-

Featured News

Shel Talmy: August 11, 1937 – November 14, 2024

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

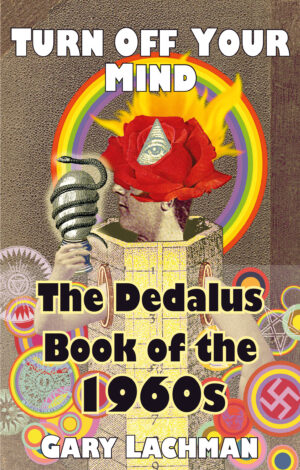

Turn Off Your Mind and float deep into the occult sixties: an interview with writer Gary Lachman

By David Holzer

LONG AVAILABLE ONLY in rare, overpriced second-hand copies, Gary Lachman’s essential Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius (2001) is in print again in the USA, with 100 extra pages of material, as Turn Off Your Mind: The Dedalus Book of the 1960s (2021), just in time for its twentieth anniversary.

From Jimmy Page and David Bowie to lesser-known figures like Graham Bond and American band Coven, to pick a couple at random, plenty of sixties and seventies rock &rollers were fascinated by the occult. But I can think of only one who has abandoned rock & roll for a career writing about the secret arts and major figures in its history.

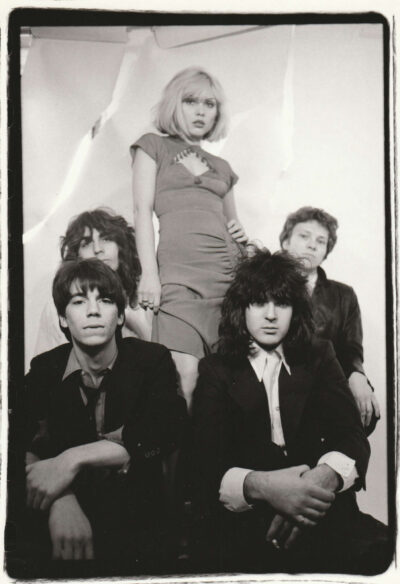

Formerly known as Gary Valentine, Lachman became famous as Blondie’s bass player. He also co-wrote their debut single “X Offender” with Debbie Harry and, by himself, UK top 10 hit “(I’m Always Touched by Your) Presence, Dear.” The latter was inspired by “paranormal experiences” Lachman was having with his girlfriend.

Lachman first acted on his curiosity about the occult when, as a 19-year-old, he borrowed Alistair Crowley’s Moonchild and Colin Wilson’s The Occult from band co-founder Chris Stein.

By the time Blondie set off on a major tour in 1977, Lachman’s fascination had blossomed. In New York Rocker, his 2006 account of his rock and roll years, Lachman tells the story of a porter at JFK asking him if he’s got bricks in his tour bag. By then, Lachman writes, “My magic studies had become quite serious and my bag was filled with books on tarot, kabbalah, astral projecting and the Golden Dawn.”

After Lachman left Blondie in 1978 and moved to LA, he formed The Know. The name comes from Gnosticism, “a mystical teaching that had grown up in the first centuries following Christ and which later influenced people like the psychologist Jung.”

Gary Lachman (left) onstage with Blondie, ca. 1977. (Photo: Lisa Jane Persky)

In LA, Lachman joined a magic group that followed Aleister Crowley. He went deep into “Crowley’s magick, performing rituals, wearing robes, developing my astral vision, practicing tarot and engaging in various other occult activities. I was initiated into two of Crowley’s magical societies, the A.A. and the O.T.O dedicated to his religion of Thelema, which was centered around discovering your ‘true will’. The ceremony took place in a tent in a room in some LA suburb.”

Strangely enough, another band lumped in with punk and power pop, the UK’s Eddie & the Hot Rods, had a hit in 1977 with a Crowley-inspired hymn to the will called “Do Anything You Wanna Do.” The original cover of the single showed Aleister Crowley sporting Mickey Mouse ears. This, according to rock & roll writer Peter Watts, offended Jimmy Page, a well-known Crowley admirer.

Page apparently placed a curse on the Hot Rods for “their disrespectful treatment of the Great Beast. From that moment, the band were plagued with problems.”

After The Know failed to enlighten the world of pop, Lachman did two tours with Iggy Pop, “riding shotgun on the Wild Bunch tour” as he described it to me, in a band that included Clem Burke, Blondie drummer, and Lachman’s friend Rob Duprey from The Mumps. They backed Iggy at the notorious 1981 Pontiac Silverdome shows near Detroit when he supported the Stones. During the second night’s show, Lachman writes in New York Rocker, Iggy wore “a white blouse, a brown leather miniskirt and a pair of coffee-colored stockings. He neglected to put on any underwear.” The band was pelted with an astonishing array of missiles, even more than were thrown at Iggy & the Stooges by audiences at the 1974 shows immortalized on the Metallic KO album. Maybe some of them were the same people.

After this, and as a result of his extensive reading, it’s not surprising that Lachman felt he’d gotten “too smart for rock & roll” and walked away.

He used his royalties from “Presence, Dear” to take time out and read everything he wanted then travel. In 1983, he made a pilgrimage to the end of Cornwall in the far west of the UK to meet Colin Wilson. After this, he began the career as a writer that, apart from playing with Blondie in 1996/97, he’s pursued ever since. Turn Off Your Mind was the first of Lachman’s 24 books to date.

Inside Turn Off Your Mind – this way for the darkness

Lachman was inspired to write Turn Off Your Mind because “it struck me that there was a gap in ‘sixties-ology’.”

What was missing was a book that focused on the occult and mystical revival brought above ground by the Beatles and Stones which became a magical way of thinking and living. This – manifested in anything from QAnon to The Secret-still resonates today.

For Lachman, the occult revival liberated the attitude articulated in aphorisms like Crowley’s “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law,” the dark mantra “Nothing is true, everything is permitted” popularized by William S Burroughs or, indeed Lennon’s “Turn off your mind”. This permission let in the darkness supposedly beyond good and evil that’s most graphically illustrated by the activities of Charles Manson and his Family.

Turn Off Your Mind is mostly concerned with this darkness. This is fair enough. As well as meaning a branch of the magical arts, the word “occult” is defined as hidden from view and not easily apprehended or understood. Also, we can’t help but be fascinated by darkness, chaos and disorder. It’s why the Velvet Underground, The Doors and The Stooges are more intriguing than Quicksilver Messenger Service, say. It’s why the story of Altamont is more gripping than that of Woodstock. It’s definitely why I’m endlessly curious about figures like Syd Barrett, Roky Erickson, Skip Spence and Craig Smith AKA Maitreya Kali.

The dark side of the summer of love makes for a better story, as Lachman’s literary mentor Colin Wilson, who also wrote about sensational crimes, knew. It was Wilson who suggested that Lachman start Turn Off Your Mind with the Tate-LaBianca killings in August 1969 committed by members of the Manson Family that, he writes, “ended the naïve optimism of the flower generation.”

As Lachman told me when we spoke, “When I first started, I was writing in this kind of philosophical way, trying to make some sociological point. I sent the manuscript to Colin and he said ‘What are you trying to do? You sound as if you think you have something to say or there’s some point you’re trying to make. Just tell the story!’ First I was angry then I thought I’ll do what he says. And it was bang, there’s Manson. The cleaning woman opens the door and there’s blood on the doorstep. And Colin said, ‘You’ve got it, that’s the ticket.’ And then I just went for it.”

Rereading Turn Off Your Mind after I’ve spent the last 15 or so years practicing yoga and meditation, visiting psychic surgeons and generally indulging in touchy-feely spiritual tourism, Lachman emphasizes the dark side a bit too much for me. I have some sympathy with Paul Krassner who, writing in the LA Times in 2002, criticized the book for ignoring the positive aspects of “a mass awakening that provided hope, inspiration, joyfulness and a sense of community to countless young people.” Although today, the issue of psychedelic legality is still a largely debated topic, there’s definitely plenty evidence to show its usefulness-the positive effects of the mass awakening (that is still propagating itself) being one of them. But Lachman is very clear that he isn’t writing a book about peace and love.

In any case, the real value of Turn Off Your Mind for me, and for you if you haven’t read it, is as a quite breathtaking introduction to an enormous number of books, characters and movements within the sixties that act as gateway drugs into any aspect of occult, magical and sacred thinking and practice you care to explore.

Just to give one example, Turn Off Your Mind led me to The Morning of the Magicians by French authors Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier. This, translated and published in English in 1963, became a bestseller in the US and shone some light on the occult revival. It also introduced the idea that the Hitler and the Nazis were fascinated by the occult. I find it unreadable, but I’m glad to own a copy.

From there, Lachman covers the occult side of the sixties and early seventies at a ferocious gallop, making satisfying connections along the way. The best way to illustrate this is to quote three chapter descriptions:

Introduction: Shadows of the Golden Dawn

Introducing Mr Manson. From Woodstock to Altamont. The Age of Aquarius. The occult revival of the 1960s. Eliphas Levi, Madame Blavatsky and the roots of the occult revival.

Chapter Seven: Food of the Gods

Leary, Harvard and a modern “mystery school.” Allen Ginsberg wants to call God. Michael Hollingsworth’s mayonnaise jar. Dr Leary takes a trip. The World Psychedelic Center. The IFIF. Castalia. Leary and Gurdjieff. Guru Tim heads East. Leary, Crowley and Dr Dee in Bou Saada.

Chapter Thirteen: The Occult Explosion

A crucifixion on Hampstead Heath. Kohoutek fizzles. Man, Myth and Magic. Occult consumerism. The occult publishing boom of the 1970s. Earth mysteries. The New Age. “Roccult” and roll, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and “back-masking.” David Bowie and those occult Nazis again. Satan, Manson and “Reich and roll.” The 8/8/8 satanic rally. Charlie and the “ecofascists.”

There’s nothing like Turn off Your Mind. It’s the one reference book for the sixties you really need.

Gary Lachman.

(Photo: Max Jones-Lachman)

An interview with Gary Lachman

SINCE READING Turn Off Your Mind, and rereading it a few times, I’ve read a number of Lachman’s books and would especially recommend A Dark Muse: A History of the Occult (2005), The Caretakers of the Cosmos: Living Responsibly in an Unfinished World (2013) and the excellent Dark Star Rising: Magick and Power in the Age of Trump (2018). So I was delighted that, through a suitably strange connection, I was able to interview Lachman about Turn Off Your Mind and, as it’s republished for in the US for the first time in 20 years, its significance. We met online. Lachman was in London and I was in Hungary.

Gary, it’s unusual to speak to an academic who’s an observer of occult and magical practices but has also taken part in the rituals.

I wouldn’t call myself an academic. I’m also not particularly spiritual. I don’t think you have to be spiritual in the clichéd way to pursue ideas about expanded consciousness or more intensified consciousness or just strangeness.

A scholar then.

I started out an enthusiast reading paperbacks and got more and more interested the more I read. It was a while before I began to take it more seriously in terms of the scholarship. But the idea that this stuff is “cool” – that is, exciting – is at the heart of it. I’m glad that esoterica and Hermetica [mystical philosophical texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus written in late antiquity] and all of that has made it into the academic world but then it takes on a certain sheen. In a way, it’s like CBGBs was before everyone got signed. It was more exciting when it was obscure.

My friend and colleague in California, author and journalist Erik Davis, is always saying “Keep it weird” because, today, in the psychedelic and spiritual worlds, taking substances and exploring inner realms are encouraged but only within safe conditions. Erik’s saying “No, just take the stuff and see what happens” (laughs) which is what people like William James [philosopher, who found “intense metaphysical illumination” using laughing gas] did in the first place. I still have that kind of excitement.

The stuff you’re writing about has to have some sense of adventure because it’s precisely about unexplored regions of your being and all that.

Your interest in these regions was originally triggered by a love of comic books, right?

Absolutely. As a kid I was completely absorbed in comic books. I had a huge collection. There was one comic, DC’s Legion of Super-Heroes, teenage superheroes from different galaxies, that had a character called Cosmic Boy. He had magnetic powers and I didn’t understand why he wasn’t called Magnetic Boy. I asked my sister what “cosmic” meant and she didn’t know. I asked my mother and she didn’t know either. I guess I’ve been trying to find out ever since.

Jeffrey Kripal has written a lot about comic book heroes being the carriers of this magical, mystic, hermetic knowledge. Check out his book Mutants and Mystics. You also have the 1960 movie Village of the Damned about these blonde, shining eyed children who all look the same and have scary powers. In Turn Off Your Mind I mention this film along with the X-Men comic, which started in 1963, and the hippies that started calling themselves “mutants” a year or two later.

It feels a bit dismissive to call Turn off Your Mind a primer, but it was the first book I read on the subject. It seems to me that it paves the way for books that take a deeper dive. To name just a couple on my bookshelves, I’m thinking of Love, Sex, Fear, Death: The Untold Story of The Process Church of the Final Judgement by Wylie and Parfrey or Season Of The Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll by Peter Bebergal. Would you say that’s accurate?

I would say yes. For instance, Jeffrey mentions me in Mutants and Mystics. I’m trying to be a popular writer of ideas. I want to write in a way that engages people and not just talk to colleagues who are already studying the subject. I joke that in an age of specialization, my specialty is being a generalist. I just read and then try to put it all together, tell a story in some way, push a narrative toward some synthesis.

I imagined you in the British library hauling down dusty volumes that hadn’t been opened in years. Does any of that happen?

I used to haunt it but, because of COVID-19, I haven’t been there in a long time.

Rereading Turn Off Your Mind for, I would think, the fourth or fifth time, I was struck all over again by how well it flows, the elegance of the narrative but also by the emphasis on the dark side of the sixties. You mention the Paul Krassner LA Times review in your afterword, where he talks about your focus on the darkness. You still seem peeved.

There are dozens of books about how groovy the sixties were. You don’t really need to add another one. And I didn’t set out to do that.

I tell the story of how the book came about in the first edition. I went to a celebration at the ICA of the 30th anniversary of the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream held at Alexandra Palace in 1967 where Pink Floyd headlined over bands that included Soft Machine, the Pretty Things and Tomorrow. This was in my first few months of living in London. I said something and, off the back of that, I was invited to give a talk at Wolverhampton University.

Realizing that Crowley was everywhere in the sixties – including on the cover of Sgt Pepper’s – I thought I’d give a talk about that. Someone at the talk said that it sounded like it would make a good book, he said to put a proposal together and he’d give it to his editor. I started writing. As I did, I noticed that there was a lot of stuff going on in the sixties that was similar to what happened in pre-Nazi Germany in the twenties – back to nature, free love communes, an interest in the occult, and the like. This history was new and exciting to me.

Now, I grew up in the sixties so, say, people like Alan Watts [a British writer and philosopher who popularized Buddhism, Taoism and Hinduism in the US from the forties onwards and was an influence on the counterculture] were the good guys. But I started to look at them in a different way. For instance, is Alan Watts leaving his wife and six children to go and live in Sausalito or wherever it was actually a good thing? When I was younger, things like this seemed to be acts of liberation and set the norms. But were they really? I came up with a different way of looking at the sixties rather than just writing another book about how great they were.

You start the book with Manson and the Family. When I saw Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood movie, I didn’t realize at first that it was a fairy story, about rewriting history. In the movie (spoiler alert) Sharon Tate doesn’t die. To me, this was incredibly moving. It also showed how much the figure of Manson is still embedded in pop culture as a signifier of something that went terribly wrong. How do you feel about Manson now?

I don’t think about him much. In a way it’s as you said earlier about how Turn Off Your Mind set the hares running then other people followed. I think it’s like that with Manson. His story has grown into something that multiplies itself. I still have people getting in touch with me saying “He wasn’t like that.”

To go back to your rock and roll years, you tell a great story about a difference of opinion with you had with David Bowie, who was notoriously interested in the occult in the sixties and seventies, in New York Rocker.

I was an enormous Bowie fan in my late teens in New Jersey. My friends and I were the ones putting makeup on and risking getting beaten up by greasers or bikers on our way over to New York. I lost interest when he got into Young Americans. The first tour Blondie did with Iggy in 1977 Bowie was playing incognito, but he was there all the time. Bowie’s interest in the occult comes up a lot but, to my mind, he was more of an artist who used it for inspiration than what we might call a serious student. A lot of artists do this kind of thing. No too many get into it in any kind of serious way, but it gives them something to work with. The story with Bowie was that I was at a gathering at his loft if NYC, it must have been 1981, and he was saying things about Colin Wilson, that he was a witch and practiced black magic, and got in touch with the spirits of Nazis. I said “David, that’s not true.” He insisted it was and I had the temerity to disagree.

In the book, you describe yourself being firmly ejected by David’s female bodyguards, “large girls like…centerfold assassins” because David “doesn’t care to be contradicted.” Bowie somehow embodies the whole progression you write about in Turn off Your Mind, from comics to Nietzche’s übermensch – for example, the track “Quicksand” on Hunky Dory which, to me, suggests he’d devoured The Morning of the Magicians – to the supposed flirtation with Nazi occult and the mysticism on the title track of the album Station to Station. How do you feel about the fact that he’s a national treasure in the UK?

This is what a friend told me the English do with their rebels, someone like Bowie. They make them a national treasure. There’s a portrait of Aleister Crowley in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Back in the 1920s Crowley was “the man we want to hang,” but not that way. He was neutralized by becoming a typical English eccentric. I mean, Mick Jagger got a knighthood.

Blondie. (Photo: Lisa Jane Persky)

###

JEFFREY KRIPAL AND ERIK DAVIS ON TURN OFF YOUR MIND

“What Gary was tapping into with Turn Off Your Mind was this churning countercultural cauldron of ideas and experiences that have been so culturally productive but sometimes also destructive. I read Gary’s book to write Mutants and Mystics, about the real paranormal experiences behind sci-fi and comic books. I’ve probably read seven or eight of his books since then, all of which I find remarkable for their scope and grasp of the topics-he’s encyclopedic, but he also knows. What I so appreciate about Turn Off Your Mind is that he doesn’t hesitate to look at the dark side of the counterculture as well as the light side. As someone who studies religion professionally and who understands “the sacred” as morally ambiguous, I always look for that same complexity as a sign of historical accuracy, philosophical nuance, and intellectual depth. Gary’s writing displays all of that in abundance.”

Jeffrey J Kripal is the Associate Dean of the School of Humanities and holds the J. Newton Rayzor Chair in Philosophy and Religious Thought at Rice University. I thoroughly recommend his Mutants & Mystics.

“Gary’s book was a game changer. At a time when the sixties counterculture had congealed into an easy myth, he excavated the contradictions, errors, and dark veins of psycho-pathology, delusion, and hedonic indulgence that ran through the scene. In addition to that excavation, he embedded the sixties experience in a longer history of the esoteric imagination, showing the hippie experience against the backdrop of the Theosophical New Age, California Vedanta, and the weird fiction of the early pulp magazines like Weird Tales. By combining his historical knowledge of these esoteric roots with a critical but not entirely jaundiced eye towards the contradictions of the scene, Gary offered a critique that opened up further questions rather than simply mocking or rejecting. Finally it was the opening salvo of what has been an extraordinary career as a popular historian of Western esotericism who balances skepticism, historical rigor, and sensitivity to the mystery that courses through things.”

Erik Davis, author of High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies