-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

The Phantom Brothers – Germany’s Wildest Beat Group

An Interview with Olgerd Wokock by Mike Stax, with Anja Dixson

(This article was originally published in UGLY THINGS #24)

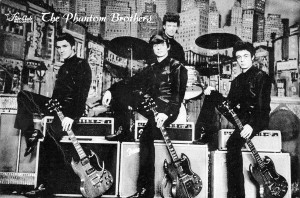

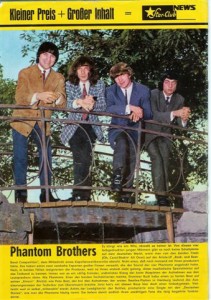

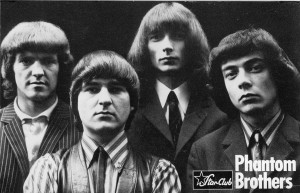

The Phantom Brothers, 1965. L to R: Rudi Kruger, Horst Kruger, Olgerd Wokock, Wolfgang Wokock (Photo by Astrid Kirchherr)

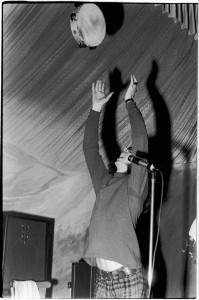

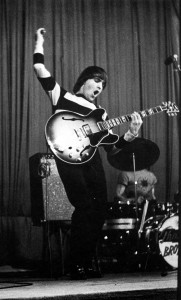

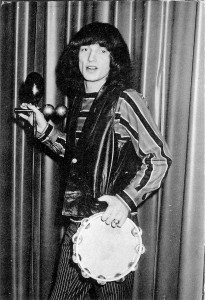

In my personal Sixties rock’n’roll pantheon Germany’s Phantom Brothers occupy a special place near the very top of the heap. I actually became a fan of the group before I’d even heard a note of their music, my enthusiasm based entirely on a set of photos in the German pictorial book, The Beat Age. Surly and stone-faced, decked out in leather and stripes, and with a lead singer with hair down past his shoulders—in early 1965!—they exuded style and attitude. And the live shots, with that singer shaking maracas and tambourine together, and a guitar player windmilling his arm Townshend-style, suggested a sound that couldn’t be anything less than flat-out WILD, man.

And wild, wild R&Beat music was what I was craving most of all back then, in 1980-83. Still is, actually. I was playing bass guitar with the Crawdaddys at the time, and bandleader Ron Silva and I obsessed constantly over these mysterious Germans, especially that longhaired singer, whose name, we learned, was Olgerd, a word we began to utter daily with awed reverence, like some mystical password to the Kingdom of Cool. An article on the Brothers in the late, great Gorilla Beat fanzine fueled the obsession further. We still hadn’t heard their music, but judging from their Chuck Berry-heavy discography, the Phantom Brothers were kindred spirits. Noting that they’d recorded Chuck’s “Run Rudolph Run,” we added it to our live set without delay, playing it year-round, despite its Christmas theme.

When Gorilla Beat editors Hans-Jurgen Klitsch and Alfred Hebing sent me a couple of German beat mix tapes we finally got to hear the band’s music. Amazingly, there was no sense of letdown—in fact the song “Chicago” exceeded all of our overblown expectations. That, too, was added to our set, and eventually recorded. (It later appeared on an obscure Spanish EP.)

More than 20 years later the Crawaddys were long gone, but my love of the Phantom Brothers was undiminished, so I was blown away when I received an email last year from Olgerd himself, closely followed by a CD of the recently reunited band, sounding, to my astonishment, virtually the same as they had in 1964-66. An interview was immediately arranged, and was conducted by email, with Anja translating our dialogue to and from German, allowing Olgerd to answer more comprehensively in his own language. Olgerd also dug through his scrapbooks and pulled out some remarkable previously unpublished photos to illustrate the story. So without any further adieu, we present Germany’s Wildest Beat Group: The Phantom Brothers!

Olgerd Woköck was born in 1943 in the port city of Memel, where the River Niemen meets the Baltic Sea. His brother Wolfgang followed a year later. Memel had a long history as disputed territory. The city’s population was mostly German, while the surrounding countryside was inhabited predominantly by Lithuanians. After World War One, the Treaty of Versailles separated Memel from Germany and it was governed by a French administration until 1924 when, after an uprising, Lithuania took control. A decade and a half of Lithuanian rule ended in March 1939, when the city was turned over to Hitler’s Germany.

