-

Featured News

Shel Talmy: August 11, 1937 – November 14, 2024

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Sylvain Sylvain, 1951-2021: The Teenage News Checks Out

AN APPRECIATION BY TIM STEGALL

The current issue of Ugly Things contains a heartfelt tribute from Tim Stegall to New York Dolls guitarist Syl Sylvain, written in January after his passing. It unfortunately contained a factual error that could not be verified at the time of writing, pertaining to his birth name. The family and their representatives have confirmed his full name was Sylvain Sylvain Mizrahi. We apologize for any emotional distress and inconvenience this has caused the family. Here is the full obituary, corrected.

PARDON ME if I’m sentimental when we say goodbye. Don’t be angry with me should I cry. It ain’t often the likes of a Sylvain Sylvain—born Sylvain Sylvain Mizrahi in Cairo, Egypt, Valentine’s Day 1951—comes along. Which means when someone like Syl exits—as he did January 13 this year, following two years battling cancer—this big boppin’ world feels a whole lot emptier.

Of course, you can’t write about Syl without writing about the New York Dolls.

In 1980, Lester Bangs—the one rock critic (then) alive who wrote verbal rock ‘n’ roll—spent a benzadrine’d weekend pounding out Blondie, a quickie bio of New York punk’s first superstars. Published by Simon & Schuster’s rock division, Delilah, the thin book likely paid Lester’s rent for a couple of months. As with even Lester’s most crass efforts (as this surely was), there were flashes of genius. Such as the chapter “In Which Yet Another Pompous Blowhard Purports to Possess the True Meaning of Punk Rock,” the best three page summary yet written of punk—musically, culturally, aesthetically.

Which meant at least three or four of those paragraphs were some of the best writing ever about the New York Dolls.

“They might have taken some cues from the Stooges,” noted the pride of El Cajon, California, “but who they really wanted to be was an American garage band Rolling Stones. And that’s exactly what they were. Everything about them was pure outrage. And too live for the time — ‘72-3-4 mostly. They set New York on fire, but the rest of the country wasn’t ready for it.

“I was talking to a guitarist friend, and the subject of the Dolls came up.

“‘God,’ she said, ‘the first time they were on TV, we just couldn’t believe it, that anybody that shitty would be allowed to do that! How did they get away with it?’

“I felt like throwing her out of my house. They didn’t ‘get away’ with anything. They did what they could and what they wanted to do and out of the chaos emerged something magnificent, something that was so literally explosive with energy and joy and madness that it could not be held down by all your RULES of how this is supposed to be done! Because none of them are valid! Rock ‘n’ roll is about BREAKING the form, not ‘working within it.’ GIVE US SOME EQUAL TIME! Let the kid behind the wheel.”

I can remember one of those moments the Dolls were “lookin’ fine on television.” September 13, 1973, the day after my seventh birthday. Mom and Dad were at the Friday night kicker dance at the local VFW hall, in the tiny town where I grew up, Bishop, Texas. My teenage babysitter let me stay up with her to watch The Midnight Special, NBC’s popular televisual rock showcase of the age. It was always fun, especially when glitter rockers like Alice Cooper might appear, or old Fifties dudes like Little Richard.

I can’t remember who else appeared that night. But I remember the New York Dolls. I remembered them seven years later, when I picked up bargain bin copies of their Mercury albums after reading Sex Pistols interviews where the only bands they praised were the Dolls and the Stooges. I got it, the moment I heard “Personality Crisis.” There was the delinquent energy and the snot and venom I heard in the Pistols. And Johnny Thunders’ grimy guitar roar was clearly the square root of Steve Jones.

Then I realized this was that band that got me in trouble the day after that Midnight Special episode. I wandered into the kitchen as Mom washed dishes, wondering about this word my babysitter snarled at the TV screen as this band played.

“Mommy, what’s a faggot?”

I don’t think I’ve forgotten how nasty Palmolive tastes since.

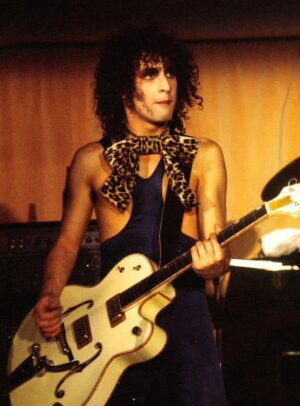

Nor, as stated above, have I forgotten what I saw that night with my babysitter. (Mind you, the clip is easily viewable on YouTube.) Maybe two minutes prior to the opening credits, Thunders ignited the opening guitar riff to “Personality Crisis” with a baby doll strapped to his back, all swagger, stacked heels and ultra-teased hair. David Johansen strutted like a Max Factor-ed Mick Jagger. Syl Sylvain and his Flying V guitar pirouetted in matching leopard trousers and oversized bow tie. The kids in the front row appeared shell shocked, save for two girls bopping at the stage’s lip.

Those cross legged James Taylor fans would never get it. The New York Dolls reinvented the ‘70s in that moment. What those boys on the floor didn’t know, those little girls did understand….

What nobody got then was how there’d have never been a New York Dolls without that bopping imp in the leopard spandex, with the corkscrew curls and that Flying V. Yeah, Johnny Thunders had the star power, charisma and raunchy guitar ethic that every future punk guitarist copied wholesale. But it was Sylvain Sylvain who taught Johnny how to do it.

“Basically, what we wanted out of music was something simple, powerful and sexy, topped with a hook that would just drive you crazy,” Sylvain told me in 1997, in an interview that ran in New York Dolls oral history “Doll Parts” for Guitar World magazine eight years later, as the band first reunited. “The Dolls’ music was mostly derived from ripping off the Rolling Stones and Eddie Cochran. We didn’t invent [the power chord], but we perfected it, and it became the punk sound. Instead of holding all six strings, you’re holding only two. But when you hit it hard and you’ve got your amp up loud, that’s what gives you the power. I showed that to Johnny, and I swear to God, he took that to the hilt. And that’s how we came up with every other song. ‘Chatterbox’ and the beginning of ‘Human Being’ were all power chords. It gave Johnny a brand-new invention. Of course, Marc Bolan [of T. Rex] used it and so did James Williamson from the Stooges.”

Syl Sylvain taught the Dolls all their dirty tricks. The name was his, derived from a walk past the New York Doll Hospital at 787 Lexington Ave while on lunch break at late Sixties Manhattan clothing shop Different Drum. Upon returning from a European business trip on behalf of his and original Dolls drummer Billy Murcia’s Truth & Soul clothing business, he found Thunders, Murcia, and bassist Arthur Kane rehearsing under the name that was his brainchild. Singing: Someone Syl’s pal Rodrigo Solomon introduced to him, David Johansen.

Management and Mercury seized upon Johansen and Thunders as the Dolls’ power duo. Producers were instructed to pay attention to them, downplaying crucial Sylvain compositions like “Trash” or the second album’s “Puss ‘n’ Boots.” But can you imagine either New York Dolls or Too Much Too Soon without them? And few get that Syl shared lead duties with Thunders on things like “Vietnamese Baby” and “Jet Boy.” He was a little bluesier, a little cleaner than his flashier friend. Later Sylvain classics like “Teenage News” became critical to the band’s Red Patent Leather endgame, before getting disseminated between David Johansen’s and Sylvain’s own solo records.

Now listen to Syl’s records. The Dolls’ mix of ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll, girl groups, and Stonesy raunch? That remained the core of solo Syl. He was the Dolls’ heart and soul.

I came to understand this as I got to know him the last 30-some-odd years of his life. I first met him and classic Dolls drummer Jerry Nolan on my first trip to NYC in 1988. They’d reunited under the name the Ugly Americans, playing a weekly residency at East Village raunch ‘n’ roll palace the Continental Club on Friday nights. It was the closest you’d get to seeing a Dolls reunion in those days. Years later, he was generous with his time, memories, and wisdom when I worked on that Guitar World piece. You could hear his pain at how the Dolls dissolved—that was his baby. You had to laugh at some of his DIY scams, like recording albums on a four-track, then dumping the mixes on cassettes, designing homemade covers, then sneaking them into the cassette sections of various New York record stores!

Mind you, I’d kill to hear some of those lost solo albums now. Bet you would too.

A few times, my bands the Hormones and Napalm Stars were privileged to open his shows. Those were always a master class in showmanship and raw rock ‘n’ roll. The main lesson I learned was that, for all the anger in punk’s DNA, the core of Syl Sylvain’s art was joy. He had his anger, certainly, especially when recounting how the New York Dolls broke up. But Syl Sylvain mostly wrote happy tunes, three chord celebrations. Onstage, he was overjoyed at playing this wild, primitive, yet deceptively well-crafted rock ‘n’ roll. This was a party.

And you never saw anyone happier when the New York Dolls finally reformed in 2004. The best tunes on those reunion albums? Syl Sylvain compositions like “Dance Like A Monkey.” He’d been the guardian of the Dolls’ spirit and legacy in those wilderness years in between, and he was ecstatic at being at the heart of their new lineup with Johansen and Kane, for the brief moment the latter could enjoy it before he died from leukemia. And no one was more heartbroken when the band dissolved for many of the same reasons that killed it off in 1975: Egos. The death of every great band. Of every great relationship, really.

So, it was back to Syl Sylvain to keep the band’s spirit alive again. David Johansen had returned to his Buster Poindexter alter ego. In 2017, Syl came to Austin to play a weekly residency at hipster garage room Hotel Vegas, backed by a local punk supergroup calling themselves the Sylvains. The Hormones were overjoyed to be handpicked to open one of the shows, of course.

The afternoon of our gig, I called my old friend, who had become my “Uncle Syl” by this point. “You’re family now, Tim,” he told me after I’d worked as the Dolls’ guitar tech one SXSW weekend. “Listen to what your Uncle Syl tells you, now!” And now I was calling him where he was staying.

“Syl,” I began, “y’know that since the Dolls broke up, we’ve been playing ‘Personality Crisis,’ we’ve been playing your song ‘Teenage News,’ we’ve been playing some of Johnny’s songs. We don’t want the Dolls to die. Would you like us to lay off those songs in deference to you tonight?”

“Are you kidding?!” he roared. “I am so fucking proud of you for playing those songs! You are keeping the spirit and music alive! I want you to play every one of those fucking songs tonight!”

We did. The crowd went apeshit. Then he came on and showed us the right way to play them. With all the joy of having invented everything we all love about punk rock. Now it’s up to all of us still standing to carry it on. Uncle Syl, I weep as I finish typing these lines. We have lost a lot with your passing. That will never be replaced or equalled. Thank you for the rock ‘n’ roll. Thank you for punk rock. Thank you for the New York Dolls.

Thank you for having been Sylvain Sylvain. Sleep, Baby Doll. Sleep.