-

Featured News

Shel Talmy: August 11, 1937 – November 14, 2024

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

UNO MUNDO (It Came From East Los Angeles)

By Harvey Kubernik

Dedicated to Mamie Van Doren Con Art Aragon

This spring and summer at select movie theaters and on cable television’s Spectrum SportsNet, filmmaker Stephen DeBro in his sports and music documentary 18th & Grand: The Olympic Auditorium, tells the story of Los Angeles through the distinctive voices of boxers, wrestlers, roller derby skaters and rock musicians who performed at the Olympic Auditorium. The venue opened in 1925.

In 1951, rhythm & blues concerts were held on the premises. During the 1969-1970 period, Little Richard, Frank Zappa, Mountain, Jack Bruce and Ten Years After were on the marquee. In the eighties and nineties, Public Image Ltd debuted there, and soon afterwards, monthly concerts were promoted by Gary Tovar and Goldenvoice Productions headlining Dead Kennedys, the Dickies, the Circle Jerks, Bad Religion, Suicidal Tendencies, and X. Music videos for Bon Jovi, Kiss, Air Supply, Janet Jackson, and Rage Against the Machine were produced in the landmark location at the corner of 18th Street and Grand Avenue, just south of the Santa Monica Freeway in downtown L.A.

“From the beginning the Olympic was an extension of Hollywood’s back lot,” underscores DeBro. “So many great films were shot at the Olympic, starting with Buster Keaton’s Battling Butler, The Three Stooges Punch Drunks, The Manchurian Candidate, Raging Bull, the Rocky series, Million Dollar Baby, The Turning Point, Requiem for a Heavyweight, The Sting II, and in 2003, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle. There were hundreds of TV shows and commercials.”

It’s now the Korean-American Glory Church of Jesus Christ.

The 18th & Grand: The Olympic Auditorium soundtrack is by War, Shuggie Otis, Charles Wright & the Watts 103rd Street Band, Queens of the Stone Age, Dead Kennedys, the Weirdos, Cannibal & the Headhunters, Quetzal and Jungle Fire (Albert Lopez).

DeBro, author and music/culture historian, Gene Aguilera, along with LA Plaza de Cultura’s Karen Crews Hendon and Esperanza Sanchez, are serving as curators of the museum’s forthcoming August 11, 2023-May 12, 2024, 18th & Grand: The Olympic Auditorium exhibition recounts the 80-year history (1925-2005) of the Olympic Auditorium, the home for visceral entertainment in Los Angeles with artifacts from all facets of the venue’s storied history. The exhibit will be held at La Plaza de Cultura Y Artes Museum, 501 N. Main Street, Los Angeles, California 90012.

18th & Grand: The Olympic Auditorium reminds us about nearby East Los Angeles and adjacent Boyle Heights, east of the Los Angeles River. These two Los Angeles’ Chicano/Mexican-American communities gave us Top Forty music hitmakers, Verve Records’ founder Norman Granz, record producers and songwriters Herb Alpert, Lou Adler, H.B. Barnum, Mike Stoller, as well as musician/deejay Lionel “Chico” Sesma, Black Eyed Peas’ will.i.am, and Gene Aguilera.

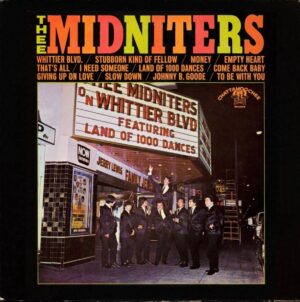

Thee Midniters also hail from this vibrant region, who had a monumental instrumental anthem with “Whittier Blvd” in 1965. The Latino group’s recordings and live shows were initially championed by Southern California AM radio deejays Art Laboe, Dick “Huggy Boy” Hugg, Godfrey Kerr, Casey Kasem, Sam Riddle, Dave Hull and “the Real” Don Steele. Wolfman Jack in Chula Vista, California programmed their expeditions on border radio station XERB with 50,000 watts of soul power!

Thee Midniters’ “Jump, Jive & Harmonize” appears on the Rhino Records box set Where the Action Is! Los Angeles Nuggets 1965-1968. The Premiers, another East Los Angeles group, are also heard in this collection with “Get On This Plane.”

Los Lobos’ rendition of Thee Midniters “Love Special Delivery” from their Native Sons won them a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Americana Album.

Additional Chicano recording artists from East Los Angeles were on national AM radio playlists. The Premiers had a hit record in 1964 on the Faro Records label with a cover of Don Harris & Dewey Terry’s “Farmer John,” later cut by Neil Young and Los Lobos.

During 1965, Cannibal & the Headhunters were on the charts on the Rampart Records label with their version of American R&B singer Chris Kenner’s “Land of a Thousand Dances.” The tune has been waxed by Fats Domino, Major Lance, Rufus Thomas, Johnny Rivers, the Walker Brothers, the Alan Price Set, Geno Washington & the Ram Jam Band, Little Richard, the Young Rascals, Ike & Tina Turner, Steve Cropper, and Patti Smith. Jimi Hendrix in his stint backing Curtis Knight played the number nightly in New York City at The Cheetah club.

In 1965, Cannibal & the Headhunters were the opening act on the Beatles’ second American tour, and backed up by the King Curtis band.

This decade, scant media attention and documentation exists on the East Los Angeles groups and record producers who created sonic gifts to our ears.

(Poster courtesy Mark Guerrero.)

##

In 2014, I interviewed deejay and Original Sound Record label owner Art Laboe. His bio-regional link to the records emanating from East L.A. coupled with his keen sense of understanding his audiences’ tastes for national R&B, soul, and pop hits deserving additional retail exposure, resulted in 1958’s compilation album, Oldies But Goodies Vol. 1. It stayed on Billboard’s Top 100 chart for 183 weeks.

