-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Alan Clayson: One Dover Soul

The release of his first new album for fifteen years presents Alan Clayson with the opportunity to write some interval notes

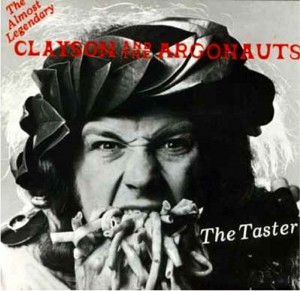

Despite the global atmosphere of worsening financial anxiety, ONE DOVER SOUL, a new Clayson long-playing gramophone record has been cast adrift on the discographical oceans. Since my debut as a recording artist in 1978—with Clayson & the Argonauts’ disinclined revival of Wild Man Fischer’s “The Taster” as a one-shot 45—my output has been, well, sporadic, particularly after a career as an author left the runway with Call Up The Groups!: The Golden Age Of British Beat 1962-67 in 1984.

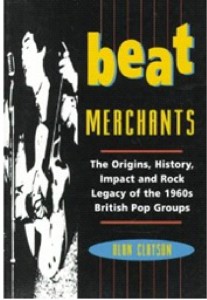

Soon I’d be scratching a living from my pen at an alarming pace. Output ranged from supermarket potboilers (some under pseudonyms) to the only English language life of Jacques Brel—which, when updated last year prompted Clayson Sings Chanson, a presentation that has been on the road ever since. Most conspicuously, there’s been the Backbeat film tie-in, Beat Merchants (a more extensive history of the British beat boom), authorised histories of the Yardbirds and the Troggs, and Death Discs, also the subject of a programme I scripted and presented on national radio. Moreover, I not so much dipped a toe as plunged headfirst into many other—often unexpected—musical waters, such as a 2002 tome about Edgard Varèse, Frank Zappa’s boyhood hero, and the missing link between Stravinsky and John Cage.

Thus my chief source of income came via what I wanted to do second best after my adolescent imagination had been captured by the allure of pop stardom back in nineteen-sixty-forget-about-it.

That’s why if presented with a choice between a run of blockbusting biographies or merely getting by as an entertainer, the roar of the greasepaint would win every time, despite the countless occasions I’ve all but quit the business forever when, to quote from Tony Hancock’s suicide note, “things seemed to go wrong too many times.” This was instanced by an engagement in High Wycombe one April evening in 1985—for which I’d dashed from a record date notable for constant retakes of a minor guitar part. At home, the immersion heater hadn’t been switched on, necessitating a chilly shampoo. I also swilled down an evil if energizing concoction of six raw eggs beaten up in a glass of Guinness as I waited for an overloaded van exactly one hour late. The janitor answered our banging but did not help lug careworn equipment into a darkened upstairs cavern with its echo of alcohol, tobacco and food intake from that afternoon’s wedding reception.

Following a harrowing soundcheck, we busied itself in bar and dressing room until showtime before an audience of twelve (including the support act). Small too was the percentage of the gate as there’d been a freak cold spell with heavy rain all day. There was also something good on the TV and the local newspaper was on strike, thus precluding advertising. Next morning, I received an agitated call from our road manager to say four borrowed microphones had been stolen.

This incident took place shortly before Clayson & the Argonauts—our very name now a millstone round our necks—made a seemingly final public appearance, opening for the Nashville Teens. By then, we were like a soldier fatally wounded that keeps fighting, not knowing how critical the injury is. To all intents and purposes, we’d been over for ages, a faded memory, a tattered newspaper clipping. So we scattered like vermin disturbed in a granary. All that remained was the sound of our aural junk-sculptures as a spooky drift from the shadows in some lonely back-of-beyond palais, maybe one refurbishment from demolition. Yet there’d been moments when…

Certainly, the wheels of the universe had been rolling in our direction as the watershed year of 1977 loomed. Suddenly, there was some kind of future with none of the leitmotifs of tragedy or farce that had blighted the previous two years. We had, for example, been hustled out of one night spot at gunpoint; the drummer had been gaoled for eighteen months, and two other personnel quit; one fated to co-produce Arthur Mullard and Hilda Baker’s hit duet of “You’re The One That I Want”; the other to father one of Girls Aloud.

Yet I muddled on, and Clayson & the Argonauts made a London debut at the 100 Club (with the then-unsigned Jam and Stripjack, led by Lee Jackson, formerly of the Nice) on 9 January 1977. Next up was a full-page Melody Maker spread, courtesy of its enthralled future editor Allan Jones, and me being spoken of and written about in the same sentences as the likes of Tom Robinson, John Otway, Elvis Costello—and ‘Wreckless’ Eric Goulden.

During the resulting three years of expecting to be on Top Of The Pops next week, a sweep of events embraced more dates than could possibly be kept; a BBC Radio One In Concert, and headlining at the Marquee, back at the 100 Club, Amsterdam’s Melkweg and venues of similar standing round Europe—always, it seemed, one week after Wreckless Eric and one week ahead of the Adverts—as well as any number of university hops such as that in Belfast at the height of the Troubles where an audience was still demanding more after six encores. In parenthesis, among those second-billed to us somewhere in the Midlands were what became the Eurythmics.

En route, we were central to the wreckage of a Luton auditorium; a near-lynching at Barbarella’s in Birmingham; a punch-up and car chase after a midnight matinee in Canning Town; a season in Amsterdam’s red-light district (our ‘Hamburg’ period); some woman jumping onto the boards to tear off all her clothes at Islington’s Hope and Anchor, and a bloke doing the same during almost-but-not-quite a riot at the Granary in Bristol. Soon, we were past resistance to circumstances that made it impossible to go back to get up-get to work-get home-get to bed groundhog days. If the van had drawn up outside a ballroom on Pluto, it mightn’t have seemed that odd.

Delivering “more than a performance, an experience” (Sounds), Clayson & the Argonauts were, therefore, a very ‘happening’—and hard-working—group. Somehow, we made time to record “The Taster,” a three-minute waste of time that started as merely part of a medley. We came to loathe it so heartily that we dropped our approximation of it from the set unless it was specifically requested – which it never was. Nevertheless, Virgin Records had been convinced that “The Taster” was chartbound, and we spent an overcast day at London’s Psarm Studio—where Queen made “Bohemian Rhapsody”—trying to hack a single from a lump of solid acetate. After a blaze and subsequent fire brigade ministrations damaged the master tape, it crossed my mind to stir up a rebellion against “The Taster” and everything else I perceived was desecrating my self-picture as an artist and the Argonauts’ now thoroughly road-drilled musicianship. Yet, in the death—and in another expensive complex, Regent Sound—we were too unsure of ourselves for open mutiny when, say, Hugh Murphy, the producer foisted upon us—fresh from a smash with Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street”—replaced our keyboard player’s triplets with those of Tommy Eyre, formerly of both Dave Berry’s Cruisers and Joe Cocker’s Grease Band, and destined then to be Wham!’s musical director.

“The Taster,” however, was a domestic ‘turntable hit’ and—proving some sort of point as far as I was concerned—its self-penned B-side, “Landwaster,” an excerpt from a then-unreleased in-concert LP, was a fleeting Top Twenty entry in Belgium after a radio presenter in the Netherlands started spinning it by mistake. Nonetheless, its ultimate descent into the bargain bin was a prelude to my ‘wilderness years’.

For a while, it’d been business-as-usual until we couldn’t be bruited on posters as “Virgin Recording Artistes” anymore, as the label, smelling a perishable commodity, didn’t take up its option on further releases. It was all over too with Hugh Murphy—who’d grinned cheerfully and waved us farewell as we drove away from Regent Sound, but who—as we learnt later—had slagged us off (with particular reference to me) for our “unprofessional” behavior—though Clayson &the Argonauts’ saga was to climax with 1985’s valedictory What A Difference A Decade Made album earning rave reviews in both Folk Roots (!) and The Observer.

As this door closed, so opened one that awoke a literary calling dormant since my teenage contributions to the notorious Schoolkids Oz in 1970. A Record Collector article about the Dave Clark Five had come about after I’d bumped into their ex-bass guitarist in a Camberwell music shop. More articles followed—and then came Call Up The Groups!.

A spin-off from 1995’s Beat Merchants was a tie-in ‘various artists’ album that kicked off with “The Man Of The Moment” (which rhymes “Nashville Teens” with “Swinging Blue Jeans”) by Clayson and an ad-hoc Argonauts. Beat Merchants also contained Dave Berry’s “The Moonlight Skater,” which I composed with Jim McCarty, drummer and co-writer (“Still I’m Sad,” “Shapes Of Things” et al) with the Yardbirds. As a nascent version had turned up on Raindreaming by Stairway (with vocals by Jane Relf, ex-Renaissance), Jim and fellow Stairway-farers, Clifford White (a New Age colossus) and Louis Cennamo (ex-Renaissance) were roped in for the Berry session. In parenthesis, with its spellbinding melody and evocative lyrics, “The Moonlight Skater” satisfies every qualification of nothing less than a Christmas Number One, but, to paraphrase Mandy Rice-Davies, I would say that, wouldn’t I?

This was one of many cultural diversions towards the turn of the century as I was also overseeing the records of others, beginning with an EP by Welwyn Garden City’s boss combo, the Astronauts. More far-reaching, however, had been Dave Berry’s ‘cover’ of a Clayson opus, “On The Waterfront” from What A Difference A Decade Made. Later, I graduated from starstruck fan to supervising and composing the lion’s share of Dave’s output on disc since 1996’s Hostage To The Beat album—and was recruited into his backing Cruisers. “Alan remains the most unique musician I have ever employed,” reckoned Dave, “and it was entirely through him that my recording career revived in the late 1980s.”

Because of him and Call Up The Groups!, I became something of a ‘face’ on the Sounds Of The Sixties circuit, and such networking paid off when I was enlisted to hammer keyboards as one of Screaming Lord Sutch’s Savages, and undertake a string of solo one-nighters in the north-east with Denny Laine, and, before that, a stint as musical director and bass player for Twinkle during her brief stage comeback in the mid-1990s. I functioned too as chief show-off in duos with accompanists of the calibre of Wreckless Eric and Dick Taylor of the Pretty Things—who likened bookings with me to “running downstairs at full speed without a handrail.”

Then a telephone call in June 2005 exhumed what I’d imagined was buried forever. That Christmas, Sunset On A Legend, a double-CD retrospective by Clayson & the Argonauts was released by a London record company—and twenty years after what was thought to be the last hurrah, the group was up-and-running again after, ostensibly, a one-off show at an ultra-trendy West End venue, attended by devotees from as far away as France, Holland Scotland and the USA. Moreover, the proceedings were filmed for release on the DVD, Aetheria: Alan Clayson & The Argonauts In Concert—and, immediately after the dust settled, we were approached for further ‘farewell performances’ as a ‘tribute band’ to ourselves.

I’d been widening my work spectrum too with a solo act that now defies succinct description. This extended to prestigious supports to such as the Yardbirds at the Marquee; emerging as the Surprise Hit at this or that back-of-beyond festival; two appearances in Newcastle that drew what the promoter described as “extreme audience reaction,” and four visits to the States—ostensibly to plug books. Expecting a dry, writer-ish lecture, those at this convention hall or that exposition centre could hardly believe I was real as I plunged into onstage excesses that occurred in the knowledge that I was unlikely to see any of these folk again—or was I?

Within days of shaking off jet-lag back the first time in 1992, a package came from two ladies who’d been among those flocking round him like friendly if over-attentive wolfhounds after a soirée in Chicago, and who had each bought a What A Difference A Decade Made. As well as a long letter, they’d sent a sweatshirt with my image and the words CLAYSONFEST ’92 on the front. Apparently, I now had a North American fan club.

Twenty years later, the few remaining members were twitchy with anticipation throughout the weeks leading up to the issue of ONE DOVER SOUL on producer Wreckless Eric’s Southern Domestic label, and containing twelve Clayson originals and an overhaul of “Un Grand Sommeil Noir”—verse by French symbolist poet Paul Verlaine set to music by Edgard Varèse.

Every note was hand-tooled in Eric’s studio in Norwich and—principally—when it was reassembled after he moved to a village near Limoges in south-west France with his North American wife Amy Rigby, a singer-songwriter of similar artistic appetite. Transported there too was an Aladdin’s cave of instruments, ranging from the newest-fangled synthesiser to the wheezy old harmonium I’d pressed when, with Eric at the controls, we’d recorded 1999’s “The Last Show On Earth,” a ballad concerning the aftershock of Screaming Lord Sutch’s suicide.

Because we’d led parallel lives during the sweep of events consequent to us each occupying “a premier position on rock’s Lunatic Fringe” (Melody Maker again) way back when, Eric and I hadn’t actually met until the late 1980s when his music came to encompass ‘techno, rave, jazz, drum machines, samplers, and I started having fun marrying it up with other things I like—trash rock ‘n’ roll, funk, soul, R&B, bubblegum, psychedelia… You get older and, if you can be bothered to look for it, there’s even more fun to be had.”

Indeed, there is. As night thickened on the June day in 2008 after he picked me up from Limoges airport, a sonic adventure began in which two deeply middle aged men behaved at times like unrestrained children in a toy shop. The following morning, eyes parted on a region swimming with humidity, but the studio’s double-glazing stayed shut against the infiltration of noise both ways as Eric and I layered flesh onto the skeletons of four items for what would become ONE DOVER SOUL.

As the week unfolded, everyday life ground to a standstill apart from us trying to stick doggedly to the demarcation line between producer and client. Having been on the other side of the fence, I understood the necessity of taking direction from one who had already apportioned trackage, short-listed devices and effects, and visualised each track’s overall ‘shape’. Crucially, our personal dynamic was such that utterances unamusing to anyone else might have us howling with laughter on the carpet.

So far, so amiable. It was foreseeable, however, that I’d be bathed in tedium during this or that slow mechanical procedure, and Eric might have bitten back irritation at some of my back-seat-driver-ish suggestions. Nonetheless, off the assembly-line without fuss poured another three tracks, one augmented by Amy cooing like a sweetly bestial Emmylou Harris. In the teeth of the weather, we were still firing on all cylinders on the day before my departure—as instanced by “Heedless Child,” a Clayson-Goulden opus sturdy enough to warrant a rough mix to which we listened on a car stereo with the moon shining over slumbering woodlands.

In January 2010, I breezed into the studio as if my direct involvement with the album hadn’t been on ice for eighteen months. “Ice” is a crucial word here as Eric and Amy’s heating system had just exploded, prefacing Arctic conditions that prevailed until Tuesday.

The cold kept us alert as we began by reviewing Eric’s continued work on ONE DOVER SOUL from my dodgy demos. He’d also improved upon what had been done already—for example, by wheeling in Ian Button from Death In Vegas to splatter drums here and there.

When afternoon became evening, I’d fingered a stately mellotron linked to a Vox Continental, and was harmonising with my own lead vocal on autobiographical “The Old Dover Road” to Eric’s satisfaction –and my own by the time I lay as rigid as a crusader on a tomb.

Distressing details why aren’t necessary, but my singing of “I Hear Voices,” an opus in and out of Clayson recitals for the past four years, was honed to razor-sharp piquancy. Over the next four days too, I overdubbed mellotron to backing hinged on an auto-rhythm from an electric piano I’d found in a skip fifteen years before. Via means peculiar to himself, Eric had isolated this from the demo—as he did a quasi-military beat from an ancient Farfisa organ as the bedrock of “The Refugees,” started from scratch, and embracing a piano solo that wedded the salient idiosyncrasies of Russ Conway and Cecil Taylor after overall outcome shone through with appositely sepia-tinged clarity.

Driving home after my return flight from Limoges, I couldn’t resist an earful of work-in-progress, and concluding that Eric Goulden had drawn from me the best I could give. For that reason alone, if ONE DOVER SOUL has the commercial impact of a tract from the Flat Earth Society, well, so what?

For further information about Alan Clayson and ONE DOVER SOUL, please investigate www.alanclayson.com