-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers -

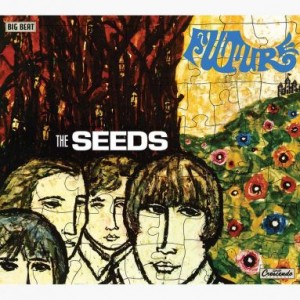

Sky’s Limits: The Seeds Stumble Into Psychedelia

By Doug Sheppard

To capitalize on their hit single and to keep up with their contemporaries, the Seeds entered the sessions for their third album with aspirations of a more sophisticated sound. It was a great plan, but two things stood in the way: their own limitations and the overconfidence of leader/vocalist Sky Saxon.

Saxon’s inflated sense of self-importance only complicated the band’s limits, but 1967’s resulting Future album came off more as a mixed bag than an embarrassment. Between an overdubbed tuba on “Two Fingers Pointing on You” and “March of the Flower Children” (with Sky’s inane spoken-word intro) and weak material like “Painted Doll” (crappy ballad) and “Where Is the Entrance Way to Play” (forced profundity), Future has its share of awkward moments. The overdubbed harp may be added to that list, but not on “Flower Lady and Her Assistant” — a darker textured number where the objective doesn’t seem as unrealistic — and the obligatory long track “Fallin’ ,” where an “Evil Hoodoo” vibe portends a bad trip. The resurrected B-side “Out of the Question” and “Pushin’ Too Hard” soundalike “A Thousand Shadows” are the best of the lot — probably because they’re the only two that recall the Seeds’ original sound.

Ironically, three of the best tracks from the session — “Chocolate River,” “Sad and Alone” and “The Wind Blows Your Hair” — were left off the album, but appear (plus alternate versions) here. “Rides Too Long” — the original version of “A Thousand Shadows” under a different title — is another highlight of this expanded edition, as are early versions of “Gypsy Plays His Drums” and “Satisfy You,” not to mention less adorned versions (the mono “Travel With Your Mind” is the best mix) of a few album tracks. On paper, the full-length version of “900 Million People Daily All Making Love” has the potential to be another — but 10 minutes of it is a tad too much, and some of these songs (see previous paragraph) will never sound good, no matter what the mix.

Velvet Underground – Golden Archive Series (Sundazed) LP/CD

The Velvets’ entry into the Golden Archive Series that MGM ran for a mere 12 months starting in 1970 is a curious one. A series more known for packages filled with quantifiable hits by name pop, country, and jazz artists was a strange place for perhaps—along with the Mothers of Invention (also, oddly, profiled in the series)—the most idiosyncratic combo on their roster at the time. In 1970 most people hadn’t wrapped their heads around the Velvets—though, their immediate influence was starting to swell in pockets around the globe—and their label clearly understood them no better. Was MGM attempting to re-package both groups for the pop marketplace?

Oddly sequenced, the set reads like either suits determining the most radio-friendly tracks from their first three LPs, or same enlisting a common-man intern not familiar with the group to choose their most palatable sides, with the brutality excised from their grand blend of beauty and brutality. Yet “Heroin” and “White Light/White Heat” are strangely tossed in the mix throwing things askew. You can’t fault the tracks chosen, as they’re all catalog classics, though focusing on the more spiritually searching, and messy love elements, with a side-order of chemical struggles and darker edges. However, some minor sequence tweaks—either for flow, or to create a narrative out of shifting perspectives—would’ve bolstered the impact of the set greatly upon initial release. From a fiscal POV I understand, but it’s an absolute shame so little of their ’67-’68 material is represented—three tracks from The Velvet Underground & Nico, two from White Light/White Heat, and the other five from their recent, decidedly more pop-slanted 1969 S/T album.

Opening with a triple-play of hushed brilliance concerning internal struggles of existence and coupling (“Candy Says, “Sunday Morning,” and “Femme Fatale”) grabs the ears firmly, but a sharp shift to the pulsing, in-the-red, abrasive noise-fest “White Light/White Heat,” is too forceful a move. Their thuggish simplicity and vocal drone is represented in “Here She Comes Now,” and too the sweet Tin Pan Alley pop side with Moe at the mic on “After Hours.” On the whole a good variety is displayed. While there’s a marked step from the total aural and moral destruction of their earlier sides beloved by rock’n’roll trufans, VU were never really something you could easily place in a ‘commercial’ box even during their attempts at sweetness—there was always one finger raised in your peripheral.

All in all, this is a good entryway into the wonder of VU sans all the dangerous tangles and barbs, but with some retrospective knowledge perhaps a CD is the choice here so you can create your own ultimate playlist. (Jeremy Cargill)

The Radiators From Space Story, Part 3: Troubled Pilgrims

By Brian Neavyn

The arrival of the Radiators From Space on the Dublin scene as punk emerged was followed in early 1977 by their super-charged debut single “Television Screen.” Their move to London that autumn without lead singer Steve Rapid coincided with the release of their red hot album TV Tube Heart. On this evidence the band were very much a contributor to the new punk rock sound. This early period and the band’s interaction with the London punk scene is covered in detail in UT#35. Linking up with producer Tony Visconti as the year ended, opened up possibilities for songwriters Philip Chevron and Pete Holidai. They grasped the opportunity to pursue a musical path that their earlier pre-punk music influences determined. In early 1978, the Radiators (re-named) launched their radical new sound. The powerful and catchy glam-pop single “Million Dollar Hero” very nearly broke into the charts and was the appetizer for their unique Ghostown album, which was recorded in summer 1978.

However the punk scene was changing and developing so rapidly month by month that all acts associated with the early ‘76/’77 scene faced an uncertain reception. For the Radiators, much of their punk fanbase had peeled away by the time Ghostown was released over a year later. The delayed release did not help their cause and the band broke up in early 1981. Despite two project-focused but brief activities in the late 1980s the Radiators from Space were no more. UT#36 carries the story of the Ghostown album. The album’s literary references were woven with criticism of the state and in particular the church. This story also covers the release in 1989 of the single “Under Clery’s Clock” where Phil Chevron, in revealing his homosexuality, wrote of the dating experience of a young gay man.

Throughout the ‘90s their musical legacy attracted an ever growing international interest. The Radiators From Space reformed in late 2003 to play a Joe Strummer tribute concert. Guitarists Phil Chevron and Pete Holidai were joined for the show by original singer Steve Rapid and a new rhythm section of Cait O’Riordan on bass and Gareth Averill (Steve’s son) on drums.