-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

The Sounds of East LA and the Chicano Movement: Upcoming Grammy Museum In-Person Event

By Harvey Kubernik

On Wednesday, April 13, 2022 at 7:00 PM, the Grammy Museum in downtown Los Angeles will be presenting “The Sounds of East LA and the Chicano Movement” in conjunction with the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

Musicians Mark Guerrero and Little Willie G of Thee Midniters, UCLA’s Dr. Veronica Terriquez, and moderator Dr. Melissa Hidalgo will discuss the history of the Chicano Movement as it relates to the GRAMMY Museum’s Songs of Conscience, Sounds of Freedom exhibition.

For over a half a century I have collected, touted and supported the hidden bio-regional sonic achievements birthed from East Los Angeles and the Boyle Heights area in numerous publications and examined at length in my 2014 book, Turn Up The Radio: Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972 as well as interviewing musician, archivist/scholar Mark Guerrero, and lead singer of Thee Midniters, Little Willie G (Garcia).

The East Los Angeles and the Boyle Heights community, east of downtown LA, has given the musical world Top 40 hitmakers, Verve Records’ founder Norman Granz, Herb Alpert, Lou Adler, HB Barnum, Mike Stoller, musician/deejay Lionel “Chico” Sesma, author Gene Aguilera, along with actor and TV producer, Jack Webb, who was an active jazz collector.

During 2022 I’ve also been working on a music documentary, both Guerrero and Garcia were among the many subjects lensed for the cinematic endeavor.

Little Willie G: When I was ten years old, I went to the Strand Theater on Vernon and Main and watched the movie Blackboard Jungle. I heard Bill Haley & His Comets, and I was never the same.

I grew up in South Central. R & B is on the radio. Hunter Hancock is yelling about Gonzalez Park. He’s throwing these gigs in Watts at baseball diamonds like Wrigley Field. Tom Fears was a football player for the LA Rams, and he had Taco Tom’s on the corner of 41st and Central. We would walk by and talk to him. He would sign an autographed picture of himself, and then we’d sell it for a nickel.

I went to school on 34th and Central. St Patrick’s, a few steps from the Elks Ballroom on Jefferson and Central—this is where I first heard Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan rehearsing for a show they were going to be doing at the Lincoln Theater. We made the trip every day to Flash Records and Dolphin’s of Hollywood.

I was 16 or 17 on my first trip to El Monte Legion Stadium. You needed a permit from the school district to go to the place. That always used to blow my mind. Don Julian & the Meadowlarks with the Penguins were on the show, along with Tony Allen, who had “Night Owl.” He was actually my neighbor. Richard Berry, Don Julian & the Meadowlarks, Jesse Belvin, and Tony Allen used to rehearse at Tony’s grandmother’s house. I would hear them and shine their shoes. When Jesse died in 1960, they had his funeral at the Angelus Funeral Home on Jefferson. My first singing quartet I was in, we went over there and paid our respects to Jesse, who is overlooked in history.

In 1960, when I started going to high school, I met Raul, Benny, and Richard Ceballos, and they had a band. The drummer was Jerry Ainsworth, who was an Orthodox Russian Jew who lived in Boyle Heights. As a dig to his dad, we called the band the Gentiles, ’cause every Wednesday, when we would pick up Jerry for rehearsal, we could hear his dad yelling, “Jerry! Jerry! What’s the matter with you, hanging around with those unclean Gentiles!” Every Wednesday, the same spiel. What a way to get back at his dad, by seeing our names on posters all over East LA.

We were just a garage band. After a while, the name the Gentiles didn’t look as glamorous on posters as the Romancers and Richard & the Emeralds. So we felt we had to change our name and image and we kicked it around, and Hank Ballard & the Midnighters were one of our favorite groups.

We all were throwing names into the hat that day. “Thee” was Eddie Torres’s idea to set us apart, and thus started a wave of “Thee” bands all over the East Side. We talked a lot about who were our favorite bands, and Hank Ballard & the Midnighters was high on everyone’s list!

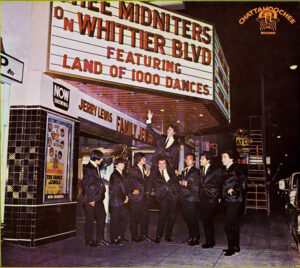

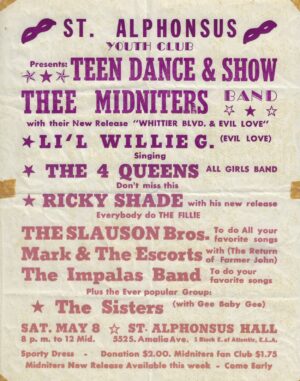

First we changed the spelling of Midnighters. It could have been our manager, or someone in the band who suggested “Thee” at the front. Perhaps Bobby Cochran, Eddie Cochran’s nephew, was one of our guitar players in that early band. [We said,] “Let’s be Thee Midniters!” In 1961, it was Benny & Thee Midniters, and we did a battle of the bands at St Alphonso’s Hall [at East LA College]. We employed “Thee” in front of our band name because we wanted to emphasize who we were.

The group recorded in Hollywood on Melrose Avenue, at Studio Masters with Bruce Morgan, who was a godsend. He had worked with the Beach Boys there and was just an incredible guy. “What do you guys want to sound like?” We told him, “We want to sound the way we sound live, when we are playing on a stage or in a backyard.” There’s an energy, vibe, and cohesion with a unity that comes across.

We recorded over 25 singles. It was right across the street from Paramount Pictures. Studio Masters was right next door to Lucy’s El Adobe Café. It was not unusual to go into Lucy’s El Adobe and see Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner come in wearing full makeup during their lunch break from filming the Star Trek television series.

After “Land of a Thousand Dances,” the British Invasion happened in 1964 and 1965. At rehearsal, one of our warm-up songs was “2120 South Michigan Avenue” by the Rolling Stones, from their 12 X 5 LP. We needed a follow-up record for Chattahoochee Records. Samy Phillip [later known as Hirth Martinez] wrote a song, “Evil Love.” We went in and did it. Then Bruce Morgan said, “Okay, what’s the B-side?” And we looked at each other. We didn’t even think of that.

I suggested that we cut “2120” as a cover. Then Romeo Prado, the trombone player in the group, said we had to change it, you know. “Let’s put some horns on it.” Romeo is the architect of Thee Midniters’ sound. We also knew the value of instrumentals. Like, there were surf music instrumentals. The instrumental is not a novelty in East LA. We were following James Brown. “Night Train,” those type of things. “Harlem Nocturne.”

The street Whittier Boulevard became a cruising mecca. They started coming from Orange County and the San Fernando Valley, and from the beach cities. Our audience was everybody. They’d come from San Pedro, Hermosa, Manhattan Beach, Van Nuys, Pacoima. They would come to Whittier Boulevard partly because of our song, but we also had three things in common: music, cars, and girls. You could find all that on Whittier Boulevard.

We weren’t throwing beer bottles at each other as the highway patrol and the sheriffs tried to make it out to be when they started to shut Whittier Boulevard down. There was actually an article in the LA Times where they blamed it on Thee Midniters’ “Whittier Boulevard” song. There was always white fear. Before Mayor Sam Yorty, it was Chief Parker. This goes back many years.

Thee Midniters had strong support from the local DJs. Art Laboe, Huggy Boy, [and] Godfrey, as well as Sam Riddle on KHJ and Casey Kasem and Dave Hull from KRLA, took us to the air force bases. We were Casey’s favorite band to book. He was an advocate of what we did, and then Dave Hull, and then Sam Riddle. They hired us for their private events and the dances they sponsored.

We were not stuck in a doo-wop bag, either. We were total entertainers. We played a lot of backyard, family-oriented parties. The older folks wanted to hear boleros; they wanted to hear corridos. Then you had the second generation that wanted to hear Duke Ellington and big band stuff—Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby stuff. We learned all that stuff. Because music really transcends borders and colors. I think our band was indicative of that. If you saw the band, you left as a fan.

We were a very versatile band. We added percussion and a horn section, before Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears. Johnny & the Crowns had a full horn section, but they never got recognized. If the audience was predominantly black, we could knock out some R & B like anybody else, like “Sad Girl” and “The Town I Live In.”

We played everywhere. We were able to go to Thousand Oaks and to Hawthorne for the Drop. We performed at the Rendezvous Ballroom on Balboa Island with Dick Dale. We toured a short season with Paul Revere & the Raiders in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

Thee Midniters played with the Turtles at the Rose Bowl. We used to hang out with the Lovin’ Spoonful whenever they came to town to play the Trip. Also, Them with Van Morrison. We actually took Them and Steppenwolf to East LA and the Big Union Hall in Vernon. Bought them a quart of vodka. We hung with the Young Rascals every time they were in town. Eddie Brigati of the group would come to East LA.

We auditioned at most of the clubs on the Sunset Strip. But, at the time, they didn’t know what to do with an eight-piece band. That was not common. They were used to trios and four pieces, or four pieces with a singer. We were with the William Morris Agency for a little bit. RCA Records was checking us out when we opened up for Jose Feliciano. When we did our songs then, they were popular music and not oldies.

We did the Teenage Fair in Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard, and the audiences were all white kids. They were looking at us like we were aliens from outer space, some of them making really derogatory comments. “Where are your burritos?” We would hear stuff like that and ignore it, because we knew, as soon as we started playing, they [would] change their minds about us. That was our attitude. As soon as the music hit, they gravitated towards us. Sometimes they couldn’t get us off the stage. They kept calling us back.

Going to Hollywood was utopia for us. We grew up color-blind. Okay, even when the Chicano movement started, and the Brown Berets and those political factions would come and tell us that we were being exploited by the white man and whatnot, we never felt that. We were working. We were recording. We were sitting with record company executives. What they were saying to us didn’t register. We weren’t experiencing that, man—their whole concept and portrayal of what was going on in the world. We would hear them out and then have discussions about it. We didn’t get political with it. We took it someplace else after guitarist George Dominguez said, “I never knew we had it so bad.” George, drummer Danny LaMont, and I even wrote a tongue-in-cheek song, “I Never Knew I Had It So Bad,” for our third LP, Unlimited, on Whittier Records.

MARK GUERRERO: In 1959, when Ritchie Valens died, I was aware of it. I was ten. But what was so cool about “La Bamba” was that it was the first time you could listen to KFWB radio and hear something in Spanish. Something we knew [was] that he was a Chicano. It meant a lot to the community and inspired a lot of people to get guitars. I got my first guitar when I was 12. My dad bought it for me in Tijuana for eight dollars.

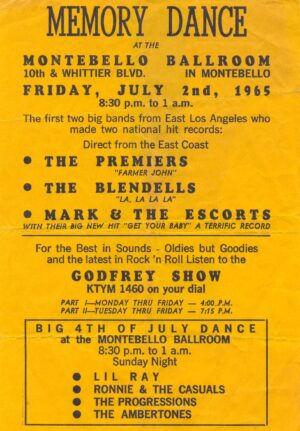

I was an East LA kid from the scene that had Cannibal & the Headhunters, the Blendells, the Premiers, Thee Midniters. We loved the Blendells. We had the same manager, Billy Cardenas, so Mark & the Escorts were on the bill with them several times.

We did “Get Your Baby” for the Rampart label. We played with Cannibal & the Headhunters. I was proud of them, and they had a hit record, “Land of a Thousand Dances.” I saw them open for the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl, and they were the only act that got any response at all. They were a dancing vocal group, like the Temptations.

Thee Midniters were probably the most popular group in East LA at that time, even with these other groups having hits. They got screams. They had the look; they were polished and smooth. Little Willie G, I always looked at like a Frank Sinatra—a skinny guy who sang ballads. That was his strong suit, and still is. The girls screaming. We liked them. “Whittier Boulevard” was a local and national hit.

Billy Cardenas describes himself as a vato from East LA, this street kid. He just loved music. He took a lot of guys—for example, the Premiers, these lowrider kind of guys. Pachuco kind of guys. They were playing in the backyard, [and Billy] polished them up, got them in suits—sort of like what Brian Epstein did to the Beatles, but Chicano style. He managed so many bands. He was a record company owner and kind of a record producer sometimes, but more the manager. But Billy also was in the studio producing.

I’m just saying, if it weren’t for Eddie Davis, none of that would have happened. We needed his record labels, and getting the stuff out … his record savvy that created the Blendells and Cannibal and the Headhunters, it was essential. And we needed Billy because he was out there in the trenches, finding these groups and grooming them.

I was at all the classic recording studios: Gold Star, RCA, one time at Columbia with Little Ray [Jimenez]. He’s very important, and did “I Who Have Nothing” on Donna Records, later distributed by ATCO. Arthur Lee, before Love, wrote the B-side “I’ve Been Trying.” Lee [and Johnny Echols] also wrote and worked with Ronnie & the Pomona Casuals on a recording.

East LA was always part of the music world. The Byrds played East LA College in 1965. I later saw Linda Ronstadt do a show there. Sonny & Cher, when they were Caesar & Cleo, performed all around the area.

In 1964, my dad, who was a singer and songwriter [Lalo Guerrero, the father of Chicano music], received a phone call from producer Don Costa asking him to come to Western Recorders on Sunset, where he was working with Trini Lopez. They wanted him to write a Spanish lyric to a song Trini was recording, that my dad titled “Chamaka.”

Dad invited me to come with him to the session to help Trini with the lyric. I invited Richard Rosas from my band, Mark & the Escorts, to come along. We arrived at Western Recorders and were led into a big studio, where Trini was about to sing with a large orchestra. Strings and the whole deal. There might have been some Wrecking Crew guys in the band, but I didn’t notice them at that age. We met Trini and Don, which was pretty exciting for me and Richard. We were only fourteen years old and in some pretty impressive company.

We watched the session for a while, and then Richard and I went wandering through the hallways when I see these two blonde guys. “Are you Jan and Dean?” And they said, “No. We’re the Beach Boys.” It was Al Jardine and Mike Love. They said, “Come on in.” They didn’t know who the hell we were.

We walk in, and lo and behold, there was Brian Wilson at the board and all the other members. Nobody else. They were recording the song “All Summer Long,” and about to overdub some vocals. They were all around the mike, and we’re just sitting there in the control room, in front of the mixing board with Brian Wilson.

On a break, Dennis Wilson came over and handed us a couple of singles with picture sleeves of their soon-to-be-released “I Get Around.” I asked him to sign it, and Mike as well, on the back of the picture sleeves. We were thrilled to get the records signed. Then “I Get Around” went to number one on June 6, 1964.

Richard and I were sort of East LA music kids from the scene that had Cannibal & the Headhunters, the Premiers, [and] Thee Midniters, and here we are meeting the Beach Boys, purely by chance. And they couldn’t be nicer. We went back to the Trini Lopez session, which came out great. It was quite a night for a couple of teenage Chicanos from East LA. Mark & the Escorts and the Beach Boys both played the Rainbow Gardens in Pomona.

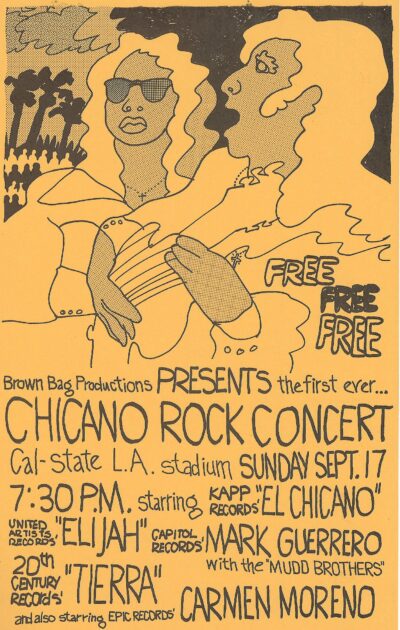

In September of 1972, another collection of regional musical voices was heard on the campus of Cal State Los Angeles, courtesy of Art Brambila’s Brown Bag Productions. There was an emerging world with an emphasis on Chicano culture and self-identity.

On September 17, 1972, there was a historic concert in the stadium at Cal State LA, in East Los Angeles. The artists included El Chicano, Tierra, Mark Guerrero with the Mudd Brothers, Elijah, and Carmen Moreno. The concert was organized by Art Brambila, who was the manager of Tierra and myself. The concert was the culmination of a two-day, student-sponsored cultural event called Feria de la Raza (“Fair of the People”). Featured was the cream of the crop of LA Chicano artists of the time.

El Chicano had become nationally known with their hit “Viva Tirado.” Tierra had just finished their first album on 20th Century Records. I had two singles released by Capitol Records that year as a solo artist backed by the members of the Mudd Brothers. Elijah had just released a great album on United Artists Records. Carmen Moreno was a world-class vocalist with Epic Records. The lineup reflected the diversity in LA Chicano music. El Chicano’s style contained elements of Latin, R & B, and jazz. Tierra combined elements of Latin, R & B, and rock. My band and music could be described as rock and country rock. Elijah was a funky horn band. Carmen Moreno was a folk singer, both in English and Spanish. The musical event was free to the public, so there were never any attendance figures. However, the football field and stands were virtually filled.

The Feria de la Raza concert is now considered historic because, as it says on the event’s flyer itself, it was the first Chicano rock concert. There had been many shows with multiple Chicano artists, but they were shows in theaters or dance halls. This was a post-Woodstock-style outdoor gathering with festival seating and the scent of cannabis wafting through the air.

The quality of the music and the future accomplishments of the artists make it a significant event in Chicano rock history. El Chicano went on to have another major hit with “Tell Her She’s Lovely” in 1973. Tierra had a major hit with “Together” in 1980, and played Carnegie Hall.

I went back to school at Cal State LA, earned a bachelor’s degree in Chicano studies, and continued my musical career. My bass player, Rick Rosas, went on to play extensively with Joe Walsh and Neil Young. Elijah went on to record another album produced by rock legend Al Kooper. Elijah’s horn section played with Neil Young on his This Note’s for You album in 1988. Carmen Moreno won a National Endowment for the Arts award and performed at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC in 2003. All the artists continue to perform to the present day.

I wrote and recorded “I’m Brown” for Capitol Records in 1972. The single, with the original lyric manuscript and picture of the band, was in the Grammy Museum in 2009, in an exhibit called Songs of Conscience, Sounds of Freedom.”

Mark Guerrero.

© Harvey Kubernik 2022

Dedicated to Tommy Davis and Joe Messina.

All images courtesy Mark Guerrero.

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows published in 2014 and Neil Young Heart of Gold during 2015. Kubernik also authored 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, David Leaf, Dick Clark, Curtis Hanson and Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

Kubernik is active in the music documentary world. In 2020, Harvey served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood that debuted on the M-G-M/EPIX cable television channel.

During 2022, Kubernik was an on-screen interview subject and received a consultant credit for the rock & roll revival music documentary currently in production about the story of the Toronto Canada 1969 festival at Varsity Stadium featuring the debut of the John Lennon and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band and the Doors. Klaus Voorman, Geddy Lee of Rush, Alice Cooper, Shep Gordon, Rodney Bingenheimer, John Brower, and Robby Krieger were filmed by director Ron Chapman.