-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Eddie Cochran and Gold Star Recording Studio

By Harvey Kubernik

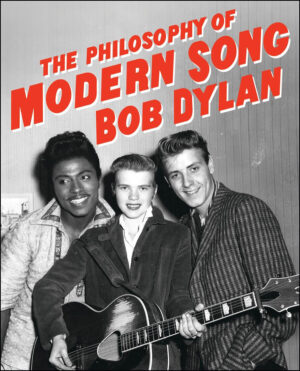

A 1957 photo of American singers Little Richard, Alis Lesley and Eddie Cochran in Australia grace the cover of Bob Dylan’s next book The Philosophy of Modern Song, which will be published by Simon & Schuster in November 2022. Both Bob Dylan and Eddie Cochran recorded at the landmark Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood, California.

Paul McCartney, as a 15 year-old, performed a version of Cochran’s record “Twenty Flight Rock” as the first song when he auditioned for John Lennon on July 6, 1957 in Liverpool.

Time to examine Gold Star’s audio legacy and Eddie Cochran.

There it sat, another anonymous cinder block facade in the working class section of Hollywood, far off the map of celebrity homes. But discerning eyes and ears knew that, behind this unprepossessing veneer, there lurked an authentic powerhouse of star-making capacity. This was Gold Star Studios, ground zero for transforming the fervid imaginings of pop music’s visionaries into three intoxicating minutes of backbeat and hum.

Like Merlin’s apprentices, Gold Star co-owners and engineers Stan Ross, Dave Gold, and Larry Levine presided over this exercise in alchemy, where inspiration and perspiration produced hit after hit. Their clients included Eddie Cochran, Ritchie Valens, Jack Nitzsche, Phil Spector, Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, Sonny & Cher, Cher as a solo artist, Buffalo Springfield, Charles Wright, Ike & Tina Turner, Stewart Levine, Hugh Masekela, Gloria Jones, the Righteous Brothers, Chan Romero, Brian Wilson with the Beach Boys, Iron Butterfly, the Cake, Harry Nilsson, Arthur Lee, Jimi Hendrix, Dr John, the Chipmunks, Chris Montez, HB Barnum, Buffalo Springfield, Dick Dale, Bobby Darin, Johnny Burnette, Dorsey Burnette, Bob Dylan, Clydie King, record producers Charlie Greene and Brian Stone, Thee Midnighters, Boris Karloff, Harold Batiste, Ronnie Spector, Darlene Love, Donna Loren, the Sunrays, Mark Guerrero, the Murmaids, Jackie DeShannon, the Runaways, the Ramones, the Go-Go’s, Concrete Blonde, the Watts 103rd Street Band, Shel Talmy, Led Zeppelin, Duane Eddy, Kim Fowley, Marlon Brando, the Band, the Seeds, the Monkees, the MFQ, and the Turtles.

Gold Star was also the primary studio where the instrumental music tracks and background vocals were pre-recorded for the monumental ABC-TV series Shindig! produced by visionary Jack Good.

“Gold Star felt and sounded different from any other Los Angeles studio,” explained Howard Kaylan, Turtles’ co-founder, to me in a 2013 dialogue. “You could literally smell the tubes inside the mixing board as they heated up. There was a richness to the sound that Western and United, our usual studios, never had. Those two rooms sounded clean, while Gold Star felt fat and funky. Perhaps we were all reading too much of the Spector legacy into the room, but I don’t think so. Our recordings from Gold Star always just sounded better to me. I miss that room.”

In the late seventies I supplied some percussion and handclaps on a handful of Spector-produced dates at Gold Star on sessions on Leonard Cohen, the Ramones and the Paley Brothers. In 1982 I produced my own session at Gold Star one afternoon. I was back in a candy store hearing playback results drenched with reverb and echo as the clock ran…

##

Stan Herbert Ross was born in Brooklyn in 1929. At age fifteen, he moved with his parents to Los Angeles, where his father worked as an electrician in Hollywood. He enrolled at Fairfax High in 1946 and began writing a music column in the Fairfax Colonial Gazette called “Musical Downbeat.”

As a teenager, Ross worked at Electro-Vox for four years and studied recording from a pioneer of modern disc recording, Bert B Gottschalk. Ross made one hit record there: “The Deck of Cards” by T Texas Tyler. Following this apprenticeship, Ross was ready to set up his own shop.

In a 2000 interview with me, portions were published in my 2014 book Turn Up The Radio! Pop, Rock and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972, Ross described the history and mystery of the Gold Star atmosphere. “Gold Star used to be a dentist’s office,” he said. “We started pulling teeth a different way.” Built in 1950, Gold Star endured at 6252 Santa Monica Boulevard until a fire destroyed the property in 1984. Upon closing that year, the property became a mini-mall.

“Gold Star was built for the songwriters,” Ross said. “They were fun, wonderful people to be around-Jimmy Van Heusen, Jimmy McHugh, Frank Loesser, Don Robertson, Sonny Burke.”

Johnny Crawford’s “Cindy’s Birthday,” Dobie Gray’s “The In Crowd,” and Chris Montez’s “Call Me” were Gold Star creations. Global music cult hero Scott Engel (later Scott Walker) first cut his teeth at Gold Star doing a variety of menial tasks while attending Los Angeles High School and playing bass with the favorite band on campus, the Routers. Phil Spector produced his 1958-1966 sessions inside Gold Star. Brian Wilson was a regular Gold Star visitor. In that room, he produced the Beach Boys’ “Do You Wanna Dance,” “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” the original version of “Heroes and Villains,” and “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times,” which featured the first usage of a theremin on a pop recording. A tiny portion of the first session of “Good Vibrations” was also tracked at the studio.

Stan Ross was behind the console for Jewel Aikens’ “The Birds and The Bees,” the first use of chorused guitar and was a favorite 45 rpm of Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, which provided the sound of a guitar plugged through a Leslie speaker, giving it an organ-like effect. Cream’s “Badge” and the Beatles’ “Let It Be” later fused the string-to-Leslie air-pumped speaker innovation. Kit Lambert mixed and mastered the Who’s “Call Me Lightning” and “I Can See For Miles” in the facility. Jody Reynolds’ “Endless Sleep,” one of Bob Dylan’s all-time records, and “Jungle Hop” by Don & Dewey were waxed at Gold Star.

“We used Studio A. Eddie Cochran used our Studio B, down the stairs by the parking lot,” recalled Stan Ross. “I cut ‘Tequila’ there, by the Champs. I did a whole lot of Eddie Cochran’s records, including “Summertime Blues,” “Twenty Flight Rock,” and “C’mon Everybody.” The vocal of Ritchie Valens’s “Donna” was recorded at Gold Star. The backing track was done up the street at Bob Keane’s studio. [He] owned Del-Fi Records.

“[The studio’s echo chamber] gave it the Wall of Sound feel. Dave [Gold] built the equipment and the echo chamber. We had so much fun with that echo chamber; it never sounded the same way twice.

“Gold Star brought a feeling, an emotional feeling. Gold Star was not a dead studio, but a live studio. The room was thirty by forty feet. It was all tube microphones. We kept tubes on longer than anyone else, because we understood that when a kick drum kicks into a tube, it’s not going to distort. A tube can expand. The microphones with tubes were better than the ones without the tubes, because if you don’t have a tube and you hit it heavy, suddenly it breaks up. But when you have a tube, it’s warm and emotional. It gets bigger and it expands. It allows for impulse. We didn’t use pop filters and wind screens-we got mouth noises. Isn’t that life?”

No story on Gold Star would be complete without citing resident recording engineer Larry Levine. Levine joined Gold Star in 1952 and engineered albums for Eddie Cochran, the Beach Boys, Sonny & Cher, and Dr John. Levine won a Grammy in 1965 for his work on “A Taste of Honey” by Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass. He reunited with Spector in the late ‘70s working on albums by Leonard Cohen and the Ramones. Levine engineered the Ramones’ End Of The Century with Boris Menart and assisted by Bruce Gold.

“I used to have a theory, and I don’t know if it’s right or wrong, but part of the reason we took so long in actually recording the songs was that Phil needed to tire out the musicians, or they got to the point where they were tired enough so they weren’t playing as individuals,” Larry underlined in a 2002 interview we collaborated on that appears in the liner notes I wrote for the 2002 expanded CD edition of End of the Century.

