-

Featured News

Shel Talmy: August 11, 1937 – November 14, 2024

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Jack Kerouac: Poetry for the Beat Generation / Blues and Haikus

By Harvey Kubernik

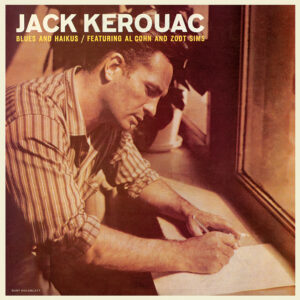

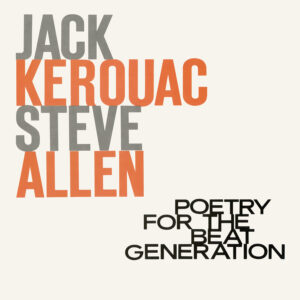

Jack Kerouac was a leading prose stylist of the beat movement in literature, author of On the Road, The Dharma Bums, and many other celebrated works. On December 9, 2022, Real Gone Music will release 100th birthday vinyl editions of the author’s first two spoken word albums. Poetry for the Beat Generation and Blues and Haikus.

Issued in 1959, Poetry for the Beat Generation was Kerouac’s recording debut. As the Real Gone Music press release explains, “Kerouac had completely bombed in his first set during a 1957 engagement at the Village Vanguard when TV personality, comedian, and musician Steve Allen volunteered to accompany him on piano during the second. The results were so impressive that legendary engineer Bob Thiele then brought the duo into the studio to record an album for Dot Records. In true, stream-of consciousness, beat fashion, the entire album was cut in one session with one take for each track, Allen’s piano weaving in and out and occasionally commenting on Kerouac’s verbal riffs to great effect.”

Dot President Randy Wood subsequently rejected the master due to its then-daring language and subject matter.

Only 100 now-very-valuable promo copies were made. Thiele then founded Hanover Records with Allen and released the record in 1959. The Real Gone title due in December will be pressed on milky clear vinyl.

Thiele also produced Kerouac’s second album, Blues and Haikus, issued on Hanover later the same year. But this time, he was accompanied by two jazz legends, saxmen Al Cohn and Zoot Sims.

“Big-time post-bop saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims made their bones in Woody Herman’s band, and here they provide effective counterpoint commentary to Kerouac’s readings,” explains the bio. “As for those who approach this release from a more literary angle, Blues and Haikus reflects Kerouac’s interest in Eastern religion and meditative practices as expressed in his novel The Dharma Bums as opposed to the more On the Road-like exultations of Poetry for the Beat Generation.

“But whatever your interest, boppish or bookish, Blues and Haikus is an essential document from one of our most iconic American authors, and, after listening to this album, one thing is for sure: no one is having a better time at this recording session than Kerouac himself! On the occasion of Kerouac’s 100th birthday year, this cult classic record comes in tobacco tan vinyl”

##

“When I had my record shop in the middle of Melbourne, Australia in the early 1970s next door to me was a book shop where an old Beat poet worked as the sales assistant,” recalled writer and musician, David N. Pepperell. “I found out he actually had copies of the two Jack Kerouac spoken word LP’s – impossibly rare and hard to get – and asked him to loan them to me for taping which he very kindly did.

“But this time I had read all of Jack’s books and they had vindicated my long held and much-dismissed idea that it was not necessary to try to fit into the world, that the world needed to fit into us. Jack’s wonderful novels extolled such a freedom and showed me that I was not alone in feeling an alien in this conservative world and that I had allies in my attempt to remain myself without having to compromise my beliefs to make my way forward. The marvelous writing of his books, the sensitivity to music and art and the love Jack had for all people moved me enormously and I decided if I did become a writer I would try and write like him or at least write words that he would approve of and agree with.

“Simply I became a Beat writer and have been so for the past 55 years. I dearly loved Jack’s writing but I was unprepared for the thrill of hearing his voice reading his work with such alacrity and conviction. This gave me a whole new view of him, his writing and his philosophy of life.

“These recordings – with fine musicians like Steve Allen and Zoot Sims and Al Cohn – are precious artefacts in the culture of literature and it is wonderful that they are again available to a New Generation seeking the same truths that Jack always told and always lived.

“Nice to have the records back on the format – plastic vinyl – that Jack originally recorded it on too!”

“Understanding Jack Kerouac and his writing begins with acknowledging his profound relationship with jazz,” explained historian Dennis McNally, author of Desolate Angel: Jack Kerouac, The Beat Generation & America.

