-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

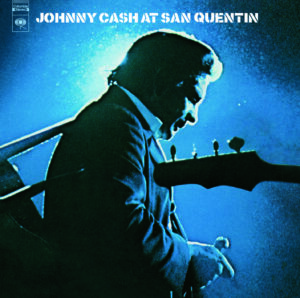

Johnny Cash: Live at San Quentin returns and a 1975 interview

By Harvey Kubernik

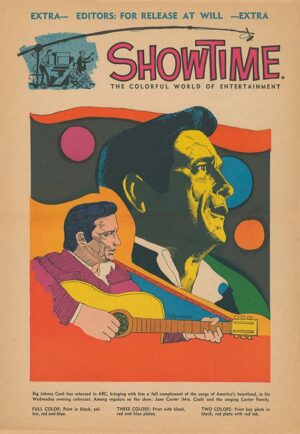

Amazon Prime and the Coda Collection are launching a new company programming rare concerts and music documentaries, along with exclusive premieres for films and music documentaries. The Prime Video channel debuts February 18, 2021 and during 2021 Amazon Prime members will be able to access dozens of their library acquisitions exclusively streamed in the US. Some of their first titles announced for broadcast are the streaming premieres of The Rolling Stones On The Air, Music, Money, Madness…Jimi Hendrix in Maui, and Johnny Cash at San Quentin.

I thought it was appropriate to examine the Johnny Cash Live At San Quentin album that celebrates its 52nd retail anniversary on February 24. Johnny and I share a February 26 birthday.

In 1965 I saw a Cash Shindig! taping on Prospect Avenue in Los Angeles at ABC-TV studios, and in 1968 when he guested on The Summer Smothers Brothers Show at CBS Television City. I later caught Johnny and June Cash at The Anaheim Convention Center, The Troubadour and The House of Blues in Hollywood. I must have seen their act over a dozen times in 25 years.

“A Boy Named Sue,” written by humorist, poet, and singer/songwriter Shel Silverstein became a popular hit record during 1969 by Johnny Cash. On February 24, 1969, two days before he turned 37, Cash recorded the song live in concert at California’s San Quentin State Prison for his Johnny Cash At San Quentin album produced by Bob Johnston, issued on Columbia Records June 26, 1969.

Born Sheldon Allan “Shel” Silverstein in Chicago in 1930, Silverstein was known for his cartoons, songs, children’s books and contributions to Playboy magazine.

During 1969 Silverstein’s own recording of “Boy Named Sue,” a 45 RPM on the LP Boy Named Sue (And His other Country Songs), was produced by Chet Atkins and Felton Jarvis.

It has been said that Silverstein’s inspiration for the song’s title came from a man named Sue K. Hicks, who was a judge in the state of Tennessee. Silverstein heard Hicks speak at an event, and was intrigued by the name of Sue for a man. Apparently it was the father of Sue Hicks who named the boy after his mother, Susanna Hicks, who died during hospital birth.

Legend has it that Silverstein had penned the tune after a conversation with his friend Jean Shepherd, the writer, radio and television storyteller, who remarked about his own childhood dismay at being taunted for what many kids felt was a “girl’s name.”

Silverstein first introduced his copyright to Johnny and June Cash during a “Guitar Pull” at their Hendersonville, Tennessee home where local and visiting musicians would pass a guitar around and play their recent songs.

Mitch Myers, Silverstein’s nephew, biographer, and Director of the Silverstein archives, emailed me in 2018 verifying that it was June Carter Cash who encouraged Johnny to include it in their stage show.

Canadian-based writer and Cash scholar Gary Pig Gold, in the September 11, 2009 Rock and Roll Report also provides additional information on how “A Boy Named Sue” landed in the Cash repertoire: “It was quite common for JC to invite special televised Johnny Cash Show guests back to his grand new Hendersonville, TN homestead for post-taping song swaps. On any such evening the guitar would be passed round to, for example, Graham Nash (who offered ‘Marrakesh Express’), Kris Kristofferson (premiering ‘Me And Bobby McGee’), and of course Johnny’s ol’ pal the Zimmer Man (who, applying his grand new boudoir voice, crooned ‘Lay Lady Lay’).