“My father was in the German Navy and my mum was from Lithuania,” says Olgerd, “but she was made German when Memel was occupied. There she met my father. This is why my first name is Lithuanian.”

Strategically vital as a German port, the city was fiercely defended during the war, but by late 1944 Russian forces were advancing, and in October the German civilian population was evacuated. However, the Woköck boys and their mother remained where they were. The Red Army entered Memel on January 28, 1945, and the Soviet occupation began. (In 1947 Memel was renamed Klaipeda and became a part of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic.) After waiting out the cold winter, Olgerd’s mother and her sister fled the city on foot in the spring of 1945, carrying young Olgerd and baby Wolfgang with them. They headed for the Bavarian Forest region, eventually settling in Bamburg.

Meanwhile, the boys’ father finished his time in the Navy and settled in Rendsburg in northern Germany, where he worked as a machinist. The couple decided to divorce, and this literally split the family in two. “After the divorce my dad took me from Bavaria,” says Olgerd. “Wolfgang stayed with mum. I had very loving foster parents with whom I lived until I was five years old, at which time I had to go to school and moved in with my father and his girlfriend, who had two daughters.”

It was a difficult upbringing, but the young boy found refuge in music. “As my family life was not very happy, I looked for my luck in rock;n’roll music,” he remembers. “First, I was listening music through jukeboxes. It was hard to get records. Whoever had records played them to the others on portable record players, also [on the radio] in the car. When you heard the music you were very happy, it was a kind of freedom—a liberation, the teenagers dancing to jukeboxes.”

Olgerd soon had the itch to start playing this music himself, and in his late teens bought an electric guitar after saving up his earnings from working on a farm. Soon afterwards, around 1959 he met two brothers with a similar taste for rock’n’roll, Horst and Rudi Krüger. “The brothers Krüger were also refugee children, from Pommern, Neu Stettin,” says Olgerd. “They fled from there to Rendsburg.”

“The Krüger brothers were real rocker types and I was more a James Dean type,” he continues. “I met Horst first and we started to practice. Soon afterwards, Rudi bought a Senor drum kit and we were three without a bass guitar. We even played a few shows like this.”

Meanwhile, back in Bavaria, Olgerd’s brother Wolfgang had also caught the rock’n’roll bug, and was playing guitar with a band called the Tornados. After a little persuasion, Olgerd convinced him to move to Rendsburg and join their band instead. “He actually was the lead guitar player in the Tornados, but with us he played the bass. Later on he traded with Horst and played lead guitar and Horst played bass. There were also songs when I played the bass.”

After growing up separately for so many years and only seeing each other during school vacations, the two Woköck brothers were finally reunited. “We first came together through the music,” says Olgerd. “That was a beautiful feeling that we were reunited through rock’n’roll.”

The three-piece group had named themselves the Phantoms, after hearing a record on the radio by a French group called Les Fentomes, a guitar instrumental version of “The Breeze and I.” With the addition of Wolfgang, the group was now two sets of brothers, so they renamed themselves the Phantom Brothers.

“We were professionals from the start, never amateurs,” asserts Olgerd, “and decided always and ever to play professionally. I finished my apprenticeship and Horst and Rudi Krüger were unemployed, so our decision was to be professional, immediately. We, the 2 x 2 brothers, played almost 10 years in the original line-up. In such a length of time, other bands were changing members like shirts!”

At first the group’s repertoire was mostly instrumental. “For about a year we were playing in small clubs in the north of Germany,” remembers Olgerd. “We played mainly instrumentals by the Shadows and the Ventures, but also some vocal pieces, for example ‘Sweet Little Sixteen,’ ‘Peggy Sue,’ ‘Baby I Don’t Care’ and ‘Rave On.’ At the beginning it was only me singing. The audience was very into it and was dancing to every song we played, including the instrumental pieces.”

As the vocal numbers started to get more reaction from the audience they added more of them to their set, favoring revved-up versions of ’50s rockers like “C’mon Everybody,” “Jenny, Jenny,” “Be Bop A Lula,” “Say Mama,” “Mean Woman Blues,” “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” “It’ll Be Me” and “What’d I Say,” a repertoire not dissimilar to hundreds of other groups at the time, including a certain four-piece from Liverpool whose act the brothers had caught in Hamburg.