“But they would meld into the sound more that Phil had in his head. Good musicians start out and play as individuals and strive to play what Phil wants. As far as the room sound and the drum sound went, because the rooms were small, with low ceilings, the drum sound, unlike other studios with isolation, your drums sounded the way you wanted them to sound. They would change accordingly to whatever leakage was involved. As a matter of fact,” Levine continued, “Phil once said to me the bane of his recording existence was the drum sound. A lot of people attribute to echo to what Phil was doing. The echo enhanced the melding of ‘the wall of sound,’ but it didn’t create it. Within the room itself, all of this was happening and the echo was glue that kept it together.”

Herb Alpert later recruited Levine as chief engineer to design A&M Records’ Studio B, modeled after Dave Gold’s “compact” studio blueprints, developed and first installed at Gold Star.

Ahmet Ertegun and Phil Spector, ca. 1998. (Photo by Jim Roup)

Dolores “LaLa” Brooks was the immortal singer of the Crystals and the lead vocalist on a slew of their hits with the team of Spector, Gold, Ross, Levine and arranger, Jack Nitzsche. “Da Doo Ron Ron” and “Then He Kissed Me.” She is also featured on “Little Boy.” Brooks was born in Brooklyn in 1947. In 1962, the sixteen-year-old singer was invited to join the Crystals during a recording date for “Uptown,” which became a Top 15 chart hit that year. Los Angeles-based Darlene Love, also a member of the Blossoms, was then introduced to Spector by arranger Jack Nitzsche, who subsequently handled the lead vocal chores on the Crystals’ Gene Pitney-penned “He’s a Rebel.” The Crystals’ next single was “He’s Sure the Boy I Love,” spotlighting Love and the Blossoms. Phil then flew LaLa Brooks to Los Angeles for the lead vocal slot on the pulsating “Da Doo Ron Ron,” followed by the seismic “Then He Kissed Me” and the poptastic “Little Boy.”

When I did ‘Da Doo Ron Ron’ over and over, Phil was sort of like a perfectionist with that one,” reminisced Brooks in a 2014 telephone exchange. “I remember being pooped in the studio [laughs]. I wanted to run out that door so fast, but he kept going over and over. Thirty, forty takes. I would say, ‘When are you gonna get it?’ you know? I would initially sing with one headphone on. It was loud music, and I could not sing and keep both headphones on because it would blow my ears out [laughs]. Jokes apart, but a pair of good headphones can seriously help you avoid all the noise running around you. Anyway, I was singing about some monumental things. ‘Then He Kissed Me’ sounded so beautiful as it was being played before I put the track down. I knew it was different. I knew it was a hit. I could feel it. I could hear the changes. I knew it was the type of song that could go all the way around. Pop, into movies, and all that. I knew as a child how important the session guys were. I never took that for granted. In fact, I used to sit and watch them play. The strings, the movement, I really enjoyed. The kettledrums-they had a flow that was so captivating. So I never short-changed them for one moment. I knew they were definitely important. I think Jack Nitzsche’s roles were very much disrespected and not recognized [as] fully as they should have been. Even the artists on Phil’s records were not recognized [as] fully as Phil Spector, which is totally crazy to me. For someone to focus on a producer that much-what he is doing, how does he live, all of this-the intimate part of his life, it’s all nonsense and belittles the artist. That’s what happened to Jack Nitzsche. I remember what Jack said to me before he died: ‘LaLa. If it wasn’t for me, there’d be no Phil.'”

Before the turn of the century I did a lunch interview in Venice, California with Stan Ridgway, musician/songwriter and solo artist, the former vocalist with Wall Of Voodoo. During our nosh, Stan cited Phil Spector’s “Wall Of Sound” as the reason he named his former band Wall Of Voodoo. “I tried to go to Gold Star recording studio in the early ’70s, when I first moved to Hollywood from Pasadena. My goal was to be a janitor and empty trash at Gold Star. OK, I walk in. This is like in 1973, maybe 1972. Nobody was there except the engineer and co-owner, Stan Ross. And he was sitting there in the engineering booth. ‘Look, Mr Ross, my name is Stan and I’d like to work here. I love the stuff that has come out of this room.’ Obviously, everything had already happened. There had been tumultuous activity, but that was long ago. So I sat with Stan, and he said there was no work available. Then I said, ‘Is that the board that did all the stuff?’ ‘Yeah.’ And he was very nice to me and gave me a tour for a half hour. I got to touch the faders and see what was done. Then I went into the small room.

“That’s where Wall of Voodoo came from. I tore Phil’s records apart, and I tore Brian Wilson’s records apart. Wall of Voodoo started way back when I was trying to form a soundtrack company on Hollywood Boulevard across from The Masque before it happened. And I used to call it Acme Soundtracks. When the rhythm machines came in, I used to collect them and make recordings where I would ‘Wall-of-Sound’ these rhythm machines at the same tempo to build this sound. I said, this is like a ‘Wall of Sound.’ Then someone came in and said, ‘No, it’s a tropical voodoo thing.’ And I said, ‘It’s like a ‘Wall of Voodoo.’ We laughed and joked. We never thought that would be a name for a band. I know later in the ’70s, Phil Spector produced Dion at Gold Star. And I loved Dion. Another guy and voice who I really communicated with his whole swagger.

“And later, when I further investigated Phil’s records, I discovered who the ‘Wall of Sound’ players were. It coincided and dovetailed with my examination and involvement in jazz. ‘Hey man, that’s Barney Kessel playing guitar in there.’ And the West Coast jazz cats doing stuff with Phil-and they had jazz records-were gigging and recording with Shelly Manne. So everything made a lot of sense.”

Stan Ross, Sonny Bono and Chip Douglas at Gold Star, ca. 1973. (Photo by Henry Diltz, courtesy of Gary Strobl)

Before he managed Van Halen for the first five years of their career, music business veteran and agent Marshall Berle, who signed the Beach Boys to the William Morris Agency in 1962, attended Fairfax High School with fellow classmate Phil Spector and encountered Eddie Cochran at Gold Star one afternoon in 1960. “I met Eddie at Gold Star just before he died,” marveled Berle in a 2014 conversation we had. “In those days, instead of using a drum, he sometimes utilized a cardboard box or suitcase. He’s in The Girl Can’t Help It movie.”

“There’s no soundtrack album to it,” emphasized record producer and author Andrew Loog Oldham in our 2006 interview. “The Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran sequences aren’t just slotted-in videos. I saw it before I saw Eddie play live. I saw them on-screen, and later in the UK at a personal appearance. Both galvanized me. Dark-haired guys didn’t interest me, only blondes, because I could be it.

“I heard the Gold Star recording of ‘To Know Him Is to Love Him’ that Phil [Spector] and Stan Ross did with the Teddy Bears in the UK. It made an impact because of the use of the room. The usage of tape delay. You knew something was going on, even if you didn’t know what it was. Later, I recorded the Rolling Stones’ ‘Not Fade Away’-or let’s say ‘Little Red Rooster.’ You realized, by recording in similar mono circumstances, in London’s Regent Sounds as opposed to Gold Star, or wherever Phil did ‘To Know Him is To Love Him,’ what the room brought to the game. Maybe one of the things that drew me to the record was that there was a subliminal audio text from Eddie Cochran records, Eddie had already recorded ‘Summertime Blues’ at Gold Star.”

During 2014 I interviewed record producer, songwriter and former deejay on the Little Steven Underground Garage SiriusXM channel Kim Fowley about Eddie Cochran and Gold Star.

“I went to Gold Star my first day in Hollywood, on February 3, 1959. It was the day Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper died in an airplane crash in Iowa. I took it upon myself to take their place. I thought that they had passed the baton on to me from beyond. I thought it was my turn to take over.

“I met the legendary rockabilly cats Johnny and Dorsey Burnette in 1959. It was during that day in Hollywood at Gold Star, around a Champs recording session I was covering for Dig magazine. I was their campus correspondent and [was] invited to have lunch with Dorsey and Johnny, who were in to play on a long-forgotten B-side of a Champs single. Dave Burgess was the producer, who later produced Jerry Fuller. The Burnette Trio were a band. In those days, pre-Beatles, you didn’t sing and play at the same time and write. There was a songwriter, the musicians, and there were the singers. Three different components who performed on the record.

“So, Gold Star got me going. A year later, I was number one in the world. I produced ‘Nut Rocker’ in 1960 under the name B Bumble & the Stingers on Transworld Records. I wasn’t allowed to be in the room at the session, so I took a walk. René Hall was on guitar and bass, Al Hazan on piano, and Jesse Sailes was the drummer. I was just the publisher and the writer. I was 22 years old. I had a partnership with Gary Paxton. He was a hillbilly genius who worked with a Hollywood child. One hustler and conceptualist. One musical and vocal guy. We did well, did work together, and we quit. We were both damaged goods, but interesting people in terms of what our product was.

“I then met Eddie Cochran and songwriters Sharon Sheeley, Jackie DeShannon and Eddie’s record producer and co-writer, Jerry Capehart.

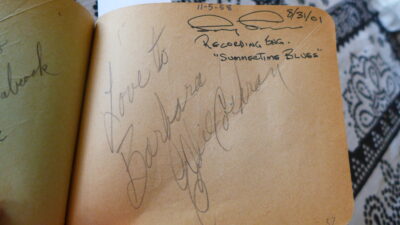

Eddie Cochran autograph.

(Roger Steffens Archives)

“I scored in 1960 with the Hollywood Argyles’ ‘Alley-Oop’ on Lute Records. [They] were the white Coasters, with a black backing group that no one ever saw. Gary Paxton did the lead vocal, Sandy Nelson did the caveman yell, and a girl who was tall with red hair, who was dating Gary, was the high voice on the record. I was co-publisher and co-producer. Bill Parr was the engineer. “We did ‘Alley-Oop’ at American Recording Studio. The session recording had keyboardist Gaynel Hodge, a member of the Hollywood Flames who sang with the Platters and co-wrote ‘Earth Angel’ for the Penguins, as well as Harper Cosby, who was on Johnny Otis’s ‘Willie and the Hand Jive,’ [and] drummers Sandy Nelson and Ronnie Selico, who worked with the Olympics and is heard on ‘Big Boy Pete.’ Ronnie was also on the Marathons’ ‘Peanut Butter.’ He later went with Ray Charles and Shuggie Otis, and is on Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats album.

“I learned that you had to have black people with white people on my sessions to get the groove. We then marched into Gold Star, [which] had mastering facilities, and Stan Ross mastered the record. Stan proclaimed it was going to be a number-one record. He was right.

“As a visitor to Gold Star, it was the epicenter of teenage rock ‘n’ roll recording culture in 1959. If you were in Memphis, Tennessee, you would knock on the door of Sun Records. If you were in Detroit, Michigan, you would knock on the door at Motown. But in 1959, I went to Gold Star. ‘Here I am. Let’s see if I get accepted.’ If you got accepted, you were off and running. You start at the top, and I did. So, I will always be grateful.

“If a kid had a hundred dollars, he could cut a hit record at Gold Star if he saved it or got his friends and family to pitch in with band members. I later worked with their engineer, Doc Siegel, as well. You could go in there and not get intimidated, and you had equal footing with the legendary guys. I saw Eddie Cochran work at Gold Star. He invited me in to watch, listen, and learn,” Kim revealed.

“I also attended Eddie’s session for ‘Sittin’ in the Balcony’ that came out on Liberty. In 1960 I was throwing shows on Sunset Boulevard for teenagers at Jimmy Maddin’s venue, The Summit-later The Red Velvet. At night deejays Frosty Harris and Jimmy O’Neill, who were on KRLA, would come down. I was the last guy to book Eddie Cochran in America before he died. He came out and did ‘Three Steps to Heaven.’ He died three weeks later in England.

“Go ask Paul McCartney, Keith Richards and Pete Townshend about Eddie Cochran,” instructed Fowley.

“I already have,” I responded.

“Their bands have done Eddie’s tunes on stage,” Kim underscored. “His catalogue has been covered by the Rolling Stones, the Move, Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band, Led Zeppelin, Blue Cheer, Sex Pistols, the Stray Cats and Lemmy Kilmister. The Who cut ‘Summertime Blues.'”

“Eddie Cochran. A great one for sure,” volunteered Slim Jim Phantom of the Stray Cats in a 2022 email. “We always say Eddie is the greatest rock star ever!”

Harvey Kubernik and Jackie DeShannon, 2010. (Photo by Justin Pierce)

2022 Harvey Kubernik

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows published in 2014 and Neil Young Heart of Gold during 2015. Kubernik also authored 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For November 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others. Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century). Kubernik is very active in the music documentary world. During 2020 Harvey served as a Consultant on the two-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood.