-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

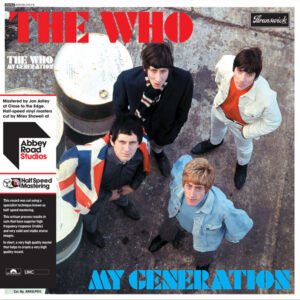

The Who: Half Speed Mastered Albums, Shel Talmy, Pete and Roger on the Monterey International Pop Festival and more

By Harvey Kubernik

Keith Moon, the drummer of the Who and I in 1975 did an interview for the now defunct Melody Maker at the Laurel Canyon home of his manager, Skip Taylor, the record producer of Canned Heat since 1967. That year I witnessed the Who’s Southern California live debut at the Hollywood Bowl.

In our ’75 conversation, Moon and I discussed the Who.

“Everybody labors under the misconception that Pete Townshend is the leader of the band. There is no leader. It’s the Who. We’re a group. Each individual is one fourth of the whole. There’s a lot of talent in our group.

“Tommy never stopped growing. When Pete was writing it, he got to a point where he was saying, ‘Where do I go from here?’ We were sitting in a boozer in London, which is most unlike us, throwing ideas around. And I said, ‘Well, what about a holiday camp?’ So, it was ‘Tommy’s Holiday Camp’. This is how the Who works. Everybody contributes, everybody is part of what we are involved in. The involvement is total, with no one person in control.”

Just issued in May from UMe is the first in a series of half speed mastered studio albums from the Who; My Generation and A Quick One. These limited-edition black vinyl versions have been mastered by long-time Who engineer Jon Astley and cut for vinyl by Miles Showell at Abbey Road Studios with a half-speed mastering technique which produces a superior vinyl cut and are packaged in original sleeves with obi strips and certificates of authenticity.

July will see the release of two more half speed mastered Who albums, The Who Sell Out and Tommy.

Regarded as one of the most important albums of all time, Tommy is a rock opera about a deaf dumb and blind boy, which, when released in 1969, reached No 2 in the UK charts and No 7 in the US. The album contains songs such as “Pinball Wizard,” “The Acid Queen” and “I’m Free” and is packaged in the original sleeve artwork.

Released in 1967, The Who Sell Out was the third album released by the band and is revered for being one of the first concept albums, celebrating the short-lived pirate radio stations of the late ‘60s with its groundbreaking use of fake adverts and jingles between songs. Highlights include “I Can See for Miles,” “Armenia City in the Sky” and “Tattoo,” and as with Tommy, it’s also been mastered by Jon Astley.

First released in 1965, My Generation, produced by Shel Talmy, was the Who’s initial album, it peaked at #5 and unleashed the Who on the world. It has been described as one of the greatest albums of all time by Rolling Stone, MOJO, NME and was selected to be the US Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry as “culturally significant” to be preserved and archived for all time.

The band’s follow-up album A Quick One was released in late 1966, it contains more experimental compositions including the nine-minute title track which act as precursors to what was to follow in later years as well as classic Who tunes as “So Sad About Us” and “Boris The Spider.”

“Shel Talmy is the brilliant producer that developed the hard rock part of the British Invasion, which was the birth of Hard Rock period,” emailed Steven Van Zandt in a May 2022 correspondence. “And he did it with half instinctive genius and half outrageous chutzpah! If he’d done nothing but the first five Kinks albums he’d belong in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Then again, if he did nothing but the first Who album he’d belong in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame! In other words, HE BELONGS IN THE FUCKING ROCK AND ROLL HALL OF FAME!” Van Zandt’s autobiography, Unrequited Infatuations was published in 2021.

I’ve felt the technical and sonic contributions that producer Shel Talmy installed on the first Who mono LP have rarely been acknowledged and also marginalized in today’s revisionist history written about the legendary band’s 1965 studio endeavors. Talmy discovered the Who after seeing their live act and inked them to his production company. He secured the band a contract in America with Decca Records and their subsidiary label Brunswick in the UK.

Music journalist and SiriusXM deejay Dave Marsh in his book on the Who, Before I Get Old, mentioned that the records Shel made with the Who “are technically among the best that the band ever did, and they have a distinct, original sound.”

Talmy in 1962 was one of the UK’s first independent record producers. Known for his work on the earliest discs by the Who and Kinks, he produced marvelous recordings by Pentangle, Chad & Jeremy, the Fortunes, the Easybeats, Amen Korner, the Creation, and the Paul Jones-fronted Manfred Mann. In 1965 he produced a singer named David Jones, soon to be called David Bowie. Talmy also helmed groundbreaking 1964-1968 album productions by the Kinks. Ace Records in 2017 released a terrific album of Talmy’s 1963-1967 studio activities, Making Time: A Shel Talmy Production of various artists.

Shel is currently working on his autobiography.

In 2017 I conducted an interview with engineer/producer/arranger/author Talmy, born in Chicago, later a graduate of Los Angeles’ Fairfax High School, and college student at Los Angeles City College and UCLA. Talmy subsequently worked at ABC-TV on Prospect Avenue which became home to the landmark TV series, Shindig! An appearance of the Who was broadcast in 1965.

“I started as an engineer with Phil Yeend at Conway Studios in Los Angeles. Phil was English. I spent a lot of time trying to perfect the sounds we were getting at Conway,” explained Talmy. “We spent time isolating instruments, working on drum sounds, working on guitar sounds. In terms of days and hours, microphone placements we did were utilized eventually with the Who and Kinks.”

During his stint at Conway, Talmy was trained by Yeend on three-track recording equipment. Shel worked with artists and producers, including Gary Paxton, the Marketts, and R&B legends multi-instrumentalist/arranger Rene Hall and record producer Bumps Blackwell. Talmy immersed himself in production techniques taught by Yeend: Separation and recording levels, employing baffles built with carpet on the studio floor, vocals and instrumentals cut in an isolation booth setting.

“I brought with me from Conway a way to using the equipment of making everything louder apparently louder than it actually was. I did that with bringing up a guitar through channel one, which was right at the beginning of distortion and the other one which was normal. So, I used to bring up the distorted one underneath the good one and the entire level went up. And I always tried to do everything I could without distorting. So, I was always near the red line of the meter. I brought that with me. I liked hearing records that I think it actually expands the vocal audio range of what you’re hearing. As far as echo, Conway had a damn good echo chamber that Phil worked on and it was in a little closet. I like echo where it applies and I don’t like echo where it doesn’t apply. There’s a lot of stuff I think that sounds a hell of a lot better dry then it does with echo.”

“Record producer Nik Venet gave me his demos and acetates when I first came to England in 1962 and that is what I used to talk my way into a gig at Decca with Dick Rowe in A&R. I played him ‘Surfin’ Safari’ by the Beach Boys and ‘Music in the Air’ by Lou Rawls. He was very impressed. What I learned from Nik, bless his heart, was how to handle artists. He allowed me to come to Capitol studios while he was doing stuff. I went to one of his Lou Rawls’ sessions. Lou and Sam Cooke were fuckin’ brilliant. I would hear how he would talk to artists and the engineers. And I have done that forever,” he underlined.

“I returned the favor and I wrote to Nik and said ‘there’s a band called the Beatles you really got to take a listen too. I think they are gonna be enormous.’ Never heard another word. Thirty years later I ran into Nik at a studio and he told me when he got my letter he ran into Alan Livingston’s office, the head of the Capitol label in America and badgered them into signing the Beatles. Nik signed the Beach Boys in 1962.”

Talmy introduced influential West Coast developed bio-regional aspects of sound recording into the English studios like IBC, Pye and Olympic.

“The UK technical people didn’t think I was weird. They thought I was different because I was pretty much the first American producer there. The first place I went to was IBC on Phil’s recommendation. That’s where Phil worked. And, they were way ahead of everybody else. In terms of gear, they had young engineers who were willing to experiment. Glynn Johns. And then Olympic. Initially it made my life easier. Glyn Johns and Eddie Kramer, who I used twice. Gus Dudgeon was my assistant at Olympic with Keith Grant.

“I’ve always felt the song was 75 per cent of the record,” Shel reinforced. “But I still subscribe to the fact that if you’re gonna hear a great song you’re gonna pretty much know it in the first eight bars. And then it continues to develop, three to four minutes is about the right amount of time for it.”

I asked Shel if he could compare Pete Townshend and Ray Davies as songwriters.

“Contrasting Pete and Ray. The easy way in broad strokes… Is that Ray was the major social commentator of what was going on in England at the time. Pete was much more into early blues and what he could so with his guitar and loved sound.

“Of course, I encouraged all the power chords and all that kind of stuff and that’s what attracted me when I first heard them. I thought they were the first rock ‘n’ roll band I heard since I came to England. When I first arrived, I thought everything was incredibly polite. Pete and Ray, the only thing they really have in common is that both of them are really brilliant songwriters. I think it’s fair to say that Ray could not write a song that the Who would do and Pete could not write a song that the Kinks could do. As a producer I knew they had global appeal. Absolutely.”

We also discussed pianist Nicky Hopkins, heard on My Generation. “Nicky Hopkins… With the Who and the Kinks. I found him real early. Nicky was one of my favorite people. A really nice guy. Easy to work with. A heavy duty talented musician. I had him playing live with all these people, by the way. I didn’t bring him in for overdubs. I don’t know how to describe him. When you hear something that’s un definable but you know it is brilliant. That’s what I saw with Nicky Hopkins. All the bands loved him that I introduced him too.”

Talmy also commented on the Kinks’ Dave Davies. “I’ve been saying for years that Dave Davies is probably the most underrated guitarist in rock ‘n’ roll. A damn good guitarist. He’s also a very good songwriter. He’s not as good as Ray, but then again, very few people are. Ray was in a class by himself. As was Pete Townshend, Lennon and McCartney. Dave was one small step beneath that in terms of how good he was. But he wrote some damn good stuff.”

“I saw Shel [Talmy] recently in Los Angeles when I did a show at the Roxy Theatre,” Dave Davies emailed me last decade. “It was good to see him and he seemed great. I thought he really helped us in the beginning and he was good to have around in the early sessions. I always appreciated how he supported me and has praised my amp sound, guitar playing and solo on ‘You Really Got Me.’ He’s a good guy.”

Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend published their own memoirs (Pete’s Who I Am was released to much acclaim in 2012, and Roger’s autobiography, Thanks A Lot Mr. Kibblewhite; My Story, was embraced by critics in 2018). The two remaining Who members have released their first new album in 13 years, the acclaimed WHO in 2019 and are currently on the road in the USA with THE WHO HITS BACK tour.

The Monterey International Pop Festival celebrates a 55th anniversary in mid-June 2022. An event that helped introduce the Who to America. DA Pennebaker’s seminal documentary Monterey Pop followed which further propelled the band’s global status.

Johnny Rivers, Ravi Shankar, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Association, Beverley Martyn, Lou Rawls, Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Byrds, Canned Heat, the Mamas & the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, the Group with No Name, Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Mike Bloomfield Thing, Country Joe and the Fish, Hugh Masekela, the Steve Miller Blues Band, Moby Grape, the Blues Project, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Eric Burdon and the Animals, Otis Redding, Laura Nyro, and the Paupers performed during the three-day event.

During 2007 I interviewed Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey about that weekend of June ’67 that changed outdoor festival culture forever. Rolling Stones’ manager/record producer Andrew Loog Oldham suggested the Who for the booking to producers John Phillips and Lou Adler.

The Who onstage at Monterey, June 18, 1967. (Photo by Henry Diltz / Courtesy Gary Strobl)

“We were pretty scared,” emailed Townshend. “We’d done a package in New York City with Cream, and it seemed as though we’d missed a beat. We were still displaying Union Jacks and smashing guitars while Cream played proper music and had Afro haircuts and flowery outfits. Jimi had already hit in the UK. This was a divine opportunity. A side issue was that we played at the Fillmore on this trip, and that was probably more important to us, because Bill Graham insisted we play a longer set than we were used to. So we had to really begin to play proper music, like Cream I suppose. It was around this time we began to include songs like ‘Young Man Blues’ and ‘Summertime Blues.’

“It was exciting to go to San Francisco for the first time, but also quite strange. The music industry people were pretty whacked out by LSD already in a way that hadn’t happened in the UK. . .

“I remember Brian Jones, sweet as ever. Eric Burdon himself as solid as ever, at least face-to-face he was a good bloke. Jimi was out of his tree. Derek Taylor was frightened to come out of his little box from where he handed out passes. The beautiful people gazed at each other. Mama Cass was adorable. John Phillips was too. It was a nice vibe, as we used to say. But we were keen to stay true to our thesis, which was that this is a crock of shit and the war isn’t over yet—we meant World War II, not fucking Vietnam. So to say the least we were slightly out of step. The Who was a pretty tough band to be in. I took my girlfriend; we hung on to each other.”

When asked about his experiences at the Monterey gathering, Pete Townshend recalled his feelings about Jimi Hendrix: “We [the Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience] were both competitive. He felt like something of a newcomer, and standard-bearer for black blues, I think—that he may have felt had been plundered by the British sixties bands. But he and I debated about who should go on first. I felt he was a master, a genius. I was not prepared to follow him, not because I was afraid to follow him but because in my old-fashioned showbiz mind the best artists go on latest in the set. In the end we tossed for it, and Jimi lost. We went on first; he then announced that if we preceded him, and set the crowd alight with our destruction act, he too would set them alight. So the crowd got two mind-fucking sets.

“Others may remember it differently. I couldn’t see how the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, or Country Joe could be taken seriously. Their sound was so ragged, so raw. I was used to a slicker sound. Now I see better what they were doing, and just like the Who it was not just about music, it was about message and lifestyle and change. The three bands I mentioned all had manifestos that were not just about the music. It took me a while to understand that.”

“I didn’t see anyone at Monterey,” Roger Daltrey told me. “We were just ushered in and put under the stage a couple of hours before we went on. And then we were kind of escorted out after the set. They weren’t best with us because we broke the equipment up and they were very worried about their microphones and all that kind of stuff. [Laughs.] It was quite funny and we weren’t allowed or welcomed to stay. [Laughs.] We reminded them that this world was in a shit state, it wasn’t peace and love at all. [Laughs.]

“In August 1965 we played Richmond Jazz Festival with Solomon Burke—a tiny affair with a tent and a cricket pitch. . . There was a lot of camaraderie at Monterey with the bands, because we didn’t know what we were doing. Any of us. No one had written the rules.”

© Harvey Kubernik 2022

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows published in 2014 and Neil Young Heart of Gold during 2015. Kubernik also authored 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, David Leaf, Dick Clark, Curtis Hanson and Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

In 2020, Harvey served as a consultant on the two-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood that debuted on the M-G-M/EPIX cable television channel. During December 2021, Kubernik was an on-screen interview subject and received a consultant credit for the rock & roll revival music documentary currently in production about the story of the Toronto Canada 1969 festival featuring the fabled debut of the John Lennon and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band and an appearance by the Doors. Klaus Voorman, Geddy Lee of Rush, Alice Cooper, Shep Gordon, Rodney Bingenheimer, John Brower, and Robby Krieger of the Doors were filmed by director Ron Chapman.