“We saw the Beatles live at the Top Ten before they had their big break,” remembers Olgerd. “Then we saw them at the Star Club after the release of their first LP. They were really active on stage and were already very popular.”

Hamburg was the epicenter for the beat music explosion in Germany, and by the end of 1963 the Phantom Brothers had relocated there to be a part of the big city action.

“We began playing clubs in Hamburg very early on,” explains Olgerd, “places like the Hit Club (now called Grün Span), the Thäder, the Honululu, the Aussenmühle, but afterwards always drove home to Rendsburg. After three-quarters of a year we were hired to play the Star Club in Hamburg and after that time we lived there. In other towns we were the only band on the bill, but at the Star Club in Hamburg we only played for an hour at a time, and then it was the next band’s turn. That meant that we were waiting about three or four hours until we played. The Star Club had a stage with a motorized curtain. You were tuning your instruments, and then you were announced by the stage manager: ‘And now, The Phantom Brothers!’ The curtain would open and then we played.”

The Phantom Brothers’ first recordings were recorded live on stage at the Star Club. “Oh Carol” and “Shakin’ All Over” appeared on an Ariola beat sampler Rock and Beat Band Competition in early 1964. According to Olgerd, their frenetic cover of the Chuck Berry nugget pre-dated the Rolling Stones’ similarly fast-paced version, which first appeared that April on their debut album. The Stones, though, soon became a major influence on the Brothers.

“At the time we played about 30 Beatles songs, but dropped them pretty quickly when the Rolling Stones came along,” says Olgerd. “Then we played Stones songs, Chuck Berry songs, Kinks and also blues stuff. This went so far that people started calling us ‘The German Rolling Stones’ or later [comparing us to] the Pretty Things. We never saw the Stones live, and maybe that was a good thing, because that way we had our own show and not a copy.”

Around March of 1964, the band flew over to England, along with Tony Sheridan and the Four Renders, and played a show in Liverpool. “The boss of the Star Club, Manfred Weissleder, organized a Battle of the Bands in Liverpool at the Iron Door Club, similar to the Cavern Club,” remembers Olgerd. “We flew in three little charter planes, without work permits. We played rock’n’roll and Beatles songs, which went down really well with the kids.”

While there half the band underwent an image transformation. “We all still had rocker haircuts,” says Olgerd, “so the girls in Liverpool combed Horst’s and my hair to the front to make them into Beatles hairdos. Wolfgang and Rudi did not go along with that and still had the rocker hair for months after.”

On April 4, 1964, the newly made-over Brothers played a huge show at the Deutschlandhalle in Berlin, opening for Jerry Lee Lewis. “There were about 12,000 people in the audience,” recalls Olgerd. “Jerry Lee Lewis and the Nashville Teens were the top acts, then Johnny & the Hurricanes, Tony Sheridan and the Bobby Patrick Big Six. We were the first band on the list, and the only German band. We played dressed in black, with black leather waistcoats. We were only just back from Liverpool, and Horst and I had Beatles haircuts. The people had not seen that before, and were crazy about it. We played a mix of rock’n’roll and Beatles songs. The people went crazy as we finished, and carried me on their shoulders off the stage during the start of Tony Sheridan’s set. It was a great feeling!”

Lewis, with the Nashville Teens backing him, was in formidable form at the time, as evidenced by the live album he recorded the next night in Hamburg, widely considered the greatest live rock’n’roll record of all time.

A few months later, the Brothers’ biggest idol, Chuck Berry, was in town for a show at the Star Club on June 5, 1964. “The day before the show he was sitting with Star Club manager Horst Fascher and a nice girl named Peggy at a table, and he listened to an hour of a Phantom Brothers gig,” says Olgerd. “In his honor we played mainly Chuck Berry songs. Horst Fascher came later and told us, ‘Tomorrow, when Chuck Berry is playing, you have the day off. You don’t have to play.'”

“Too many Chuck Berry songs in one evening?” he speculates.