“In fact one morning after, a young Rosanne Cash was flabbergasted to find none other than her teenage bedroom wall pin-up prince Davy Jones sitting at the breakfast table! (Yes, Johnny had hosted the Monkees on prime time just the night before).

“One most momentous evening however, the inimitable Shel Silverstein decided to test-drive a peculiar—even by Silverstein standards—new number he hadn’t even considered shopping across Music City just yet. Johnny wanted to hear it though:

“That’s the most cleverly written song I’ve ever heard” was the verdict minutes later, and luckily June thought enough to stuff Shel’s cheat sheet into her husband’s bag before they departed for the next day’s recording session over at San Quentin. “I didn’t even know the lyrics,” Johnny recalled of making his quickest, biggest hit. ‘I had to put the words on a music stand in front of me. I told ’em I wanted to sing a song called ‘A Boy Named Sue.’ Well they laughed, you know, and I said ‘No, it’s not what you think. Let me sing it to you.’ I read the lyrics off the paper in front of me, and that was the record.’

“And by late that summer, only those Rolling Stones and their honky tonk women could keep Sue off the very top of your local Top 40 Radio survey.”

Cash wrote in his autobiography Man In Black, that he had just received the song and only read over it a couple of times. It was incorporated in the prison concert just to try it out. On the filmed documentary of the event Johnny can be seen regularly referring to the paper lyric sheet.

Cash biographer, Robert Hilburn, JOHNNY CASH: The Life (Little, Brown and Company) confirmed as well that neither the British television crew filming the concert as well as his band knew he planned to include the song in his act while Carl Perkins and the musicians improvised backing on the spot.

The recording contained the lyric “I’m the son of a bitch that named you Sue!” It was subsequently edited out in the first product shipments on the single and the Johnny Cash At San Quentin album. On subsequent re-orders, compilations and reissues, “son of a bitch” was modified to “son of a gun” or even bleeped out completely on some configurations for AM and FM radio airplay.

The live San Quentin version of the song became Cash’s biggest hit on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and his only top ten single there, spending three weeks at #2 in 1969.

“A Boy Named Sue” topped the Billboard Hot Country Songs on September 16, 1969 and radio station KHJ in the Los Angeles market on their August 6, 1969 radio station survey. Cash’s unplanned smash hit record was certified Gold by the RIAA on August 14, 1969. It also earned a Grammy for Silverstein in 1970 as best Country & Western Song.

Originally a single album, this century Johnny Cash At San Quentin is now a deluxe three-disc, Legacy Edition package: two CDs containing 31 selections, 13 of them previously unissued. The package also houses a DVD, Johnny Cash In San Quentin, the culture-shaping 1969 documentary produced and directed by Mike Darlow for England’s Granada television network. Journalist Geoffrey Cannon from The Guardian had pitched the idea to executives at Granada and eventually sold the concept to Cash’s manager, Saul Holiff.

The expanded Johnny Cash At San Quentin includes a full rendition of “A Boy Named Sue.” It’s a stirring portrait of Cash and band; the Statler brothers, lead guitarists Bob Wooten and Carl Perkins, bassist Marshall Grant, drummer WS Holland, June Carter and Carter family members. There are also interviews with the prisoners and guards who were in attendance when The Johnny Cash Show packed the big house.

Shel Silverstein’s tune and the fortuitous alignment with Johnny Cash has continued for half a century in magazines, movies and informed other songs by bands referencing it.

A 1970 issue of MAD magazine displayed a parody titled A Boy Named Lassie. A male character in the movie Swingers is named Sue, and another actor announced on screen, “His dad was a big Johnny Cash fan.”

It was in June 1967 when Columbia Records staff producer Bob Johnston replaced Don Law at the Nashville based company producing Cash. Johnston’s production acumen and label machinations on behalf of Cash in the 1968 and ’69 time period resulted in two California penitentiary location-created live recordings: Johnny Cash at San Quentin and Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison.