Over two dozen follow up Oldies But Goodies volumes also made the charts into 1965. Laboe birthed an industry that persists to this day: repackaging older recordings into new collections. There are now multiple Oldies But Goodies albums available on compact discs.

“In the late fifties the Latinos were heavy at that time at El Monte Legion Stadium—that’s where they all lived,” explained Laboe. “That’s where the Latino thing came in with Art Laboe and that connection. I would play ‘A Casual Look’ from Trudy Williams & the Sixteens, ‘Earth Angel’ by the Penguins (which Dootsie Williams gave me), and Rosie & the Originals’ ‘Angel Baby.’ Original Sound would later release the Penguins’ ‘Memories of El Monte.’”

Laboe was the very first DJ to spin West Coast rock ’n’ roll, to merge race music under one broadcast. When Elvis Presley came to town in 1956 with manager Colonel Parker, their only interview granted was to Laboe. Art had been the first person to play the Sun Records of Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. He introduced Ricky Nelson to the radio airwaves. Laboe initiated the concept of “song dedications,” the intimate dialogue relationship with Art and his devoted listeners over a 70-year career.

In the October 14, 2022 issue of The Guardian, writer Richard Williams in his obituary praised Art Laboe’s multi-cultural achievements.

“His other great distinction was the creation of a series of concerts at the El Monte Legion Stadium, a venue built as a sports centre for schools. Laboe knew that Los Angeles’s city fathers, unnerved by the arrival of rock’n’roll and by the prospect of black, white and Hispanic teenagers mingling together in large numbers, had banned public dances for under-18s. The town of El Monte, however, was outside the LA city limits and subject to no such restriction. Beginning in 1955, and for the next six years, Laboe presented dances at the 3,000-capacity stadium, featuring such hit artists as Jackie Wilson, Ritchie Valens, Sam Cooke and Ricky Nelson, as well as the doo-wop groups particularly beloved by the young Chicanos and Chicanas among his multiracial audience.”

In 2014 I spoke with several musical mainstays of the East Los Angeles world for my book Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972: Little Willie G of Thee Midniters, author/boxing scholar Gene Aguilera, musician and East Los Angeles music archivist and podcaster, Mark Guerrero, and Rick Rosas, bass player in Mark & the Escorts, who later recorded and toured with Neil Young, the reformed Buffalo Springfield, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

In the November 3, 2016 issue of The L.A. Weekly, writer Johnny Whiteside touted Thee Midniters. “A magnificent collection of mid-1960s teenage upstarts, Thee Midniters transformed themselves from a mere jam-happy rockin’ rabble to a musical ensemble of stunning ability. Driven by the two-headed songwriting monster of Little Willie G, a vocalist of gale-force lung power, and bassist-shouter Jimmy Espinoza, one of rock & roll’s all-time great wild men, Thee Midniters cranked out a flabbergasting stack of incomparable records. Whether smoldering balladry (“The Town I Live In”), classic instrumental jams (“Whittier Blvd.”), mad-dog garage ravers (“Jump Jive and Harmonize”) or flat-out, freaked-out psych-rock (“I Found a Peanut’), Thee Midniters excelled at every-damn-thing. While Willie G only occasionally rejoins today’s working Midniters unit, when he and Espinoza share a bandstand, it’s as fantastic a rock & soul summit as one could dream of.”

##

During 2012 I interviewed Thee Midniters’ singer Little Willie G.

Little Willie G: When I was ten years old, I went to the Strand Theater on Vernon and Main and watched the movie Blackboard Jungle. I heard Bill Haley & the Comets, and I was never the same.

I grew up in South Central. R & B is on the radio. Hunter Hancock is yelling about Gonzalez Park. He’s throwing these gigs in Watts at baseball diamonds like Wrigley Field.

I went to school on Thirty-Fourth and Central. St Patrick’s, a few steps from the Elks Ballroom on Jefferson and Central—this is where I first heard Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sarah Vaughan rehearsing for a show they were going to be doing at the Lincoln Theater. We made the trip every day to Flash Records and the Dolphin’s of Hollywood record shop.

I was sixteen or seventeen on my first trip to El Monte Legion Stadium. You needed a permit from the school district to go to the place. Don Julian and the Meadowlarks with the Penguins were on the show, along with Tony Allen, who had “Night Owl.” He was actually my neighbor. Richard Berry, Don Julian and the Meadowlarks, Jesse Belvin, and Tony Allen used to rehearse at Tony’s grandmother’s house. I would hear them and shine their shoes. When Jesse died in 1960, they had his funeral at the Angelus Funeral Home on Jefferson. My first singing quartet I was in, we went over there and paid our respects to Jesse, who is overlooked in history.

In 1960, when I started going to high school, I met Raul, Benny, and Richard Ceballos, and they had a band. The drummer was Jerry Ainsworth, who was an Orthodox Russian Jew who lived in Boyle Heights. As a dig to his dad, we called the band “the Gentiles,” ’cause every Wednesday, when we would pick up Jerry for rehearsal, we could hear his dad yelling, “Jerry! Jerry! What’s the matter with you, hanging around with those unclean Gentiles!” Every Wednesday, the same spiel. What a way to get back at his dad, by seeing our names on posters all over East L.A.

We were just a garage band. After a while, the name “the Gentiles” didn’t look as glamorous on posters as “the Romancers” and “Richard & the Emeralds.” So, we felt we had to change our name and image and we kicked it around, and Hank Ballard & the Midnighters were one of our favorite groups.

We all were throwing names into the hat that day. “Thee,” was Eddie Torres’s idea to set us apart, and thus started a wave of “Thee” bands all over the East Side. We talked a lot about who were our favorite bands, and Hank Ballard & the Midnighters was high on everyone’s list!

First, we changed the spelling of “Midnighters.” It could have been our manager, or someone in the band who suggested “Thee” at the front. Perhaps Bobby Cochran, Eddie Cochran’s nephew, was one of our guitar players in that early band. [We said,] “Let’s be ‘Thee Midniters!’ In 1961, it was Benny and Thee Midniters, and we did a battle of the bands at St Alphonso’s Hall [at East L.A. College]. We employed “Thee” in front of our band name because we wanted to emphasize who we were.

The group recorded in Hollywood on Melrose Avenue, at Studio Masters with Bruce Morgan, who was a godsend. He had worked with the Beach Boys there and was just an incredible guy. “What do you guys want to sound like?” We told him, “We want to sound the way we sound live, when we are playing on a stage or in a backyard.” There’s an energy, vibe, and cohesion with a unity that comes across.

We recorded over twenty-five singles. It was right across the street from Paramount Pictures in Hollywood. Studio Masters was right next door to Lucy’s El Adobe Café. It was not unusual to go into Lucy’s El Adobe and see Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner come in wearing full makeup during their lunch break from filming the Star Trek television series.

After “Land of a Thousand Dances,” the British Invasion happened in 1964 and 1965. At rehearsal, one of our warm-up songs was “2120 South Michigan Avenue” by the Rolling Stones, from their 12 X 5 LP. We needed a follow-up record for Chattahoochee Records. Samy Phillip [later known as Hirth Martinez] wrote a song, “Evil Love.” We went in and did it. Then Bruce Morgan said, “Okay, what’s the B-side?” And we looked at each other. We didn’t even think of that.

I suggested that we cut “2120” as a cover. Then Romeo Prado, the trombone player in the group, said we had to change it, you know. “Let’s put some horns on it.” Romeo is the architect of Thee Midniters’ sound. We also knew the value of instrumentals. Like, there were surf music instrumentals. The instrumental is not a novelty in East L.A. We were following James Brown. “Night Train,” those type of things. “Harlem Nocturne.”

The street Whittier Boulevard became a cruising mecca. They started coming from Orange County and the San Fernando Valley, and from the beach cities. Our audience was everybody. They’d come from San Pedro, Hermosa, Manhattan Beach, Van Nuys, Pacoima. They would come to Whittier Boulevard partly because of our song, but we also had three things in common: music, cars, and girls. You could find all that on Whittier Boulevard.

We weren’t throwing beer bottles at each other as the highway patrol and the sheriffs tried to make it out to be when they started to shut Whittier Boulevard down. There was actually an article in the Los Angeles Times where they blamed it on Thee Midniters’ “Whittier Blvd.” song. There was always white fear. Before Mayor Sam Yorty, it was Chief Parker. This goes back many years.

Thee Midniters had strong support from the local DJs. Art Laboe, Huggy Boy, [and] Godfrey, as well as Sam Riddle on KHJ and Casey Kasem and Dave Hull from KRLA, took us to the air force bases. We were Casey’s favorite band to book. He was an advocate of what we did, and then Dave Hull, and then Sam Riddle. They hired us for their private events and the dances they sponsored.

We were not stuck in a doo-wop bag, either. We were total entertainers. We played a lot of backyard, family-oriented parties. The older folks wanted to hear boleros; they wanted to hear corridos. Then you had the second generation that wanted to hear Duke Ellington and big band stuff—Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby stuff. We learned all that stuff. Because music really transcends borders and colors. I think our band was indicative of that. If you saw the band, you left as a fan.

We were a very versatile band. We added percussion and a horn section, before Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears. Johnny & the Crowns had a full horn section, but they never got recognized. If the audience was predominantly black, we could knock out some R&B like anybody else, like “Sad Girl” and “The Town I Live In.”

We played everywhere. We were able to go to Thousand Oaks and to Hawthorne for the Drop. We performed at the Rendezvous Ballroom on Balboa Island with Dick Dale. We toured a short season with Paul Revere & the Raiders in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

Thee Midniters played with the Turtles at the Rose Bowl. We used to hang out with the Lovin’ Spoonful whenever they came to town to play The Trip. Also, Them with Van Morrison. We actually took Them and Steppenwolf to East L.A. and the Big Union Hall in Vernon. Bought them a quart of vodka. We hung with the Young Rascals every time they were in town. Eddie Brigati of the group would come to East L.A.

We auditioned at most of the clubs on the Sunset Strip. But, at the time, they didn’t know what to do with an eight-piece band. That was not common. They were used to trios and four pieces, or four pieces with a singer. We were with the William Morris Agency for a little bit. RCA Records was checking us out when we opened up for Jose Feliciano. When we did our songs then, they were popular music and not oldies.

We did the Teenage Fair in Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard, and the audiences were all white kids. They were looking at us like we were aliens from outer space, some of them making really derogatory comments. “Where are your burritos?” We would hear stuff like that and ignore it, because we knew, as soon as we started playing, they [would] change their minds about us. That was our attitude. As soon as the music hit, they gravitated towards us. Sometimes they couldn’t get us off the stage. They kept calling us back.

Going to Hollywood was utopia for us. We grew up color-blind. Okay, even when the Chicano movement started, and the Brown Berets and those political factions would come and tell us that we were being exploited by the white man and whatnot, we never felt that. We were working. We were recording. We were sitting with record company executives. What they were saying to us didn’t register. We weren’t experiencing that, man—their whole concept and portrayal of what was going on in the world. We would hear them out and then have discussions about it. We didn’t get political with it. We took it someplace else after guitarist George Dominguez said, “I never knew we had it so bad.” George, drummer Danny LaMont, and I even wrote a tongue-in-cheek song, “I Never Knew I Had It So Bad,” for our third LP, Unlimited, on Whittier Records.”

##

East Los Angeles native Gene Aguilera’s history in the music and recording world has been featured in the Los Angeles Times, L.A. Weekly, and Goldmine Magazine. Lyricist, rhythm guitarist, and BMG writer Aguilera co-wrote “Poor Man’s Shangri-La,” the opening track on Ry Cooder’s Grammy-nominated album Chavez Ravine (with Cooder and Little Willie G), and “El Corazon Mexicano” with singer/songwriter Danny O’Keefe. Other Aguilera original songs have appeared on the FOX TV show “Space: Above and Beyond,” HBO’s movie “Cadillac Ranch,” and on albums by The Blazers, Little Willie G., and Thee East L.A. Philharmonic. Aguilera is listed as Associate Executive Producer on the The Paladins LP Slippin’ In and Creative Consultant on albums by East L.A.’s Thee Midniters: Thee Complete Midniters, Greatest, and In Thee Midnite Hour.

Aguilera has been acknowledged on recordings by Los Lobos, Cannibal & the Headhunters, the Premiers, El Chicano, and various East L.A. musical compilations. Gene is a USC graduate and hall of fame boxing book author Aguilera has written three books for Arcadia Publishing: Mexican American Boxing in Los Angeles, Latino Boxing in Southern California, and Lost Stories of West Coast Latino Boxing. His first title is currently listed by bookauthority.org as #56 on the “100 Best-Selling Boxing Books of All Time” as featured on CNN and Forbes.

Aguilera, known as “The Duke of Boyle Heights,” appears and is credited as Associate Producer in 18th & Grand: The Olympic Auditorium Story—the documentary by director Steve DeBro.

East Los Angeles Mexican Independence Day Parade, September, 1988. Left to right: Bill Garcia (Vice-President East Los Angeles Lions Club), Cesar Rosas (Los Lobos, guitarist, vocalist, songwriter), and Gene Aguilera (President of the East L.A. Lions Club, boxing book author/East L.A. music historian). Rudy Martinez (driver). (Photo courtesy Gene Aguilera)

Earlier this century I interviewed Gene Aguilera.

Do you have any theories why the musical heritage of East Los Angeles is constantly overlooked or neglected, as perhaps the least documented genre in the musical history of Los Angeles, West L.A. or Hollywood?

It’s been a nagging ache in my side, that the East Side Sound during its golden age of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s is almost never mentioned in the same breath as the Hollywood music scene. It’s like the suits never wanted to cross the bridge to East L.A. during those turbulent times. Thee Midniters, even with a hit single in tow, never got booked at The Whisky A Go Go probably due to cultural insecurities and insensitivities (combined with naïve management). The East L.A. sound (which combined doo-wop, soul, and The British Invasion) definitely shaped and influenced the musical landscape of the greater Los Angeles area.

The soulful, horn-drenched influence of Thee Midniters (who preceded brass bands as Chicago Transit Authority and Blood, Sweat & Tears) were one of the first groups to utilize horns as the driving force in a rock ‘n’ roll context. I call East L.A….the forgotten village. That is the perfect name for this colorful barrio that developed its own musical style, burst into the national scene in 1964 with several Billboard Top #100 charting hits, yet reviewers and documentaries of rock ‘n’ roll have traditionally turned a blind eye towards our musical contributions.

As you well know, as a journalist and author I have constantly paraded East L.A. for decades and cite the vision of Eddie Davis and Billy Cardenas and the influential Rampart/ Faro Records label. Why is the legacy of East L.A. and the surrounding area still perceived in some ways as a sleeping giant in terms of reporting and acknowledgment?

In the early days, maybe East L.A. was misunderstood. Maybe the exploding Chicano movement, made it difficult for Hollywood to cross racial lines in terms of sending a promo man to scour the barrio for new acts. The East L.A. music scene never seemed to grow past a certain point with the Hollywood shot-callers, maybe from mistrust on both sides. Talented groups and singers failed to receive a long-term recording contract with the major labels. The East L.A. golden age period has usually been stonewalled in the big picture of the pop-culture world, even though we’ve always been in the same city and across the bridge from downtown L.A.

In the 1990’s, I purchased two separate multi-volume documentaries titled The History of Rock ‘N’ Roll (Warner Bros.) and Rock & Roll (WGBN-PBS). After spending hours devouring these documentaries, I was dismayed to find out that not one word or photo was spent on the East L.A. sound. It is encouraging to note, though, producer/director Jon Wilkman released a fine documentary Chicano Rock!”– The Sounds of East Los Angeles–that appeared on PBS in 2008. It is worth checking out.

Some of these groups from the sixties and seventies still work and tour.

If record executives back in the day would have dared venture out of their leather seats and gone out to East L.A., they would have found and awoken a sleeping giant. They would have unearthed a buried treasure of music that was as different and creative as any music of the day coming out. “The Golden Age of East L.A. Music” was the ‘60s, and yes, they tossed a bone or two out to us (meaning the major labels released a one-time 45 single to a Chicano act; such as Warner Bros. distributing “Farmer John” by the Premiers, Reprise Records issuing “La, La, La, La, La” by the Blendells, or Atco Records putting out “I Who Have Nothing” by Little Ray). But as far as building a career or releasing an extensive backlog of music (i.e., a catalog of LP’s), it just didn’t happen for East L.A. artists. We had a unique style of music; which was a blend of R & B with the British Invasion sound. We had rock ‘n’ roll, garage, psychedelic, and soul; all blended into one pot . . . and it was delicious.

Today, you still can see Thee Midniters (with original lead singer Little Willie G) and Tierra in large venues, such as the Honda Center in Anaheim or Primm Valley Casino in Nevada. So don’t put us in a drawer yet, we’re not ready for the mothballs. There’s still lots of time to do some damage.

There’s an East L.A. underground indie trio going on right now called Thee Lakesiders. They sing cool, look cool, and dress cool. They are influenced by people like Ritchie Valens and Rosie & The Originals (“Angel Baby”). Anyway, if you get a chance, check them out.

Gene Aguilera, Cesar Rosas (Los Lobos) and Ruben Olivares (four-time boxing world champion and hall of famer) in Los Lobos trailer during the filming of the “La Bamba” video in 1987

Rock and roll music documentaries almost always leave out East L.A. Ritchie Valens is occasionally cited but he’s from Pacoima in the San Fernando Valley.

The East L.A. music scene is like a forgotten stepchild. We are around, but somehow left behind when the goodies are passed around. We seldom get mentioned in rock ‘n’ roll music docs or music history books, even though we had plenty of Billboard Top 100 charting hits.

Technically Ritchie Valens was from the Valley, but to East L.A, he was one of our own. A darn shame that we had to lose him at the ripe young age of 17 (even at that point, Valens already had three big hits to his credit: “La Bamba”, “Donna”, and “Come On Let’s Go”).

Thee Midniters had a horn section on disc and at shows.

East L.A.’s Thee Midniters, who released their first record in 1965, were possibly the first rock ‘n’ roll band with a full-time, working, and recording brass section. They were the forerunners to all the groups you mention above. It is a seldom mentioned fact in today’s rock literary world that Thee Midniters were probably the first rock ‘n’ roll band to incorporate horns into their live performances and recorded music canon. This must be corrected.

Case in point for rock’s first horn band: The Buckinghams came out in 1967. Blood, Sweat & Tears and The Electric Flag released their first records in 1968. Chicago Transit Authority (later Chicago) put out their first LP in 1969. Thee Midniters charted in 1965.

In the fifties, rock ‘n’ roll in Southern California was partially birthed and nurtured in venues like the El Monte Legion Stadium, Montebello Ballroom, and the Shrine Auditorium. Little Julian Herrera was a very big regional star.

Little Julian Herrera was an important early influence in the East Los Angeles musical canon. In 1956, Little Julian Herrera released his first single, “Lonely, Lonely Nights” on R&B bandleader Johnny Otis’ Dig label. To bluntly state where Herrera’s timeline is situated during rock’s early days—he arrived a mere two years after Elvis Presley first unleashed rock ‘n’ roll to the world in 1954, and two years before Ritchie Valens recording debut in 1958. Herrera, the first East Los Angeles rock ‘n’ roll star (even with assumed dual-identities), was raised by a Chicano family in Boyle Heights and frequently played the legendary El Monte Legion Stadium. His sudden drop-out from sight in 1960 qualifies him as a bona fide Los Angeles mystery that has never been solved.

Why did the audiences in East L.A. always have a very special and passionate link to Southland radio DJ’s like Art Laboe and Dick “Huggy Boy” Hugg? I know the same could be said about West L.A. and Hollywood and San Fernando Valley teenagers and fans relating to the DJ’s on AM radio stations KFWB and KRLA throughout the sixties.

Seminal East Side D.J.’s Art Laboe and Huggy Boy ruled AM radio and influenced barrio listeners with their dedications and community involvement; such as broadcasting live from Scrivners (a drive-in restaurant in Hollywood) and Dolphin’s of Hollywood (a record store on E. Vernon Ave). Ironically, the two greatest messengers of Chicano music, were not even of Mexican descent. Huggy Boy looked Latino and I think people related to that as he played all the popular East L.A. hits of the day.

Comedian Paul Rodriguez told The Los Angeles Times that ‘He (Laboe) is more Chicano than some Chicanos.’ Laboe started the popular Oldies But Goodies album series, which were categorized by a ‘Dreamy Side’ and a ‘Jump Side’, and invented the concept of “dedications” on the air. Consequently you were able to go on the radio and hear yourself, and if your boyfriend or girlfriend was listening on the other end, they also got to hear their name on the air. Before that, we never got on the radio at all, these guys were our voice. The Blendells (who hit with ‘La La La La La’) even cut a side called ‘Huggies Bunnies,’ named after Huggy Boy, so they could get airplay. Art Laboe and Huggy Boy were Chicano music ambassadors who owe their careers to the Latino community.

I talked to you and several East L.A. based musicians at length for my 2014 book, Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972. Can you discuss the still going musical legacy of Thee Midniters and other artists who still tour and make recordings? You have championed them and helped manage their work. The vision of Eddie Davis and or Billy Cardenas continue when we still hear on the radio Thee Midniters, the Blendells, the Premiers who first gave us “Farmer John,” Cannibal & the Headhunters, Tierra, and El Chicano.

Let’s explore the definite musical influence left by the East Side Sound that invaded the American pop-culture world. The 1950’s ended with Ritchie Valens tearing up the Billboard charts with his one-two, knockout punch of “Donna” (#3) and “La Bamba” (#22 ). The East L.A. music scene exploded in the 60’s with national charting hits: “Angel Baby” (#5) by Rosie and The Originals, “Farmer John” (#19) by The Premiers, “La La La La La” (#62) by The Blendells, and “Land of 1000 Dances” recorded both by Cannibal & The Headhunters (#30) and Thee Midniters (#67). This should have been enough to propel some of these artists into long-standing careers by major record labels, but it never happened. As it is, these songs are seldom played on the radio now days, let’s hope they will not be forgotten.

Thee Midniters were ‘The Godfathers of 60’s East L.A. rock ‘n’ roll’ and still occasionally perform with their original lead singer, Little Willie G. And when that event happens, it instills a pride in the audience, a kind of romantic and heartfelt notion that their hero is still there up on the stage and still vocally delivering with the same power as he did back in the day.

Art Laboe’s Latin Oldies Legend concerts today, with Thee Midniters as headliners, still pack them in today at Nevada’s Buffalo Bill’s Casino, Honda Center, and other top-line venues. In recent years, I have witnessed Thee Midniters at such venues as the Santa Monica Pier, House of Blues, Gibson Amphitheatre, Amoeba Records, etc. and their performance is as good as any band happening today. Even in this day and age, they don’t have to take a backseat to anyone.

Gene Aguilera, Ry Cooder), and Little Willie G. (Thee Midniters), during rehearsals for Cooder’s album Chavez Ravine in 2003 in Aguilera’s Montebello home.

Was there some sense of identity you felt by checking out and supporting the East L.A. recording world as you lived, and still live in the world of East L.A.? Or, was it just was available to you initially?

Born and raised in East Los Angeles, being attracted to the East L.A. sound was a natural progression. It was the soundtrack of my youth. I remember the first time I heard the single “Whittier Blvd.” by Thee Midniters on KRLA radio in 1965. It starts off, “Let’s take a trip down Whittier Blvd…..arriba, arriba,” it was rock ‘n’ roll with a soulful Latin flavor. It was wild, it was different than anything I heard on the radio. Then, the single began to creep up the local charts competing with artists such as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Four Tops, Sonny & Cher, James Brown, the Beach Boys, and the Byrds. When I found out that Thee Midniters were from East L.A., well, that just blew my mind. Here were these guys, from the same stomping grounds as me, competing with my favorite groups at the time. It made me proud that the local boys were becoming stars in the big picture. Thee Midniters had radio hits and appeared on television, ok….. Now we had hope.

I also think Frank Zappa was a bridge that tied in Doo-Wop and R&B and the music of East L.A. to the unique blend of rock ‘n’ roll he created from Echo Park and then Laurel Canyon. Zappa is one of your musical heroes. Why is he placed in your own pantheon of musical giants? Why did his first five albums have such an impact on you?

Growing up in East L.A., I was mesmerized by Frank Zappa’s first few albums. Beginning from Freak Out in 1966 (which even name checks Little Julian Herrera & The Tigers in the liners) to Just Another Band from L.A. in 1972, (which was credited to Las Mothers in resplendent cholo lettering by Limon), Zappa spoke Chicano directly to my heart. I don’t think I played another album more than We’re Only In It For the Money.

Zappa even had Chicano bass player Roy Estrada in the band during the early years. Zappa and Ray Collins (pre-Mothers of Invention) wrote the memorable East L.A. nugget ‘Memories of El Monte’ by the Penguins on Art Laboe’s Original Sound label. Zappa said in the liner notes of his doo-wop tribute album Cruising With Ruben & The Jets (1968), “The present-day Pachuco refuses to die!” Quoting “Dog Breath” from the Mothers of Invention Uncle Meat LP, “Primer mi carucha (Chevy ’39), Going to El Monte Legion Stadium, Pick up on my weesa (she is so divine).” As a kid, we used to crack up listening to the closing moments of “WPLJ,” from the LP Burnt Weeny Sandwich in 1969, as Mother Roy Estrada sings in secret Pachuco calo (street slang). It’s all in there, folks.

Have you been encouraged over the last few decades by the amount of CD reissues and boxed sets chronicling and re-positioning the initial sounds from East L.A. from the early sixties now reaching new ears? I know you’ve helped assemble many CD and vinyl re-releases or have been thanked in the credits for the distribution world.

I was proud to have worked on the 4-CD box set Thee Complete Midniters (Shout! Factory) that contains rare N-sides. Other releases I assisted in were In Thee Midnite Hour!!! (Norton), Greatest by Thee Midniters (Thump) and Little Willie G.’s solo CD Make Up For The Lost Time (Hightone). Some interesting East L.A. reissues are: Brown Eyed Soul (Rhino), The West Coast East Side Sound and East L.A. Rockin’ The Barrio (Varese Sarabande/Rampart Records), Latin Oldies (Thump Records), the 12-cd box set East Side Story (East Side Records), The East Side Sound (Dionysus Records), and Pachuco-Soul! (Vampisoul Records).

What the world needs now is the definitive DVD that digs deep into the archives of television programming to unearth original performances of classic East L.A. groups. Thee Midniters, Cannibal & The Headhunters, the Premiers, El Chicano, and Tierra all appeared on such television shows as Shebang, 9th Street West, Groovy, The Lloyd Thaxton Show, and Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. These performances need to see the light of day.”

##

Mark Guerrero is a musician, singer/songwriter, journalist, podcaster and East Los Angeles music scholar who has witnessed and involved in the world of East L.A. since the fifties. Visit Mark Guerrero’s Latin Legends website.

Mark & the Escorts.

Mark Guerrero: In 1964, my dad, who was a singer and songwriter [Lalo Guerrero, the father of Chicano music], received a phone call from producer Don Costa asking him to come to Western Recorders on Sunset, where he was working with Trini Lopez. They wanted him to write a Spanish lyric to a song Trini was recording, that my dad titled “Chamaka.”

Dad invited me to come with him to the session to help Trini with the lyric. I invited Richard Rosas from my band, Mark and the Escorts, to come along. We arrived at Western Recorders and were led into a big studio, where Trini was about to sing with a large orchestra. Strings and the whole deal. There might have been some Wrecking Crew guys in the band, but I didn’t notice them at that age. We met Trini and Don, which was pretty exciting for me and Richard. We were only fourteen years old and in some pretty impressive company.

We watched the session for a while, and then Richard and I went wandering through the hallways when I see these two blonde guys. “Are you Jan and Dean?” And they said, “No. We’re the Beach Boys.” It was Al Jardine and Mike Love. They said, “Come on in.” They didn’t know who the hell we were.

We walk in, and lo and behold, there was Brian Wilson at the board and all the other members. Nobody else. They were recording the song “All Summer Long,” and about to overdub some vocals. They were all around the mike, and we’re just sitting there in the control room, in front of the mixing board with Brian Wilson.

On a break, Dennis Wilson came over and handed us a couple of singles with picture sleeves of their soon-to-be-released “I Get Around.” I asked him to sign it, and Mike as well, on the back of the picture sleeves. We were thrilled to get the records signed. Then “I Get Around” went to number one on June 6, 1964.

Richard and I were sort of East L.A. music kids from the scene that had Cannibal & the Headhunters, the Premiers, [and] Thee Midniters, and here we are meeting the Beach Boys, purely by chance. And they couldn’t be nicer. We went back to the Trini Lopez session, which came out great. It was quite a night for a couple of teenage Chicanos from East L.A. Mark & the Escorts and the Beach Boys both played the Rainbow Gardens in Pomona.

Cannibal & the Headhunters, the Blendells, the Premiers, Thee Midniters. We loved the Blendells. We had the same manager, Billy Cardenas, so Mark & the Escorts were on the bill with them several times.

We did “Get Your Baby” for the Rampart label. We played with Cannibal & the Headhunters. I was proud of them, and they had a hit record, “Land of a Thousand Dances.” I saw them open for the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. And they were the only act that got any response at all. They were a dancing vocal group, like the Temptations.

Thee Midniters were probably the most popular group in East L.A. at that time, even with these other groups having hits. They got screams. They had the look; they were polished and smooth. Little Willie G, I always looked at like a Frank Sinatra—a skinny guy who sang ballads. That was his strong suit, and still is. The girls screaming. We liked them. “Whittier Boulevard” was a local and national hit.

Billy Cardenas describes himself as a vato from East L.A., this street kid. He just loved music. He took a lot of guys—for example, the Premiers, these lowrider kind of guys. Pachuco kind of guys. They were playing in the backyard, [and Billy] polished them up, got them in suits—sort of like what Brian Epstein did to the Beatles, but Chicano style. He managed so many bands. He was a record company owner and kind of a record producer sometimes, but more the manager. But Billy also was in the studio producing.

I’m just saying, if it weren’t for Eddie Davis, none of that would have happened. We needed his record labels, and getting the stuff out . . . his record savvy that created the Blendells and Cannibal & the Headhunters, it was essential. And we needed Billy because he was out there in the trenches, finding these groups and grooming them.

I was at all the classic recording studios: Gold Star, one time at Columbia with Little Ray [Jimenez]. He’s very important, and did “I Who Have Nothing” on Donna Records, [which was] distributed by ATCO. Arthur Lee, before Love, wrote the B-side “I’ve Been Trying.” Lee [and Johnny Echols] also wrote and worked with Ronnie & the Pomona Casuals on a recording.”

##

Many years before bass player Rick Rosas joined Neil Young, was in the reformed Buffalo Springfield, and a tour with CSN&Y, Rosas reflects on the vibrant music birthed in East Los Angeles.

Rick Rosas: Back then, people didn’t look at a racial or geographical divide between East L.A. and West L.A. See, people didn’t look at your color back in those days. I remember being in Garfield High School, and [there were] maybe three or four black guys in the school, and you treated them like brothers. They were all very good friends of mine.

Eddie Davis and Billy Cardenas were very important. They would release stuff on their little private labels, like Rampart, and it would get picked up by a major label because it was making noise in L.A., not just East L.A. Then it became national, like Cannibal & the Headhunters’ “Land of a Thousand Dances.” Cannibal & the Headhunters and the Blendells were very good. They were mentors, also. We opened up a lot of shows for them, and they showed us the ropes. We listened to all the same radio stations. Even KHJ played our first single on GNP Crescendo.

And there was always Thee Midniters. The records did them justice. Little Willie G, oh man, he was an entertainer. I looked up to him very much. And the bass player, Jimmy Espinosa, I took lessons from him. He taught me how to read. Thee Midniters were big mentors to Mark & the Escorts at the time. Cannibal & the Headhunters and the Blendells were very good. They were mentors, also. We opened up a lot of shows for them and they showed us the ropes.

AM radio initially connected everyone together and then FM radio changed the world a lot back then. The sound was so much better. And, DJ’s like B Mitchel Reed would play the extra-long version of Buffalo Springfield’s “Bluebird.” It was like 18 minutes. Nobody would do that on the radio. “Where did Mitch get that?” That could only happen in L.A. I loved the Beach Boys. Even before Mark and I were invited into their “All Summer Long” recording session.

And when I heard the first Mothers of Invention album Freak Out! I then freaked out. Great. “Help I’m a Rock.” I had no idea until later that Zappa loved doo wop and worshipped East L.A. It didn’t dawn on me his link to East L.A. He had a song “St. Alfonzo’s Pancake Breakfast” on his solo LP Apostrophe (‘) although the spelling of the church is St Alphonsus Catholic Church. I went to with my parents. That hall had teen dances. I saw Thee Midniters and the Mixtures, another great band. Black and white. That was the first time I saw an electric bass on stage. “I gotta get a Fender bass.” I got one at Phillips Music Store in Boyle Heights on Brooklyn Avenue. I still have the bass, a ’64 Jazz bass. My mom bought it for me. I still have the receipt.

Buffalo Springfield had a big impact on me. From their first record they just caught my ear. I just loved the guitar playing and the singing. It was like the California Beatles. They were just so good. I heard “For What It’s Worth” the first time driving around in East L.A. We’d end up in Hollywood every once in a while, cruising the Sunset Strip. Past Pandora’s Box, where Stephen wrote about it.

I think at the beginning of Buffalo Springfield, Stephen Stills stuck out the most. His voice was recognizable. And then as it went on, Neil’s voice slowly slipped in. He didn’t sing much on the first album. And when he did sing, he was so unique. It wasn’t perfect but it was great. And Buffalo Springfield had Richie Furay.

And when Mark (Guerrero) and I noticed that their first album was recorded at Gold Star studios in Hollywood, we needed to record there as well. We were kids. I could not believe we were at Gold Star. It made a big impact on us. Anything they did we had to go and try and find it. Then, Buffalo Springfield Again came out and I had my mind blown. To this day, that whole album is amazing.

We went to the Springfield goodbye concert in Long Beach. It was pretty heavy. I was so young. It was really good. Some of the guitars were out of tune. Then they came out with Last Time Around. Definitely blew my mind. That thing holds up to this day. I love that album. “Pretty Girl Why.” “Uno Mundo.”

Then I heard the first Neil Young solo album. My favorite of his. I have worn out two or three copies on vinyl. Neil with Jack Nitzsche.

Then six months later, Neil and Crazy Horse, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. A whole other direction. Mark Guerrero and I went to The Troubadour all the time. Saw the debut of Neil and Crazy Horse. Fantastic. He started out acoustic. I think he did “Sugar Mountain.” And then they rocked for an hour. They sounded great. Of course, we went to the Greek Theater to see the first Crosby, Stills & Nash show. Neil was now in the group. We paid, but may have snuck in one other night. That first album kicked me in the ass. And Déjà Vu which was another one that blew me away. I just fell in love with it immediately. Songs like Neil’s “Country Girl.” And I was always a big fan of the Byrds.

Many years go by and I end up playing with Neil in his Blue Notes group. “This Bud’s For You.” I did play with Neil at a little Mexican restaurant nightclub in Montebello on Garfield Avenue. We went down there one night because the sax player, Steve Lawrence, used to play there. “Let’s play a little club.” “Hey let’s do it!” We were at SIR. Next thing I know. We grabbed a few amps and went down there. Set up and played. It was hilarious. Neil later did a version of “Farmer John” on a Crazy Horse album.

I subsequently played with Neil on his solo albums and tours. And then Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

Neil’s tours had Buffalo Springfield tunes but this was Buffalo Springfield. And the front line of Neil, Stephen and Ritchie. All during my tours and recording with Neil, he and I would talk about Buffalo Springfield. I never hid my excitement about Buffalo Springfield and loved to talk to him about that band, sometimes over a couple of glasses of wine. He embraced the band. He loved it. Neil would talk about it as much as he could remember. He drove around in one of his first tour buses with the Buffalo Springfield logo on the back.

I was already a graduate of Neil Young University. That gave me a tremendous amount of confidence to take on this job. Dewey Martin and Bruce Palmer were definitely part of the original sound. I did my best to try and emulate Bruce to the best of my ability. I tried to play some of the parts because they worked so well. The shows were magic. And Neil used some vintage Buffalo Springfield gear. A couple of his guitars.

© Harvey Kubernik, 2023

A native of Los Angeles, Harvey “Roberto” Kubernik is a San Diego State University Aztec. The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican culture in central Mexico during the 1300 to 1521 period. Harvey’s devotion to the music birthed and produced in downtown Los Angeles and East Los Angeles during 1956-1972 were initially established from the records heard on his home and transistor radios at Coliseum Street Elementary School, El Marino, and Muirfield Elementary School in Crenshaw Village. Kubernik is a graduate of Fairfax High School, and briefly attended Los Angeles City College, before graduating West Los Angeles College and SDSU.

He is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2010, Kubernik served as Consulting Producer on director Morgan Neville’s Troubadours: The Rise of the Singer-Songwriter, Carole King/James Taylor.

In 2020, Harvey served as a consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood.

During 2006 Harvey spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 Harvey Kubernik appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, as part of their Distinguished Speakers Series.

Harvey was interviewed for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary on Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Bobby Womack, Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones, Regina Womack, Damon Albarn of Blur/the Gorillaz, and Antonio Vargas are spotlighted.

In 2019, Harvey was an on-screen interview subject for director Matt O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Christine’s family members, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, and Neil Finn

In 2023, Harvey, photographer Henry Diltz and authors Eddie Fiegel, Barney Hoskyns and Chris Campion were filmed by French director France Swimberge for her Mamas & Papas documentary. Broadcast scheduled on the European arts television channel, Arte. In addition, Kubernik is serving as a consultant for her film.

Harvey was lensed as an interview subject for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary on Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Bobby Womack, Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones, Regina Womack, Damon Albarn of Blur/the Gorillaz, and Antonio Vargas are spotlighted.

In 2019, Harvey was an interview subject for director Matt O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Christine’s family members, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, and Neil Finn.