-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Paul Krassner 1932-2019

By Harvey Kubernik

Paul Krassner, the writer, investigative satirist and free speech advocate, who published the groundbreaking counterculture periodical, The Realist, died at his home after a brief illness in Desert Hot Springs California on Sunday, July 21, 2019.

People magazine cited Krassner as “the father of the underground press.” The activist and author replied, “I immediately demanded a paternity test.”

Krassner was hailed by in the pages of Playboy: “Krassner lives in a world where Truth and Satire are swingers, changing partners so often you never know who belongs with whom.”

George Carlin and Lenny Bruce admired Krassner’s work and were inspired by him. Krassner interviewed Bruce for Playboy in 1959 and became a confident of Bruce and edited his autobiography, How To Talk Dirty and Influence People.

Krassner was born April 9, 1932 in Queens, New York. In the 1950s he studied at Baruch College in New York, before embarking on a stand-up comedy career booked as Paul Maul. He started his self-published journal The Realist, in 1958. His literary career actually began at Mad magazine and writing for The Steve Allen Show. The Realist developed a forum for a satirical view of America, and Krassner provided an outlet for his group of friends that included Lenny Bruce, Groucho Marx, Norman Mailer, Phil Ochs, Timothy Leary, Terry Southern, Dick Gregory and Mae Brussel, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin with whom he founded the Yippies, (Youth International Party) in 1968. The Yippies protested America’s involvement in the Vietnam War at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

In the mid-90s he penned his autobiography Confessions of a Raving Unconfined Nut, and also published a new collection of satirical essays called Winner of the Slow Bicycle Race.

He was a leading voice to decriminalize marijuana for many decades. Additional titles under his name are Pot Stories for the Soul and Psychedelic Trips for the Mind.

In 1998 Krassner along with Wavy Gravy were spotlighted in an exhibit at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame I Want to Take You Higher: The Psychedelic Era 1965-1969.

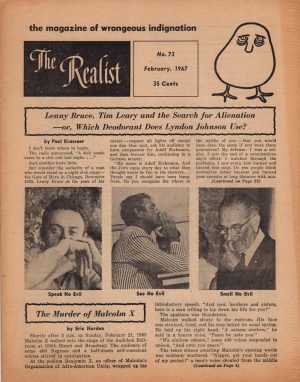

During 2004 I interviewed Paul Krassner in Venice, Ca. After an 11- year hiatus, his pioneering social newsletter, The Realist, active from 1958 to 1974, was reincarnated as a newsletter in 1985. “The taboos may have change,” Krassner suggested, “but irreverence is still our only sacred cow.” It ceased operation in spring 2001.

Krasser in 2005 was nominated for a Grammy for the liner notes he wrote for a box set of Lenny Bruce recorded performances and interviews, Let the Buyer Beware. In 2010 the Oakland branch of the writers’ organization PEN honored Paul Krassner with their Lifetime Achievement Award. In September 2019, Zapped by the God of Absurdity: The Best of Paul Krassner is set for publication.

Paul Krassner has been performing and lecturing around the United States for decades. In 1995 he recorded

During 1995 I literally ran into Paul Krassner one sunny afternoon at the Venice post office in Southern California, and fell by his pad for a chat afterwards to discuss Lenny Bruce, Jerry Garcia, Phil Ochs, John & Yoko, and his feelings about censorship of rock lyrics. He had just released We Have Ways of Making You Laugh, a spoken word/comedy CD, which was recorded live in Santa Monica, at the L.A. Bookstore.

Paul invited me to see him gig at the Ash Grove venue on the Santa Monica Pier. I found myself at a table with columnist Dear Abby, Abigail Van Buren, who came to the performance with political writer and commentator Robert Sheer.

One of the recordings’ strengths is that there are personal references to people like Jerry Garcia and Lenny Bruce, whose influence and impact on your written and stage work you acknowledge.

I had the opportunity to integrate Lenny because of that influence and the fact the album would be coming out on the 30th anniversary of his death. Groucho Marx once called me Lenny Bruce’s successor. It’s like you are part of a myth and handed some kind of torch.

The CD wasn’t hard to edit. It fell into place. I wanted to include my trip to Egypt with the Grateful Dead, part of which was included in my autobiography. Ninety-seven per cent of the recording was taken from doing it live, then into print. But the other three per cent I wanted to make conversational. If someone in the house said something, I wanted to be able to extend on it and get that immediate feedback.

Does censorship of rock lyrics infuriate you?

Any kind of censorship. I remember the ads they used to take in Rolling Stone which showed somebody in prison, “But They Can’t Bust Our Music.” But they did. On my recording, I discuss free speech and Tipper Gore. You don’t hear much about Tipper Gore anymore. I think she’s in the basement of the White House, censoring lyrics. By now, they’re up to gospel songs. “Go down Moses!… We can’t have this!” Free speech existed before the First Amendment.

Your onstage style is conversational, engaging the audience, rather than speaking at them.

The audience are your peers, not your inferiors. And a lot of performers treat them like that. When Lenny would meet people, he wouldn’t do shtick. He would ask questions and learn. And then sometimes that would become part of his act; the dialogue that ensued. Lenny’s exact words were: “I am part of everything I indict.” He made it a point to try to never get a laugh because of a four-letter word. He’d be doing a character and for that aptness of character, he would use the language or he would analyze the language. Many comics today get their laughs with profanity, on the beat. I was just at the Montreal Comedy Festival. 350 stand-up comics and the janitor had to come up onstage to sweep the dick jokes off the stage. But there were a few that shone out in the midst of it.

I learned a great deal from Lenny. When I first started performing, I was billed as Paul Maul, and he told me to use my real name. I learned compassion from him. He would take things from the point of view of the villain, you know, and carry it to the ultimate. He had empathy for all points of view. It didn’t necessarily get laughs, but he became a communicator, not just a comedian.

When I first met him in 1959, Lenny would come out with a newspaper headline, or he’d play “Spanish Harlem” from a record when he came on stage. He would do “show and tell,” things like that. Later on, it happened to be his legal briefs that he would be doing. I started off with an envelope of press clippings and I would just go off on that. And after a while, I dropped the clippings.

You’ve always had a relationship with music audiences. From club dates to shows with Phil Ochs, the Grateful Dead, and the recent Ash Grove booking.

I did many anti-war rallies and civil rights demonstrations. It’s funny, when I met Jackson Browne he told me his mother used to read The Realist. That was a jolt of reality. It’s fun to share a stage with people you honor. As a violinist, I played Carnegie Hall at the age of six.

I was friends with members of the Grateful Dead and hung out a lot with Ken Kesey, who said: “Why don’t you come to Egypt with us? The Grateful Dead are gonna play the pyramids.” On the first night, backstage, Jerry Garcia said to the band: “Remember, play in tune.” It was outstanding. Kesey said: “Did you see that? The Sphinx’s jaw just dropped.” The excitement was unspeakable. The band could feel it because it had been built from the ground up, just like the pyramids.

You also had a relationship with Yoko Ono and John Lennon.

Around 1972, Mae Brussel wrote an article about the Watergate conspiracy for The Realist. The printer, instead of the usual credit arrangement we had, insisted on $5,000 cash in advance before the issue went to press. I didn’t’ have the money.

I left the printing plant, ironically, with an inexplicable send of confidence. When I got home, the phone rang. It was Yoko Ono, whom I’d known in the ‘60s as an avant-garde conceptualist artist. I even gave her money once for one of her more absurd projects. She later gave me a personally revised alarm clock. Yoko had married John Lennon and the two of them were in San Francisco and invited me to lunch.

At the time, the administration was trying to deport him. I brought along the galleys of the Mae Brussel article and mentioned my printer’s ultimatum, and they immediately took me to a local branch of the Bank of Tokyo and withdrew $5,000 in cash. Later, they spent a weekend at my house in Watsonville. They loved being close to the ocean. John was a very curious individual. He loved hearing and telling stories. Very down-to-earth and simple.

We were sitting around smoking marijuana and opium and I remember that Lennon was holding on to the joint and that I wanted to phrase it very carefully when I said to him, “In England, do they say ‘Bogart that joint’ or is that an American expression since Humphrey Bogart was an America actor who dangled a cigarette on his lips?”

And Lennon looked at me with a twinkle in his eye and said, “In England, if you remind somebody else to pass a joint, you lose your own turn.” At first, I thought that was true, and then I realized it was his own little twist on things. But a lot of people we are talking about actually have this one thing in common. They were playful and had a spiritual bent, which are two sides of the same coin. Humor was part of their spiritual path.

You also knew singer/songwriter, Phil Ochs. You wrote his obituary for Crawdaddy! magazine.

I started the obit with the quote from a Mose Allison song, “If You Live, Your Time Will Come.” I always go back to that.

Phil and I became friends when he asked permission to write a song, “The Ballad of William Worthy,” based on an article in the Realist by a journalist whose passport had been revoked. He was a journalist in college, an editor. He had a sweet voice. “Changes” and “A Small Circle of Friends” have a lot of irony. Really pretty love songs as well as political tunes.

He’s one of those people who are still with me. On occasion, I’ll hear Lenny say, “Don’t tell that joke, it’s a cheap shot.” Or I’ll go to an afternoon movie alone, and Ochs will have a reaction to the film.

In fact, the first big Vietnam Teach-In in Berkeley, I was the master of ceremonies and convinced Jerry Rubin to bring in Phil Ochs. He hadn’t heard of him. I told Jerry it would be appropriate music between speeches. They became good friends and went to Chile together.

© Harvey Kubernik, 2004 and 2019

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 15 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018. It has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research. During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

Harvey’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr Motown, that initially was published in 1995 in Goldmine and HITS magazines is included in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett to be published in 2019 by Oxford University Press.

This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century. In November 2006, he was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by rhe Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.