Johnston’s credits include Leonard Cohen’s Songs From a Room and Songs of Love and Hate, and Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde, John Wesley Harding, and Nashville Skyline. He worked on Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends.

Johnston was born in 1932 in Hillsboro, Texas. His career began as a songwriter eventually holding a staff writing position at Elvis Presley’s Hill & Range Music and often reviewed potential Presley demos and songs earmarked for his movies in 1964 and 1965. Bob co-wrote with Charlie Daniels “It Hurts Me,” the flipside of Presley’s hit “Kissin Cousins” before he joined Columbia Records in 1965.

I met Johnston and producer/label executive Jimmy Bowen in July 1978 at MCA Records on Lankershim Boulevard in Universal City when I was West Coast Director of A&R for the label. At the time Johnston was producing Joe Ely’s Down on the Drag. We went down the street to see Ely at the Palomino Club.

“When I took over Cash he didn’t hit the country charts,” declared Johnston in a 2007 interview with me. “Like I said on the back of the Folsom Prison album liner notes, no one for eight years would let him go there to record live until he got me, and I said, ‘let’s do it’ I picked up the phone and called Folsom and San Quentin,” Bob remembered.

“The reason the Folsom album was made first is because the Folsom warden answered first, simple as that. I got the warden, Duffy, and I handed Johnny the telephone and left. When we did Folsom there was a guy who was going to introduce Johnny on stage in front of the cons and everyone standing up.

“I said ‘bullshit!’ And told Johnny to go walk out there now! They are not even sitting down good. Walk out there and jerk your head around and say, ‘Hello. I’m Johnny Cash’ and it don’t matter what the fuck you record. And he said ‘Get outta my goddamn way!’ And he didn’t usually cuss. But he pushed people away went out there and the goddamn place became unglued!

“I had the engineer Neil Wilburn, did the Cash Live At Folsom Prison album with him. And he was a genius behind all that shit. I had a great thing with anybody who was a genius!

“Leonard was the best I’d ever heard. And Dylan was the best I’d ever heard. Simon was the best I’d ever heard and Cash was the best I’d ever heard. And all those fuckin’ people were the best I’d ever heard.

“I’ll tell you something else I did recording Dylan, Cash and Cohen,” emphasized Johnston. “Everybody else (at the time) was using one microphone. What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I would use the echo. I could do that as much as I wanted. I wanted it to sound better than anything else sounded ever, and I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it. And that’s the way that we did it. I always had four or eight speakers all over the room and I had ‘em going. The louder I played it the better it sounded to me.

“I had Cash in the Columbia Music Row studio [February 1969] and thought it would be nice to get Dylan in there, too and I didn’t say anything to them. Cash was in the studio and Dylan came in. ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘Gonna record.’ ‘Well, I’m recording too.’

“So, they invited me to dinner, but I said ‘no thanks.’ And when they returned I had a café set up outside with microphones and their guitars, and they came in for two hours, like a nightclub, looked at the lights, sorta smiled at each other. June Carter Cash was there. We did like 18 tracks.”

The session yielded the duet “Girl from the North Country,” only heard on Nashville Skyline.

“I spent a lot of time with Bob Johnston and I believe he deserves an enormous amount of credit for the Folsom Prison album and some of the other albums he did with John,” Robert Hilburn pointed out to me in our 2016 interview. “He not only helped John believe in himself at a time when the drugs and other problems had left him vulnerable, but he organized the Folsom tracks and San Quentin tracks in a way that maximized their impact.”

These live Cash albums each reached triple platinum awards in the United States. Johnny Cash At San Quentin was his only # 1 LP in his lifetime.

Working with Columbia producers Don Law (1958-67), Frank Jones (1960-67), Bob Johnston (1968-70), Larry Butler (1972-78), Charlie Bragg (1972-77), Brian Ahern, Billy Sherrill, Chips Moman, and others, Johnny Cash was always in command of his direction, whether it was country and western, gospel, blues, rockabilly, traditional balladry and folk, or any other style he chose to pursue.

Bob Dylan’s relocation to Nashville to record Blonde On Blonde in 1966 with Johnston, along with the established presence of Johnny Cash on the Columbia label created an impulsive career decision for the soon-to-be-turned songwriter, Kris Kristofferson, who studied creative writing at Pomona College in Southern California and earned a Rhodes scholarship to study literature at Oxford.

I discussed this with Kristofferson in 2010 when I worked as the Consulting Producer on director Morgan Neville’s Troubadours: The Rise of the Singer-Songwriters.

Around the Dylan/Johnston Blonde On Blonde sessions, Kristofferson was working as a janitor sweeping up floors and cleaning up ash trays at the Nashville CBS studios and forbidden to pitch songs to company clients. Although when he met June Carter on the premises he asked her to give Johnny Cash a tape of his. June did, but Johnny tossed it on a large pile of other submissions.

Kristofferson briefly served in the Tennessee National Guard and still had his commercial pilot’s license from his previous job in Lafayette Louisiana at a company Petroleum Helicopters International.

Kris then spoke of a strategic maneuver of his flying a helicopter over the Cash residence and dropping a demonstration tape on Johnny and June’s house lawn in Tennessee. “I flew in to John and June’s property and almost landed on their roof. Looking back, when I think about it now, I could have been arrested or court-martialed,” he sighed to me one afternoon around a taping inside the empty Doug Weston Troubadour club in West Hollywood.

In 1966, Johnny Cash was just concluding his own geographical relationship to the Southern California area and Los Angeles.

Before he became a living tradition, Johnny Cash spent large portions of a decade of his life near planet Hollywood after leaving Sun Records and Memphis, doing his first gospel LP when he signed to Columbia Records.

On August 13, 1957 at a party in California, Cash first met British-born record producer Don Law after a local television date who first touted Johnny about joining Columbia Records after Cash’s contract with Sam Phillips and Sun ended on August 1, 1958. That same month Cash and clan moved to California and he rented an apartment on Coldwater Canyon Avenue in North Hollywood.

Cash and his family later bought a ranch house from comedian/TV host Johnny Carson on Havenhurst Avenue in Encino in the San Fernando Valley. Johnny Cash Enterprises was located on Sunset Boulevard at the Crossroads of the World complex in Hollywood.

He did a slew of television appearances in the Southern California area in the sixties including the Compton-based and Hadley’s Furniture sponsored Town Hall Party program in 1960 that was broadcast on KTTV-TV. In 1961 Johnny came to Pal Records on Sherman Way in Canoga Park for an autograph party.

Cash, and his pal, actor, singer and radio host, Johnny Western, along with Pat Shields, a PR guy doing promotions for Liberty Records, had a company together called Great Western Enterprises on Western Avenue in Hollywood.

In 1964 Cash recorded Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian, his history of Native Americans concept album. He toured Wounded Knee, South Dakota with descendants of the survivors of the 1890 massacre, played songs from the LP at a benefit performance at Cemetery Hill for the tribe and helped the Sioux raise money for schools. This is four years before AIM, the American Indian Movement civil rights organization was founded in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Cash sent out personal letters and copies of his 45RPM recording of folksinger Peter La Farge’s “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” on that album, after Johnny purchased a thousand of them from Columbia Records and mailed the entire batch to every radio station in the country. It eventually landed at number three on the Billboard Country Singles chart in 1964.

In February 1965, Cash performed “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” on a Los Angeles television program, The Les Crane Show.

When Johnny Cash died in 2003, writer Todd Everett informed me about a 1964 Ventura College Gymnasium benefit Cash did for the police department, “‘cause Johnny was always getting in trouble in an area between Ventura County and Ojai California, his young girls with his first wife Vivian (Liberto) grew up there. And Johnny purchased his father a trailer home. And if that ain’t country you can kiss my ass.”

“John had some happy years in Encino, but gradually things started going bad,” Hilburn detailed in our 2016 interview. “His film debut—in a low budget crime story called Five Minutes to Live—was embarrassing, a real disaster. And tensions developed between John and his wife, Vivian, over the career demands that took him away from home so often. Then, the drugs took hold.

“Looking for a new start, he moved to a small town in Ventura County to escape the glare and pressure of Hollywood. But the tensions and drugs continued. He pretty much stopped coming home. By early 1966, he had pretty much left California and the family behind. He moved to Nashville and spent most of his time with June Carter.

“One of the big reasons John left Sam Phillips for Columbia was he wanted artistic freedom, which is something Columbia promised—and it eventually came back to haunt the label because they wanted hits and that wasn’t the primary thing on John’s mind.

“Again, he wanted to make music that lifted people up—music that reflected his fascination with people and their struggles; hence so many songs about the Old West and the working man and Native Americans. John wanted to make music that mattered to him; Columbia wanted hits. The issue came to a head in 1963 when his Columbia contract was due to expire. Columbia was going to drop him, but Don Law, who signed John and produced his records, talked them into one more session. They came up with ‘Ring of Fire’ and Columbia did renew the contract. If he hadn’t come up with a hit in that session, Columbia, in fact, would have dropped Johnny Cash.

“At the time Cash was making concept albums like Ride This Train and Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian in the 1960s, the country music world (chiefly radio) was focused on hits. They weren’t looking for ‘art’ from their singers. But rock ‘n’ roll changed that. Thanks to people like Dylan and the Beatles, fans began to look for ‘art’ as well as ‘hits’ and they began buying albums rather than just singles. Cash tapped into that with the Folsom Prison album, and he found an audience that didn’t just listen to country radio. He was embraced by the rock culture, and I think it’s that audience finally discovered Cash’s ‘art’/concept albums.”

On August 16, 1975 forty miles from Los Angeles, California, I interviewed Johnny Cash for the now defunct Melody Maker inside the Royal Inn Hotel in Anaheim. At the time of our interview Johnny was in town in 1975 to promote his autobiography, Man In Black, and to perform a special concert for the Christian Booksellers convention.

“It covers the ups and downs of my life and music career and my problem with drugs,” stressed Cash. “The book also contains 20 song lyrics which provide a musical guideline. The lyrics help tell the story. It was time to do the book and set the record straight. About a year ago I was approached by the publisher to write it. I spent nine months writing it and shaping it. I wrote it by hand and worked with an editor.

“It was a whole new project for me. More discipline was involved. It was my main activity for months when I got up in the morning. It was hard lookin’ back through my life and trying to remember conversations and details. Remembering some of the nightmares that I had especially gettin’ off drugs. I went through a total soul-searching experience lookin’ back. I went through all the pain again to a certain degree,” Johnny confessed.

The book eventually sold over a million copies.

“In concert I sing ‘Sunday Morning Coming Down,’ the Kris Kristofferson tune. That’s so much of me that sometimes I feel like I wrote it. There are some songs that I must write for self-expression. If a song comes along I must acknowledge it. I’ve recently recorded a song ‘Strawberry Shortcake.’ It’s about a guy who went into the Plaza hotel in New York and stole a cake. It’s a novelty song. But there are some songs that I had to write like ‘I Walk the Line’.”

In the late ‘60s Cash was selling concert tickets and guesting on TV. The success of his Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison long player gave him new visibility on the pop and rock charts.

Then an American television documentary Johnny Cash! The Man, His World, His Music, directed by filmmaker Robert Elfstrom had a US TV premier in March 1969. Johnny and June Cash, the entire Carter family, Bob Dylan, Bob Johnston, Marshall Grant, Merle Kilgore, and Bob Wooton received vital US TV exposure.

This landmark screen gem, coupled with the ’69 UK-shown Granada-TV Johnny Cash At San Quentin documentary, resulted in ABC-TV offering manager Saul Holiff on behalf of Johnny, an hour-long pilot as a 13-week summer replacement for their Saturday night variety show, The Hollywood Palace.

In June 1969, Columbia Records issued Johnny Cash at San Quentin that hit the sales charts, aided by the LP’s smash country and pop hit single “A Boy Named Sue.” It convinced the ABC network, who then picked up his option for a full season which was conceived, developed, directed and executive produced by William Carruthers. Stan Jacobson was the producer and associate producer was Joel Stein.

Bill Carruthers had previously directed The Soupy Sales Show on station WXYZ-TV in Detroit and had directed the Ernie Kovacs game show Take a Good Look, for ABC-TV. Carruthers subsequently directed The Newlywed Game and The Dating Game.

“Dylan called my dad before he and the staff left for Nashville,” recounted Byl Carruthers, then Billy, the son of William Carruthers. “I had gone to work with my dad that day. He had an overall deal with Screen Gems at the time, and had an office on their lot. He had said we were going to get lunch, and then his assistant beckoned him back to the office, saying it was important!

“Two full hours went by, and I had to wait. When he got off the phone, he came out and said that he had just gotten off the phone with Bob Dylan. I asked him what he was calling about, and he said that Johnny wanted Dylan to do the show. Johnny really wanted Bob to do the first episode, and told Bob that he would be in good hands with my dad, and he wouldn’t have to do anything he didn’t want to. My dad said Bob was ‘feeling him out’ on the phone.

“My dad was very cool about letting me hang when the musicians were there, and yes, I got to fetch coffee and stuff for Bob Dylan, in the hour or so before the taping…

“I distinctly remember Dylan having two very sedate western-style two-piece suits laid out, and he saying to my dad, ‘Bill, which one of these do you think would be best?’ A few minutes later, my dad said to the assistant director, ‘I can’t believe Bob asked me what he should wear!’

“The first show was a mindblower, as we all know, and the first season surprised ABC enough to pick it up. The sets were cheap, ‘cause they had no money. The production issues they faced retro-fitting the Ryman Auditorium were immense,” recollected guitarist/songwriter Carruthers, now in the roots music duo, Café R&B.

“For that year of pre-production and production, my dad and John were close. He showered my dad with gifts (among them a 1932 Martin Guitar, and a Civil War Colt Pistol—John had a pair of them with consecutive numbers. He gave my father one, and he kept one, so they’d each have one as symbol of their relationship). My dad was the executive producer and director for the first year. It was his show.”

During 1970-1971 the prime time Cash slot was then helmed by Jacobson. A veteran of The Wayne and Shuster Show for several seasons, Jacobson had been a writer for Country Hoedown and writer/producer of the program Music Hop. In 1966 he wrote and directed the Battle of Britain documentary for the Canadian Broadcasting Company series Telescope, and in 1967, The Legend of Johnny Cash.

“I would say there were many things that likely would not have happened were it not for [manager] Saul Holiff’s influence on Johnny’s career, but the San Quentin show and Johnny’s television show are both ones that undoubtedly can be credited to Saul’s vision for Johnny,” observed author Julie Chadwick who wrote The Man Who Carried Cash: Saul Holiff, Johnny Cash and the Making of an American Icon.

“On the television front, there are dozens of letters that go back more than a decade in which he continually pitched the idea of getting Johnny on TV, which finally bore fruit when a Canadian named Stan Jacobson decided to do a CBC special on Johnny in 1967, which many regard as the predecessor to his television series.”

The Johnny Cash Show debuted in June 1969. Programs were done at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, which back then was home to the Grand Ole Opry 1943-1974. Bill Walker was the musical director and arranger. June Carter Cash and the Carter Family, Carl Perkins, The Statler Brothers, and The Tennessee Three were screen regulars. Fifty-eight episodes were originally broadcast from June 7, 1969 to March 31, 1971.

Among the Cash-invited performers: Louis Armstrong, Bill Monroe, Dusty Springfield, Judy Collins, the Monkees, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Stevie Wonder, Tony Joe White, Homer & Jethro, the Everly Brothers, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Derek & the Dominos, Roger Miller, Faron Young, Charley Pride, Loretta Lynn, Marty Robbins, Mickey Newbury, Neil Diamond, Conway Twitty, Tammy Wynette, Bob Dylan, Waylon Jennings, George Jones and Doug Kershaw.

In 1975, Johnny and I chatted in Melody Maker about his groundbreaking 1969-1971 The Johnny Cash Show. In 1970 it reached #17 in the Nielsen ratings. That year, Columbia Records shipped The Johnny Cash Show, a live album, coinciding with the TV series, which was not promoted to retailers as a soundtrack. The LP is an unusual product as the Columbia label was not affiliated with the competing CBS-TV network. I am the proud owner of a white label Columbia Records Radio Station Service Not For Sale promotional copy.

Cash’s variety show TV program, along with his successful Folsom Prison and San Quentin albums ushered in today’s acceptance of country music artists on national and cable television.

“One reason country music has expanded the way it has is that we haven’t let ourselves become locked into any category. We do what we feel,” ventured Cash.

“I like to go into the studio with my own musicians and record my own songs,” Johnny reminded me in our encounter. “I’m open to other songwriters. I like to do things differently all my career.”

However, Johnny said that TV obligations hampered his creativity. “It cut down on my touring, it became too confining. We stayed in Nashville for two-thirds of the time. I really didn’t enjoy it all that much. If it was kept loose and spontaneous it could have been great. But we had to do the same song every eight or ten times before they would accept it. The show lost its feel and honesty. Consequently I lost a lot of interest in it.”

“Though he was often frustrated by some compromises forced on the show by the network,” Hilburn affirmed. “Cash used the show to express his core values. He brought on musical guests he believed in—not just Bob Dylan, but also Merle Haggard, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings. He used the show as his pulpit, if you will, to once again lift people’s spirits.

“People didn’t just like John’s music; they believed in him. The timing was crucial. If he had gotten a TV show just two years earlier, it would have been a disaster. America would have seen a desperate drug addict. Instead, they saw a national icon.”

The weekly ABC-TV slot also featured Cash’s road band with Carl Perkins, who was a welcome addition to the musical cast. Perkins wrote “Daddy Sang Bass,” the Cash recording that spotlights the Statler Brothers and Carter Family on background vocals.

“Carl Perkins is not given enough credit,” Bob Johnston exclaimed. “But Cash got him on that TV show and Carl was part of ‘A Boy Named Sue.’”

In Julie Chadwick’s The Man Who Carried Cash: Saul Holiff, Johnny Cash and the Making of an American Icon, we learn the reasons why Cash cut “A Boy Named Sue” and are now celebrating the 52nd anniversary of Johnny Cash At San Quentin.

“The entire book is filled with so many remarkable scenes,” emailed Chadwick to me in 2019. “Many of which have never before been revealed, such as how Johnny came to record ‘A Boy Named Sue’ after bumping into Shel Silverstein in an airport with Saul, to the time he hit rock bottom in 1967 and penned a tearful handwritten ten-page letter to his manager confessing his fear that he had lost June forever because of his out-of-control addiction.

“I feel like overall, I have done the two men’s relationship justice and brought a relatively hidden story to light. Saul also was the one who fought tooth and nail to convince Columbia Records to go along with the idea of a live album recorded at San Quentin, as they thought the concept had already been done with his Folsom concert.”

In his review of The Johnny Cash Show in the June 12, 1969 issue of Great Speckled Bird, the counterculture underground newspaper in Atlanta, Georgia, Gene Guerrero reviewed the ABC-TV/Screen Gems initial broadcast.

“With the inauguration of the Johnny Cash Show, country music has finally made it to network television. One can only hope and pray that it will take a couple of seasons before these corrupting influences set in.

“Dylan sang a couple of songs off his new album including ‘Girl From the North Country’ which he sings with Cash. In a non-contrived way Dylan and Cash singing together remind you of two kids practicing for their first recital. In this time of super-slick entertainers, that’s very refreshing.”

In our 1975 Melody Maker interview, Cash cited Dylan.

“I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963,” mused Johnny. “I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with. I was in Las Vegas in ’63 and ’64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence.

“We finally met at Newport in 1964. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He’s unique and original.

“I keep lookin’ around as we pass the middle of the 70s and I don’t see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn’t diminished. I get inspiration from him.”

As a teenager, in the very late fifties, Dylan, birth name Robert Allen Zimmerman, hitchhiked from Hibbing, Minnesota, to Duluth to see Cash and the Tennessee Two (Marshall Grant bass and Luther Perkins guitar) play at the Duluth amphitheater.

In the 2009 book A Heartbeat And A Guitar Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears by author Antonino D’Ambrosio, Johnny Western disclosed to D’Ambrosio in an interview witnessing a Dylan and Cash exchange where Dylan admitted, “Man, I didn’t just dig you; I breathed you.”

In November 1961, Cash had stuck his head inside the Columbia Records studio when talent scout/A&R man John Hammond was producing Dylan’s debut long player, Bob Dylan.

“Dylan was also grateful that Cash would constantly endorse his talents to skeptical Columbia Records executives,” Antonino expressed to me in a 2009 interview, “after the initial weak sales of his first platter, some calling it ‘Hammond’s folly,’ a jab at Hammond who signed Dylan to the label.”

Drummer and friend Jim Keltner on November 19, 1979 invited Knack drummer Bruce Gary and I to the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to attend Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming tour. Jimmy arranged our tickets and backstage passes. I was reviewing the concert for Melody Maker, too.

I had a very brief chat with Dylan. We had met earlier at Gold Star studios when he was producing a session with Clydie King and I was on a few May ’79 dates as a percussionist with Keltner on the Phil Spector-produced Ramones’ album End of the Century.

Bob inquired about Phil. I told him I had recently done an interview with Spector for Melody Maker. Phil talked about R&B vocalists, also listing Dion, John, Paul, Elvis, Johnny Cash and Bobby Darin as great singers. Dylan then removed his sunglasses. He has blue eyes like Eva Marie Saint, Charles Bukowski, and Kris Kristofferson. Bob offered a firm handshake, and sternly said, “Johnny Cash is a friend of mine.”

“Bob has told me time and again how much he loved John’s music and his failure to compromise,” reinforced Hilburn. “The bond was so great between them, even though they didn’t spend a lot of time together. Their relationship was more one of mutual inspiration and respect than time spent in each other’s company.

“Johnny Cash wasn’t about simply entertainment. Like Bob Dylan, he belongs with the great American artists, whether they are from the worlds of art, film or music. He told about his life and times with a strong, personal vision.”

© 2021 Harvey Kubernik

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For late summer 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century). Harvey and Andrew Loog Oldham wrote the liner essays to The Essential Carole King.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years.

His 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown appears in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada. The lineup includes LeRoi Jones, Johnny Otis, Ellen Willis, Nat Hentoff, Jerry Wexler, Jim Delehant, Ralph J. Gleason, Greil Marcus, and Cameron Crowe.

During 2020 he served as a Consultant on the two-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Kubernik is currently working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter Del Shannon.

Harvey is also spotlighted for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Womack, Bill Withers, Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, Damon Albarn of Blur, the Gorillaz and Antonio Vargas are featured.

In 2020 Harvey Kubernik was an interview subject in the Chris Sibley & David Tourje-directed short documentary entitled John Van Hamersveld: Crazy World Ain’t It. Van Hamersveld designed the iconic Endless Summer visual image and album covers for the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, the Beach Boys, the Kaleidoscope, and Blondie.

During 2019 Harvey was filmed for director Matt O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The premiere broadcast was in September 2020. He was also interviewed by director/producer Neil Norman for his GNP Crescendo documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard. Debut broadcast on television will be in 2021.

This decade Harvey was filmed for the currently in-production documentary about former Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross produced and directed by Brad Ross and Jonathan Rosenberg. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Shel Talmy, Richard Sherman, Don Peake, Kim Fowley, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.