felt like rock and roll,” observed author and novelist, Daniel Weizmann.

“His kamikaze crop duster prose, his refusal to play the structure game, his ability to capture tenderness in the middle of chaos, his willingness to be openly enthused, to be jazzed – all of it brought him just a little closer to a spieling boss jock than some arch grey belles lettres schmuck. And despite incredible flights into the ethereal, Kerouac was trustworthy – he kept it real. He was a portal for us, just like he was a portal for the whole culture that led to us.

“And maybe it’s no accident that his masterpiece is about driving westward because Kerouac is also, in some funny way, a California writer, an embracer of the blazing sunlight, a seeker of the untamed. Whether walking the streets of L.A. or S.F. or sleeping in the wild fields, he is never a tourist.

“We claimed him for our own – a California rock ‘n’ roll hero — which is amazing when you realize what he also was – a poor French-Canadian kid from Massachusetts who couldn’t even speak English before the age of six, a printer’s son, a halfback who blew out his leg freshman season, a dishonorable discharge from the US Navy. But he made the journey, he beat down the path, and he was ours.”

“Jack Kerouac, for me, belongs with J. D. Salinger, Thomas Wolfe, and E. E. Cummings in the category of writers one must read before turning 20,” instructs poet/deejay and retired English and Literature Professor at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Dr. James Cushing.

Dr. James Cushing, 2010. (Photo by Henry Diltz / Courtesy of Gary Strobl, the Diltz Library)

“I read Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums at 19 and was utterly captivated by the narrator’s devil-may-care way of living and seeing and feeling, his free-flowing writing style, and, most of all, his sense of the freedom to be found on the road. I reread it (along with On the Road and Mexico City Blues) in my 50s and found myself feeling little or no sympathy for this sexist, egocentric jerk of a narrator, for whom the great end goal of the mythic road trip was to be home to spend Christmas with his mother. Christmas with his mother! For fuck’s sake!

“Add to that his blotto, hate-spewing appearance on William Buckley’s Firing Line and his support of the Vietnam War, and you have a larger picture: Kerouac as a 1950s bad-boy who work passed its sell-by date long ago.” Beat literature as it pertains to Romanticism: It’s time to ditch Kerouac in favor of Bob Kauffman, Diane Di Prima, Joanne Kyger, Gary Snyder, and don’t forget Richard Farina…”

“For those of us who entertain a terminally whimsical view of the human condition,” summarizes musician and author, Kenneth Kubernik, “‘the road’ is a mighty seductive metaphor. Infinite in all directions, literally and metaphysically, it’s an irresistible portal through which countless storytellers have journeyed, some with courage, some with reckless abandon, some content to ride shotgun – taking the wheel being too much responsibility.

“Homer took the bait; what was The Odyssey if not a mythically misguided road trip. Quixote and Panza’s canter through Andalusia in search of the impossible – another noble, if muddle-headed pursuit.

“America is no stranger to the beguiling indignities of heading out on lonesome highways, pedal down, no direction home, cat nip for romantics who struggle with the real thing.

“We read, enraptured, ‘watching the long, long skies over New Jersey, and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast and all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it…’ It’s bred in our bones, Manifest Destiny, Turner’s frontier thesis, the privilege of putting distance between yourself and your history. Lewis and Clark; Huck and Jim; Crosby and Hope (why not); Hunter Thompson and an assortment of Schedule 1 drugs. Springsteen would still be out there lost in his own tormented arcadia if Landau didn’t tether him to service more quotidian pursuits.

“My touchstone is that imperishable moment in Animal House when our heroes survey the wreckage around them and then, with clarion resolve rally the troops for – all together – a ‘Road Trip!’ I nearly rushed the screen to heed their call to action.

“Kerouac is, of course, the north star around which so much of this gravitational yearning takes place. He wrote the user’s manual for a generation (and a little beyond) eager to transform its’ post-war triumphalism into a debauched celebration of self-discovery and self-deception. His prose often crackled with the pop of a Philly Joe Jones rim shot; Ginsburg called it ‘bop prosody.’ Jack was crazy mad for Charlie Parker and the rattle and hum of 52nd Street; I hear him as more closely attuned to the tragic beauty of Art Pepper, whose playing caught the orphaned sound of an artist at the edge.

“Decades removed from its deeply-rooted ’50s setting, much of the writing has lost its narcotic kick. Like many a compelling if self-absorbed saxophone solos, the words tumble forth like a run-on sentence, that initial rush tempered by overstaying its welcome. The Beat movement itself now appears distant and, frankly diminished, even though their books, their posturing, their insouciant middle-finger to ‘I Like Ike’ conformity, remains consoling, even valiant to those who still consider the life of the mind valuable.

“In today’s heedless rush to celebrate the dazzling surfaces of our digital age – delighting the eye, dead to the touch – the idea of the road has retreated to a desolate backwater, at best a virtual memory as the Sal’s and Dean’s of today grind away in the Metaverse, jazzed by the clickity sound of Python swallowing them whole.”

“Alas, he never rocked my boat…I tried,” admitted wordsmith, record producer and author, Andrew Loog Oldham, “but ended up putting him in the same bin as Francoise Sagan …”

© Harvey Kubernik 2022

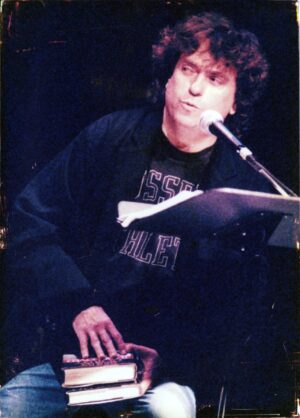

Harvey Kubernik. MET Theater reading, 1996. (Photo: Heather Harris)

Harvey Kubernik’s interview with Allen was published in Conversations With Allen Ginsberg, edited by David Stephen Calonne for the University Press of Mississippi in their 2019 Literary Conversations Series. Harvey is a contributor to Beat Scene magazine, and head of editorial for Record Collector News.

In 2020 The National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. exhibited a Harvey Kubernik essay on the landmark album The Band, which celebrated a 50th anniversary in 2019. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz.

Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972. For November 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

This century Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley’s The ’68 Comeback Special, the Ramones’ End of the Century, and Live at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, Big Brother & the Holding Company. Kubernik is the Project Coordinator of The Jack Kerouac Collection, a box set of recordings.

In November 2006, Harvey was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by the Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California. During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the two-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood.

Marshall Chess on the Legacy of Chess Records

By Harvey Kubernik

Veteran music business legend Marshall Chess is the son of Leonard and nephew of Phil Chess, the dynamic duo who founded the monumental Chicago-based blues label.

After departing from Chess Records in 1969, Marshall formed and served as President of Rolling Stone Records for seven years. He helped create the Rolling Stones’ famous tongue and lip logo and was involved as Executive Producer on seven Rolling Stone #1 albums during the 1970s.

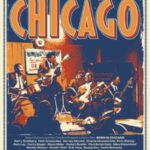

Marshall Chess is prominently featured and interviewed in the new Born In Chicago blues documentary that will screen on November 21st in downtown Los Angeles at the Grammy Museum.

Directed by Bob Sarles and John Anderson, and narrated by Dan Aykroyd, Born In Chicago is a soulful documentary film that chronicles a uniquely musical passing of the torch. It’s the story of first generation blues performers who had made their way to Chicago from the Mississippi Delta and their ardent and unexpected followers—middle class kids who followed the evocative music to smoky clubs deep in Chicago’s ghettos. Passed down from musician to musician, the Chicago blues transcended the color lines of the 1960s as young, white Chicago music apprenticed themselves to legends such as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf.

“The Chess brothers and their record labels were instrumental in popularizing the blues music of Chicago’s South Side,” emailed Born In Chicago co-director and co-producer Bob Sarles in summer 2022. Marshall Chess has kept that flame burning to the present day. His story about the Rolling Stones’ visit to the Chess Records studio is a highly entertaining part of our documentary.”

Marshall Chess was born in Chicago, Illinois on March 13, 1942, and was raised during the heyday of the independent record business. Leonard Chess had a piece of a record company named Aristocrat Records in 1947, and later in 1950 he brought his brother Phil into the fold and the brothers assumed sole ownership of the company and renamed it Chess Records. They also operated a club on the South side of Chicago, the Macomba Lounge.

Marshall “started” in the family business at age seven accompanying his father Leonard on radio station visits. For sixteen years Marshall worked with his dad and his uncle Phil, doing everything from pressing records, applying shrink wrap and loading trucks to producing over 100 Chess Records projects, eventually heading up the label as President after the GRT acquisition in 1969.

Otis Rush performs with Little Bobby at Pepper’s Lounge in Chicago, IL – December 17, 1963 (Photo by: Ray Flerlage/Cache Agency)

Over years the monumental Chess catalog has had various homes, including a 1975 sale to All Platinum Records, and eventually a couple of decades ago the Chess master tapes were purchased by MCA Records, now Universal Music Enterprises.

Chess Records showcased blues, rock ‘n’ roll, R&B, soul, jazz and comedy: Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Little Walter, Buddy Guy, Jimmy Rogers, Sonny Boy Williamson II and Little Milton. Maurice White and Charles Stepney both learned their craft at the label. [Chicago-based label International Anthem in September 2022 has just issued “Step on Step,” a compilation of Stepney demos and experimental music.] The label issued seminal efforts by Etta James, the Dells, Billy Stewart, and Fontella Bass. The Miracles, Four Tops, Bobby Charles and Dale Hawkins cut singles for Chess.

In addition, there was a jazz division with Gene Ammons, Ahmad Jamal and the Ramsey Lewis Trio. Argo, the jazz arm of Chess released material by Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers, James Moody, Clark Terry, Zoot Sims, Kenny Burrell, the Art Farmer-Benny Golson Jazztet (with the debut recording of pianist McCoy Tyner), Ray Bryant, Roland Kirk, Oliver Nelson, Jack McDuff, Illinois Jacquet and John Klemmer.

In the late 1960s Marshall created his own record label Cadet Concept, a division of Chess Records. He created and produced the Rotary Connection, which became the springboard for vocalist Minnie Riperton’s career. He signed John Klemmer and created a new format which was heralded as the first jazz fusion album, Blowin’ Gold. Marshall also produced the blues albums Electric Mud and After the Rain. The Chess comedy division offered long players by Moms Mabley, George Kirby, Pigmeat Markham and Slappy White.

Marshall has produced three films. The Legend Of Bo Diddley, Ladies and Gentlemen, The Rolling Stones, and the rarely glimpsed 1972 Rolling Stones’ Robert Frank-directed tour documentary Cocksucker Blues. Chess is also a revealing interview subject in Robert Greenfield’s 2006 captivating book Exile On Main Street: A Season In Hell With The Rolling Stones.

In 2004, Marshall was featured in a movie project collaboration titled Godfathers and Son’s directed by Marc Levin, for the PBS-TV series The Blues, produced by Martin Scorsese. Chess produced a hip-hop version of the classic Chess track “Mannish Boy” with rappers Chuck D and Common recording with members of the original Muddy Waters’ Electric Mud band.

In 2008, Marshall concluded a DJ stint hosting a weekly blues music program on Sirius Satellite Radio. His Chess Records Hour debuted in November 2006 and aired for 81 shows.

During 2009, I interviewed Marshall Chess in West Hollywood, California at the Sunset Marquis Hotel, and in 2010 I spoke with him by telephone from his office in New York City. Chess spent a few hours with me discussing Chess Records, the label’s legacy, his personal relationship with the company’s artists, and working with the Rolling Stones.

Born In Chicago documentary trailer:

https://player.vimeo.com/video/579679761?h=77163e65b2

Can you explain how Chess Records worked? Can you even compare or contrast Leonard and Phil Chess? How could your uncle and father know so much about music, the blues, and bringing it to the world? They were Polish immigrants.

Because they were very bright people. They worked in black businesses. My dad had a liquor store. I sat around my uncle and asked, ‘everyone always asks me about music, and how did Chess get into music.’ And, my uncle’s vision is this. That in Poland, in the small Jewish ghetto town, there was no music. Then some guy got a windup victrola. And the whole fuckin’ village would stand underneath this guy’s window when he played it. That was the first recorded music they heard. They come to America.

My grandfather, who was here seven years prior in Chicago brings them. He had a scrap metal yard. Across the street from it, on the west side of Chicago, was a black gospel church. My uncle said that my dad and him were kids, and after work they would hear the bass drum and gospel singing with a piano, they would be fascinated. They would stand there and get punished for being late, ‘cause they were listening to the black music. That’s where it began to me.

For some reason it affected them. And then, when my uncle went into the army, my dad, I think because he was an immigrant got him near Maxwell Street, the black neighborhood. No prejudice. That’s just it. No blacks in Poland. You don’t get raised being prejudiced in Europe. You hate Nazis, but no blacks to hate. So, they had no problem, and they saw that there was this giant influx of blacks in Chicago, and they had money, and they were working. And my dad started with a liquor store after he worked in a shoe shop. Berger’s shoes. Then the liquor store, where he had a jukebox, and he was there 15-18 hours a day hearing blues. I watched the jukeboxes being serviced. They used to be controlled by gangsters of Chicago. They’d come and pick ‘em up from us. The Italian gangsters.

Can you offer some reflections about the Chess studio?

We had fabulous engineers. Ron Malo and Malcolm Chism. They were the two best engineers. Ron came from Detroit. He had worked on Motown studios and he was a big part. Before Ron, we had these two Weiner brothers, who actually built the studio. It was a basic classic studio design, with the echo chamber in the basement, very small control room.

One of the secrets of the Chess studio was not the studio but our mastering. We had a little mastering room with a lathe. Eventually we had a Neumann lathe. The first one was an American one. We did our own mastering and had these Electrovoice speakers on the wall.

The great part about that room that when it sounded right in that mastering room it would pop off the radio. That’s what it was all about. And the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, later Fleetwood Mac had to make visits there.

The Chess sonic delights are amazing.

The best explanation is, this may sound way out. It contains magic. The most apparent magic that we can see or experience is music. Let’s face it. Music changes the way you feel. That’s magical. Chess Records for some reason was a magnet for amazing artistry and all these magicians came to Chess. And we were able to capture it. And it’s something that can be experienced through audio. The music has stood up without a cinematic aspect like video. And the method of recording.

As I grew older, and was a person of the hippie generation, and discovered things like meditation, psychedelic drugs, Buddhism. I realized what was happening in the early Chess studio was like a high Buddhist monk meditation manager. Because when you recorded in mono and two-track with 5 or 6 players and a singer there wasn’t any correction possible. One of the main jobs as a producer was like a meditation manager master. He had to get the band locked together to go down. I remember when they were teaching me to produce, they always would say, “when the motherfucker fucks up you got to embarrass him and tell him to play that shit right. Over and over.”

Vee-Jay Records was across the street from Chess in Chicago.

Ewart Abner was a good friend of mine. The Vee-Jay stuff came later. It was more on the edge of ‘60s. That led into the Impressions, Curtis Mayfield all that part of Chicago. The thing that this early music has is that it just has some fuckin’ kind of magic in it. I think maybe it’s the direct to two-rack recording of the period. I don’t know what it is. Some kind of alchemy. A real esoteric alchemy. That’s what drew the Stones to record in our studio. There’s some alchemy in those early records that even carries over when you sample them. Jerry Butler and Dee Clark. Brilliant singers. Amazing. They all come from black church. Etta. Every one of them. This is the shit, man. All these motherfuckers learned from church, or the fuckin’ cotton fields in Mississippi.

I love Chess Records. Because it was the greatest, happiest place in the world. You would love going there. You laughed all fuckin’ day. The artists hung out there, no, not all the artists, but what we would call the family artists. Sonny Boy, Muddy Waters, Dells, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley.

And Billy Stewart!

Billy Stewart shot the doorknob off at the studio if they didn’t let him in quick enough. What was Billy Stewart mad about? ‘I brought some fuckin’ pepper stuffed crabs from Baltimore. You gotta taste them before they get ruined!’ We were into eatin’ and laughing. Maurice White is the drummer on Billy’s ‘Summertime.’ I saw genius in him. He was the first black guy that ever had a Volkswagen. He was like the first of the switch from the Cadillac to the cool.

I’m proud and I’m thrilled, and helped historically continue the legacy of the Chess Records label. I’m not a classic blues fan, a blues collector, I am not into the anal aspect of what guitar strings Muddy used, or what harmonica did Little Walter play.

I only wanted to be around my family, and my father, who was a workaholic. It was a family business. They were immigrants and embraced that. For age 7 to age 12 or 13, my dad took me on the road, not because I wanted to be in the record business but because I wanted to be with my father. So, I got it really by osmosis, ya know. And that was my real reason for hanging out there.

In Hollywood at Fairfax High School, the Father and Sons album released with Muddy, Otis Spann, Sam Lay, Buddy Miles Paul Butterfield, Michael Bloomfield, and Donald “Duck” Dunn was the big hit in the school hallway with collectors and stoners. It’s been reissued by Universal. The version of “Long Distance Call” is totally amazing!

Man, and live, you couldn’t see it, Muddy did this dance on ‘Got My Mojo Working’ that was unreal! Like Nureyev. He put down his guitar and did a pirouette. The place went wild! You can hear it on the record. You can hear the crowd when that happens.

Muddy Waters being interviewed by Mike Bloomfield, Chicago, IL; circa early 1960’s. (Photo by Ray Flerlage/Cache Agency)

What sort of images flash in your head when you play the music of Chess Records?

I see them. My dad and uncle. Man, that’s what goes through my head. Sonny Boy Williamson and Muddy Waters went to my Bar Mitzvah. A lot of black people were there which was a very unusual event back then in 1955.

The Chess recording artists were always writing about women problems and sex. That’s all I ever heard from them when I was a kid. I saw some of these records being recorded. I sold them originally. I helped their initial exposure. On the SiriusXM radio program I brought more exposure.

But being around the blues, and all these records being made, and knowing the artists, I don’t know, man, it just, ya know, got into me. It just became part of me. It’s part of my life. I’ve never even considered it work. I appear and promote Chess and the blues in films and TV documentaries. I do as much as I can because I get a buzz out of it. I’m just amazed, man, that this music that we made in Chicago has become so historical

In the Chess stable as far as songwriters like, who, was your main man?

Chuck Berry was the best. He had a spiral notebook, a fuckin’ school spiral book. I saw all those lyrics written out. Like poetry, man.

The earliest I saw Chuck Berry was 1969. He was having pickup bands even then.

A pick up band… In the mid to late 1950s he was just brilliant. Johnnie Johnson on piano. I don’t remember much. The first session I remember in detail when he came out of jail was ‘Nadine.’ I was his road manager for six gigs. I brought him his clothes when he came right from the prison. My dad gave me $100.00 to take him down next to the Chicago Theater on State Street to buy him a new outfit. And then we went on tour. The first gig we did was in Flint, Michigan, with the Motown rhythm section backing him.

I never got to see that…

Chuck was great. But I always felt he was too greedy. He ruined the alchemy because those pickup bands, as good as they knew it, weren’t locked, like if it would have been his own band. That’s why in Keith’s movie he had all those problems with Chuck. He wouldn’t lock. And he lost it. He needed my father there. I don’t know if I could even deal with it. My dad was the one. As for guitar playing, he invented that whole thing, ya know. And he sang and wrote the words, too.

Howlin’ Wolf poses backstage with his guitarist Hubert Sumlin, in England; 1964. (Photo by: Brian Smith/Cache Agency)

Run down some of the other Chess artists. Howlin’ Wolf. I loved it when he was on Jack Good’s Shindig! television show in 1965 when the Rolling Stones were booked.

Howlin’ Wolf…On stage very commanding, but off stage a very gentle, soft man. I remember him telling me he was learning how to read music. Did you know that? He went to school to learn how to read music so he could learn how to play the guitar. He wanted to learn notes. One time my dad had me bring him a thousand dollars to his house, and he opened like those tool boxes that you lift off the tray at the top. And it’s stacked full of money. “What do you need this money for?” “I gotta go buy some special dogs to go huntin’ on my farm.” (laughs). He was a gentle man but ferocious. Big. He used to drink a lot. He was pretty much high a lot when he performed.

Muddy Waters – Chicago, 1964. (Photo by: Ray Flerlage/Cache Agency)

Muddy was the showman and a towering regal figure.

Muddy liked to drink. Muddy on stage and in the studio was the best. He was organized. He was a fuckin’ leader. I always say this. People say ‘what do you mean?’ He was a fuckin’ leader. Muddy was the reincarnation of a tribal chief, of a President, of a King. Such a powerful presence. I just loved him. And he treated me so good. He used to call me his white grandson. His wife Geneva used to send me fried chicken wrapped in foil. Muddy once wrote a poem to a girl for me that I gave when I was in high school. I always say this and people laugh but most of what I discussed with these guys was about sex. That was the main thing on their mind.

In the fifties and very early sixties there were clubs, during that early blues heyday of Muddy, and Wolf, they were places where people went primarily on weekends to find women. And women to find men and to party. And the music was very much party music. It was like a psychological influence on the people in these little clubs. And it was what these guys wanted to do. Drinkin’ and make love.

It then began to die out as R&B and Motown happened. It’s a period when I was in a few of those clubs that were hot and steamy and smelly and funky and the music was loud. Those were the clubs where Muddy Waters put the coke bottle in his pants and Wolf got down on his knees, howling, drinking whisky out of a bottle. Those were a whole different audience then when the white blues market discovered it.

Look at their lyrics. With the TV programs recently on Muddy. The American Masters documentary, it’s all very gratifying. We always knew it. Gratification is the best word. Not for all of them. Muddy, Wolf, Chuck Berry. These are like Beethoven and Bach. They should be right up there.

Buddy Guy – Chicago, 1960s (Photo by: Ray Flerlage/Cache Agency)

Buddy Guy?

Buddy Guy brought me a real mojo from Mississippi that I used to wear when I was in high school that I used to wear when I was trying to get girls. This little pink bag I pinned to my under shirt.

Bo Diddley?

I have always considered Bo Diddley to be one of the most creative, innovative and original of all the Chess artists. From his custom guitars that he built himself to his constant searching for new sounds. He has influenced many recording artists with his originality. He was not afraid to take chances with his music. Chess Records was the perfect place to be as we to were not afraid to experiment with new sounds and ideas. During the 50’s both Bo and Chess were always ready to push the envelope. Brilliant artist. A true original. Great artist. But he’s a trip. The thing I remember about Bo, and here’s my memory. I remember Bo with this long airport limousine broken down in front of 2120 S Michigan Avenue on his back repairing it himself in the street jacked up changing the rear end or something. On the curb. You know what I told Bo Diddley? “The reason you’ve never had another hit is because your creativity is tied up in bitterness. I said let that shit go and you can have a hit tomorrow. You’re a fuckin’ genius.”

Willie Dixon?

Willie Dixon. Songwriter, producer, bass player. He’d get the bands together. I think he was a great songwriter and a great –promoter and a real hustler and he was a great guy. He was very important to the success of Chess and I will not take that away from him. He wasn’t Chess at all. But he was an important part of Chess Records. Very important part of that blues era.

Etta James?

The Queen of Soul. They were calling her that before Aretha (Franklin). She’s just great. She started singing in church. She’s a real L.A. girl. A street girl. Johnny Otis broke her out on Modern, and then she had that hit “Roll with Me, Henry” that was later re-titled “Dance with Me, Henry.”

In 1960 she came to Chess and our Argo label, and then another hit in ’61 with “At Last.” In 1967 came “Tell Mama.” Both great records. They blew our minds. We loved good shit. We knew when it was good. (Laughs). We had black radio in our pocket. We were strong. Not only that, we had a radio station WVON. (Voice Of The Negro) which was part of it. E. Rodney Jones was our program director.

Little Walter? People are still talking about him.

He’s the truest genius of all the Chess artists. Because he invented and perfected a new way to play the harmonica, and did it with tremendous creativity and talent. Very much like Hendrix with guitar. They’re exactly alike. Miles Davis considered Walter a genius. Hendrix considered Walter a genius. I liked him as a person but he was always drunk. I never knew him when he wasn’t fucked up. Smelling of liquor. But, yeah, I liked him. There was something ‘sloppy drunk’ about him that I liked. But he had a mean side to him, too. I saw him and my dad go at it with anger numerous times when he was drunk. He’d be a mean drunk. But we loved him. And my dad and my family loved him. We buried him.

You issued Electric Mud by Muddy Waters and have been defending it from the day of retail release.

Here’s the true Electric Mud story. I produced it. I recorded it and promoted it. At that time, I was very aware and very on top of alternative FM radio. I drove across the United States, visiting FM DJ’s like Tom Donahue and Bobby Mitchell in San Francisco. I’d meet all the DJ’s at radio stations in Los Angeles like KMET-FM and KPPC-FM and meet all these people. And these guys would be smoking joints on the air and they’d take an album right from your arm and play it immediately five times on the air!

FM “Underground” radio gave airplay to blues recordings during 1967-1970

Those were the great days. I was part of the generation. When everyone took LSD to watch the Grateful Dead, I did. I’ve been at the Fillmore West sitting on the floor. What happened to me was that I was part of that sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll generation. And it blew my mind.

Bill Graham was the greatest for that for the blues artists of that era. B.B. King on the bills. FM radio was a Godsend for the blues. The big commercial AM stations would not play the records at all except some black stations. And I decided to repackage Chess to that market that was getting stoned and going deep. It was a big boost when the English groups covered the music earlier. On records and at their shows. We loved it and something we thought could never happen.

Muddy Waters and B.B. King really dug white people doin’ their stuff. Sonny Boy was very much into white people doin’ his stuff. So was Howlin’ Wolf. I remember (Eric) Clapton gave him a fishing rod. Wolf was a real sportsman. He had fuckin’ huntin’ dogs that were a thousand dollars each. It blew our mind, of course it was a fantastic thing. We loved it. And we never thought that could happen. It was a total fantasy. But we first noticed it with the Muddy At Newport album came out. See, albums were not selling to black people. They didn’t have record players. I can remember we got all these orders from Boston on the Muddy album and we knew it was white people buying it. College kids. The first things we noticed as the album market developed.

In 1984, you became a partner in the established blues rock publishing company, the Arc Music Group, which he began actively heading in 1992. You and the Arc Music team placed Chess Records-birthed recordings and music copyrights into major motion pictures, television shows, and TV commercials. You just oversaw the sale of Arc Music to Fuji Entertainment America.

I’m in shock and still haven’t realized it. It was time. We’ve had people chasing us since 2001. We’ve just been waiting for the right buyer. It was the right price with the right respect for the catalogue.

Chess Records fans Charlie Watts and Paul Body at the Motown Museum, 2015.

© Harvey Kubernik 2010, 2022

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows published in 2014 and Neil Young Heart of Gold during 2015. Kubernik also authored 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, David Leaf, Dick Clark, Curtis Hanson and Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

In 2020, Harvey served as a consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood that debuted on the M-G-M/EPIX cable television channel. During December 2021, Kubernik was an on-screen interview subject and received a consultant credit for the rock & roll revival music documentary currently in production about the story of the Toronto Canada 1969 festival featuring the fabled debut of the John Lennon and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band and an appearance by the Doors. Klaus Voorman, Geddy Lee of Rush, Alice Cooper, Shep Gordon, Rodney Bingenheimer, John Brower, and Robby Krieger of the Doors were filmed by director Ron Chapman).