-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Remembering Michael Nesmith

By Michael Lynch

“The one with the hat… “the one whose mother invented liquid paper”… “the one who didn’t do the reunion tours with the others”… “The one who pioneered country rock”… “the one who sowed the seeds for what became MTV”… “the one who led the fight for musical creative control for his band” are some of the ways he’ll be remembered. Or simply as the one directly responsible for a good-sized chunk of the Monkees’ musical pleasures and treasures.

The Monkees’ multi-talented singer songwriter and guitarist Michael Nesmith died of heart complications on December 10, 2021, a few weeks shy of his 79th birthday. Fellow Monkees Davy Jones and Peter Tork passed in 2012 and 2019 respectively. Only Micky Dolenz now survives.

All four Monkees had their unique traits, but right from the beginning, Nez stood out, both onscreen, with his signature wool hat, and cool collected demeanor displayed on their popular 1966 to 1968 TV series establishing him as the foursome’s leader, the smart one, and the one to take charge when the situation required, and offscreen, for Mike, who (like Davy) had already released a few singles released on Colpix Records, a branch of the Columbia and Screen Gems family tree, was writing and producing songs for the band’s records as early as the very first album, at the same time seeing his compositions recorded by other artists, notably “Mary Mary” being tackled by the Butterfield Blues Band and later “Different Drum” bringing Linda Ronstadt, by way of the Stone Poneys, her first visit to the upper regions of the charts.

The Monkees’ records sold millions, but Mike, horrified by some of the songs chosen by their musical supervisor Don Kirshner and resentful of the use of studio musicians providing the instrumentation instead of the Monkees (and smarting from the outcry and scorn once this became known to the public) sought to turn things around. He led his three bandmates in a bumpy, contentious but ultimately successful coup against the powers that be to give the Monkees musical control and have Kirshner dismissed. Fans can (and do) debate whether the Monkees were wise to rock the boat, but Nesmith followed his heart and creative instincts.

Traces of country influence could be detected as early as Mike’s songs on the Monkees’ first album, and as the years went on, Mike worked harder at balancing country with rock, improving as he went, by decade’s end all but providing the blueprint for ‘70s bands like Poco and Eagles (while Mike’s post-Monkees combo the First National Band continued down said course).

For decades Mike appeared reluctant to embrace his Monkee past, more keen on moving. Micky, Peter and Davy reunited in 1986 but Mike only appeared with them sporadically. He rejoined them to work as a foursome in 1996 for an album and a European tour the following year, but immediately jumped ship at that tour’s completion. The four never worked together again. Following Davy’s 2012 passing, Mike teamed up with Peter and Micky for a series of tours, and from then on right up to one month before his death, Mike was more often than not an active Monkee once again.

Close associates of Mike claim that in his final years Mike had achieved a fuller appreciation of what an impact the Monkees had made on so many. Perhaps in his mind he echoed his 1968 sentiments: “Here I stand, happy man.”

NOTABLE NEZ: TEN OF MIKE’S MEMORABLE MONKEE-SHINES

Everybody knows “Mary Mary,” “Listen to the Band” and “You Just May Be the One,” but Nez had plenty more delights up his hat. Here are ten other examples of Mike’s Monkees-era. Not necessarily his ten finest, but ten that taken together provide a decent summary of what, stylistically, Mike brought to the table:

SUNNY GIRLFRIEND (from Headquarters, 1967)

Dip the Rolling Stones’ “It’s All Over Now” in sunshine and add a touch of their unfinished early 1967 versions of “She’s So Far Out She’s In” (an early live favorite) and you have this upbeat gem that represents one third of Mike’s (wool) hat-trick of Headquarters highlights.

DON’T CALL ON ME (from Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones, Ltd, 1967)

Pisces had a higher percentage of Nesmith-related tracks than any other Monkees album, with many songs spotlighting him as either lead vocalist or songwriter. “Don’t Call On Me” was the album’s only song on which he was both. The song dated back to Mike’s earlier days as a folk singer, and tasteful recordings exist of his trio Mike, John & Bill doing the song in a gentle acoustic manner. For the Monkees’ version, the song is slightly amped up with increased instrumentation, but still kept gentle.

DAILY NIGHTLY (from Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones, Ltd, 1967)

Although Micky stars on this trippy track as lead vocalist and Moog player (one of the very first on a rock record,) the song itself came from Mike’s pen. His reflections of late 1960s Sunset Strip stand as some of his most poetic lyrics. Phantasmagoric splendor indeed.

CARLISLE WHEELING (recorded 1967, unreleased until Missing Links, 1987)

Mike recorded this song several times in his career. Attempts in 1967 and 1968 for the Monkees, once for his ambitious 1968 instrumental album The Wichita Train Whistle Sings, and then as “Conversations” for his 1970 post-Monkees album Loose Salute. To the ears of this writer, he captured it best the first time.

MAGNOLIA SIMMS (from The Birds, the Bees & the Monkees, 1968)

The same month Moby Grape Wow’d us with a simulated old-timey 78, so did the Monkees. “Magnolia Simms,” thanks to built-in surface noise, intentional scratches, and monaural sound panned to one channel (all explained in a back cover disclaimer) succeeds in, as Mike intended, capturing “the sound of the 1920-30 yippies.”

TAPIOCA TUNDRA (from The Birds, the Bees & the Monkees, 1968)

Originally found on the flip of “Valleri” before eventually finding its album home was what ultimately became the highest-charting Monkees song of his authorship, peaking at #34. A breezy charming mix of melody, whimsy and psychedelia…imagine “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” slightly faster, on acid.

SAINT MATTHEW (recorded 1968, unreleased until Missing Links Volume 2, 1990)

Do country and psychedelia blend well? They sure do on this originally-shelved track. The fiddles and twangy guitar combine fabulously with the organ and Leslie’d vocal of trippy lyrics, as if someone dosed the punchbowl at a hoedown.

NAKED PERSIMMON (from TV special 33 &1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee, taped late 1968)

Nothing demonstrated the two sides of Michael Nesmith better than his (sort of) solo spotlight scene of the Monkees’ infamous 1969 TV special. In an amusing split screen performance, hip electric guitar-toting Nesmith performs alongside a cowboy version of himself on a song that takes turns alternating between both musical styles. In addition to being one of the special’s more entertaining moments, it also accurately summed up where Nez was musically at.

WHILE I CRY (from Instant Replay, 1969)

Monkees fans long held this gorgeous tearjerker close to their hearts and were delighted when Nez revived it in 2021. The performances proved the earnestness of his delivery had not diminished over the 52-year gap.

GOOD CLEAN FUN (from The Monkees Present, 1969)

The final Monkees single while Mike was aboard was this country-drenched toe-tapper which lived up to its title. With health issues of Mike’s forcing an abrupt halt of his and Micky’s 2018 tour and causing great concern from fans, subsequent live performances of this song proved particularly poignant when Mike reached the thrice-sung final line “I told you I’d come back…here I am.”

Felix Cavaliere’s Rascals and the Monkees’ Micky Dolenz: Spring 2022 Tour

By Harvey Kubernik

Micky Dolenz of the Monkees and Felix Cavaliere’s Rascals are teaming up for live dates in 2022. Micky is fresh off the 41-date The Monkees Farewell Tour. Felix has a new album due soon and an autobiography coming in March.

Their trek kicks off January 22 at The Palladium in New York City and includes dates April 23 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Red Bank, New Jersey on May 12 and a May 14 appearance at the Patchogue Theater, Patchogue, New York.

A few years ago I saw the duo perform a stellar show in Los Angeles and excited they will hit the road together again.

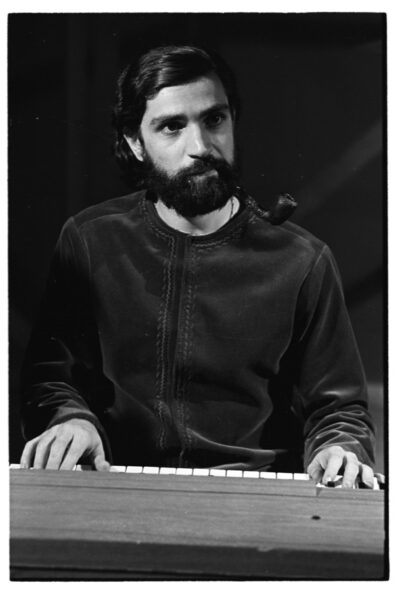

(Left: Felix Cavaliere. May 1968. Photo by Henry Diltz)

During 2013 I interviewed Felix Cavaliere of the Rascals. A portion of our conversation was published in Record Collector News magazine in Southern California.

“It’s one thing to make hit records and have hits. I always felt we had a different purpose out there,” volunteered Felix Cavaliere. “And I see people going through their past. And their healing processes and their memories of those years. And they start crying. What I see are people reaching out for what I call that ‘sixties’ positive energy.’ We get clobbered in the media for the sixties but you know what? There were good causes out there,” Cavaliere underscored.

About his Hammond B-3 organ, a predominant instrument in the Rascals lineup, Felix explained, “When I saw an organist playing and singing he was doing bass, rhythm, lead vocal. And I said, ‘This is really encompassing a whole part of the music spectrum.’ One of the beauties of the Hammond is that it sort of fills in the sonority area where the voices are. So when you have singers and Hammond there is a blend. It really fills a room with this beautiful sound. That’s what turned me on. The overall orchestration of the instruments. The Rascals had studio bassists on the albums, jazz session men. Like the Doors who employed a bass player on their albums.

“The band happened after hearing the Beatles… To me it was ‘I could do this.’ The first time I saw them early they were a band playing and singing live. They had not really done what they did with George Martin. I know they had great singers and the players are OK. But they were starting to write their own songs. They had great songs. I thought, ‘I can do this.’ And I wanted to get the best guys I could find. The best singers and musicians. And it worked. From inception to record deal was six months.

“That’s unheard of. Ahmet (Ertegun) courted us. So did Phil Spector. Seriously, I wanted to produce the group. Ourselves. That was the goal. I didn’t want anybody to take hold of this. The good luck was that Atlantic put into the room these geniuses, Arif Mardin and Tom Dowd. We opened Arif up to what he was capable of doing. The freedom was there. We had unlimited studio time. And our second record, ‘Good Lovin’ was number one.

“Initially when we were presented with ‘Ain’t Gonna Eat Out My Heart Anymore’ I kind of had a crazy reaction to the songwriters coming in. ‘Cause I wanted to write our own songs. But we hadn’t gotten to that point yet where we could start demanding stuff. The songwriters on ‘Ain’t Gonna Eat Out My Heart Anymore’ had a nice soulful thing and were Motown writers. ‘Hey, I’m a kid. Let me learn here and take it to the next step.’ I wanted to do our own thing and from the beginning that was my plan. And again, it was Beatles-stimulated. No question about it. All those English groups really opened the door for us and everybody.

“There is a different kind of pecking order once you have a big hit,” stressed Felix. “All of a sudden they have to listen to you a little bit more, you know. It was interesting and a bit pre-mature. In those days the only way you could work in a club was if you did other people’s songs. There was no way in New Jersey or New York you were gonna go in there and play originals. They’d throw you out on your heels. That was it. It was my job, our job, to come up with songs that were songs on the radio. And we had to fight for some of them like ‘Mustang Sally.’ They never heard that. But they were legitimately on the black radio stations and we brought them to the gig. What a place to test songs.

“When we played ‘Good Lovin’’ people got up and danced. So you kind of knew instantly what could be a hit record. If in fact it ever got to that level. You could see it and hear it. You had a built in Nielsen-type rating thing. But we had all covers. After that the spotlight was on us. And we had to follow a million seller. That’s not easy. The so-called sophomore jinx. So I really put my foot down, ‘You know damn it. We’re gonna write now. No more bringing outside stuff in.’

“We had a tough time. ‘You Better Run’ and ‘Come On Up’ came out. And, thank God, this woman came into my life and we started with ‘I’ve Been Lonely Too Long.’

“And, with ‘I’ve Been Lonely Too Long’ and ‘Groovin’’ at that point in my life I fell in love and I found a muse. It was just gaga land. I was gone. All of those love songs were about this one particular person. And it was so interesting and the culmination was ‘How Can I Be Sure.’ And then it was over. Things happen for a reason and the reason was to write those songs. That is what she was there for. The word muse is real. The stories were genuinely about being in love.

“There’s a certain divine thing that happens in every group,” posed Felix. “And Gene just fit. Initially he wasn’t funky but he learned. Dino was a wild horse drummer. And between (arranger) Arif Mardin and (engineer) Tommy Dowd they calmed it down. I didn’t have my recording chops together but Tom did. We overplayed, like all young kids and learned to chill.

“The thing about Atlantic Records was that it was not a corporate entity. The studios were open to anyone. No signs to keep out. One day Otis Redding sticks his heads in and says, ‘My God! They’re white!’ Which I loved. That was cool.

“At Atlantic everyone was jealous of us because we had eight-track. Can you imagine that? This is where you put the genius of Tommy Dowd. Forget it. He just knew and had tricks they had developed on the four tracks that we kind of inherited and learned. I learned from watching Tom. For example, you put the low bass and the high tambourine on the same track. And you can kind of make a change with EQ’s rather than overdubs and all that. Because we didn’t have any tracks, where to put stuff and how to blend.

“And don’t forget, stereo came in during that period of time. I found out that John F. Kennedy used to fly Tommy to the White House to do his press conferences. ‘Cause he was so enamored with his idea of stereo.”

© 2021 Harvey Kubernik

Felix Cavaliere. January 29, 1968. (Photo by Henry Diltz)

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, Neil Young Heart of Gold, Canyon Of Dreams, The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For November 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. This century he wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In November 2006, he was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the two-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted on EPIX television. In 2022 Kubernik is involved in several music documentaries and for the last decade is Editor-In-Chief of Record Collector News magazine.

Large as Life & Twice as Loud

Mike Brassard of Mike & The Ravens: January 15, 1943 – November 27, 2021

By Will Shade

Buddy Rich – or someone like him – once said, “It ain’t bragging if you can back it up” or words to that effect… but what if you’re not bragging. What if you actually try to hide your light under a bushel but it always explodes like a geyser of Roman candles? What if the moment you open your mouth in either conversation or song, people come to a halt and at the very least say to themselves, “Whoa, what in the world is this?”

That was Mike Brassard. He oozed charisma like mustard on a clean white shirt. He couldn’t help himself.

You were larger than life, Mike, and twice as loud. And you’ll always take twice as much room in my heart as anybody else.

So, how can I say goodbye to my best friend? How do I say goodbye to my brother from another mother? How do I say goodbye to a father figure? And how do I say goodbye to a guy I played air guitar with, a guy who was 25-years-older than me, but we both grinned like insane fools with Link Wray cranked to maximum volume as we danced our keisters off around the studio?

Well, you don’t say goodbye… you say hello to the memories, and there were so many memories…

He called himself the Big Bopper… I said he was a rock ‘n’ roll citizen in a hip-hop world.

I’d tracked Mike down in 2004 as I was putting together a compilation of pre-Beatles rock ‘n’ roll from New York and Vermont. While Mike wanted to tout the songs of his erstwhile partner, Steve Blodgett, he was reluctant to open up in regard to his own abilities. Anybody who knows me, though, knows that’s a futile endeavor. Before too long, I was flying down to Florida to spirit him north and into the confines of the Saxony Recording Studios.

It was that willingness to squelch his own genius that actually brought his character into sharper focus.

I miss Mike’s generosity of spirit… but mostly I miss his sense of humor… I remember him explaining what it was like to be the nominal adult in a band with Blodgett, Lyford and Young back in 1962.

“It was like babysitting the Three Stooges,” he said… there was no meanness in it… it was simply a statement of fact with some levity thrown in.

I won’t be saying goodbye to Mike. Daily I’m reminded of him. Yesterday I was watching a documentary on Sun Studios. My first instinct was to send him an email, raving about Jerry Lee Lewis… but then I remembered there was nobody on the other end of the line… I sent the email anyway.