“His best writing springs from the same improvisational — ‘composition on the fly’ — roots as jazz. The deep form that he sought was in the same realm as the sound that Charlie Parker explored. To boot, Kerouac had a beautiful reading voice. Paired with a fine pianist like Steve Allen, he delivered the goods.”

“Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and October in the Railroad Earth are rhapsodies,” offered actor/poet Harry E. Northup. “His prose is like the rolling hills & the open road America; you hear America in his singing, his search for a home. He wrote, that’s what he did. The men in the car in On the Road lived outside society as they crisscrossed America. They wrote, that’s what they lived for, not conformity.

“I read On the Road, when I was 16, in 1957, when it came out. I had begun hitchhiking when I was 11 and when I was 16, I hitchhiked from Sioux Ordnance Depot to Sidney, in western Nebraska many times. On the Road set my life ablaze with a yearning to burn, as Kerouac said, to blaze away. Did Kerouac blaze? He blazed! And gave us a taste of Romanticism.”

“Back in the late ’50s as I was completing my high school years, a too-hip classmate of mine tipped me to On the Road, enthused writer/author/reggae scholar, Roger Steffens.

“An avid reader, I devoured four or five books a week in my youth, but I had never encountered prose like Kerouac’s. Raised in Brooklyn, and North Jersey, I had no geographic knowledge outside of that cramped terrain, and when the opportunity arose, I bought a ’65 yellow Mustang and embarked on a speaking tour of the Midwest, reading Beat poetry to high school classes in a show called Poetry for People Who Hate Poetry. The Beats just felt good in my mouth, and it was thanks to Kerouac that I discovered them too.”

##

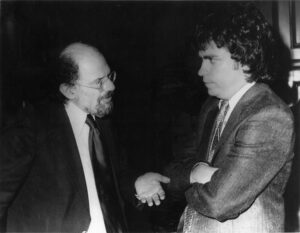

Harvey Kubernik and Ray Manzarek, 1992. (Photo: Heather Harris)

When I first met and interviewed Ray Manzarek co-founder of the Doors in 1974, he exclaimed, “If Jack Kerouac had never written On the Road the Doors would never have existed.”

Over the last five decades, Ray and I discussed Kerouac, the beat generation, and the impact on the Doors.

“My wife Dorothy and I went up to San Francisco in approximately 1963, during a spring break from UCLA. We tried to get up to San Francisco as much as possible. So, we went up to San Francisco and there was a poetry reading going on featuring Lew Welch, who had just come out of the forest after being a hermit for the last three or four years. He was just charged and wired out of his mind. Gary Snyder had just come back from Japan, wearing his Japanese schoolboy suit. He was mellow and tranquil. And Phillip Whalen read and was just a house of fire. Words were coming out of his mouth so fast you had to listen so closely.

“Somebody in the audience yelled, ‘speak slower!’ And Phillip Whalen stopped for a second after he heard that and said ‘listen faster! There were 2,000 people in the audience, man.”

We talked about the filmic influences on the Doors and their beatific recording, “L.A. Woman.”

“The Doors were part of Raymond Chandler, John Fante, Dalton Trumbo. It was the dark streets and The Day Of The Locust, ya know. Miss Lonelyhearts. That’s where the Doors come from. ‘L.A. Woman’ is just a fast L.A. kick ass freeway driving song in the key of A with barely any chord changes at all. And it just goes. It’s like Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg heading from Los Angeles up to Bakersfield on the 5 Freeway. Let’s go, man.”

In 2001, Manzarek reminisced about Jim Morrison and his poetry album An American Prayer.

“It was the first full-length rock ‘n roll poetry record. Back in the ‘50s, we used to get spoken word records by everybody, Dylan Thomas, E.E. Cummings, Kenneth Patchen. This is entirely different. I saw Jim’s words before he started writing songs. So, when you see his words on the page that’s poetry. I always thought of Jim as a good poet. But when he started writing songs, then everything became verse, chorus, verse and chorus. Really tight, and it was a whole other ball game. He put his words into an entirely different context. A musical context. A hit single in a three-minute context. I thought ‘Moonlight Drive’ was brilliant when I heard him sing it on the beach in Venice, I thought he had it.

“Lyrics are poetry. The words were well edited. Jim was good that way when it came to songs. When you are doing this written poetry, you can really stretch out and you can really expand.