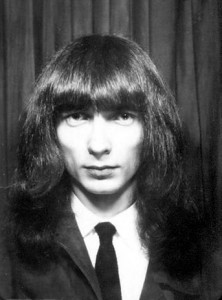

By the beginning of 1965, the Phantom Brothers had gathered a reputation for being the wildest band on the scene. Their show had always been hard-hitting and more energetic than most, but it began to get even crazier as the band’s appearance changed from leather-clad rockers to longhaired savages. “I said to myself, if you’re gonna wear a Beatles haircut, you will do it thoroughly,” explained Olgerd in a 1980 interview with Gorilla Beat. “So I decided to never cut my hair again—which I didn’t, until the band broke off.”

“The Phantom Brothers were the hardest and most punk-like band that performed at that time,” states Dieter Horns of the German Bonds (quoted in Bear Family’s spectacular 4CD box set, Die Ariola Star Club Aufnahmen). “Later on, maybe the Pretty Things were similar to that. The Phantom Brothers came from the country, but they were so uncompromising in their act that we all could do nothing but pay our respects.”

Before long Olgerd had the longest hair on the scene, and by late 1965 it was past his shoulders, longer even than Phil May’s famously outrageous tresses at the time. “In those days in Germany my hair was uniquely long,” says Olgerd. “It was not that common yet, and you only knew it really from the Pretty Things.” (The two bands crossed paths in June 1965, when they played together at the Star Club.)

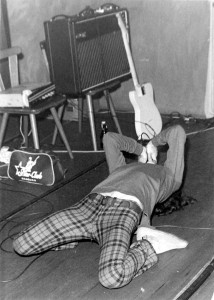

“As my hair got longer we had a show where we played a medley of ‘Pretty Thing’ and ‘Mona,'” Olgerd continues. “For that part of the act I did not play the guitar, just harp and maracas. I managed to get into a state of ecstasy, without drugs, and whirled wildly around with my hair and let myself fall backwards from the stage into the audience. They used some of the first strobe lights and the show was very wild. We also had an act with ‘Satisfaction,’ ‘Wild Thing’ and ‘You Really Got Me.’ When we played in little towns the girls were often shocked, as they had never seen anything like it.”

In July 1965, the band hit the road as part of a package tour with the Rattles and the Liverbirds, entitled “Star Club Beat Jamboree ’65.” “This was a tour of 22 German towns,” says Olgerd. “All the venues were sold out as the audience in those days wanted to see the Star Club bands. The Rattles were something like the German Beatles, but we were more like the German Rolling Stones. The Liverbirds were the first ‘Girl Beat Band,’ so of course this was a very interesting bill. The time went really fast, it was like bus, tour, hotel, play.”

“We were really good friends with the Rattles and Liverbirds and there was never any conflict,” he continues. “We slept with the Liverbirds at the Hotel Pazifik in Hamburg, one of us with one of them to a bed—but nothing happened. We remain good friends to this day.”

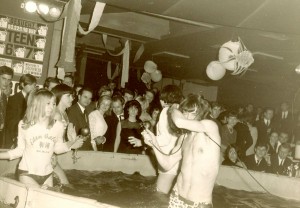

Reaction to the German Star Club bands was so vociferous that things sometimes got out of hand. “The Financial Office seized the till in Mainz,” recalls Olgerd. “The audience was very wild and stormed the stage. They let down iron bars, so we played behind bars and everything was fine.”

While the band’s wild stage act and Olgerd’s longhaired appearance went down well in Germany’s clubs and concert halls, out on the streets it sometimes provoked outright hostility. “One time, in Bielefeld, when I was alone, there were eight guys that wanted to beat me up because of my long hair,” he remembers. “I had no chance, but was a good runner and that way nothing happened to me. When we were together as a band, we never had any trouble as we of course looked very wild and dangerous.”

Over the years the wild and dangerous Brothers also took their act outside Germany’s borders to Vienna, Austria, the Star Club in Copenhagen, Denmark, and an American Army base in France.

More live recordings from the Star Club were released during 1965 and early ’66. “High Heel Sneakers” was included on Star Club Scene ’65 (Star Club, 1965), while the International Beat Festival LP (Star Club, 1966) featured three Phantom Brothers tracks, “Run Rudolph Run,” “Beautiful Delilah” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So” (the last a studio recording, the B-side of their first single). All the tracks—”Beautiful Delilah” in particular—are outstanding, hard-driving R&B performances, highlighted by edgy, aggressive guitars and walloping drums, the brittle German-accented vocals adding an additional edge to the proceedings.

In early 1966 the group made their first single, “Chicago” b/w “It Ain’t Necessarily So.” “The boss at the Star Club, Manfred Weissleder asked us if we wanted to finally make a single,” says Olgerd. “He asked [Rattles leader] Achim Reichel to write a song for us. He did, during the tour, and also produced the record.”

The single was recorded at a famous studio in Maschen, where the Rattles also recorded much of their output. “At the time we were very tight and together, so the two recordings were finished in just half a day,” recalls Olgerd. “Achim had wanted the song ‘Chicago’ a bit different but finally accepted our arrangement. He played the tambourine and harp on ‘Chicago’ and also sang the ‘hey hey’ back-ups, with others.”

Released on the Star Club label in early 1966, “Chicago” is a stone-cold classic, the catchy melody riding atop a crunchy Kinks-inspired riff and a riotous, fast-changing rhythm. The song’s shoutalong “Hey! Hey!” hook cements it as an unstoppable crowd-pleaser. Despite a disappointingly generic picture sleeve (using a photo of an anonymous band onstage at the Star Club instead of capitalizing on the Brothers’ distinctive image), the single is said to have sold an estimated 30,000 copies in Germany. It would have done even better had the band promoted it through TV appearances. The popular Beat Club show, filmed in Bremen, had done much to raise the visibility of German groups like the Rattles and the Lords, who regularly appeared alongside British and American acts on the show. The Phantom Brothers, though, blew their one big opportunity to get booked onto the show.

“Manfred Weissleder phoned Leckebusch, the boss of Beat Club and told him we were playing in Bremen and that he should come and see us live so that we could play on Beat Club,” recalls Olgerd. “The only problem was that the club we played at in Bremen, the Burger Landhaus, was bankrupt, and there was no audience there. So for fun we played a Viennese Waltz called ‘Wiener Blut’ [Vienna Blood] with adult-only content. At that very moment Leckebusch came into the room and, shocked by what he heard, quickly disappeared again. That’s why we never played Beat Club even though, with our status, we deserved to be there.”

Their no-show on Beat Club has also adversely affected the band’s posthumous reputation. When the show went into regular re-runs in the ’70s and ’80s, many of the ’60s era bands, such as the Rattles, the Lords, the Liverbirds and the Monks, found a new audience for their music. The Phantom Brothers however, were nowhere to be seen.

“Many people from the ’70s who never went to the Star Club [in the ’60s] because they were too young were later watching the Beat Club series,” says Olgerd. “They did not know of us because we never appeared on Beat Club. Recently a ’70s person said on an internet forum that he never saw us on Beat Club, and joked that ‘you just cannot see Phantoms’!”

The only TV appearances for the Phantom Brothers at the time were on news shows, reporting about the band’s wild stage show. By 1967 Olgerd was frequently stripping down to just his low-slung hipster trousers as he writhed around the stage like some bizarre genetic mutation of Phil May and Iggy Pop, the latter still a garage band nobody stuck behind a drum kit in suburban Michigan.

One widely reported stunt in 1967 found Olgerd at Berlin’s Playboy Club cavorting half-naked with go-go girls in an inflatable swimming pool. “The boss of the Playboy Club in Berlin, Rolf Eden, who was also the owner of several clubs in Berlin, hired us and we made ‘Beat In The Water’ with go-go girls,” explains Olgerd. “One of the girls was Ingrid Steeger, later star of the TV show Klimbim [and a household name in Germany]. We viewed this stunt more as a funny thing. The TV was also there and the German boxing star Prinz von Homburg threw me in the water and they broadcasted that.”

By this time the group’s repertoire had changed to include many soul numbers, like “Mustang Sally” and “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag,” and also some early Hendrix songs, including “The Wind Cries Mary” and “Purple Haze.” “Horst also started to sing and this was really good,” says Olgerd. “He sang ‘Purple Haze,’ ‘Soul Man,’ ‘Shotgun’ and ‘Gimme Some Lovin’. But we still played everything our way, with three guitars and with the original lineup, without sax or piano.”

“Until the end we had a hot stage show,” he continues. “Everyone was watching and no one was dancing. The show was still our old image and it got wilder. After half an hour all of us were really sweaty and we had to get changed and blow-dry our hair. I believe that the show was in those days very shocking and unique in Germany.”

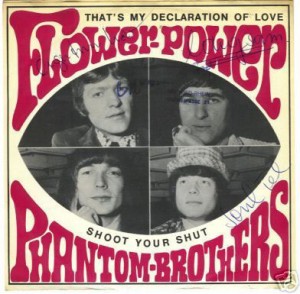

In late 1967 the Phantom Brother released their second and final single. Wolfgang sang lead on both the melodic “Flower Power” and its flipside, a stomping version of Junior Walker’s “Shoot Your Shot” (misspelled as “Shoot Your Shut”). Reportedly just 2,000 copies were pressed on the tiny ND/NC label. “When we stopped working at the Star Club—which slowly went bankrupt—we took a new manager, Rolf Treede. We produced a recording with him in the studio and created our own label ND/NC. This was the time of Flower Power, about a half a year after the hit ‘San Francisco.'”

By this time the once thriving German beat scene had begun to fade away and only the most popular bands, like the Rattles and the Lords, were able to adapt and survive. At the club level, DJs were taking over, and it was increasingly difficult for bands to get bookings. “Discos came up and bands died out,” laments Olgerd. “All the ’60s bands stopped playing because there was no more money to make and they needed money to live.”

The Brothers struggled on for another year or so, briefly adding a keyboard player to the line-up. “Bernd Schulz from Lueneburg, later with the Rattles, played with us for two weeks, more as a hobby,” says Olgerd. “We did not really want a piano man anyway, as we were a classic guitar band and stayed with that.”

Eventually Olgerd decided to quit the band. “This was in 1969 after a gig at the Astoria in Hamm, Westfalen,” he remembers. “Afterwards I became a DJ and made lots of money doing that. Rudi moved to Bielefeld where he got married and worked. He is and was the only real rocker among us, as he still played drums for a few decades in a rock band from Bielefeld. The other two, Horst and Wolfgang, took two others and played music by Vanilla Fudge for about one year after the split. Then it all came to an end. The show was missing.”

Olgerd later went into record production and had a million selling hit in 1978. “This was with the artist Luisa Fernandez, 16 years-old, and the hit was called ‘Lay Love On You.’ It was Number One in four European countries. I am living to this day off the royalties. In between I also ran a disco for three years.”

In his heart, though, Olgerd was always a Phantom Brother, and a few years ago he got the itch to reform the band. “After I met my life partner, Moni, I moved to Halle, Westfalen, close to Bielefeld, so I was closer to Rudi. I then had the urge to record our old sound again for a CD. Nowadays, Germany has a lot of Oldies shows again and the fans remember the great shows of the Phantom Brothers—the hardest beat sound in Germany at the time.”

“I eventually talked the others into it,” he continues, “which took a long time. We rehearsed in Rendsburg and Bielefeld and used a punk recording studio for our recordings.”

Recorded at Power Sound Studio in Bielefeld in late 2004, the Phantom Brothers’ Go Johnny Go CD is an authentic tribute to the band’s Star Club roots. Eight of the album’s nine songs are Chuck Berry numbers—including energetic versions of “Johnny B Goode,” “Sweet Little Rock’n’Roller” and “Oh Baby Doll”—and the other is a Bo Diddley song, “Before You Accuse Me.”

“You may be surprised that we play so many Chuck Berry songs on our new CD,” explains Olgerd. “We played all of those in the ’60s but we did not record them at the time. We wanted to go back to our roots and start fresh from there, where we left it. As you know, the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Angus Young and many others started with Berry and every band, including the Phantom Brothers, had their own style with this—almost garage-like. It was a ‘hot’ time between R’n’R and Sweet Beat [referring to the softer more melodic beat music that started coming up around 1965] and those who didn’t go to that earlier school were not aware of what it meant; they were not on the same page. If we release another CD we will not play as much Chuck Berry.”

On August 28, 2005, the band played their first show in 35 years in Buende, on a bill with Slade, Sweet and the Lords. The show was a great success, but, at the time of writing, the situation is uncertain. “Rudi and I want to continue, but the other two have problems again, including work related issues. With this the future of the band is not sure. However, Rudi and I will carry on as the Phantom Brothers, even if we have to bring in two other musicians.”

Whatever the case, the Phantom Brothers have already made their mark on German Beat history. As postwar refugee children living through uncertain times, they struggled against the odds, united and reunited as true rock’n’roll blood brothers, to make some of the hardest, wildest and most exciting sounds of a new and brighter era. For that we continue to salute them.

More info: www.phantom-brothers.de