-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers -

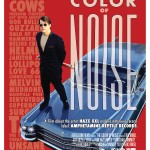

THE COLOR OF NOISE (MVD Visual/Robellion Films) Blu-ray/DVD combo

By Doug Sheppard

The combination of an unbearable mainstream and inadequate underground made the ’80s the worst decade of the rock ’n’ roll era. Hardcore, postpunk and thrash metal played out quickly as MTV, radio and major labels spattered the manure of crass, overproduced corporate music awash in synthesizers and obnoxious loud drums. Worse, conformity that rejected the ’60s counterculture pervaded throughout society, giving rise to religious fanatics and other ignoramuses (e.g., the PMRC) who sought to censor what little truly alternative sounds were out there.

If you didn’t fancy derivative, wimpy college rock that rocked only slightly more than Peter, Paul and Mary, there wasn’t much — and by the late ’80s, there was virtually nothing. Punk and metal were mostly clichés, the garage revival was going nowhere, and rock ’n’ roll in general lay dormant. Into this late ’80s void came a louder, noisier underground as heard on new labels like Sub Pop and Amphetamine Reptile.

The story of Sub Pop is well known, but Amphetamine Reptile went undocumented — until now. The Color of Noise tells the story of a label that was essentially Sub Pop’s evil twin: rawer, ruder, darker and more provocative — yet almost as influential in making the 1990s better than the 1980s and helping lay the groundwork for the future.

Amphetamine Reptile (named after a slight mishearing of Motörhead’s “Love Me Like a Reptile”) reflected the ambitions of its owner, Tom Hazelmyer, a guitarist and veteran of such Minneapolis bands as Todlachen and Otto’s Chemical Lounge — not to mention the US Marines — who founded the label to put out records by his noise rock combo, Halo of Flies.

Like Sub Pop after its humble beginnings, Hazelmyer soon found an audience of dissatisfied youth ready to embrace his iconoclasm. His label signed more likeminded noise rockers like the Cows, God Bullies, Unsane, Boss Hog and the band that put AmRep on the map, Helmet. As the releases and European tours for AmRep acts mushroomed, so did the imprint’s rep for provocative artwork (by renowned artists like Frank Kozik, Coop and Derek Hess) and uncompromising DIY ethos. If the ugliness and outrage of AmRep bands reflected distaste for the ’80s itself, who could blame them?

Hazelmyer himself and every AmRep band of significance is interviewed, as are sleeve artists, label employees and outside observers like Jello Biafra. The Color of Noise serves as much as a bio of Hazelmyer — also a restaurateur and print artist — as it does the story of his label, but that makes sense, as the two are inextricably linked. The cinematography is first-rate, interspersing quality old clips of AmRep bands in various clubs worldwide with colorful presentations of flyers and sleeves and, of course, interviews with the provocateurs who shared Hazelmyer’s vision.

The parallels to Sub Pop are striking. Both hailed from cities — Seattle and Minneapolis — that produced some of the greatest local rock scenes of the ’60s. The labels not only did joint releases, but saw overlap in bands that recorded for both. And just as Sub Pop went big with the rise of Nirvana, Helmet’s ascent to platinum status with Meantime in 1992 ensured that AmRep (which then sold Interscope Helmet’s debut, Strap It On) would be a viable business proposition for years to come.

Or at least until 1998, when Amphetamine Reptile went dormant — with only sporadic releases since. But even if it didn’t last as long as Sub Pop, which continues to this day, its influence is almost as significant. The 1991 revolution that turned many heads in the direction of alternative sounds was mostly spurred by Nirvana, but Helmet — and therefore AmRep — was also part of the mix. Doom metal, stoner metal, garage rock and the psychedelic revival all existed before then, but undoubtedly got a boost when, yes, the alternative briefly became the mainstream and told impressionable teens that there was something else out there.

Today’s mainstream might be worse than ever, but the underground is healthy. We owe Amphetamine Reptile and other vintage indie labels gratitude for laying — or at least strengthening — the groundwork when bands didn’t have the reach and immediacy of the Internet. And we have The Color of Noise to thank for preserving an interesting piece of rock ’n’ roll history in this fine documentary.

What’s Missing in Music Bios? Often What’s Great About the Music

By Bill Wasserzieher

The problem with many documentaries about solo artists and/or bands is that they “print the legend,” to lift that old line from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. That is, filmmakers, being storytellers, flesh out the accepted version of their subject’s career—and that’s good for what it is, overviews being useful for the uninitiated—but rarely do they dive deep for what is at the core of the actual art.

To put it another way, is there even one among the scores of Dylan documentaries that digs into his songwriting process? I’d love for the hire-by-the-hour “talking heads” who pop up in them to focus on the creative vision that, for example, produced “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.” Think about those opening lines:

When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez and it’s Easter-time too, And your gravity fails and negativity don’t pull you through, Don’t put on any airs when you’re down on Rue Morgue Avenue, They got some hungry women and they’ll really make a mess out of you.These are maybe the bleakest lines since T.S. Eliot was ruminating on “The Hollow Men” and “The Wasteland.” But, no, we always hear about young Bob scuffling in the Village, courting Joan Baez, going electric, retreating to Woodstock, finding/losing/finding religion, ad infinitum. Instead, tell me about those carbolic lines and how his etched-with-acid voice shoves them to the gut.

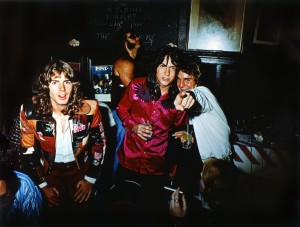

Jody Stephens, Andy Hummel and Alex Chilton. (Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures. Photo credit: William Eggleston, Eggleston Artistic Trust)

This problem comes to mind with the new and very competently made documentary Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me (Magnolia Pictures). The filmmakers present nearly a two-hour overview of a band whose members were young white guys from Memphis—one a former teenage hit-maker with the Box Tops—who cut an indisputably great album, #1 Record, that went unnoticed; followed by another, Radio City, nearly as good and equally ignored; and then a third, Sister Lovers, which was never actually finished, as the players drifted off to different and mostly sad, bad fates.

The filmmakers get the Big Star story from the band drummer Jody Stephens and bassist Andy Hummel, from friends and relatives of deceased members Chris Bell and Alex Chilton, their Ardent recording studio associates (Ardent headman John Fry is the film’s executive producer), an array of rock critics (including a funky old Lester Bangs clip), plus numerous praise-wielding musicians, among them Jim Dickinson, Chris Stamey, Mike Mills, Robyn Hitchcock and Ken Stringfellow.

No denying it’s a well-crafted overview, but what’s missing is serious analysis of the songs and the musicianship on No. 1 Record. What are those songs about? What do say about life as Chris Bell and Alex Chilton were experiencing it, their individual and sometimes at war psyches (Bell bipolar and troubled by sexual identity issues, Chilton bitter, caustic, frequently loaded), and how did their minds and voices work together and separately? These are things crucial to the Big Star story. Otherwise the band was just one of millions that arguably could have been the new Beatles but were not, though at least this one became famous after the fact and served as a fountainhead for power-pop bands that came later.

Plus the documentary, while keeping with the legend, plays it cautious. Nowhere is the Alex Chilton I met a few times, first in New York City during the late 1970s when he had a loose ensemble called the Cossacks. One night I asked him about the Big Star records, and he responded, “Fuck that old shit.” Nearly 25 years later, after he and Jody Stephens reformed Big Star with members of The Posies, I cornered him after a solo show at McCabe’s in Santa Monica, where he had intentionally bummed out a capacity crowd hoping to hear a few Big Star and/or Box Tops tunes by playing instead “Volare” (“Nel blu dip into di blu”) and other songs better suited to a Dean Martin tribute. I asked him why, and he said, “I hate my fans.” Sometimes an artist is his own worst enemy, but Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me doesn’t say so.

And that brings to mind those purveyors of commercial/corporate rock, the Eagles. At least the documentary History of the Eagles manages to do more than provide the standard career recap. Glenn Frey, the film’s executive producer and primary talking head, spends three hours trashing everyone who has ever rubbed him wrong—producer Glyn Johns who got the Eagles their first hits, former bandmates Bernie Leadon and Randy Meisner (whose previous stints in Dillard & Clark, the Flying Burrito Bros. and Poco gave the Eagles early credibility), original manager and label boss David Geffen, even Timothy B. Schmit and Joe Walsh who are still contracted sidemen in the band, and especially Don Felder who is reduced to tears when interviewed on how he came to be kicked out.

According to Frey, only he and Don Henley really matter in the grand scheme of things—and that’s why he’s proud to say they get bigger bucks than the others, money apparently his ultimate gauge for success. At no time does Frey ever seem to see beyond his own ego, coming off as vengeful, arrogant and self-absorbed. It’s fascinating and twisted, as creepy as watching footage of performance artist Chris Burden nail himself to the hood of a VW Beatle. But at least it’s more than just another example of “print the legend,” and we do learn something about his band’s songcraft, including that Frey dreamed up the title “Life in the Fast Lane” while roaring through Hollywood at 90 mph in a Corvette driven by his dope dealer on their way to a poker game.

In issue #36 of Ugly Things, Alan Bisbort has a review of a DVD titled A Band Called Death. Comprised of three African-American brothers from Detroit who played rock rather than Motown, the band was good enough for Clive Davis, then the head of Columbia Records, to offer to sign them if they would change their name to something less of a sales-killer than Death. But they wouldn’t, so he didn’t. Now that’s a legend new for the telling. Also, for a more detailed review of Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, see Jon Kanis’ piece in the same new issue.