-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

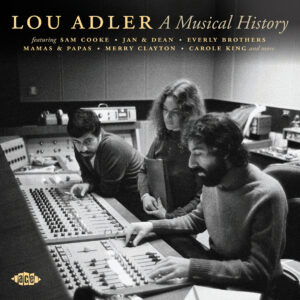

Lou Adler and The Roxy: 50 Years on the Sunset Strip

By Harvey Kubernik

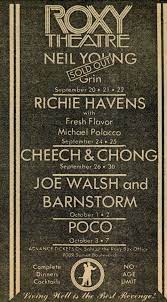

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Roxy and its enduring relevance, the Grammy Museum announced a new exhibit, The Roxy: 50 Years On The Sunset Strip, which explores the club’s origins and rich musical history. The exhibit opened on September 15, 2023 and will run through January 7, 2024.

“The Roxy and the Sunset Strip are deeply embedded in music history, and 50 years later, the Roxy continues to be a club where music’s most exciting moments still take place,” said Jasen Emmons, Chief Curator and VP of Curatorial Affairs at the Grammy Museum. “This exhibit highlights Lou Adler and the Roxy’s ability to tap into the cultural zeitgeist and lets visitors dive into the rich world of one of the most historic and beloved locations in Los Angeles.”

[Photo opposite: Linda Ronstadt, Lowell George and friends outside The Roxy, October 18, 1973. (Photo by Henry Diltz / Courtesy Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)]

The origin of the Roxy can be traced to a late 1971 rude awakening Adler received at the nearby Doug Weston’s Troubadour club when Carole King was making her debut at the West Hollywood nitery. The reliable club manager Robert Marchese, was not present the night when Adler, King’s manager, and owner of Ode Records, was informed twice that his name ‘wasn’t on the list,’ and curtly dismissed by a Troubadour doorman.

Lou mentioned the incident to his friend and mentor, Elmer Valentine, founder of the Whisky A Go Go with Mario Maglieri, and they decided that the Sunset Strip needed another venue, a rock club.

“I never went to Chuck Landis’ strip club, The Largo, but certainly was aware of Candy Barr and Miss Beverly Hills being up on the marquee,” reminisced Adler in a 2008 interview I conducted with him inside his Malibu office. “The only time I went into The Largo was the day that Elmer and I looked at possibly buying it. It became the Roxy Theatre.”

On September 20, 1973, Lou Adler and Elmer Valentine, along with Peter Asher, David Geffen, Bill Graham, Chuck Landis, and Elliot Roberts as advisors, opened The Roxy Theatre on the Sunset Strip. Neil Young and the Santa Monica Flyers initiated the club with a three-night stand, playing two shows every evening, and The Roxy quickly became one of the city’s premier clubs.

On September 20-21, 2023, Neil Young returned to The Roxy to mark its 50th Anniversary. Both shows benefited charities the Painted Turtle and Bridge School. On September 24th reggae artist Stephen Marley revived the 1976 setlist by his father Bob that was issued as Bob Marley and the Wailers’ Live at the Roxy.

Adler has also curated a Live at the Roxy album that features songs recorded from the venue. Tracks by Young, Bruce Springsteen, the Ramones, Brian Wilson, George Benson, Emmylou Harris, and Warren Zevon are included in the compilation.

The Roxy: 50 Years On The Sunset Strip highlights the Los Angeles institution’s legacy through artifact displays including Roxy memorabilia from Lou Adler’s archives, an original film, and photographs.

For more information regarding ticket reservations for the exhibit, please visit www.grammymuseum.org.

##

I was in attendance the night Adler and Co. opened the Roxy in September 1973.

Over the subsequent decades some of my favorite live shows Lou booked in the room were Bob Marley & the Wailers, Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band, Nils Lofgren, Captain Beefheart, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Chuck Berry, Eric Carmen, Jimmy Cliff, Robert Palmer, Flo & Eddie, Little Feat, the Crusaders, Smokey Robinson, Brian Wilson, Talking Heads, Cheech & Chong, Dion, Surf Punks, Peter Gabriel, Muddy Waters, and Teena Marie. One fan quipped after Teena’s performance, “Girl, they can retire that stage.”

Lou penned the Afterword of my 2008 book, Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon.

In the pages, he wrote, “For me it’s been an incredible journey, a life lived by simply traveling on Sunset: starting in Boyle Heights, through Echo Park, Silver Lake, Los Feliz into Hollywood, Sunset and Vine going in and out of Laurel Canyon, and continuing West on Sunset.

“The Sunset Strip ends at the Rainbow, and hopefully by that point you reach what you’ve been looking for, personally and artistically, and if you’re lucky, you get what is at the end of the proverbial rainbow.”

As for the legacy of Adler’s music venues, Lou mused in a July 2023 interview with Steve Appleford of The Los Angeles Times. “Oh, I think we’ll be here forever. It may turn into a building that houses the Roxy and has apartments. Whatever’s going to happen to Sunset Boulevard we’ll sort of go along with it, as long as there’s always a Rainbow, a Whisky and a Roxy.”

Lou Adler is identified inextricably with the musical culture of Los Angeles and Hollywood.

His fingerprints and commercially successful pop music retail endeavors have been heard nationally and internationally for over two thirds of a century.

With an uncanny feel for the public’s tastes and mood, Lou Adler has been at the forefront of launching such national and international trends related to rock-oriented genres; independent production, “boutique” record labels, live recordings, the singer-songwriter, surf and protest music, festivals, charities, films, comedy…theater and live music venues.

A lifelong Angelino, he has been honored by the Mayor and City Council of Los Angeles for bringing recognition to the City of Angels. In fact, by popularizing California pop culture, he did as much as anyone to entice the music industry to shift its base in the 1960s from New York to Los Angeles. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on April 6, 2006.

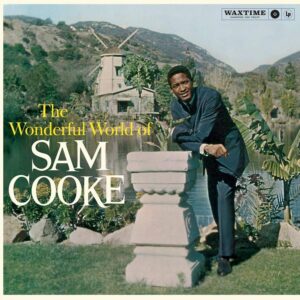

Adler produced the music and guided the careers of Jan & Dean, Johnny Rivers, the Mamas & the Papas, Spirit, and Carole King, as well as the comedy of Cheech & Chong, including The Mamas & Papas’ “California Dreamin’,” Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco (Wear Some Flowers In Your Hair),” Barry McGuire’s “Eve of Destruction,” Sam Cooke’s “(What a) Wonderful World,” and the ground-breaking multi-platinum, multi-Grammy Award winning Carole King’s Tapestry album.

As a multi-Grammy winner, he has produced 18 Gold and Platinum albums, including some of the biggest selling albums of all time; he has produced 33 Top 10 singles and co-written three Top 10 songs: “Honolulu Lulu,” “Poor Side of Town,” and “(What a) Wonderful World.”

Adler has produced for both the stage and motion pictures. Stage productions include The Rocky Horror Show, Zoot Suit, and Bouncers. His film credits as producer include: Monterey Pop, Brewster McCloud, The Rocky Horror Picture Show. In addition, he directed and produced Up In Smoke and Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains.

In November 2023, Adler will issue a live LP of the Mamas & the Papas’ full set culled from the June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival for Record Store Day via Orchard distribution, a division of Sony Music.

##

Lester Louis Adler was born December 13, 1933 on Chicago’s West side. His parents relocated to Los Angeles when he was 18 months old.

Adler grew up in the rough, melting-pot section of East Los Angeles called Boyle Heights. He attended Sheridan Street Grammar School, Hollenbeck Junior High and Roosevelt High School; at the latter, he was a prize-winning essayist and a student sports writer for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. He dropped out of high-school to join the Navy, where he earned the equivalent of a high school diploma. Adler enrolled at Los Angeles City College studying journalism and played basketball.

In 2008 and 2012 I conducted a series of interviews with Adler. Portions were published in two of my books: Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon and The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival.

Lou also invited me to write the liner notes to the 2008 deluxe edition 2 CD set of Carole King’s Tapestry, an album that sold over 24 million copies. Author, record producer and deejay Andrew Loog Oldham and I also wrote the liner notes to The Essential Carole King. Both products are available via the Sony/Legacy label.

“I met Herbie [Alpert] just after he got out of the army,” recalled Adler in his office in Malibu. “His girlfriend introduced me to my girlfriend, and that’s when Herb and I started hanging out together. Herbie, being a horn player, wanted to make a life in music. We started fooling around writing songs and this was going to be our job. We started talking about what he did and what I did, and we started writing songs. I had written one song before that. I wrote school songs, lyrics to existing songs. Then I had one attempt of writing songs with another lyricist.

“Jerry Leiber is why I went into the record business in the 1950s,” Adler gladly confessed. “I was at a place called Ben Pollack’s Pick-A–Rib on Sunset Blvd that later became the Body Shop strip club. Ben hosted these music jams-mostly jazz and Dixieland. And Jerry came in right off the street as he was on the charts with his partner Mike Stoller with ‘Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots’ by the Cheers. He was like a super star, a celebrity and the amount of girls who sat down at his table. Herbie Alpert and I exchanged looks. I said ‘this could be an occupation…’”

They formed a company Herb B. Lou Productions, a play on words on Desilu Productions. The B. was a reference to KFWB deejay B. Mitchell Reed, who they would manage for a brief period.

“We cut four demos we wrote that Herbie sang on. We started going around to companies on Sunset and Vine, because the three major labels were RCA, Columbia, and Capitol, you couldn’t get into those. They didn’t let us in. A&R men at the time were dealing with established songwriters. There was a music publisher, Sherman Music—before we met Bumps Blackwell—that published the four songs. We actually got covers off those demos. One was ‘Circle Rock’ for the Salmas Brothers on Keen Records, and Louie Prima’s band with Sam Butera recorded ‘Bim Bam.’

“Herb was recording as the Herbie Alpert Sextet for Andex Records—“Hully Gully” and “Summer School.” Andex was a part of the Bumps Blackwell scene. Bumps was then head of A&R at Keen Records, and Herb and I apprenticed under him at the label.”

The duo worked as apprentice A&R men at Keen Records under the tutelage of the legendary producer, Robert “Bumps” Blackwell. It led to a close personal friendship with Sam Cooke. Adler accompanied Cooke on tours backed by the Pilgrim Travelers, a gospel group that featured Lou Rawls.

“I first met Sam Cooke at the Orpheum Theater in downtown L.A., where LaVern Baker was performing,” remembered Adler. “Sam said, ‘So, you’re the new kid in town . . . ‘”

Record label owner Bob Keane first heard Sam Cooke singing in the Soul Stirrers in 1957. Cooke then notched a hit pop single, “You Send Me,” under the name Dale Cook on the Keen label. The nom de disque was an attempt to keep Sam’s voice and identity from the sanctified music community. No one was fooled. By the end of December ’57, the record had sold close to two million copies.

Adler lived for a while in 1957 with Cooke in Hollywood at the Knickerbocker Hotel. He also resided with Sam in an apartment on Saint Andrews Place in Los Angeles where George McCurn, Lou Rawls and Bumps Blackwell hung out.

In 1959, Adler and Alpert produced their first hit record, Jan & Dean’s “Baby Talk,” which became a Top 10 single. In so doing, they were among the first handful of independent producers in the music business. That soon followed by their cover version of “Alley Oop” by Dante & the Evergreens, that also went Top-10.

In 1960, Cooke moved to RCA Records, and Adler and Alpert wrote their first song for him, “All of My Life.” Meanwhile, a song that he and Herb Alpert wrote with Sam Cooke “(What A) Wonderful World,” that he produced in 1960, was a Top Ten hit in 1961.

“Going back to my early days with Sam Cooke and Bumps Blackwell I was always a song man,” revealed Adler. “The first thing that Bumps, Sam’s producer, a man who came out of Seattle with Quincy Jones when he was 16 or 17, Bumps took us to school. He made us go through stacks of demos, made us break them down. ‘What was good about the first verse?’ ‘The second verse?’ ‘The bridge, and how do you come out of the bridge?’”

“Sam taught me a language on how to speak with musicians, not only verbal but sign language as far as where to go musically,” Adler told me in a 2008 interview for my book Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon. “Sam taught me where the drummer would go and when to layout. That was a language I had to learn and also the communication between producer and engineer. I had no musical or recording experience, so between Bumps and Sam is where I learned,” he underscored.

“Herbie and I started writing ‘Wonderful World,’ and then I finished it with Sam at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Hollywood. Sam taught me how to communicate with musicians when you’re not a musician. He gave me a body language for working in the studio. I went out with him as kind of a road manager with the Soul Stirrers—that included Lou Rawls. Herbie and I produced Rawls’s first pop record.

“Sam also introduced me to a black world in Los Angeles, because I roomed with him for about eight months, including the Knickerbocker. I learned more about the music and the people than I’d ever known, and I never experienced one bit of racial intolerance. People took me in because I was with Sam. We would go to the 5/4 Ballroom.

“No one really looks at Sam as a singer-songwriter,” insisted Adler. “His songs were not always personal experiences. Like “Twistin’ the Night Away.”

“First of all—Sam’s instrument. He was the voice of that era. A tremendous vocalist. Also, he had a tremendous charisma that just spewed out of him in the recording studio, the stage, wherever he was.

“One time we went to the California Club to see Ed Townsend, who had a hit with ‘For Your Love.’ He was up there singing that song, and, of course, getting a response. [He] tried to get Sam to come up onstage. We were just going for a night out. Finally, Sam came up and went into some gospel spiritual number. It was the first time that I saw the entire female audience get out of their seats and on top of their chairs. That was amazing. Charisma, I think, explains Sam in the right way. He had it walking into a recording studio, and he had it onstage. There was just something about him that was so beautiful.

Adler saw Cooke every Christmas and on their birthdays. Sam, along with the Everly Brothers played at Adler’s June 1964 wedding to actress/singer Shelley Fabares.

On December 11, 1964, Sam Cooke was shot to death at the Hacienda Motel on South Figueroa in downtown Los Angeles.

A funeral service was held in Chicago on December 18th. His body was then flown back to Southern California for a second service on December 19th at the Mount Sinai Baptist Church. Cooke was interred in Glendale, Californoa at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery.

“Sam is never talked about as a human being,” Adler emphasized. “He’s mentioned as the great soul singer that he was and the instrument that he had, and the fact that everybody from Otis Redding to Jackie Wilson emulated him, followed him. He was just a great human being, a great guy, a great buddy with a wonderful sense of humor…”

##

Lou Adler and Sally Mann at the Hollywood Bowl, April 1966. (Photo by Henry Dultz / Courtesy Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)

From 1958-1960 Adler lived in Laurel Canyon on Lookout Mountain Drive.

“I never saw anybody. I lived there for quite a while. Then there was a big crash or a fire, and then I saw all my neighbors. Herb Alpert and I were partners around that time and we were working with Jan & Dean. We had an office on Sunset Blvd next to Ben Pollock’s. It was close to where I worked at Aldon Music on Sunset.

“At my place all the time was Joe B. Mauldin, the bass player of the Crickets. He’d sit in front of the fireplace. Laurel Canyon and Sunset was the hub. You had everything, you could eat at Greenblatt’s delicatessen or the counter at Schwab’s pharmacy; and get a haircut at Cosmo Sardo’s-one of the first upscale hairdressers buy your clothes at Zeidler & Zeidler, a men’s shop, which I briefly managed, and hear jazz at Sherry’s.

“The first artist Herbie and I produced was Jan & Dean in 1959; the song was ‘Baby Talk,’ and it went Top Ten. I was tooling around town for a while in a white Thunderbird convertible. I didn’t have any money, but I seemed to have more things. I was still ‘Louie from East L.A.’ experiencing Sunset Blvd.

“I was at clubs like the Purple Onion where I saw Chico Hamilton, and Ben Shapiro’s Renaissance Club where I saw Miles Davis. In times to come I would see Lenny Bruce at the Interlude, and later Bobby Darin at the Crescendo, to name just a few.

“I met [deejay] Art Laboe around 1960. I had gone to his events at Scrivner’s as a customer. You would bring him records. We used to have groups play roller rinks. Phil Spector and the Teddy Bears did roller rinks. In East L.A. I grew up on R&B and jazz. I was into pop music and went to jazz concerts. One of my first big dates was going to Ciro’s on Sunset. I took a nurse. I was working at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital and going to Los Angeles City College.

“For me at three o’clock in the morning I was at Pink’s Hot Dogs on La Brea eating a hot dog, a hamburger, and a tamale. But I should be credited for bringing in meals from Patsy D’Amore’s Villa Capri to recording studios. A great Italian restaurant in Hollywood that Frank Sinatra bankrolled. We’d ‘take five’ for the Steak Sinatra to be served.”

In 1961, Adler relocated to Orange Avenue off Hollywood Blvd. He then became involved with the Crickets, the Everly Brothers, Snuff Garrett, and Liberty Records. Jan & Dean were with the Liberty label.

During 1960 Adler was then hired to run the west coast Sunset Blvd. headquarters of Aldon Music, a New York-based music publisher, founded by Don Kirshner and Al Nevins in 1958, home to some of the top young songwriters of the day.

At about the same time that Alpert decided to break away from producing to become an artist: Herb Alpert and The Tijuana Brass.

At Aldon, Adler worked with such songwriting teams as Carole King and Gerry Goffin, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weill, and Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield. From 1960-1963, he ran Aldon’s office. It was a three-year stretch during which Aldon had 36 Top-Ten records. In 1962 Adler produced the Top Ten single “Crying In The Rain” (a Carole King song) by the Everly Brothers, for whom he produced several sides.

While he was at Aldon, Lou also supervised the production of a string of hits by Jan & Dean that included “Surf City,” “Honolulu Lulu” (which he co-wrote), “Dead Man’s Curve,” and “The Little Old Lady From Pasadena.” The result was the definitive “surf sound.” Spearheaded by Jan & Dean and The Beach Boys, the surf music sound became California’s first home-based musical trend, complete with its own youth subculture, spreading the California surf scene across the nation and presaging the youth culture to come.

Lou first met Carole King in 1961, when he helmed Aldon Music (later Screen Gems-Columbia Music) when King and Gerry Goffin were staff writers.

“So, from the beginning part of my career in the music business I was a song man,” underlined Adler. “That was very important to me. When I’m working with Carole and she is playing me these songs, she is playing songs that are the best. From track to track, you don’t get a bad song. You might get one song that had a problem with sequencing, but for the most part they hold up piano and voice.

“At Aldon Music Lenny Waronker brought Randy Newman to meet me and I gave Randy a stack of Carole King demos. I thought that was the best education that anybody that wanted to be a songwriter could have. I mean, at one point I said to Snuff Garrett, who was producing Bobby Vee, ‘I’ll let you hear this, but you’ve got to give me the demo back,’ because they were keeping the demos.

“Well, the thing that she did in singing and playing – and she also sang all the parts that eventually would show up on the follow up records, the hits. Once a producer got a hold of her record, she pretty much laid out the arrangement, both instrumentally and the vocal parts that would end up on the record.

“Her demos when I first started working for Aldon Music, the way that we worked, Donnie Kirshner, myself and Al Nevins, and the staff would find out what particular artist that had a hit and was looking for follow ups.

“That assignment was then given to all the writers to go to their cubicles and knock out some songs. They were there from the beginning. And actually, wrote the song. I mean, she — History shows most of her hits, until she became a recording artist and wrote ‘You’ve Got a Friend’ and ‘So Far Away,’ were with Gerry Goffin. They didn’t just write records, like in ’58 and ’59, for Fabian and Avalon. But they wrote songs first, and then wrote the record and showed how the song should be interpreted.

“Gerry Goffin is one of the best lyricists in the last 50 years. He’s a storyteller, and his lyrics are emotional. ‘Natural Woman,’ ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’ both on Tapestry.

“These are perfect examples of situations, very romantic, almost a moral statement. Coming out of the 1950s, with the type of bubble gum music, and then in 1961, Gerry is writing about a girl who just might let a guy sleep with her and she wants to know, ‘is it just tonight or will you still love me tomorrow. Goffin could write a female lyric. If he could write the words to ‘Natural Woman,’ that’s a woman speaking. Gerry put those words into Carole’s mouth. He was a chemist before he was a full time lyricist. He’s very intelligent and obviously emotional.”

In my long distance phone call with Andrew Loog Oldham, I seized the opportunity to ask him about Aldon Music and the famed cubicle world tunesmiths.

“But you see, they were like gold dust, these demos,” proclaimed the record producer and author about those Goffin and King ‘demonstration records.’ “Those demos, I remember – to start with, the weight of the acetate and the weight of the playing, the suggestion of the playing. It was just the space that – the amazing ability, still, to leave space that suggested what someone should – I mean, Dusty Springfield should know.

“Lou and I were part of the new breed of producers who participated in a different way with the artists we record. But what Carole, the songs of Carole and Gerry Goffin and with whomever she was writing served was that old – in England, the Mitch Miller — Well, not Mitch Miller, because he was an accomplished musician. But the model of where the producer, be it Johnny Franz with Dusty Springfield, they would give it to the arranger and see what he came up with.

“And so, from the demo, the arranger did the parts, and the parts were there. I mean, when you heard – it’s like the ability – it’s actually the ability to sell. And we go back to like Tin Pan Alley and the people on the back of trucks, of flatbed trucks, playing — selling the sheet music. This is the gift that then permeated its way through people like Jerry Herman and Alan Jay Lerner and the writers of those times. And because it was the same streets as The Sweet Smell of Success there it was, on Broadway, in 1650 in Aldon –And that great gift, and the – I mean, Mitch Murray with ‘How Do You Do It?’ didn’t quite have it. Yeah. I mean, John Lennon at a piano, that’s a different story.”

When Aldon sold out to Columbia Pictures Music, Adler became VP of Columbia Pictures Music. He then left to form his own company, Dunhill Productions, which came to be distributed by Liberty Records.

##

Lou Adler and Johnny Rivers. (Photo by Jim Roup)

In 1964 Lou produced the Johnny Rivers album Live At The Whisky A Go-Go which became the company’s first release. It was not only the first live rock album it kicked off the world Go-Go craze of the ‘60s. The success of the album led to a string of Adler-produced Johnny Rivers hits, including “Memphis,” “Maybelline,” “Secret Agent Man,” and Top-Ten covers of Motown’s “Baby, I Need Your Lovin’,” and “Tracks of My Tears,” he co-wrote and produced Rivers’ number 1 record “Poor Side Of Town.”

“Rivers had started writing, and we were getting ready to record his next album, Changes,” recalled Lou. “And up until that time, he hadn’t written. He started the song ‘Poor Side of Town,’ and called me. ‘I’m sort of stuck on the bridge and the third verse. Do you have any ideas?’ I worked on it separately and gave him what I had. That was a number one record for him, and the first song he had ever written as a recording artist.

“Johnny Rivers is— and it might be cliché, it’s used in a lot of ways— but he’s an underrated artist. I mean, we must have had fourteen, fifteen Top Ten records. He’s one of those artists who always knew what was right for him. And that’s him. Choosing old material that had already been recorded, like ‘Memphis’ and ‘Maybelline.’ Berry Gordy told me that the Rivers’ covers of the Motown records, like ‘Tracks of My Tears’ and ‘Baby I Need Your Lovin’,’ they outsold the originals.”

In 2008, I interviewed engineer/record producer Bones Howe and we chatted about Adler, Rivers, the Mamas & Papas and Bill Putnam’s Western Recorders/United Western/United studio on Sunset Blvd. A favored location for Adler’s audio explorations.

By 1958, Studio B at United was complete, with two reverb chambers, a mix-down room, and mastering rooms, one of which had stereo.

“When Putnam opened his studio, the first thing he did was that he got a new Grampian cutting head [that] you could pump a lot of volume into,” clarified Howe. “You could really pump a lot of voltage and signal into it, and it would cut a much hotter 45 than the Altec head that everybody else used for cutting LPs and 45s. UREI was the development company, and a different division of United Recording. They developed a 1176 limiter, which I ran and did all the test runs on. He had a prototype, and gave it to me in the studio to use. United just became the place to record. Randy Wood of Dot Records worked exclusively at Studio B as well as Louie.

“Johnny and Louie put together ‘Poor Side of Town.’ Rivers was a performer first,” praised Howe. “He learned from the road. Johnny knew how to play in front of an audience. He was a good performer before he was a recording artist. Rivers came into the recording studio and was really raw when we did ‘Memphis’ and ‘Maybellene.’ We all caught a great period in time. I thought ‘Secret Agent Man’ when I first heard it was a gimmick. Sloan and Barri the writers were my friends and got them to get a record with Rivers by Louie. Wow! ‘We got Rivers to cut one of our songs.’

“The rhythm section had a lot to do with the records from Rivers. But that was part of River’s thing. He liked that country R&B. He was like a country singer doing R&B. Boy, he hit the record and radio market at just the right time. Chuck Berry songs, ‘Memphis.’ ‘Maybelline.’ He recorded them and made them his own. And Lou had the idea of bringing in Go-Go girls and background vocalists. That was part of something that was going on. So, we did those things with the hand claps over them. But the rhythm section was really strong and Johnny could deliver those tunes. Rivers had a real good voice.”

“Then in January 1964 my friend and partner, and the visionary of the Strip, Elmer Valentine, opened the Whisky a Go-Go,” stated Adler. “Headlining was Johnny Rivers.

“Later that year, Ciro’s went electric, and the whole street started dancing to rock ‘n’ roll. Elmer opened The Trip in 1965. I designed the outside of the club. We had the Top Ten records that we used to change weekly outside on display, and I cut the first music video, which unfortunately is lost. Elmer Valentine was a partner in the club. After two o’clock in the morning, Martha and the Vandellas came by Laurel Canyon after they played The Trip. When the Sunset Blvd clubs closed down, the action came up the street to Laurel Canyon. I came up with the name. It was from a movie Jack Nicholson wrote-I would meet Jack later in the ’70s.”

Following the success of Dunhill Productions, Adler set up Dunhill Records. His first production and release on Dunhill was Barry McGuire’s worldwide number 1 hit “Eve Of Destruction.” It was one of the first rock and roll protest songs and established a trend in socially-conscious rock music.

“I met Barry McGuire one night at Ciro’s. It was after the show. Barry had a conga line into the street and he had already been in the New Christy Minstrels. I put him together with songwriters PF Sloan and Steve Barri and asked them to write some kind of ‘Dylanesque’ protest song. They came up with ‘Eve of Destruction.’ Barry tipped me off to the Mamas & the Papas.”

In 1965, in his own words, Adler “uncovered” the Mamas & the Papas and subsequently gave the record world the songwriting talents of John Phillips.

These former folk singers were amongst the vanguard of the new music scene that was building in Los Angeles that included the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and the Doors.

Lou produced four gold and platinum albums for the Mamas & the Papas, including their classic hits “California Dreamin’,” “Monday Monday,” and “Dream A Little Dream Of Me.”

“A lot of the first songs of the Mamas & the Papas were written before I ever got to them,” described Adler. “The music was polished. It wasn’t raw. They looked raw, that’s back to the album cover, Can You Believe Your Eyes and Ears? What that meant was, ‘that sound was made by these people?’ John was never raw. He went to West Point. He came out of the Hi Lo’s and the Four Lads.

“John Phillips influenced me a lot on sequencing and what the final chord on one song is to the first note on the next one so it’s not jarring music transitions.”

Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot at the Monterey Pop Festival, June 1967. (Photo by Henry Diltz / Courtesy Gary Strobl at the Diltaz Archive)

“I’d met Lou Adler in Santa Monica California at The TAMI Show in late ‘ 64,” reflected Andrew Loog Oldham in a 2007 interview I conducted with him.

“He was managing the hosts Jan & Dean and I was there with the Rolling Stones. We became fast friends. About a year later I was in LA recording the Stones at RCA; Lou asked me to come down to his Dunhill records office on South Beverly Drive. In his office were four quite ordinary, very special folk. John Phillips, Michelle Gilliam, Denny Doherty and Cass Elliot.

“They sang about a dozen songs to the accompaniment of John’s acoustic guitar. They sang their whole career ‘California Dreamin’,’ ‘Monday, Monday,’ ‘I Call Your Name,’ ‘Creeque Alley.’ I heard ‘ em all. Lou smiled. ‘Whadja think?’ I thought a lot.

“I knew my mate had his Mick and Keith in one and that was what was important. The group was almost a backdrop to what Lou and John were about, changing the name of the game and keeping it interesting.

“I know about the hits. The national anthems, the weavings as in ‘Creeque Alley’ of the Mamas & Papas’ journey, but my total unabashed fave, the one that brings a lump to my throat and makes the pop hairs stand up on my hands is ‘Twelve Thirty.’ The sonic dark and dirty’ to the Canyon is just not only magical but real, and that was the art of John Phillips. The production, of course, is a result of the sonic marriage of Adler and the group. It’s their ‘Mother’s Little Helper,” suggested Andrew.

“I made suggestions like putting the girls on one side and the guys on the other side on Mamas & Papas,” explained Bones Howe. “That sort of stuff. ‘Let’s do it this way and see how it works.’ Those became concrete formats. And when I started working at Studio 3 at United Western, I invented that rhythm set up. Because what I found out is that if you put the guys close enough together, they’ll play better. And not only that, the sound will be better. Because the sound doesn’t have to travel as far to the other microphone. It’s all about an ensemble sound.

“Lou Adler and John Phillips along the line saw what was happening back east and knew they could make it happen in California. Lou is a business guy. He always tried to keep moving and look for something else and something new. After all those years with Johnny Rivers. Lou and John really studied what the business was about and had an inside view.

“I was in the room with Lou when he first heard the Mamas & the Papas. It was in the back room at Studio 2 at Western Recorders. And John had a guitar and sang four songs with us. Those four voices had a magic together. Denny had a beautiful voice and Cass had a good vocal. The mix of those four voices was so amazing. You didn’t need to do much in terms of enhancement. We doubled their voices up but it really was a great sound.

“I went back with Lou and the Mamas & Papas to the Barry McGuire recording session when they walked in for the first time and sang backup on ‘California Dreamin’’ They were four scruffy kids off the street with one guitar between them. I watched that whole relationship develop. Lou lived in Bel-Air and John lived in Bel-Air. There was a friendship that grew between the two of them that I didn’t realize had the depth that it did.

“Sometimes Lou would ask me about guys. Like on ‘California Dreamin’ he did not want to put a saxophone on it. He didn’t want a guitar solo. John (Phillips) said something about a flute. I said, ‘Bud Shank is in the back room doing a session. Bud Shank will play.’ Lou said alto flute. And Bud had an also flute. I asked Bud to come into studio 3 for our session and he made it in one or two takes. Guys like Lew McCreary played in the fifties with big bands. Lou Blackburn. And some of them managed to make the transition to playing with the small horn groups. There was a transition period in the late fifties into the early sixties where pop music was borderline R&B before surf music hit.

“Lou was well on his way before the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967, already had gone through the Dunhill Records thing. He understood how to do business. That was one thing he was really good at. I don’t think you can make great records with music you don’t like. You have to love the music and be inside of it to make hit records.

“Lou played a big part in my career,” admitted Howe. “When I started producing Louie was my mentor. I learned so much about what is in a producer’s head as opposed to what is in an engineer or musician’s head. I learned about the other side watching him bring up Trousdale Music and Dunhill Records. And you can’t be a hit producer if you can’t find great songs. Lou sitting and listening to all those demos at Screen Gems 1960-1963.”

##

After selling Dunhill, Adler started the Ode label. The initial releases were ‘Stoney End’ by the Blossoms, a group he had known since the late 50s when they sang background for Sam Cooke, and Scott McKenzie’s ‘San Francisco (Wear Some Flowers In Your Hair)’, one of the biggest hits of 1967.

“There was now FM radio as well, the exposure,” reflected Adler. “It was now beyond Top 40 radio with 13 records played an hour to get three commercials and the additional exposure of the LP all of those things. The artists wanted to express themselves more in terms of album covers, advertising, And, perform in places where the music meant something. And, writing their own songs.

“Although that started in 1964 with the Beatles really. The Beatles come in 1964, writing their own songs, Dylan looks up and says that you can write a good song and get it played and have a feel, he does it. The Mamas & Papas and Lovin’ Spoonful look up and say, ‘Dylan is doing this it’s OK for me now.’ You get more prolific writers coming in now. You get Sebastian, you get John Phillips. You get folk writers that had been songwriters before, not just record writers. So, that pretty much started it after 1961-1963, where you cut a track, put a good looking guy on the record, Fabian, Frankie Avalon, Jan & Dean.”

##

Lou and I discussed the landmark June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival.

“In 1967, Alan Pariser and Benny Shapiro approached John, Michelle and I for the Mamas & the Papas to headline a one-day one-night concert at Monterey. We said the Mamas & the Papas would only appear if the festival was for a yet to be named charity and that all of the acts would appear for no fees but full first-class expenses.

“Simon & Garfunkel completely supported the idea. I think Shapiro and Pariser understood the drawing power of those two acts. Benny wanted it to be a commercial event, so in order to eliminate the conflict he let us buy him out for fifty thousand dollars. Johnny Rivers, Paul Simon, Terry Melcher, John, and I put up ten thousand dollars each.”

In spring 1967, Lou Adler and his lawyer, Abe Somer, executed the legal paperwork for non-profit status for Monterey and now both on the Board of Directors for the festival. The Monterey Board of Governors listed Brian Wilson, Roger McGuinn, Donovan, Andrew Loog Oldham, Terry Melcher, Paul Simon, Alan Pariser, Smokey Robinson, Adler, Phillips, and Johnny Rivers.

On April 9, 1967 the Beatles’ Paul McCartney flew in from Denver, Colorado, to Los Angeles in a Lear Jet owned by Frank Sinatra. On arrival Paul visits the Bel-Air mansion of John and Michelle Phillips of the Mamas & Papas, a pad above Sunset Blvd formerly owned by actress Jeanette MacDonald.

“The motivation came that night at John and Michelle’s with Cass, Paul McCartney, myself and a couple of others; our conversation went to rock ‘n’ roll as an art form, like jazz,” said Adler. “John and I were both aware of the Norman Granz produced Jazz at the Philharmonic recordings. Someone said, ‘They aren’t taking rock ‘n’ roll musicians seriously.’ Rock ‘n’ roll was always viewed as a fad that would be over by the summer…but now it was more than just music, it was a lifestyle.

“We looked at Paul beyond an act. Beyond somebody that was singing on stage. As a composer. He was somebody not writing just hits, but great songs. Like ‘Michelle.’

“There were two meetings between the Mamas & Papas and Paul McCartney. The first one was in London in 1966. McCartney played piano all night. And he played on the strings as opposed to the keys. McCartney’s first recommendation (simultaneously along with Andrew Loog Oldham that same afternoon) was to book the Jimi Hendrix Experience since they were tearing up England at the time.”

“The Monterey International Pop Festival production office was on Sunset Strip in Hollywood and I was in self-imposed exile from the UK,” volunteered Andrew Loog Oldham.

“In late ’66 the Rolling Stones had returned to England for a rest after four years on the road. The drugs were working for and against us. Suggesting the Who had nothing to do with any friendship with (managers) Kit Lambert & Chris Stamp; in fact, we were not really friends at all, just nodding out acquaintances. We were all too busy. The Who and Jimi Hendrix. The minute after I’d said it either John or Lou said McCartney had said the same. As I said, it was obvious. Derek Taylor was the worker now, he was incredible. The dream was on. From the Manchester Evening News to the Mop-tops to Monterey Pop, all his skills revived and intact.”

“We were now The Monterey International Pop Festival,” Adler marveled in his Malibu production office.

“We were based at the Renaissance Club at 8424 Sunset Blvd …The Sunset Strip, across from Ciros. The Renaissance was formally a jazz club, and I remember seeing Miles Davis there. We now had three days in June, the 16th, 17th & 18th booked at The Monterey Fairgrounds, and three acts committed. The Mamas & the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, and Ravi Shankar who had signed a contract with Benny Shapiro, who would be the only act to be paid, as we chose to honor his contract.

Ravi Shankar, August 1967. (Photo by Henry Diltz / Courtesy Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)

“Paul Simon took a position from the beginning. He is on the Board of Directors and he had an invested interest in the festival because he put up ten thousand dollars. He also had an interest in what we were trying to do. He understood, he came aboard right away. We knew him for a while.

“We went up there two weeks before we moved into the Monterey Fairgrounds. At this point, it sounds crazy, ‘you can’t do the festival, you can’t get the acts, or work out the transportation,’ but that’s because there’s rules and regulations now. There were no rules then. The acts that we found had conflicting schedules like Dionne Warwick was already set to appear at San Francisco hotel.

“There weren’t a lot of tours. We’re still talking 1967. Not a lot of acts are working all the time. The San Francisco acts are playing around San Francisco. The big acts couldn’t get visas to get in. The Motown acts were working, the blues acts were working, but the acts that we went after, they had time even though we had a short window. That’s how bookings went. ‘What are you doing in the next two weeks? I’ve got a job for you in Hawaii.’ The timing and everything were in order. Whatever we wanted seemed to be available to us. FM radio became an alley. The album tracks replaced the single.

“Everyone jumped on very quickly. We tried for the Impressions. We got some no’s, from some of the Motown acts and Chuck Berry passed. I had Chuck on (earlier) tours and he’d stand right before the curtain. His hand would go out, you’d pay him, and he’d go on stage. That’s because he got burned so many times, he wasn’t about to do it. But to his credit, Otis Redding’s manager, Phil Walden, understood it immediately.”

The artists who appeared include: The Association, Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, Mike Bloomfield’s Electric Flag, Booker T & the MG’s, Buffalo Springfield, Eric Burdon & the Animals, Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Byrds, Grateful Dead, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Jefferson Airplane, Mamas & The Papas, Hugh Masekela, the Steve Miller Band, Moby Grape, Laura Nyro, Lou Rawls, Otis Redding, Johnny Rivers, Ravi Shankar, Simon & Garfunkel, and the Who.

“The festival was incredibly busy, productive, life-changing, exhilarating and relaxed; I do not think that ever happened again,” perceived Andrew Loog Oldham. “The focus was incredible; the mission was God given. We had never been given that type of responsibility before and there was no way our side was going to be let down. Monterey Pop gave service; it still does. I remain oh, so proud I was there and was a small part of it. Otis; the Who; Jimi Hendrix… every time I think of the music, I remember the sea of faces and the rhythm of one of the crowd. These white kids in the audience were in school. We all grew from the diversity presented in those three days.”

“And, for the most part, the artists were established at Monterey, except for some of the San Francisco groups,” reinforced Adler. “After Monterey, artists would demand and get preferential treatment. That’s one of the side benefits of the Monterey International Pop Festival-it taught the acts what it meant to perform under the right conditions and how to demand the right conditions in the first place. It was the first time any of this was done this way.

“Jerry Moss in the History of A&M Records book says that ‘until 1969 A&M never really looked at rock ‘n’ roll acts.’

“Shortly after Monterey they did. From an artist standpoint, and a lot of it had to do with the San Francisco groups, their mentality of what the record industry was, the way they looked at the industry, the way they were skeptical of the industry, if you’re gonna sign me here’s what I want.’ And that set a pattern. ‘I’ll tell you what my album cover is no matter what it costs to make it. This represents me.’ And those label heads had not dealt with this before said ‘yes, yes, yes.’ And, that went on for years to come.

“Over the years I’ve heard constant comments about Monterey, from a lot of the performers. Always thrilled about the event and a lot of remarks about the sound system we employed. I was on the road with acts and we’d get to the concert where there would be two small speakers and a microphone. Promoters would rent small and lousy sound systems on the cheap. But that went for everything. The turnaround, as far as the power became the act to promote their records, to the record labels, to advertising, album covers, amount of money, right or wrong, in 1967 or 1968 they got what they wanted.

“The Monterey International Pop Festival was, and still is, about the music and the artists who had break-through performances there, and how much impact they have had over these many years,” observed Adler. “It was the first major music festival. It wasn’t about the weather or traffic jams. It was and will always be about the music.”

The June ’67 festival also yielded the 1970 platinum album, Jimi Hendrix and Otis Redding at Monterey and the critically acclaimed 1969 D. A. Pennebaker film Monterey Pop, both were produced by Lou Adler and John Phillips. In late 2011, a Blu-Ray edition of Monterey Pop was made available by Criterion.

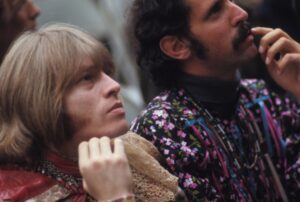

Brian Jones at the Monterey Pop Festival, June 1967. (Photo by Henry Diltz / Courtesy Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)

In my 2007 interview with Oscar-winning documentarian Pennebaker, he commented on the genesis of Monterey Pop.

“[Producer/director] Bob Rafelson (The Monkees TV series) called me up and he said ‘would you like to do a film of a concert in California?’ And I thought about it and I had just seen Bruce Brown’s Endless Summer, which is not about surfing at all, but all about California. Every kid out of high school the one thing they wanted to do was get to California, and Endless Summer didn’t hurt.

“I saw Rafelson once, maybe, but he was never involved. It was always Lou Adler and John Phillips that I dealt with. And we flew up with Cass (Elliot) to see the place and I looked at it and it was this tiny place. I had no idea what was going to happen there. I had never seen a music festival at all. Not even Newport, so I didn’t know what to expect. It had a really nice feeling to it and I loved Monterey and it’s a lovely place. And I sort of thought, ‘well these guys know what they are doing.’

“John and Lou. John was a total genius. He was part Indian and had a mystical view on everything he did. And he hadn’t been playing music for long. The Journeymen a couple of years before the Mamas & Papas. Everything he was doing was like he’d been touched and as long as the spell was there it just flowed out of him. I loved John. He was marvelous. Lou knew what he was doing and I knew he was a real good sound mixer ‘cause I had listened to some of the stuff he had done but I knew they were hatching a real interesting game.

“Which was from the beginning get rid of the money. That was the big thing. Get rid of the money. And I could see that that was gonna make it work. It was a very Zen thing but I can see that, and later I saw what happened at Woodstock, and I really didn’t want to get involved with that at all. One of the producers of Woodstock saw the film of Monterey Pop and wanted to do a festival.”

“When there was ten thousand dollars offered initially for us to headline a show in Monterey,” Michelle Phillips indicated to me in a 2007 interview, “we didn’t take the money, there wasn’t any money left for any support acts if we took this offer, we chose to go non-profit.

“And, I’ll tell you something, I don’t think the Monterey festival could happen if the money was on the table. I don’t think that concert could have ever happened if the performers were paid. I mean, where would all the money have come from to get them there and to pay them? I think that logistically it would not have worked. That’s when John and Lou came up with the idea of doing a charitable event. Because all of the artists donated their performances to charity, it resulted in the ongoing nonprofit good works of the first rock charity, (the forerunner to Live AID, Band AID and Farm AID) the Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation.

Since 1967 the Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation a non-profit endeavor continually supports and empowers arts organizations, music therapy programs and health care for musicians.

montereyinternationalpopfestivalfoundation.com

##

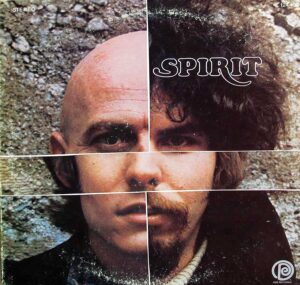

Following his mid-June 1967 triumph at Monterey, Adler in 1968 inked Spirit to his Ode label and produced their first three albums.

“The band had to be seen to be believed,” drummer Ed Cassidy told me in a 1975 interview published in Melody Maker. “Our LPs were pale by comparison. It was unique in a way, soft on record, and our stage thing was so concrete that more people got into us for that reason.

“The band was definitely ahead of the times in many areas. I even played differently than most of the rock drummers—a bastardized version of rock, incorporating my own trip. We were exploring new ways of improvisation; [Guitarist] Randy [California] and I were keen on that. The thing that was successful about Spirit was that we didn’t try to contrive any of the elements that appeared in the music. We weren’t rock ’n’ rollers, and we weren’t jazz. It just happened. The concept was mine; a group trying to blend all types of music together.

“I even played differently than most of the rock drummers; a bastardized version of rock, incorporating my own trip.”

Around the same time, Adler produced Dylan’s Gospel by the Brothers and Sisters. The lead vocalist on many of the tracks was Merry Clayton, who made her solo Ode debut with a cover version of the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” in 1970.

Peggy Lipton and Carole King would soon become Ode recording artists.

“Maybe the first sign that Carole King was set to make a definitive break with her successful but semi-anonymous identity as a Brill Building hit-machine came with ‘The Road to Nowhere,’ underscored author and journalist, Richard Williams, “a 1966 single full of drones, bells and angst which, despite being widely ignored, seemed to predict the coming sounds of both the Jefferson Airplane and the Velvet Underground.

“Three years later came Writer, an album that prefaced the era-defining Tapestry. As well as new compositions, Writer included songs already familiar from earlier versions by other artists: ‘No Easy Way Down’ (Dusty Springfield), ‘Goin’ Back’ (the Byrds) and ‘I Can’t Hear You No More’ (Betty Everett). King was letting us know that she was now ready to repossess her own material and step out into the world.”

By 1968 Carole King sought to resume her recording career. Recalling his enthusiasm for her Aldon demos, she approached Adler, who proffered a contract. Calling themselves The City, she and her fellow musicians recorded the album Now That Everything’s Been Said with Adler producing.

Adler’s work with Carole King was one of the most fruitful of his career. At the time of its 1971 release, Tapestry became the largest selling album in music history by a female vocalist (to date it has sold over 25 million copies world-wide and is still selling).

The LP struck an immediate chord with the public and ascended to #1, where it remained for 15 consecutive weeks, becoming the best-selling album of the 70s.

At the 14th annual Grammy Awards ceremonies in March 1972, Carole King became the first woman to win the “grand slam” – Record Of the Year (“It’s Too Late”), Album Of the Year and Best Female Pop Vocal (both for Tapestry), and Song Of the Year (James Taylor’s version of “You’ve Got A Friend,” for which he won Best Male Pop Vocal).

The initial issue of Tapestry long player arrived in March 1971 with little fanfare and modest expectations. A half a century later it holds a monumental place in the pantheon of pop music; a triumph of master craftsmanship married to a feminine sensibility that transformed both its audience and the marketplace.

In the 1972 recording studio conversation at A&M Records with Adler, King talked about Tapestry.

“It is typical of the magic that seems to surround that album, a magic for which I feel no personal responsibility, but just sort of happened, that I had started a needlepoint tapestry, I don’t know, a few months before we did the album, and I happened to write a song called Tapestry, not even connecting, you know, the two up in my mind. I was just thinking about some other kind of tapestry, the kind that hangs and is all woven, or something, and I wrote that song. And, you being the sharp fellow you are, (giggles), put the two together and came up with an excellent title, a whole concept for the album.”

In all, he produced six gold and platinum albums for Carole King: Tapestry, Music, Rhymes & Reasons, Fantasy, Wrap Around Joy, and Thoroughbred. Among his productions of her hits are “It’s Too Late,” “I Feel The Earth Move,” “So Far Away,” “Sweet Season,” and “Jazzman.” In 1975, he produced Really Rosie, the soundtrack to a CBS TV Special based on the Nutshell Library book series by Maurice Sendak, with words by Maurice Sendak and music by Carole King.

#

Lou Adler and Carole King in Adler’s office. (Courtesy Lou Adler Archives)

While preparing my liner notes to the 2008 2- CD reissue of Tapestry, Lou and I examined the groundbreaking album in an interview at his office.

Q: Some thoughts about Gerry Goffin who co-wrote a few tunes on Tapestry.

A: Gerry Goffin is one of the best lyricists in the last 50 years. He’s a storyteller, and his lyrics are emotional. “Natural Woman,” “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” both on Tapestry. These are perfect examples of situations, very romantic, almost a moral statement. Coming out of the 1950s, with the type of bubble gum music, and then in 1961, Gerry is writing about a girl who just might let a guy sleep with her and she wants to know, “is it just tonight or will you still love me tomorrow?” Goffin could write a female lyric. If he could write the words to “Natural Woman,” that’s a woman speaking. Gerry put those words into Carole’s mouth. He was a chemist before he was a full-time lyricist. He’s very intelligent and obviously emotional.

Q: What about Carole’s growth as a songwriter?

A: Watching her writing her own lyrics as the principal lyricist I saw her develop as a lyric writer, “You’ve Got A Friend.” A famous Carole King song. She was not confident as you can imagine then in writing lyrics, having worked with Gerry, as I’ve said, arguably one of the best lyricists over the last 50 years, maybe. But she gained her confidence within this Tapestry album and I think she had been writing a little bit, but really once we started on Tapestry, she felt confident enough to complete those songs. We went by songs. The only thing we reached back for, which was calculated in a way, which of the old Goffin and King songs that was hit should we put on this album? And, that’s how we came up with “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow.” I thought that song fit what the other songs were saying in Tapestry. A very personal lyric. Tapestry was such a partnership between Carole, myself, Hank Cicalo, the engineer, and the musicians,” stressed Adler. “So, it’s hard to say anyone suggested because we did it all together. Because it was really that kind of record.

On Carole’s demos that leads to the sound on Tapestry, her piano out front, and the bass drums, maybe a guitar, but she put in all the parts. Within her piano you could hear a string part, or hear another background part, and she did the background parts. After The City album and Writer, Carole began writing for herself.

Q: Talk to me about Carole King in 1970, before her Writer debut solo LP on your Ode Records label, and just before Tapestry began.

A: The climate of the late ‘60s had no women in the Top Ten charts, except Julie Andrews on The Sound Of Music’ soundtrack. Before the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 I flew to New York and tried to sign Laura Nyro. I invited her to perform at the festival. Carole was in a group The City, who I produced for Ode in 1968. The LP was called Now That Everything’s Been Said. The City album was supposed to be a group, even though it sounds a little like Tapestry, not so much in the subtleties, but in the way that group plays off of each other.

At the time Carole did not want to be a solo artist. She wanted to be in a group and she was more comfortable in a group. She didn’t want to tour that much or do any interviews. And we started to get those kinds of songs that would then lead us to Tapestry.

Toni Stern, a writer for Screen Gems, collaborated with Carole earlier on the Monkees’ HEAD soundtrack, Carole’s City album, and her debut album Writer. I knew her a little bit. She was introduced to Carole by Bert Schneider of Raybert Productions, producers of The Monkees. I saw her when the songs were presented with Carole to me for Tapestry.

Danny Kootch and Charlie Larkey were on The City album. They are the core certainly of Tapestry. Larkey on both electric and acoustic standup bass and his relationship with Carole at the time, husband and babies to be. And father of babies to be. His bass was very important to the sound and feel of Tapestry. As music often does, it becomes the soundtrack of the particular time.

What I think happened in ’70 or late ’70, ’71, James Taylor and Joni Mitchell and Carole, is that the listening public and the record-buying public bought into the honesty and the vulnerability of the singer-songwriter, naked in the sense — you know, what James was singing about, ‘Fire and Rain.’ Their emotions that they were laying out there allowed the people to be okay with theirs. And I think the honesty of the records, there was a certain simplicity to the singer-songwriter’s record, because they either start with vocal-guitar or piano-voice.

I really knew that it was special. It brought out emotions that no other record at least at that time had. Tapestry was really special and hit a real chord with the public.”

Q: The pre-production period was fundamental to Tapestry. Over the decades you cited the influence of jazz vocalist June Christy’s Something Cool album with arranger Pete Rugolo.

A: It’s one of the first albums that I started noticing sequence and continuity of songs and thoughts, so that it wasn’t a roller coaster emotional ride, it was a smooth ride. Musically, if there’s one other thing, Peggy Lee with George Shearing, who connected some instrument to his piano playing. He doubled the vibes, he doubled the guitar, you know? You’ll hear on Tapestry, if you go back and listen to it, I doubled a lot of Carole’s parts with Danny Kortchmar’s guitars. So, for me as a producer, those were two real influences, but especially the June Christy album. Carole’s piano playing on the demos dictated the arrangements. What I was trying to do was to re-create them in the sense of staying simple so that you could visualize the musicians that were playing the instruments.

And also tie Carole to the piano, so that you could visualize her sitting there, singing and playing the piano, so that it wasn’t ‘just the piano player,’ it was Carole. And that came from the demos, which would start with Carole playing and singing, as well as doing some of the string figures, always on piano.

During pre-production I had in my mind to use a lean, almost demo-type sound. Carole on piano playing a lot of figures with a basic rhythm section, Russ Kunkel and Joel O’Brien on drums, Charles Larkey, bass, Danny “Kootch” Kortchmar, guitar, Ralph Schuckett on the electric piano, along with David Campbell doing the string section. I also had Curtis Amy on sax and flutes, his wife Merry Clayton, and Julia Tillman. James Taylor added acoustic guitar to ‘So Far Away,’ ‘Home Again’ and ‘Way Over Yonder’ on the album. James is also on ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ and along with Joni Mitchell is one of the backing vocalists on ‘You’ve Got A Friend.’”

Q: Tell me about the initial playback of Tapestry.

A: I recall walking out of the studio after a playback with Danny Kooch, and he said, “what do you think of this?” He misinterpreted I think when I replied, “it’s the musical equivalent of Love Story,” which was a number one movie at that time. And Kootch, felt, “that’s a little soft.” What I meant was that it was an emotional album that was going to be very big and bring out emotions in people that no other record at least until that time had.

Q: Lou, the sequencing on Tapestry was crucial.

A: When I started sequencing Tapestry, I remembered and thought the sequencing on June Christy’s Something Cool was incredible, the transition from song to song just kept you in the album. It was something that I tried to accomplish with Tapestry. I took the tapes home and I went through a lot of changes. I finally fixed on the sequence and took a vacation to my house in Mexico that had a small cassette player and that’s when I came up with the final sequencing. But I went through a lot of changes.

Sequencing meant a lot in those days, the journey, or the experience or the adventure of listening to a new album and sitting down by yourself putting on that vinyl, The story that it told, the sequencing was very important. I was sequencing for the person who was listening at home, alone.

Q: The ongoing popularity and sales of Tapestry.

A: Each time from vinyl to CD to downloads. Somebody buys Tapestry again because they want to listen to Tapestry in the new mode. It just became personal to everyone who listened to it. There were enough songs in there for people to pick up this song and that song.

“So Far away’” is my favorite song. At the time of the initial release, we were still thinking AM radio as far as singles. FM radio still had an underground feel to it.

The choice of “It’s Too Late” as a single came from (A&M co-owner) Jerry Moss. The difference between Tapestry and other albums I had been involved in was the word of mouth.

On “It’s Too Late,” Curtis Amy is on sax. He had played on the Doors’ “Touch Me.” But the distinctive flavor he added to Tapestry was his flute. He hadn’t played flute in a very long time and he was nervous about it ‘cause he had just been playing sax. I said, ‘we’re gonna use flute on this.’ Curtis said, ‘Give me a couple of days to work on it.’ Curtis and (wife) Merry Clayton were both fantastic and were a very important part of Tapestry.”

##

“On Tapestry Lou and I did quite a few things,” reiterated engineer Hank Cicalo in a 2008 interview with me.

“There was a thing about the middle of Carole’s voice where it’s almost warmth with a little edge. I always wanted to capture that. I thought her piano playing was great, she would sing, and she was such a writer and performer, she knew when to lay out and when to hit it. So that was always great. Then when her vocals came when you mixed them the spaces were always in the right places. Everything was supporting her voice and that piano. That’s where the nucleus of the whole album was,” reiterated Cicalo.

“Lou was the kind of guy, as a producer first of all he had an incredible feeling for songs. He could listen to a tune and go ‘Let’s go on to the next one.’ And the way he would work it was amazing. We were mixing the album, I had some other projects going, but about the second week of mixing, we re-mixed some things, I wanted to mix some things, Lou wanted to mix some things and one night we came down, pretty much finished it, let’s listen to it from the top in one of the editing rooms in the back at A&M. Third room.

“We listened to the album Tapestry late at night. Play the whole thing down. The second engineer was there. Lights low and I said to myself ‘this sounds great!’ I don’t mean great engineering. I mean the tunes. It started hitting. I turned around to Lou, we walked out, went to the hallway, and I told Lou, ‘Something is goin’ on here.’ ‘Yeah… It’s pretty good…’ That was the first time we really struck on it. All these things, but when we sat down and listened to it then we realized it was something better than normal, a great record coming. And that’s when I felt it and I think that’s when he felt it that night.

“The writer becoming the recording artist or star seemed to be a natural path for people performing as side people. And then they made an album suddenly becoming a star or an artist or performer. And see them grow, but we were all growing the producers, the record companies. The progression was natural,” summarized Cicalo.

##

In 1972, Adler then entered the comedy world when he was introduced to Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong when they were performing in a talent hootenanny at L.A.’s Troubadour nightclub. This led to the production of five platinum Ode albums by Cheech & Chong during the ‘70s. Adler coined the phrase “hard rock comedy” to describe these recordings.

Other Ode artists included Tom Scott & the L.A. Express. Ode also released the Who’s rock opera Tommy with the London Symphony Orchestra, which featured members of the Who, Ringo Starr, Rod Stewart, Richard Harris and Steve Winwood. Ode went onto become one of the most successful “small” labels in history, grossing $30-40 million annually and starting the movement toward record produced owned “boutique” labels.

In 1973, Adler also entered theatrical stage production. It was The Rocky Horror Show, a musical, science-fiction spoof from England, first mounted on stage in Los Angeles at The Roxy, to smash results.

Adler’s involvement with films began in 1967 when he produced the award-winning feature documentary Monterey Pop, a D. A. Pennebaker film. His first non-music film was the off-beat Brewster McCloud directed by Robert Altman.

Adler’s next film production was the film version of the musical stage play, The Rocky Horror Picture Show starring Susan Sarandon, Barry Bostwick and Tim Curry. Today, nearly 50 years after its initial release, The Rocky Horror Picture Show continues to screen to this day each weekend at various pre-and-post midnight schedules in the U.S. and worldwide, and has grossed over $175 million. Rocky Horror is a sub-culture superstar and cult phenomenon, largely because of its audience participation. In 2011 a Blu-Ray DVD was released by 20th Century Fox.

In 1978, Adler made his directorial debut with his production of Cheech & Chong’s Up In Smoke. It then went on to prove that its brand of comedy could transcend time and language barriers; by now, it has brought in well over $100 million. Music is an integral part of the movie’s milieu: the youth-oriented, trend-setting Southern California pop culture.

In 1979, Adler co-produced Zoot Suit on Broadway. Zoot Suit was a major Mexican-American media project for Adler, who had desired throughout his life to pay homage to the Los Angeles Mexican-American culture in which he was raised.

Noted for his charity and philanthropy, Adler has set up scholarships at Roosevelt High School, and recently he established a music program with The Thelonious Monk Institute for the school. Adler co-founded the first rock-and-roll charity (The Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation) and directs its ongoing giving. He is on the board of directors of the Los Angeles Free Clinic in 1967. Adler is on the board of directors of the L.A. Children’s Museum and donating and built a functioning recording studio as a “hands on” exhibit.

Adler in 2011 was a feature interview subject in the Morgan Neville-directed music documentary Troubadours: The Rise of the Singer- Songwriter, and Neville’s 2013 Oscar-winning 20 Feet From Stardom.

SXSW in Austin, Texas during 2007 saluted Lou Adler on the 40th anniversary of the Monterey International Pop Festival. A Monterey celebration event was held at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood that same year.

In 2014, Ace Records, a UK-based record label issued a retrospective anthology of Lou Adler’s record production and songwriting credits, The World of Lou Adler.

In 2013, Adler was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as a recipient of the Ahmet Ertegun Award.

“If you asked me how to succeed as a record producer,” he said on being presented with his accolade by Cheech & Chong, “I’d say it helps to work with three of the best singers and songwriters: John Phillips, Carole King and Sam Cooke.”

© Harvey Kubernik 2008 and 2012

On Thursday October 5th, The GRAMMY Museum in Los Angeles is thrilled to host a special screening of director Martin Scorsese’s “THE LAST WALTZ.” The event will celebrate the 45th Anniversary of this epic music documentary that featured the farewell performance of The Band. Following the film, there will be a post-screening panel with Olivier Chastan (CEO of Iconoclast), Mark Pinkus (President of Rhino Records), and Harvey Kubernik, who attended the November 1976 event. Harvey with his brother Kenneth, authored acclaimed The Band: From Big Pink to The Last Waltz.

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. For 2024, the duo is working on a book for Insight Editions, Images That Rocked the World (The Music Photography of Ed Caraeff.)

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

On October 16, 2023, ACC Art Books Ltd is publishing The Rolling Stones: Icons. Introduction is penned by Harvey Kubernik. Spanning six decades, countless tours and album covers, this portfolio features imagery from some of the most eminent names in photography, alongside the photographers’ own memories and reflections. Includes photographs by Terry O’Neill, Gered Mankowitz, Linda McCartney, Ed Caraeff, Ken Regan, Douglas Kirkland, Dominque Tarle and founding member, bassist and photographer, Bill Wyman. Each photographer has selected images for their chapter and written an introductory text about working with the band. https://www.amazon.com/Rolling-Stones-ACC-Art-Books/dp/1788842383

Harvey Kubernik and Smokey Robinson. (Photo by Gary Strobl)

Harvey Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies. Most notably, The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Kubernik spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 Harvey appeared at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, as part of their Distinguished Speakers Series.

During 2023, Harvey Kubernik, photographer Henry Diltz and authors Eddie Fiegel, Barney Hoskyns and Chris Campion were filmed by French director France Swimberge for her Mamas & Papas documentary California Dreamin’, aired in June 2023 on the European arts television channel, Arte. Kubernik is the consultant for the film.

Kubernik was an on-screen interview subject for director Matt O’Casey in 2019 on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. He was lensed for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary on Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Bobby Womack, Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones, Regina Womack, Damon Albarn of Blur/the Gorillaz, and Antonio Vargas are spotlighted.

Kubernik served as Consulting Producer on the 2010 singer-songwriter documentary, Troubadours: Carole King/James Taylor & the Rise of the Singer-Songwriter, directed by Morgan Neville. The film was accepted at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival in the documentary category and PBS-TV broadcast the movie in their American Masters series.

Harvey was also a featured talking head in director Matthew O’Casey’s 2012 Queen at 40 documentary broadcast on BBC Television and released as a Blu-Ray DVD, Queen: Days Of Our Lives in 2014 via Eagle Rock Entertainment).