-

Featured News

The MC5: A Eulogy

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack—

By Doug Sheppard

And then there were none. Five equals zero. The morning of May 9, 2024, the last surviving member of the MC5, drummer Dennis Thompson, died while recovering from a heart attack— -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

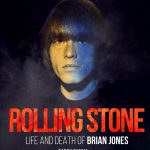

Rolling Stone: Life and Death of Brian Jones

Documentary review by David Holzer

There’s a painful moment in Danny Garcia’s Rolling Stone: Life and Death of Brian Jones that captures the raw tragedy of Brian’s stumbling downward spiral of a life.

It’s December 1967 and Brian has just left the Court of Appeal in London after one of his drug busts. Trapped by a horde of reporters, assaulted by camera flashlights, his face is bloated and blank, his hair is unkempt, his insolent satyrical beauty gone. He wears a thick sheepskin Afghan jacket.

Slowed down by Garcia to chilling, darkly poetic effect, the black and white clip shows Brian as a dazed sacrificial lamb waiting for slaughter.

Garcia’s movie is so compelling precisely because it considers all the factors that drove Brian to this point and on to his tragic end without imposing a single, limiting definition. He also gives equal weight to different interpretations of the story of how Lewis Brian Hopkins Jones became Brian Jones, briefly golden rock god.

This is one of the great strengths of the movie: it has real depth. Garcia’s subjects in previous movies have included Johnny Thunders, Sid Vicious and Stiv Bators who all lived out a cartoonish rock star fantasy shaped partly by Brian’s example as taught to Keith Richards.

As veteran British music journalist Chris Salewicz says towards the end of the movie, Brian had an “aura of dissolute hedonism [and is] the first example of any British rock star living the rock and roll lifestyle…maybe that’s a salutary warning as well.”

Garcia’s movie is also excellent on what intrigues many of us about Brian. He was far more than just a “British rock star.”

Time and time again, the people Garcia interviews emphasize just how “ahead of the curve” Brian was, as his friend Prince Stash Klossowski says.

Prince Stash is a joy. His eccentric appearance—hair in what looks like a single iron-grey dreadlock coiled around his head and held in place with a bandanna—and languid aristocratic drawl are a fabulously entertaining contrast to his no-bullshit take on Brian’s story.

Being able to hear and see characters whose names are familiar from the various books about Brian is another of the great pleasures of Rolling Stone: Life and Death of Brian Jones.

Among these are Richard Hattrell, the childhood pal so cruelly tortured by Brian in London, Dick Taylor and Phil May of contemporaries the Pretty Things and French actress/model Zouzou.

This more than compensates for the absence of any interviews with members of the Stones, although we do hear sixth Stone Ian Stewart’s voice. By now, we’ve become so familiar with Mick and Keith on the subject of Brian it’s hard to imagine their presence would have added anything to Garcia’s movie. Unless they came clean.

Garcia also makes powerful use of archive film of Brian, including home movie footage of him aged 17 sailing down the Worcester & Birmingham Canal in the UK with his girlfriend Valerie Corbett.

Brian’s in great shape but his eyes suggest his life of “dissolute hedonism” had already begun.

Hearing some of Brian’s music, especially critiqued by someone knowledgeable, would have certainly added another dimension to the movie. It’s a shame that Brian’s soundtrack for Volker Schlöndorff’s 1967 movie A Degree of Murder starring Anita Pallenberg can only be heard on a fragmented bootleg.

There’s a snippet of Joujouka music in Garcia’s movie but, since it accompanies a clip from the daft 2005 Brian biopic Stoned, it’s not clear whether it comes from the groundbreaking 1971 album Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka.

Instead, we have a soundtrack featuring, among others, Dick Taylor, the Alabama 3 and Greg Stackhouse Provost, formerly of the Chesterfield Kings and a contributor to this magazine, and guitarist/writer John Perry. Perry’s acoustic and slide “Brian” is the standout for me.

If I have a criticism, it’s that around half the movie is given over to exploring the conspiracy theories around Brian’s death at his East Sussex home Cotchford Farm on July 2, 1969.

I would have preferred that some of this time had been given over to celebrating Brian’s achievements as a supremely gifted musical pioneer and sartorial innovator.

Rolling Stone Life and Death of Brian Jones is out now on DVD in a package that includes the film poster, deleted scenes, bonus footage, an extra featurette and the trailer. The movie will be streamed on a number of platforms including Amazon. The soundtrack is available on vinyl. Find out more at www.chipbakerfilms.com.

David Holzer is writing a book about the legendary Master Musicians of Joujouka who Brian recorded in July 1968.

What’s Missing in Music Bios? Often What’s Great About the Music

By Bill Wasserzieher

The problem with many documentaries about solo artists and/or bands is that they “print the legend,” to lift that old line from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. That is, filmmakers, being storytellers, flesh out the accepted version of their subject’s career—and that’s good for what it is, overviews being useful for the uninitiated—but rarely do they dive deep for what is at the core of the actual art.

To put it another way, is there even one among the scores of Dylan documentaries that digs into his songwriting process? I’d love for the hire-by-the-hour “talking heads” who pop up in them to focus on the creative vision that, for example, produced “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.” Think about those opening lines:

When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez and it’s Easter-time too, And your gravity fails and negativity don’t pull you through, Don’t put on any airs when you’re down on Rue Morgue Avenue, They got some hungry women and they’ll really make a mess out of you.These are maybe the bleakest lines since T.S. Eliot was ruminating on “The Hollow Men” and “The Wasteland.” But, no, we always hear about young Bob scuffling in the Village, courting Joan Baez, going electric, retreating to Woodstock, finding/losing/finding religion, ad infinitum. Instead, tell me about those carbolic lines and how his etched-with-acid voice shoves them to the gut.

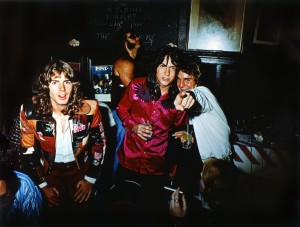

Jody Stephens, Andy Hummel and Alex Chilton. (Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures. Photo credit: William Eggleston, Eggleston Artistic Trust)

This problem comes to mind with the new and very competently made documentary Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me (Magnolia Pictures). The filmmakers present nearly a two-hour overview of a band whose members were young white guys from Memphis—one a former teenage hit-maker with the Box Tops—who cut an indisputably great album, #1 Record, that went unnoticed; followed by another, Radio City, nearly as good and equally ignored; and then a third, Sister Lovers, which was never actually finished, as the players drifted off to different and mostly sad, bad fates.

The filmmakers get the Big Star story from the band drummer Jody Stephens and bassist Andy Hummel, from friends and relatives of deceased members Chris Bell and Alex Chilton, their Ardent recording studio associates (Ardent headman John Fry is the film’s executive producer), an array of rock critics (including a funky old Lester Bangs clip), plus numerous praise-wielding musicians, among them Jim Dickinson, Chris Stamey, Mike Mills, Robyn Hitchcock and Ken Stringfellow.

No denying it’s a well-crafted overview, but what’s missing is serious analysis of the songs and the musicianship on No. 1 Record. What are those songs about? What do say about life as Chris Bell and Alex Chilton were experiencing it, their individual and sometimes at war psyches (Bell bipolar and troubled by sexual identity issues, Chilton bitter, caustic, frequently loaded), and how did their minds and voices work together and separately? These are things crucial to the Big Star story. Otherwise the band was just one of millions that arguably could have been the new Beatles but were not, though at least this one became famous after the fact and served as a fountainhead for power-pop bands that came later.

Plus the documentary, while keeping with the legend, plays it cautious. Nowhere is the Alex Chilton I met a few times, first in New York City during the late 1970s when he had a loose ensemble called the Cossacks. One night I asked him about the Big Star records, and he responded, “Fuck that old shit.” Nearly 25 years later, after he and Jody Stephens reformed Big Star with members of The Posies, I cornered him after a solo show at McCabe’s in Santa Monica, where he had intentionally bummed out a capacity crowd hoping to hear a few Big Star and/or Box Tops tunes by playing instead “Volare” (“Nel blu dip into di blu”) and other songs better suited to a Dean Martin tribute. I asked him why, and he said, “I hate my fans.” Sometimes an artist is his own worst enemy, but Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me doesn’t say so.

And that brings to mind those purveyors of commercial/corporate rock, the Eagles. At least the documentary History of the Eagles manages to do more than provide the standard career recap. Glenn Frey, the film’s executive producer and primary talking head, spends three hours trashing everyone who has ever rubbed him wrong—producer Glyn Johns who got the Eagles their first hits, former bandmates Bernie Leadon and Randy Meisner (whose previous stints in Dillard & Clark, the Flying Burrito Bros. and Poco gave the Eagles early credibility), original manager and label boss David Geffen, even Timothy B. Schmit and Joe Walsh who are still contracted sidemen in the band, and especially Don Felder who is reduced to tears when interviewed on how he came to be kicked out.

According to Frey, only he and Don Henley really matter in the grand scheme of things—and that’s why he’s proud to say they get bigger bucks than the others, money apparently his ultimate gauge for success. At no time does Frey ever seem to see beyond his own ego, coming off as vengeful, arrogant and self-absorbed. It’s fascinating and twisted, as creepy as watching footage of performance artist Chris Burden nail himself to the hood of a VW Beatle. But at least it’s more than just another example of “print the legend,” and we do learn something about his band’s songcraft, including that Frey dreamed up the title “Life in the Fast Lane” while roaring through Hollywood at 90 mph in a Corvette driven by his dope dealer on their way to a poker game.

In issue #36 of Ugly Things, Alan Bisbort has a review of a DVD titled A Band Called Death. Comprised of three African-American brothers from Detroit who played rock rather than Motown, the band was good enough for Clive Davis, then the head of Columbia Records, to offer to sign them if they would change their name to something less of a sales-killer than Death. But they wouldn’t, so he didn’t. Now that’s a legend new for the telling. Also, for a more detailed review of Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, see Jon Kanis’ piece in the same new issue.