-

Featured News

Shel Talmy: August 11, 1937 – November 14, 2024

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G

By Harvey Kubernik

The legendary and influential record producer Shel Talmy passed away in mid-November from a stroke at age 87.

Talmy arranged and produced the Kinks recordings 1964-1967, “My G -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

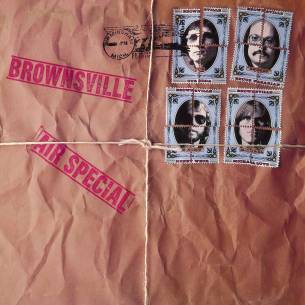

Brownsville – Air Special

By Doug Sheppard

BROWNSVILLE – Air Special (Rock Candy) CD

Brownsville Station hit the big leagues with the success of “Smokin’ in the Boy’s Room” (#3) and “Kings of the Party” (#31) in 1974, but by 1976, they were in a lull. With their recent Motor City Connection album failing to chart and a parting of ways with their label, Big Tree, the trio format (adopted after their second album) had seemingly run its course. They needed a lift and got in the form of a new label (Private Stock) and especially the addition of second guitarist Bruce Nazarian, a monster player who’d been on countless Detroit soul records.

Nazarian proved to be the perfect complement for fellow axe men Cub Koda and Michael Lutz (with whom Nazarian alternated on bass), invigorating the resulting Brownsville Station album with tons of slide guitar wizardry, blues boogie riffs befitting Koda’s formidable record collection and the loose vibe inherent on all Brownsville recordings. Famed producer Eddie Kramer knew how to get it all on tape, and the track lineup was their best yet, featuring a killer remake of “Lady (Put the Light on Me)” (a glam rock obscurity by Big John’s Rock ’n’ Roll Circus) and especially “Martian Boogie.”

Recorded live in one take, “Martian Boogie” was B-movie sci-fi, urban blues and riff rock fused into one rocket that the band was sure would take them back to the moon—if not the home planet of the song’s protagonist. Indeed, it spent seven weeks on the national chart and grabbed the top spot in a number of markets. But just as that rocket entered the top 60 at #59, it smashed headlong into an asteroid, exploded into 1,000 pieces, fell off the charts and left its creators stunned. Not long after, Private Stock folded. As Koda recalled in the liners to Rhino’s 1993 Brownsville compilation, “it took all the fight out of the band, just like air escaping from a punctured tire.”

Morale may have been down, but the chemistry was intact when they recorded their next album for Epic Records, 1978’s Air Special. Another hotshot producer, Tom Werman (of Cheap Trick and Ted Nugent fame, among others) was at the helm—giving the resulting album a big arena rock feel, with the drums of Henry “H-Bomb” Weck in particular booming in the mix (thankfully not ’80s-style). Much to their chagrin, the band were also forced to record Hello’s recent hit, “Love Stealer” (ironically, penned by Phil Wainman, also the coauthor of “Lady” from the previous album) as a gambit to get on AOR radio.

It failed, as did Air Special, but it wasn’t for lack of quality. “Taste of Your Love,” “Tears of a Fool” and “Never Say Die” are biting hard rockers—the latter taking on an ironic, almost eerie quality thanks to the state of the band, not to mention subtle synths. And befitting a band with so much contempt for the disco and AOR dominating the charts, Brownsville covers “Who Do You Love” Diddley-style, “Down the Road Apiece” and even a Benny Goodman instrumental, “Airmail Special”—rocked up like a ’70s Johnny & the Hurricanes. The swamp blues of “Cooda Crawlin’” follows the same thread, and if Air Special doesn’t quite have another “Martian Boogie” like its predecessor, it’s a solid, commendable effort. Predictably, however, it wasn’t what the record-buying public wanted to hear, and a 1979 breakup was inevitable. (Doug Sheppard)

Cub Koda Interview

The late Cub Koda loved to talk about the blues and vintage rock’n’ roll records close to his heart, but was a little more guarded when discussing his old band. An interview I conducted with Cub on January 16, 1994, mostly reflected this, as questions about Brownsville were often met by quick, boilerplate answers. But occasionally, Cub’s pride in his past life would seep through, such as when the conversation turned to the band’s final two albums. The following are excerpts from that interview, which provide an addendum to the excellent liners to this reissue, which feature interviews with manager Al Nalli and producer Tom Werman.

When did you get on Private Stock, and when did Bruce Nazarian join?

Both around late ’76.

You said that Brownsville was influenced by science fiction movies. Were there any in particular that influenced “Martian Boogie”?

It was real amalgam of different sounds. It was everything from those old flying saucer records from the ’50s, “Martian Hop” by the Ran-Dells, Not of This Earth, Plan 9 from Outer Space, Edward D Wood.

How did you do some of those sound effects, like the saucer taking off at the beginning—or the sound effect after you say, “The guy sittin’ next to me was a Martian”? Was that canned studio sound effects?

Oh no, that was all generated right there on the spot. Most of the flying saucer noises were using an old Echoplex tape-delay unit, and just manipulating that wire from real slow to real fast would regenerate at a certain point and create that sort of whooshing, swooping sound.

So there’s no overdubs on that song?

No, not really. There’s obviously the usual amount of mixing involved, but pretty much everything that was created on that was done in all one take.

How did you do the vocal effects for when the Martian says, “Why no, they’re Martian cigarettes—here, try one”?

The old pinch your nose with your fingers.

It sounds almost like it’s going through something.

Well, yeah, when we mixed it down, we put in a little extra gurgle on it—but the basic tonality of [in a high-pitched voice] “Why no, they’re Martian cigarettes—here, try one” was there.

Oh, so that’s you?

Yeah.

Why was the band so disappointed when it didn’t do well?

Because we knew it was great. We knew it was as solid as “Smokin’”—if not solider. And basically, the record company booted it. Midway through the record’s chart run, and just when it gets up to that Top 50-Top 40 crucial spot to push it up all the rest of the way, Larry Uttal fired the entire promotional staff and brought in all new guys who had no knowledge of where the record was currently sitting at various radio stations. I mean, that record was like number 1 in 20 markets. The record company basically pissed away a hit.

How did the contract with Epic come about?

Well, we split from Private Stock, and Epic wanted to sign us, so we did. And they assigned Tom Werman to produce us.

He’s known for producing Ted Nugent and Cheap Trick, so how did that mesh with you guys? He’s known for being a heavy metal producer.

Yeah, he’s pretty much got his own agenda.

Why was the name changed to “Brownsville” for that album?

That was the record company’s idea—thinking that it was more hip. There are 11 letters in Brownsville, and they just felt like, “Hey, let’s start with a fresh image. Let’s cut the band’s name down to just Brownsville. It’ll be easier to fill out forms, it’ll be easier for the J-cards in the record bins and all that.”

How did that idea sit with you?

I thought it was pretty fuckin’ stupid.

Did you have any say, or maybe argue with them about it?

Yeah, but you just signed with the record company; you’re willing to go along with whatever, so you’ll put up with a few asinine ideas. I mean, hey, if that album had become a big hit, then they would have cranked out and said, “Oh yeah, great idea. See? That’s the reason why it was a hit: Because we changed our name.”

What’s your take on Air Special?

Oh, it’s got some really great moments on it. I love “Down the Road Apiece,” I love “Cooda Crawlin’” and “Tears of a Fool” and the version of “Who Do You Love”—that came out before Thorogood’s. There was a lot of really good stuff in there; it’s just the state of mind of the band at that time wasn’t good. We were just barely hanging together by a thread. And it was sort of like while we were cutting the album, almost everybody was going: “Well, if this album doesn’t make it, then we’re breaking up!” And I don’t think you can create really great stuff—certainly not joy-filled music—under those circumstances.

You didn’t think “Love Stealer” was any good, correct?

Nobody did. It was forced on us by the record company, and then the thing summarily stiffed. I hated that song so much; I mean, that’s the only Brownsville Station record I never played on.

What do you mean you didn’t play on it?

I don’t play on the band track. And originally, Michael Lutz sang lead on it, and the record company didn’t like his vocals, so they flew me out to LA and had me overdub the vocal.

So when was Brownsville’s last gig?

About June or July of ’79.

What was the breakup about?

I’d rather not comment on that at all.

Did you feel vindicated by punk rock, particularly that the Detroit ethos of bands like the Stooges, the MC5 and you guys was an inspiration for it?

I could definitely relate to it. I could see what they were doing—groups like the Sex Pistols, the Damned, etc. Yeah.

Do you like punk rock?

Some of it.

Do you have any opinion on current music, like grunge, rap or other recent developments?

[In] any genre of music, we seem to be currently in a climate of summer reruns; you know, where you look at bands that are just doing the exact same thing that we were doing or garage bands were doing back in the late ’60s—only not quite as well. Maybe rock ’n’ roll has shot itself in the foot and has just reached the point of diminishing returns—to where now all it’s gonna be is just bands copying other bands copying other bands, and just the same crap over and over again. Maybe rock ’n’ roll has played out its hand; I don’t know.

What do you think rock would need to get back where it was in the ’50s and ’60s?

I don’t know. In some ways, rock criticism has done more to hurt rock ’n’ roll than anything else. Even though I’m a “rock critic,” I really do believe that. I think it just became so analytical that the very things that made for what everyone now looks at as rock ’n’ roll’s classic moments never could have existed in that kind of a thing.

A Robert Christgau—whatever he wrote about us excepted (1)—reporting back in the ’50s and the ’60s with that same snooty fucking attitude … hey, he would have made sure that an Elvis Presley never happened. There would not have been a rockabilly movement. There would not have been a ’60s garage band movement. There never would have been “Gloria” by the Shadows of Knight, there never would have been “Louie Louie” by the Kingsmen, there never would have been “California Sun” by the Rivieras, there never would have been “Surfin’ Bird” by the Trashmen, there never would have been “Da Doo Ron Ron” or any of the Phil Spector records. None of that shit would have happened if rock criticism had existed back then.

Do you think maybe they’re taking rock ’n’ roll too seriously?

Fuck yeah! Fuck yeah. The music at its purest cellular level, and what always keeps reviving it … when grunge suddenly happened out of seemingly nowhere, hey, it was a reaction to the bloated pop. It was a chance that kids nowadays could have rock ’n’ roll bands that they could call their own, not some 50-year-old fucking dinosaurs who their parents used to listen to.

And that’s what it is. Because you also gotta understand, it is pop music—and it’s all based on who’s got the coolest haircut and the newest shoes. Somebody’s always gonna come along with a great haircut—and it doesn’t even matter if the stuff is quality or if it’s good. The only difference between then and now is rock ’n’ roll is no longer the music of choice of America’s young people. There was a time that rock ’n’ roll was the coolest music around, and if you were cool, that’s what you listened to. You couldn’t help it; if it was the ’50s, you listened to Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis—and in the ’60s, it was the girl group stuff and then the Beatles came along, and then it just went right through the whole history of the music.

But somewhere in the last 10 years, especially in the last five years, it is no longer thee first music of choice of America’s young people. They would rather worship at the shrine of a plastic disco goddess like Madonna or Michael Jackson or Janet Jackson or updated disco dance music. They would rather listen to rap.

I get the impression you didn’t like disco very much when it came around in the late ’70s.

I don’t know anybody who did—except maybe the Bee Gees, who made a couple mil.

Rule 21 of the Cub Koda Rules of Rock ’n’ Roll: What is popular seldom, if ever, corresponds to what is good. Something can be wildly popular and not have very much of a shelf life at all. There is termite trash that just keeps burrowing in forever and ever, and assumes a life of its own—and then there’s like elephant trash that just sort of stomps everything in its path. Irregardless of everything, you just sit there scratching your head and going: How can this become so popular? There’s nothing there to it; it’s pee pee caca—no substance.

Do you think maybe rock radio—like the classic rock format continually playing the same thing—has destroyed some of rock ’n’ roll also?

Yeah, it might. I think people get the radio they deserve; I think they get the television they deserve. And if they want to change it, it’s up to them to change it. Not just sit there and listen to Led Zeppelin do “Stairway to Fucking [sic] Heaven” for the 9,000th time that day, and sit there and piss and moan and go, “Well, jeez, do you think that’s killed off rock ’n’ roll?” Well, yeah! Of course it has.

But there’s a lot of other factors. The fact that rock ’n’ roll has always been a bastard industry; it always has been on the fringe of respectability within the music industry itself. But once it started selling so much, then it was like: “Hey, man, we’ll sign every longhaired group we can find. They like long hair, they like dark hair” … and then try to do their version of it.

And that’s how bubblegum music was created—first with the teen idols in the ’50s. They knew that there was only one Elvis Presley to go around, but if they got another guy with dark hair and tight pants and a red sweater, and they got him to sing about high school, and he was cute—hey, maybe he’d sell some records. It doesn’t matter if 30 years after the fact that nobody listens to Fabian. At one time he was as big as Elvis.

That’s why now you see the latest rap group on Arsenio — here today, gone tomorrow. It’s like a crop of asparagus: There’ll be another one to replace that rapper in another 10 weeks. And then that one will sell eight zillion copies of whatever. It’s a real parasitic, bottom-feeder kind of industry — and it always has been.

Have you ever read Hit Men by Fredric Dannen?

No.

It just tells the story about all the cutthroat bullshit in the music industry behind the scenes. I’m sure if you read it, it probably wouldn’t be anything new to you, since …

… I lived through it.

When I read it, I wasn’t shocked, but it was enlightening.

I’m aware of that book, and the only thing I can tell you is: There are stories that I know of true things that happened in the wild and wooly days of rock ’n’ roll—when rock ’n’ roll was king—that make the stories in that book [look] mild. Guys like Morris Levy.

Well, it talks about him all through that book.

They didn’t even get into any of the real good Morris stories, but then again, Morris was alive when that book came out.

What do you think of the current box set trend?

Oh, I think it’s pretty neat. Let the buyer beware; there’s some stuff that you look at and go: “Well, the only reason they got a box set is because they got four albums out.” But [with] a lot of artists, hey, it’s really good to have it all in one place. I like it.

I have no problem with modern technology as far as the marketplace goes. When I think of where record collecting or even delving into the music was 20 years ago, and where it is now—hey, it’s 100 percent better now. I’m all for compact discs.

Compact discs have brought back a lot of old albums.

Yeah, sure, because once they figured out how to sell us our record collection back to us again, they put everything out on CD.

A lot of the stuff would never have been reissued in the first place.

If it was still [vinyl] albums, I don’t think there would have been a Brownsville Station best of.

Bonus: Cub Finds Brownsville Station ‘Cover’

I was in a record store on the road and found this Joel Scott Hill bootleg with “Rock & Roll Holiday” [Brownsville’s first single, penned by Koda] on it and I thought: “Wow, I didn’t know there was a cover!” When I got it home and played it, it was actually us—on a Joel Scott Hill bootleg. [laughs]

Bonus: Cub on George Thorogood

I don’t know why he would think he could beat Bo Diddley at pool—let alone anything.

[1] For context, earlier in the conversation we had discussed Christgau’s terse pan of Brownsville Station: “They weren’t smokin’ in that boys’ room — just taking a quick dump.” Interestingly, the self-dubbed Dean of American Rock Critics later praised the last album Cub recorded before his death, Noise Monkeys (2000) — singling out “Fast Food-Slow Death” and “Look at That White Girl Dance” as noteworthy tracks.