“With his poetry, he’d throw this out, take this line, or two lines, but when it comes to music you gotta be very choosy because you only have a short period of time. Songs in a way, outside of like ‘The End,’ and ‘When the Music’s Over’ are sorta like haikus. The fit has to be very tight.”

In 1972 I coordinated two accredited upper division English and music curriculum courses conducted by Dr. James L. Wheeler, assistant professor in the School of Literature at San Diego State University. A story in the April 14, 1973 issue of Billboard magazine, the music trade hailed the department’s academic aim as “the world’s first university level rock studies program.”

I invited future authors publicist Sharon Lawrence and music journalist Danny Sugerman, along with singer/songwriter Carolyn Hester to speak to the class. I placed Jim Morrison’s The Lords & New Creatures on the required book list and suggested other titles, most notably, On the Road, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind, and Anthony Scaduto’s Dylan A Biography.

Around 1974 or 1975, I had two brief encounters in Hollywood with music journalist and writer, Lester Bangs, a student at SDSU during 1968-1970. It was Grelun Landon at RCA Records in Hollywood who introduced us. One was after a Mott the Hoople concert at the Hollywood Palladium. I praised Lester’s review of a Mott the Hoople LP for Creem. He was from El Cajon. We both frequented Ratner’s record shop in downtown San Diego and I already knew of his passion for Jack Kerouac. I mumbled something about appreciating his obituary on Kerouac in the November 29, 1969 Rolling Stone.

Lester immediately touted Kerouac’s On the Road and Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. In 1970, we both saw Ginsberg read his poetry at SDSU’s Aztec Bowl. Larry King was there, who later managed the Tower Records stores in San Diego and Hollywood.

##

Allen Ginsberg and Harvey Kubernik, 1982. (Photo: Suzan Carson / Courtesy Harvey Kubernik Archives)

In the mid-seventies I met Allen Ginsberg. I went with Leonard Cohen, after conducting an interview for Melody Maker, to see him read at Doug Weston’s Troubadour club in West Hollywood.

I interviewed Ginsberg at length three times in the eighties and nineties, and also co-promoted several of his Southern California readings in Los Angeles and Santa Monica. In 1982 I produced a live reading of Allen and Harold Norse at the Unitarian Church in Los Angeles.

In 1976 I provided handclaps on two tracks with deejay Rodney Bingenheimer on Cohen’s album Death of a Ladies’ Man, produced by Phil Spector at Gold Star Recording Studio. On one cut, Ginsberg and Bob Dylan join Cohen on “Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On.”

My first Ginsberg interview initially appeared in 1996 in HITS Magazine and a very short edited version was published in The Los Angeles Times Calendar section on April 7, 1997 when the daily newspaper asked me to pen one of the tribute stories on Ginsberg when he died.

When Allen passed on April 5, 1997 in New York City at his East Village loft of liver cancer and hepatitis at age 70, that evening Dylan was playing a concert in the Midlands at the Moncton Coliseum in Moncton, New Brunswick, and dedicated “Desolation Row” to Allen Ginsberg. Dylan had not been including the song in recent gigs.

During 1999, a portion of one of my Ginsberg interviews was published in The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats. In 2007 I wrote the liner notes to the first-ever CD release of Ginsberg’s Kaddish for Water Records.

“I learned a lot from William Carlos Williams, and the elders of my generation,” underlined Allen. “People who were much older than me when I was young. And that inter-generational amity is really important because it spreads myths from one generation to another of what you know, and all the techniques and the history.

“And I get the same thing whenever I get to work with younger people. And I learn from them. I don’t think I would have been singing if it wasn’t for younger Dylan. I mean he turned me on to actually singing. I remember the moment it was. It was a concert with Happy Traum that I went to and saw in Greenwich Village. I suddenly started to write my own lyrics, instead of Blake.

Allen Ginsberg, February 1967. (Photo: Roger Steffens)

“Dylan’s words were so beautiful. The first time I heard them I wept. I had come back from India, and Charlie Plymell, a poet I liked a lot in Bolinas, at a ‘Welcome Home Party’, played me. Dylan singing ‘Masters Of War’ from Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and I actually burst into tears. It was a sense that the torch had been passed to another generation. And somebody had the self-empowerment of saying, ‘I’ll Know My Song Well Before I Start Singing It.’

He spieled on the current interest in beat-inspired writers.

“The renewed interests stem from the fact that we were being more candid and truthful than most other public figures or writers at the time. We were switched over to writing a spoken idiomatic vernacular, actual American English, which turned on many generations later. Dylan said that Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues had inspired him to be a poet. That was his poetic inspiration.

“So, I think what happened is that we followed an older tradition, a lineage, of the modernists of the turn of the century continued their work into idiomatic talk and musical cadences and returned poetry back to its original sources and actual communication between people. That was picked up generation after generation up to people like U2, who are very much influenced by Burroughs in their presentation of visual material. Patti Smith, and Thurston Moore and Lee Renaldo of Sonic Youth are interested in poetry.

“Earlier, there was the poetry and music. King Pleasure, and the people who were putting together be-bop, syllable by syllable, like Lambert Ross and Hendrix. I knew them in 1948. We used to smoke pot together in the ’40s, when I knew Neal Cassidy, around Columbia when I was living on 92nd Street.

“Around 1944, ’45, Kerouac and I were listening to Symphony Sid, and I heard the whole repertoire of Thelonious Monk, ‘Round Midnight,’ ‘Ornithology’ and all that. I actually saw Charlie Parker, weekend after weekend a few years later at The Open Door. Later on, I spent an evening with him, now the Charlie Parker Place.

Allen Ginsberg, 1967. (Photo: Roger Steffens)

“Also in San Francisco, in the mid-’50s, there was a music and poetry scene. Mingus was involved with Kenneth Rexroth and Kenneth Pachen. And Fantasy records documented some of that. The Cellar in San Francisco.

“By the time I got around to getting on the radio, it was actually an AM station in Chicago with Studs Turkel; recorded the complete reading of Howl in Chicago, later used for the Fantasy record. It was broadcast censored. ’59. KPFA in the Bay Area then started broadcasting my stuff in San Francisco, a Pacifica station. Fantasy put out Howl and that got around. Then, Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, put out Kaddish. It was radio broadcast from Brandeis University.

“So, I think what happened is that we followed an older tradition, a lineage, of the modernists of the turn of the century continued their work into idiomatic talk and musical cadences and returned poetry back to its original sources and actual communication between people.

“I think you’ll find in Howl, sympathy. In fact, I remember when Kerouac was asked on the television show William F. Buckley Firing Line in the sixties what ‘Beat Generation’ meant, Kerouac said, ‘Sympathetic.’”

On Bob Dylan’s 1975-1976 semi-improvised Rolling Thunder Revue tour, Dylan performed a concert at the University of Lowell in Lowell, Massachusetts.

The following day, Dylan, Ginsberg and some band members visited Kerouac’s grave in Lowell on November 2, 1975. The trek was self-promoted, with revolving musicians making guest stops in clubs and small hall venues across the US. The road trip circus came to town, organized by Dylan’s friend Louie Kemp, with Bob Dylan assuming a role akin to Kerouac’s character Sal Paradise in On the Road.

I asked Ginsberg about Rolling Thunder and the film Renaldo & Clara culled from that expedition.

“Dylan delivers. Well, first of all, it’s Dylan extending himself to the extreme, and including all his friends and all his inspirers, and all his workable companions in a big circus going through America. A musical circus. His mother was along at one point. His kids were along at one point. His wife [Sara] was along. Joan Baez’s kid was along. So, it was this great family outing trying to hit all the small towns, originally, like in Kafka’s America. The traveling circus in Kafka’s America.

“For me it was great, and to hear Dylan so often, I was able to hear backstage, in the audience, from the side, in the wings, and go out to the furthest seats with a pass. He was at a peak of musicality and energy and inspiration. Like ‘One More Cup Of Coffee’ and ‘Idiot Wind,’ which is one of my favorite lyrics. A national lyric with its great ‘Circles around your skull . . .’ Really quite manic. It was great to see a band on a rock ‘n’ roll tour. Rolling Thunder Revue on a grand tour, and see all the work that went into it.

“Renaldo and Clara was a great artistic film that was mocked when it first came out, although it was a hit in Europe, or it was very much appreciated in Europe. Now, when people see it now, I think people will realize it was a great treasure. At first people were screaming ‘Four Hours!’ ‘What a big egotist.’ But actually it’s four hours of Dylan exploring the nature of identity of self, and pointing out there is no fixed identity. It was making a huge movie in an interesting way.”

Bob Dylan. Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, December 19, 1965. (Photo: Rodney Bingenheimer)

##

Dylan, via tour manager Bob Neuwirth, asked guitarist/arranger Mick Ronson to join the Rolling Thunder Revue. Ronson had been David Bowie’s lead guitarist in Bowie’s former band, the Spiders from Mars.

The current David Bowie documentary, Moonage Daydream, illustrates his debt and influence of Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs.

A song by Bowie, “All the Madmen,” first heard on The Man Who Sold the World, addresses Bowie’s half-brother Terry Burns and his struggles with mental illness. Bowie acknowledges Terry as the first explorer and seeker in the family.

During Bowie’s 1974 Diamond Dogs tour, I spent half an hour with David at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. We talked about beat generation literature and R&B music. We then attended an Al Green concert at the Universal Ampitheater.

I handed Bowie a paperback copy of Ann Charters’ Jack Kerouac: A Biography knowing his Spiders from Mars band name had a link to Kerouac’s On the Road: “exploding like spiders across the stars.” Charters’ book is seen by David’s hotel bedside in the Omnibus Cracked Actor 1975 UK documentary which aired on the BBC 1 channel.

Jack Kerouac also made an impression on teenage Janis Joplin, then living in Port Arthur, Texas. She attended Thomas Jefferson High School and later the University of Texas in Austin. Three of her favorite writers were Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure before she then fled to San Francisco.

“I grew up and got to see all the jazz cats in the clubs. Plus, I saw all the beatniks, and great writers and poets,” beamed Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane in a 2014 interview we did. “This is a world before 1967 and the Summer of Love. It started with the beatniks and poets.

“I think San Francisco was full of all these people who were talented and who were expressing themselves or their rights or playing music. And I think San Francisco has a lot to do with that. I don’t know if it’s the geomagnetic forces of the earth and the ocean but something went on there. It’s a lot different than the rest of the world.

“In 1965 I helped open the Matrix Club and did some booking in 1966 and ’67. People were coming in looking for places to play, the infamous Warlocks and Janis. I had an immediate influx of people.”

In a 1976 interview I conducted with Jerry Garcia inside Bill Graham’s Mill Valley residence for the now defunct Melody Maker, Jerry discussed the 1964-1976 sounds emanating from San Francisco. After the session was over, Jerry and I discussed Kerouac. I made a mental note, and had a feeling years later I’d reference Jerry and Jack’s contributions in my own nascent literary efforts.

In 1990, I was the Project Coordinator on The Jack Kerouac Collection for the Rhino/WordBeat label. I arranged for Ray Manzarek, Michael C Ford, Jerry Garcia and Michael McClure to contribute to the package booklet liner notes.

In the mid-eighties I produced spoken word and music programs with Manzarek and McClure on bookings with Charlie Haden, Paul Motian, Alan Broadbent, and the Minutemen at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica.

In our 1976 interview, Garcia said he first heard the word ‘beat generation’ in high school in San Francisco, and then a teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute told him about Kerouac’s On the Road.

In his Jack Kerouac Collection liner note contribution Garcia stated, “His way of perceiving music-the way he wrote about music and America – and the road, the romance of the American highway, it struck me. It stuck a primal chord. It felt familiar, something I wanted to join in. It wasn’t like a club, it was a way of seeing. It became so much a part of me that it’s hard to measure; I can’t separate who I am now from what I got from Kerouac. I don’t know if I would ever have had the courage or the vision to do something outside with my life – or even suspected the possibilities existed – if it weren’t for Kerouac opening those doors.”

In the product text, I wrote, “Jack Kerouac’s influence on my environment, then and now, is obvious. Kerouac’s written/verbal work helped me walk around the block so I can still cross the street seeking.”

“One of the things you could say about all the bands that came from San Francisco at that period of time was that none of them were very much alike,” stressed Garcia. “I think that the world has changed. I think the United States has changed very visibly in the last ten years. A lot of it had to do with what happened in San Francisco.

“I can’t say how or why, but I also think it’s affected everything. Just all the interest in things like ecology. All the interest in the sense of personal freedom as expressed by all kinds of movements. All these things were designed to free the human. Social overtones. All that stuff. The communal spirit. I really think the scene out here created the possibility for Woodstock to happen. The Monterey International Pop Festival. The thing, the activity, music and people. The set-up was out here.”

In Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song, he cites the Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’,” and lyricist Robert Hunter, the “in-house writer-poet, Robert Hunter, with a wide range of influences-everyone from Jack Kerouac to Rilke-and steeped in the songs of Stephen Foster.”

Kerouac’s fingerprints can also be found in dozens of recordings the last half century, including Tom Waits’ “Medley: Jack and Neal/California, Here I Come,” King Crimson’s “Neal and Jack and Me,” and 10,000 Maniac’s, “Hey Jack Kerouac.” Dylan’s “Desolation Row’ title is a nod to Kerouac’s Desolation Angels.

##

Ian Hunter and Harvey Kubernik, 1979. (Photo: Brad Elterman / Courtesy of the Harvey Kubernik Archives)

In 1978, I had a meal at Duke’s, the coffee shop at the Tropicana Hotel on Santa Monica Boulevard with record freak and sound hound, Guy Stevens. He was an avid R&B music collector, who did talent scout work at Island Records and produced albums by Mott the Hoople and the Clash.

Guy readily confessed that a Mott the Hoople track from Brain Capers, “The Wheel of the Quivering Meat Conception” was a direct homage to Kerouac’s own piece, “The Wheel of the Quivering Meat Conception.” He mentioned Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” and that he and Ian Hunter, bandleader of Mott the Hoople, were Dylan devoted fans. In fact, at the Mott the Hoople demo audition for Island records, where he was judging talent, Hunter sang a fragment of Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone,” later housed in the Mott The Hoople box set.

“It’s no secret that I’ve always acknowledged Bob Dylan as one of my heroes,” expressed Hunter in a 1998 interview we did. “Michael (Mick Ronson) always liked to go to Reno Sweeney’s (a club in New York). One night I said to Mick, ‘why don’t we go down to the Village?’

“I took him down to the Village. He’d never been there before. We went an all hell broke loose. Dylan was playing next door in a little café. Forty people in the room, and he performed what was to be the Desire album. It was great. There he was. What an electric night!

“Mick didn’t know what was going on. Bobby Neuwirth then got him the gig with the Rolling Thunder Revue. Dylan recognized me when Neuwirth told him who I was. We were introduced, and Dylan started jumping up and down saying ‘Mott The Hoople! Mott The Hoople!’ Here I was talking to Dylan, and I thought he didn’t like Mott The Hoople by the way he was acting. I didn’t need this shit mocking me. But then he turned round and said, ‘no. man, I dig Mott The Hoople! ‘Half Moon Bay.’ ‘Laugh At Me.’

“I can’t remember what I said to him that night…

“But the two artists I grew up with, Bob Dylan and the Stones (Mick Jagger) were both limited singers. But Jagger was the sexiest singer in the world, and Dylan would make your hair stand on the back of your head. Because his voice was so lousy. That’s the truth” he emphasized.

“I’ve got a lousy voice, and so have Randy Newman and Leonard Cohen. But it doesn’t really matter. I’m conscious of not being a good singer, but that’s just in your throat. I think we all get the message across.”

##

Patti Smith, has read and recorded a Kerouac poem “The Last Hotel” accompanied by music from Thurston Moore and Lenny Kaye. One of her favorite books is Kerouac’s Big Sur. Smith appeared in the Rolling Thunder Revue.

Smith, in a 2019 interview with Steven Gaydos of Variety, commented about the Beat poetry world.

“These people I got to know as my friends and mentors — William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso. They treated me really well when I was a girl working in a bookstore, writing poetry, and they became good friends as I got older and they were kind to my children. I never felt excluded. And in terms of rock and roll, I never genderized it — I just loved it, I was equally into Darlene Love and Jimi Hendrix.

“The Beats were all quite educated,” she said. “They all had gone through the Romantic poets and European literature and Rimbaud, and they had all this information — and the influence of jazz, with Kerouac writing while listening to jazz. They were all so evolved and intelligent their work was not just revolutionary — it had substance that we’re still plowing through. All these great teachers were his spiritual icons and they are all seeded in his work. And they all fought a lot of fights for us, censorship battles and [things like that]. They weren’t just workers and revolutionaries; they were teachers, and because many of them lived for a long time, we were privy to their teaching.”

In 2011, I interviewed Patti and asked about her improvisational skills and techniques in performing which I felt were akin to Kerouac’s recording endeavors.

“They are different responsibilities. Doing a record, one is doing something that hopefully will endure. And one is doing it in a very intimate situation. Just with one’s band members and a few technicians, and so it is very intimate, but one is mentally projecting toward the future and the people who’ll listen to it. Playing live you are right there with the people. I don’t think of live performance as enduring. It’s for the moment, somebody might bootleg it or tape it for themselves, but basically, I think of performance for the moment and it’s often more raucous, flawed, and you know, totally done for the people that are there.”

Twenty years ago, I interviewed Marianne Faithfull. In the early ’90s she was made a professor by Allen Ginsberg at the Naropa Poetry Institute in Colorado, where she taught lyric writing. Her certificate says: “Marianne Faithfull, Professor Of Poetics, Jack Kerouac School Of Disembodied Poets.”

That afternoon at the Chateau Marmont on Sunset Boulevard, she hailed the books of Kerouac, Burroughs and Ginsberg and grouped Dylan in her literary lineup. Marianne is glimpsed in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1965 UK tour portrait of Dylan, Dont Look Back.

“I find them very sexy all those guys. Wonderful. I adore Allen. The first time I went to Naropa, Allen was literally by my side like he is. There was a lot of criticism and ‘Who is the woman?’ ‘Why do you (Allen) think she can do this?’ And he didn’t say anything. ‘I just do.’ And then I came back again. We are very good friends. He also represents a lot of things for me that aren’t part of our friendship or our relationship. He is the greatest living American poet.

“I had never seen a rock person like Dylan or an American like him in 1965. Never. Never seen. Never in my wildest dreams could have imagined anyone like Bob in 1965. His brain, but I was frightened. I didn’t know they were probably more scared of me. He played me the album Bringing It All Back Home himself on his own. It was just amazing. And I worshipped him anyway. That was where I got very close to Allen, ‘cause Allen was the only sort of person I could recognize as being somewhat like me.”

##

On December 9th comes the return of Jack Kerouac on vinyl with Poetry for the Beat Generation and Blues and Haikus.

“Kerouac is the ultimate WAM, a white American male from the 20th century, 75 years down the road from his creative peak,” posed filmmaker Michael Hacker. “It’s impossible to read Kerouac now in any kind of quiet, in the stillness that reading demands, too much noise about Elon and Ye and so many other important things and nothing that sounds even remotely like silence anymore. I’d no more suggest to a person today who’s never read Kerouac to read him now than I’d suggest trying to find a decent hamburger in Los Angeles. What would be the point?

“But I would suggest listening to Kerouac, because in that space (with earbuds, natch) you can drown out the rest of the world and hear what he was trying to say and listen to his broken heart and see with him through his poetry what he was looking at. And that’s worthwhile. If you want to feel what San Francisco was like once upon a time, listen to October In The Railroad Earth. And the Haikus are so wonderful and moving and funny, Ginsberg said Jack was the only American who knew how to write Haiku. My favorite: ‘Useless! Useless!

Heavy rain driving into the sea.’”

“For us rock ‘n’ roll kids who came of age in the ’70s and ’80s, Kerouac was the portal into literature because he felt like rock and roll,” observed author and novelist, Daniel Weizmann.

“His kamikaze crop duster prose, his refusal to play the structure game, his ability to capture tenderness in the middle of chaos, his willingness to be openly enthused, to be jazzed – all of it brought him just a little closer to a spieling boss jock than some arch grey belles lettres schmuck. And despite incredible flights into the ethereal, Kerouac was trustworthy – he kept it real. He was a portal for us, just like he was a portal for the whole culture that led to us.

“And maybe it’s no accident that his masterpiece is about driving westward because Kerouac is also, in some funny way, a California writer, an embracer of the blazing sunlight, a seeker of the untamed. Whether walking the streets of L.A. or S.F. or sleeping in the wild fields, he is never a tourist.

“We claimed him for our own – a California rock ‘n’ roll hero — which is amazing when you realize what he also was – a poor French-Canadian kid from Massachusetts who couldn’t even speak English before the age of six, a printer’s son, a halfback who blew out his leg freshman season, a dishonorable discharge from the US Navy. But he made the journey, he beat down the path, and he was ours.”

“Jack Kerouac, for me, belongs with J. D. Salinger, Thomas Wolfe, and E. E. Cummings in the category of writers one must read before turning 20,” instructs poet/deejay and retired English and Literature Professor at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Dr. James Cushing.

Dr. James Cushing, 2010. (Photo by Henry Diltz / Courtesy of Gary Strobl, the Diltz Library)

“I read Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums at 19 and was utterly captivated by the narrator’s devil-may-care way of living and seeing and feeling, his free-flowing writing style, and, most of all, his sense of the freedom to be found on the road. I reread it (along with On the Road and Mexico City Blues) in my 50s and found myself feeling little or no sympathy for this sexist, egocentric jerk of a narrator, for whom the great end goal of the mythic road trip was to be home to spend Christmas with his mother. Christmas with his mother! For fuck’s sake!

“Add to that his blotto, hate-spewing appearance on William Buckley’s Firing Line and his support of the Vietnam War, and you have a larger picture: Kerouac as a 1950s bad-boy who work passed its sell-by date long ago.” Beat literature as it pertains to Romanticism: It’s time to ditch Kerouac in favor of Bob Kauffman, Diane Di Prima, Joanne Kyger, Gary Snyder, and don’t forget Richard Farina…”

“For those of us who entertain a terminally whimsical view of the human condition,” summarizes musician and author, Kenneth Kubernik, “‘the road’ is a mighty seductive metaphor. Infinite in all directions, literally and metaphysically, it’s an irresistible portal through which countless storytellers have journeyed, some with courage, some with reckless abandon, some content to ride shotgun – taking the wheel being too much responsibility.

“Homer took the bait; what was The Odyssey if not a mythically misguided road trip. Quixote and Panza’s canter through Andalusia in search of the impossible – another noble, if muddle-headed pursuit.

“America is no stranger to the beguiling indignities of heading out on lonesome highways, pedal down, no direction home, cat nip for romantics who struggle with the real thing.

“We read, enraptured, ‘watching the long, long skies over New Jersey, and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast and all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it…’ It’s bred in our bones, Manifest Destiny, Turner’s frontier thesis, the privilege of putting distance between yourself and your history. Lewis and Clark; Huck and Jim; Crosby and Hope (why not); Hunter Thompson and an assortment of Schedule 1 drugs. Springsteen would still be out there lost in his own tormented arcadia if Landau didn’t tether him to service more quotidian pursuits.

“My touchstone is that imperishable moment in Animal House when our heroes survey the wreckage around them and then, with clarion resolve rally the troops for – all together – a ‘Road Trip!’ I nearly rushed the screen to heed their call to action.

“Kerouac is, of course, the north star around which so much of this gravitational yearning takes place. He wrote the user’s manual for a generation (and a little beyond) eager to transform its’ post-war triumphalism into a debauched celebration of self-discovery and self-deception. His prose often crackled with the pop of a Philly Joe Jones rim shot; Ginsburg called it ‘bop prosody.’ Jack was crazy mad for Charlie Parker and the rattle and hum of 52nd Street; I hear him as more closely attuned to the tragic beauty of Art Pepper, whose playing caught the orphaned sound of an artist at the edge.

“Decades removed from its deeply-rooted ’50s setting, much of the writing has lost its narcotic kick. Like many a compelling if self-absorbed saxophone solos, the words tumble forth like a run-on sentence, that initial rush tempered by overstaying its welcome. The Beat movement itself now appears distant and, frankly diminished, even though their books, their posturing, their insouciant middle-finger to ‘I Like Ike’ conformity, remains consoling, even valiant to those who still consider the life of the mind valuable.

“In today’s heedless rush to celebrate the dazzling surfaces of our digital age – delighting the eye, dead to the touch – the idea of the road has retreated to a desolate backwater, at best a virtual memory as the Sal’s and Dean’s of today grind away in the Metaverse, jazzed by the clickity sound of Python swallowing them whole.”

“Alas, he never rocked my boat…I tried,” admitted wordsmith, record producer and author, Andrew Loog Oldham, “but ended up putting him in the same bin as Francoise Sagan …”

© Harvey Kubernik 2022

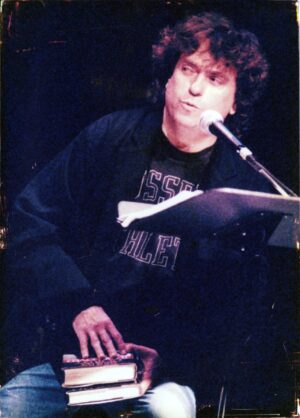

Harvey Kubernik. MET Theater reading, 1996. (Photo: Heather Harris)

Harvey Kubernik’s interview with Allen was published in Conversations With Allen Ginsberg, edited by David Stephen Calonne for the University Press of Mississippi in their 2019 Literary Conversations Series. Harvey is a contributor to Beat Scene magazine, and head of editorial for Record Collector News.

In 2020 The National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. exhibited a Harvey Kubernik essay on the landmark album The Band, which celebrated a 50th anniversary in 2019. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz.

Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972. For November 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

This century Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley’s The ’68 Comeback Special, the Ramones’ End of the Century, and Live at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, Big Brother & the Holding Company. Kubernik is the Project Coordinator of The Jack Kerouac Collection, a box set of recordings.

In November 2006, Harvey was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by the Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California. During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the two-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood.