-

Featured News

The Rolling Stones’ 2024 North American Tour…and so much more

By Harvey Kubernik

The Rolling Stones will embark on their North America! Stones Tour ‘24 Hackney Diamonds which kicks off on April 28, 2024 in Houston, Texas. The band will be performing in 16

By Harvey Kubernik

The Rolling Stones will embark on their North America! Stones Tour ‘24 Hackney Diamonds which kicks off on April 28, 2024 in Houston, Texas. The band will be performing in 16 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

The Sons of Adam: Saturday’s sons of the Sunset Strip

By Greg Prevost & Mike Stax

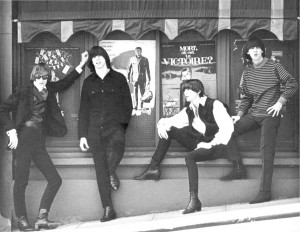

From late ’65 until early ’67, the Sons of Adam were one of the most happening bands on the Sunset Strip, playing to packed houses at clubs like Gazzarri’s, Bito Lido’s and the Whisky A Go Go. They had the right sound, the right image, and some of the most talented musicians on the scene. They even had their share of lucky breaks, including an appearance in a major Hollywood movie and a deal with Decca Records. Arthur Lee even gave them one of his songs. Yet somehow the Sons of Adam never managed to lift themselves out of the Hollywood club scene and into the major leagues. Today they’re mostly remembered as the band Michael Stuart was in before he joined Love, or the band Randy Holden was in before joining Blue Cheer. What’s too often overlooked is that the Sons have a proud legacy of their own: three enormously great 45 releases, and a story that is long overdue to be told.

INTRODUCTION by Greg Prevost

I first discovered the Sons of Adam when I heard “Take My Hand” in late 1966 on WSAY, one of the greatest radio stations on the planet. Unfortunately, trying to find the 45 at my favorite record stores back then was more challenging than nuclear physics. On the positive side, I got to be friends with one of the DJ’s there (Mike Melody) and he gave me the station’s ‘extra’ copy (they used to send out two to the stations back then, which is actually where I got my other Decca 45 as well).

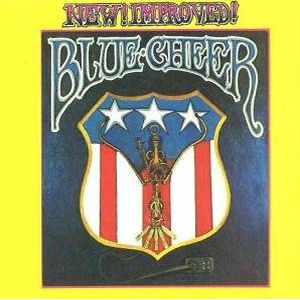

Anyway, a short time later, Blue Cheer’s Vincebus Eruptum came out and I became obsessed with them and anything that had to do with them (Randy Holden is on one side of their New! Improved! album, as you most likely know). Due to this obsession, in time I figured out that Randy was in this fantastic band (The Sons Of Adam) and all the pieces started falling into place.

It is obvious to most of you that I no longer publish Outasite magazine, and the Randy Holden piece that was in the last issue (#4) is now long gone. The interview with Randy was done mostly by phone over a period of time starting November 7, 1997 to November 17, 1997, and a few things via email in 1999. Since that time I have also been in touch with Jac Ttanna, a.ka. Joe Kooken, a founding member of the band as well, and he added, corrected and filled in a lot of the missing chapters (the interview with Jac was done by phone and email starting in September 2000 up to present time). Unfortunately, Outasite was defunct, but fortunately there is Ugly Things and my friend Mike Stax who suggested we do the DEFINITIVE Sons Of Adam story together, which is what we did and what this turned out to be. Mike got hold of Michael Stuart and Craig Tarwater, filled in the rest of the chapters, and reconstructed all this into what you are looking at. I’ll stop rambling and say one last thing before the story unfolds: The Sons of Adam ruled the world then, now, and in the next one.

CHAPTER 1: Iridescent in Baltimore

The Sons of Adam story begins in Baltimore, Maryland, in the early 1960s, when lead guitarist Randy Holden and bass player Mike Port first started playing in bands together. Holden was originally from Pennsylvania. ” I traveled all over the East Coast from the time I was able to walk,” he says. “I started getting into music when I was very young. I also decided that I needed to go somewhere besides where I was to really do it.”

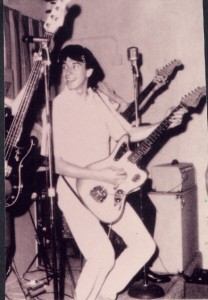

Randy had begun to play guitar at the age of seven. “My cousin and I found one in the attic of her mom and dad’s house out in the country. We stayed in the attic with it all night, fooling around with it, figuring out melodies. That was my introduction, or whatever you’d like to call it, to the guitar.”

Inspired by what he calls the “big bang twang” sound of Duane Eddy, Holden later got his first electric guitar, a Silvertone, later upgrading to a Fender Stratocaster. He remembers playing with two or three different bands in the Baltimore area, including the Irridescents. Getting his first instrument clearly led him on a path to music stardom, which quite a few people who play an instrument want, that is why they will look into areas such as ‘electric guitars for sale in Lincoln‘, ‘drum kits in my local area’, and so on, so they can get started on their musical pathway as Holden did.

“We were together about two or three years,” he recalls. “This was around ’58 or ’59, maybe ’60. We had a singer, a sax player, piano-I was of course the guitar player. We played a lot of blues. A mix of everything you could think of: Ray Charles, Southern blues, James Brown-at this point, James Brown was just becoming ‘known.’ We had more of a ‘Big Band’ sound, just coming out of the ‘Swing’ band era, and into the ‘Rock’ band era. This was what was popular at the time I started my band.”

Setting themselves apart from the other Baltimore groups of the day, the Irridescents soon began to focus more on instrumental rock, with Randy’s guitar taking most of the leads. “My band was more rock or hard rock-oriented,” he explains. “To define that, you’d have to say Duane Eddy was ‘hard rock’ back then, comparatively speaking, but definitely a far removed stroke from the World War II swing bands.

“I wanted to do surf music,” he further elaborates, “because-well, actually it wasn’t called surf music yet. I liked the instrumental vein, and the Chuck Berry-ish kind of beat oriented stuff. We were together before Chuck Berry had his hits. We were doing a lot of really early rock’n’roll stuff.”

By late 1962 or early 1963 the Irridescents had scaled down to a three-piece surf instrumental combo, with Randy on lead guitar, Mike Port on bass, and Sonny Lombardo on drums. It was around this time that Joe Kooken, a.k.a. Jac Ttanna became aware of them. (Although Jac was Joe Kooken back then, we’ll refer to him in this article as Jac Ttanna.)

“I played softball, baseball, basketball, all that stuff, with all of my friends,” explains Jac. “Then one day I heard this amazing guitar playing. It was just amazing. It sounded like someone was playing a record, except I knew it was live. Me and my friends followed the sound, and here’s Randy in his front yard with a couple of other guys, playing what I think was a Silvertone guitar and Silvertone amp, or something like that, just sounding so good that I knew right away the guy was really special.”

Jac was in a band of his own at the time, playing instrumental rock, and it wasn’t long before he ran across Randy Holden again. “I was in Fred Walker’s Guitar Store, downtown Baltimore one day,” he recalls, “when this other guy was talking about this guy who learned three Ventures songs in one day. I was thinking, ‘Wow!’ I was into the Ventures. It turned out to be Randy. That’s when I really got interested in Randy. After I found out who he was, I discovered he was in a band called the Irridescents. I went down to a couple of their rehearsals. They were doing things like ‘Wipe Out,’ some Beach Boys songs, stuff like that, which no one in Baltimore did. Everyone in Baltimore was playing stuff like James Brown and Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland, and here’s Randy playing all this stuff. Stuff I really liked.”

At the time, plans were already afoot for the Irridescents to relocate to California. ” I had the dream of doing it around 1960,” says Holden. “I thought about going to New York… I was going to go to Germany, because I went to school with this guy from Germany, and he said they had this big rock ‘n’ roll scene going on there. He told me that they would love what I did over there, but I was of course, stone broke poor. I lived in poverty, ghetto style. The idea of getting money for an airline ticket was like trying to get a spacecraft to Venus!” he laughs. “So, I set my sights on California. That was the changeover. I was infatuated with the idea of the ocean, and warm sunshine for a change. I couldn’t stand it back East. The cold weather depressed me to the point of suicide. I just needed to get away from it.”

Jac was hanging out regularly with the group, and eventually got an invitation to join. “We were in a drugstore having Cokes one day, me, Randy and Mike. I mentioned that I was planning on leaving and going to Arizona, I was in school at the time, and they looked at each other and said, ‘Have you ever thought about California?’ I said ‘Well, not really,’ and they started telling me about California, everything’s happening and we need a rhythm guitar player. And right then I said ‘I’m in!’ That was it. From that time on we started rehearsing in my basement and we worked up a lot of material: Ventures, Chuck Berry, stuff like that. Randy didn’t want to do anything with vocals.”

Plans were made to leave for California in the fall of 1963. Sonny Lombardo, though, stayed behind in Baltimore. “He was a real good drummer,” says Jac, “but he was just too young to go with us. We packed up and left and figured we’d find a drummer when we got to California.”

“We scavenged together what we could to get out there, and just did it,” says Randy. “We traded in all our broken down vehicles for a VW bus, hauled our guitars and amps in it, filled it up, brought a box of food, and proceeded westward.”

CHAPTER 2: Surfin’ in LA

“We came out together in an old ’59 Volkswagen bus,” says Jac Ttanna, “loaded with equipment and everything we owned. That thing was so loaded we could only go about 45 miles per hour! It took us six days to drive out there. We hit town the day before John Kennedy was shot. We hit LA that night and woke up the next morning in a little room about a block from where I am living now. Everyone around was crying that John Kennedy was shot. Talk about your world changes.”

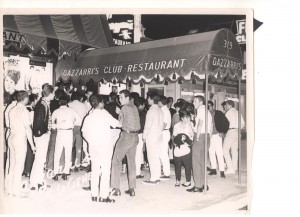

Out in California, they got themselves a drummer, Bruce Miller, and started playing the club scene. “It was weird because in Baltimore, 18 was the age you had to be to play in a bar,” remembers Jac. “When we got to California we found out you had to be 21. I was the only one that was 21, so we had to go to Tijuana and get phony ID’s until the rest of the guys turned 21. We were doing a lot of shows at the hip clubs around the area… We were already playing Gazzarri’s by the time Randy turned 21. Randy was underage for a couple of years that we were out here. We had Randy’s 21st birthday party onstage at Gazzarri’s!”

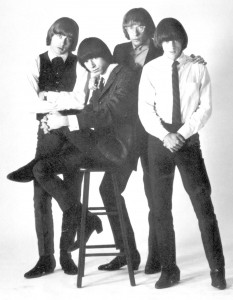

By 1964 they’d changed their name to the Fender IV. According to later drummer Michael Stuart the name change was motivated by a deal with the Fender Company that provided the group with a bunch of free equipment. It’s also possible they became aware of another surf group called the Irridescents, from Santa Barbara, who released a couple of cool singles before morphing into Thee Sixpence and eventually Strawberry Alarm Clock.

Soon after the name change the group signed a management deal. “We had two managers, named Bill Sone and Ozzie Schmidt, and they were surf guys too,” recounts Jac. “They discovered us in a little bar in the Valley call Spunky’s. We were playing as the Fender IV, but we were actually backing up PJ Proby. He had just changed his name from Jett Powers to PJ Proby. He would get drunk every night, but he sang good. He was fun to hang with. Anyway, he moved to Europe and became a big star, and meanwhile, Ozzie or Bill said ‘You guys are in the wrong place, you gotta come out to the beach.’ Basically what they did was set it up so we could play a set at this club, the Mirage. That then led to us doing several other shows at different clubs in the same area. We would play a set for free and the club would hire us. They were college bars and beach bars where people would come in from Malibu, people like Tuesday Weld, James Coburn, Caroll Baker, all these stars. It was quite a scene and we were just in town, only about six months, and we were the biggest thing on the beach.”

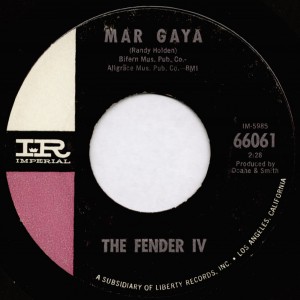

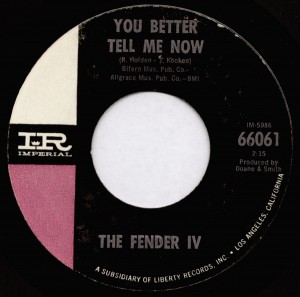

Bill and Ozzie knew music biz mogul Russ Regan, and before they knew it the group had signed with Imperial Records. The deal would result in two singles, both recorded at Gold Star in the summer of ‘64. The first, “Mar Gaya” b/w “You Better Tell Me Now” was issued in August. The A-side, composed by Holden, is a particularly ferocious surf track with some great, aggressive lead guitar work. “That was all Randy,” asserts Jac. “He wrote the songs, showed us all our parts. He basically taught Mike how to play bass and he taught me to play the guitar the way he wanted. He was the guy that came up with all those ska rhythms that were about 30 years before their time! Everything I played was down strokes. Everything.”

Although Randy had initially been opposed to doing any vocals, the flipside was a vocal track, written by Holden and Kooken, an odd but enjoyable mélange of Mersey and surf that in some ways pointed towards the band’s future direction. “We were kind of, in my view, always avant-garde for the time,” reflects Randy. “We didn’t play strictly surf music, although my orientation was instrumental, because I liked what electric guitars could do. Joe Kooken [Jac] insisted that we had to do vocals, because we were playing in bars, and people wanted to hear that type of thing. I was repulsed by the idea, but we did it anyhow. We sort of became fairly good at it.”

“Anything vocally you had to drag Randy in kicking and screaming,” recalls Jac. “Randy didn’t want to make any steps whatsoever vocally. He literally did not want to do any vocals. Finally we convinced him if wanted things to happen we had to do vocals. We did some Chuck Berry, then he did like the Beatles and the Stones.”

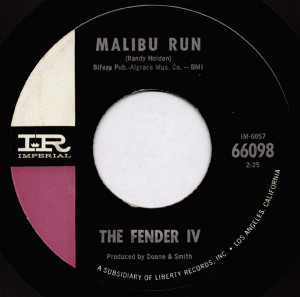

A second Fender IV single, “Malibu Run” b/w “Everybody Up” appeared the following February. The ultra-moody “Malibu Run” (a Holden composition, not to be confused with the Gary Lewis & the Playboys song of the same name) had originally been titled “Lonely Surf Guitar,” and features some terrific vibrato-laden guitar work by Holden, while the flipside is a wild, fast-paced instro.

Two more Fender IV tracks, likely from the same sessions, later surfaced on the Randy Holden Early Works ’64-’66 CD on Captain Trip, the rockin’ “Highway Surfer” and an odd but cool ska-beat surf number “Little Ollie.”

On November 1, 1964, the Fender IV played at the Long Beach Auditorium, backing Dick & Dee Dee on a bill that also included Jimmy Clanton, the Spats, and headliners the Rolling Stones, on their second US tour. “Dick [St John, of Dick & Dee Dee] had met Brian when he and Dee Dee toured Europe,” explains Jac, “and I guess that’s how they got the date. Dick knew us from a Casey Kasem show we did together. His musical director at that time was Mike Post, who went on to write the themes for Hill Street Blues, NYPD Blue, LA Law, and just about everything on TV these days.”

According to Ttanna, they crossed paths with the Stones several times back then. “They were jamming with a friend of ours at a place called the Action,” he recalls. “Joel Scott Hill was playing there with Lee Michaels and Johnny Barbata-the Joel Scott Hill Trio. Johnny later ended up with the Turtles, as you know. Anyway, they had jam sessions every Sunday and we went down and jammed, then Brian Jones came in and jammed, and Bill Wyman came in. We met them all that way. This was in 1964.

“We originally sort of ‘bumped into’ the Stones earlier when they did the Dean Martin show [Hollywood Palace]. We just happened to run into each other on Hollywood Boulevard. They were walking up the street and we were walking down the street. We all kind of just went ‘Whoa! Long hair!’ No one had long hair at the time, as you know. The Stones went ‘Who are you guys?’ and we said, ‘The Sons of Adam [N.B. In ’64 they were still called Fender IV]. Who are you?’ They said, ‘The Rolling Stones, we’re looking for clothes’ so we took them to the Beau Gentry. I think Brian got his red cords he wore on the High Tide cover there.”

CHAPTER 3: Rockin’ With Sir Raleigh

By the beginning of 1965, the Fender IV had moved away from surf music and were playing a lot of rhythm and blues, including plenty of early Stones material. They’d also got a new drummer, Keith Kester, who’d been hired after Bruce Miller received his draft notice. According to Jac, though, Holden and Kester didn’t get along, so they were on the lookout for a replacement.

They soon found one in Michael Stuart, a recent dropout from UCLA. In his book The Pegasus Carousel, Stuart describes seeing the Fender IV in action for the first time in January 1965, at the Mirage in Santa Monica. He was blown away by what he saw and heard. “Their sound was tight-knit and powerful, and professional, and they had total command of their instruments,” he writes.

Stuart was particularly impressed with Mike Port’s bass playing. “The bass players in the rock bands I had been with to that point played real simple patterns. One-note sonatas. Change the note every couple of bars, or so. The bass player in the Fender IV was banging out sophisticated runs that could only be described as ‘incredible.’ He was all over the fretboard, virtually defining the way an electric bass should be played.”

“Their hair was really, really long,” he continues, “and they had the stage mannerisms of a band that had been doing it long enough to be absolutely confident. And they had a following. The place was packed and the crowd was in the palms of their hands … they were dynamite.”

Between sets Stuart struck up a conversation with the band and mentioned that he played the drums. After an audition at Stuart’s parents’ home in Ladera Heights he was invited to join the band when they returned from a trip to the Pacific Northwest, where they were contracted to play a series of gigs backing future Buffalo Springfield drummer Dewey Martin. Martin, at the time, was the frontman for Sir Raleigh & the Coupons (sometimes spelled Cupons), and had scored a sizeable Northwest hit with a rocked up version of “White Cliffs of Dover.” The Fender IV had run into him at one of their LA bar gigs.

“We were playing a lot of beer bars at the time,” recalls Jac. “I don’t think we’d quite moved into Hollywood yet. Dewey came in when we were playing at one of these places, in a leather jacket. He looked like a rock star and bought us all drinks and said ‘Look, I got a hit record up in Seattle and I need a backup band, and if you guys will come up and play, we’ll do six songs, you do three, and I’ll do three. I’ll send you the three I want you to learn, and we’ll do it.’ And we said, ‘Sure, we’ll believe it when the tickets [to Seattle] get here.’

“A couple of weeks later the tickets arrived along with the records. One was an Adam Faith record, one was ‘White Cliffs Of Dover’ by Sir Raleigh & the Coupons, and the last one I think was ‘Georgia’ by Ray Charles. Whatever it was, we worked them up. We got there and the day of the concert we sat in the hotel room, went over the songs one time, then went onstage in front of 15,000 people. And it was great! We didn’t even know Dewey played drums. We came out onstage and we had our own drummer-at that time our drummer was Keith Kester. We came out onstage and there we saw another set of drums set up next to Keith’s set. So we started playing and all of a sudden the drums just got a whole lot better, they really kicked in. We looked around and there’s Dewey on the other set and I mean this guys can really play! It was really a kick to play with him as far as that goes.”

As Jac remembers it, they stayed up in the Pacific Northwest for about six weeks, playing shows with Sir Raleigh in Seattle and as far north as Alaska. “We were in Alaska with Sir Raleigh & the Coupons when Malcolm X got shot [February 21, 1965]. The coldest time in the history of Alaska!”

The group also backed up Dewey on some studio recordings. “While up there, he hired us to record some songs with him, and one of the songs he brought in was ‘Tomorrow’s

Gonna Be Another Day.’ If memory serves, I think the version we did with him actually came out a little better than the version we did later on our own [as the Sons of Adam]. Anyway we liked the song so much that we added it to our song list, and later recorded it ourselves. We recorded a few other songs with Dewey, so if you find anything other than ‘White Cliffs of Dover’ under the name of Sir Raleigh & the Coupons, that’s probably us.”

According to Alec Palao’s notes on Big Beat’s Northwest Battle of the Bands, Volume One CD, Sir Raleigh’s version of “Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day” was recorded in September ’64 with a backup band that included Future Flying Burrito Brother “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow, but Ttanna is certain that a version was also cut in February or March of ’65 with the Fender IV backing Dewey-and it certainly sounds like them. Jac is also thinks it’s likely that they’re on Sir Raleigh & the Coupons’ version of “Things We Said Today” (originally released on the Original Hitmakers compilation).

“The Sons of Adam [or Fender IV] did ‘Things We Said Today’ when we played live,” he recalls. “We had a huge repertoire. We played five hours a night and never repeated a song, and we threw in a few different songs each night. We also played five hours a night when we toured with Dewey-in Alaska we played from 9PM to 4AM; we did a lot of jamming on that one-and about an hour of that was Dewey’s songs. So we were doing a lot of songs.”

Jac adds an interesting footnote to the story: “We were making a lot of money with Dewey, and he wanted us to continue. Randy wanted no part of it. Dewey, who was from Canada, took me aside one night and told me that he knew of a guitar player we could get to take Randy’s place. He said this guy looked like Randy (true), sang better than Randy (also true), and could play better than Randy (not even close to being true). I told him I wasn’t interested, and we went back to LA. The guy he was talking about turned out to be Neil Young.”

“If Dewey hadn’t been drinking, we would have probably stayed and worked with him,” adds Jac. “He was a good singer and a great drummer, and a great entertainer. But the drinking was just totally out of control.”

CHAPTER 4: Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day

When the Fender IV returned from their Northwest jaunt as the Coupons, Keith Kesner was given his marching orders and Michael Stuart was installed on drums. The new lineup moved into a house together in Pacific Palisades and continued playing the bar scene, including Cisco’s in Manhattan Beach, the Beaver Inn in Westwood, the Warehouse IX in West LA, and the aforementioned Mirage in Santa Monica.

It was at the Beaver Inn that the group encountered Kim Fowley (an incident described in some detail by Stuart in his book). Fowley apparently liked the group but thought that the Fender IV was a “dogshit” name-which, truthfully, it was. He came up with a new name for the group on the spot: The Sons of Adam. “We just said, ‘That’s GREAT!’ recalls Jac. “So we were the Sons Of Adam from that day.”

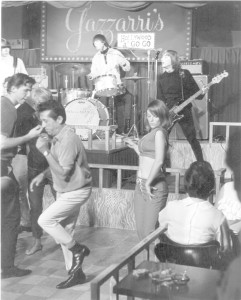

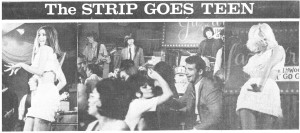

As the Sons of Adam they continued to build a following on the live circuit. As Michael Stuart remembers it, “we began to attract more of a hip crowd.” Their growing reputation led to a residency at a Hollywood club, Gazarri’s on La Cienega, and, later, its more high profile location on the Sunset Strip. Gazarri’s was frequented by a lot of TV and movie personalities, including Rick Nelson and his brother David, who stopped by regularly to dig the Sons, and at one point talked about signing them to the production company they were starting. That deal never happened, but one night the movie director Sydney Pollack caught the band and asked them to appear in a movie he was shooting, The Slender Thread, starring Sidney Poitier and Anne Bancroft. “We said, ‘Okay, we do lots of things like that,'” quips Randy.

The band’s scene, set in a nightclub, was shot on a soundstage at Paramount. “Actually, it took twelve hours to film three seconds,” complains Holden. “I hated it. It was absolute misery. They kept blowing this smoke that you have in movies-it’s beeswax. They set the beeswax on fire, and go around with these bellows blowing the smoke all over. It’s horrible to breathe that garbage all day long. It’s also horrible to lip-sync something repeatedly, over and over. Everyone is supposed to stay upbeat and happy. I wasn’t. So I wasn’t good at acting in the sense that I was supposed to be playing happy when I wasn’t happy. It was an interesting experience. However, I think I would have liked doing this if it moved, and had action, rather than trying to capture this one scene over and over again.”

Ttanna’s memories of the movie shoot are much happier. “I went out with one of the go-go dancers!” he grins. “The blonde one on the right side of the stage. She was Slim Pickens’ daughter. I never met him, but she was cool. I liked it a lot. I liked meeting Anne Bancroft; I liked watching the way they worked. I was fascinated by the whole process. I’ll tell you what Randy hated, it was all that smoke. They blew smoke in our face for 12 hours! After a while I was tired of that, too. But it was really fun. Randy was disillusioned with pretty much everything that wasn’t a concert in front of 15,000 people! That was all that Randy wanted and everything else was a downer.”

The band’s scene in the movie is pretty great, as the Sons rock out onstage, Jac in his shades, and Randy with his guitar slung real low. “I’ve played it low since the time I was in the Irridescents,” explains Randy. “I have to admit, I think Chuck Berry was the influence there. When he did the duck walk with the guitar on the ground, I just went ‘YEAH! The guy is cool!'”

As for the high-energy guitar instrumental they’re miming to: “That wasn’t us!” confesses Jac. “We recorded a whole bunch of stuff and apparently none of it worked out. They actually recorded us live, but something happened where the recording was distorted or it got lost so they got some studio guys to do that track. It was probably Glen Campbell.”

Apparently disenchanted that the deal with Imperial didn’t take them further, the band had by this time broken off ties with Bill Sone and Ozzie Schmidt. They next entered into an unwritten agreement with Dick St John (of Dick & Dee Dee) and Mike Post. St John and Post recorded some demos with the band, but according to Michael Stuart they didn’t sound right at all, because “like a lot of the people who had designs on the future of the Sons of Adam, Dick St. John and Mike Post kept trying to turn the group into something we weren’t, and something we knew we could never be.” The relationship was abruptly terminated by Randy, much to the consternation of St John in particular, who got his ‘revenge’ on the group shortly afterwards by berated their talents onstage when they backed up Dick & Dee Dee at a Cinnamon Cinder gig.

“He ‘got even’ with us, I guess, in his own mind, at least,” writes Stuart in his book. “Except that several regulars came up to us after the set and said stuff like, ‘What the fuck was wrong with that asshole? You guys were playing it right.’ I mean, it was our audience. The Sons of Adam were the mainstream entertainment at the Cinnamon Cinder. Dick and Dee Dee were an ‘oldies’ group-visitors from the past.”

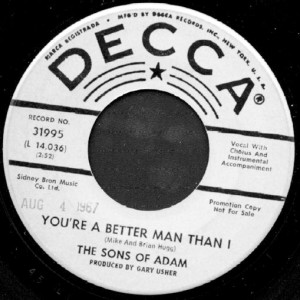

They met their next manager, Dick Martinek, through Bobby Sherman, then a regular on ABC-TV’s Shindig! Martinek was a competent and well-connected manager, who was also handling the Surfaris. The Surfaris were signed to Decca Records at the time, and were working with staff producer Gary Usher. Martinek persuaded Usher to come see the Sons of Adam play live, and the producer was impressed enough to bring them in for an audition, which subsequently resulted in them signing a six-month contract with Decca.

The group recorded their first single, with Gary Usher producing, in mid-October 1965. Interviewed by Stephen McParland for his excellent Usher biography, The California Sound: An Insider’s Story, the late producer admitted that working with the Sons of Adam was a somewhat frustrating experience. “I could never capture that brightness, nor the excitement they had on stage,” he told McParland. “Their own songs were also good, but translated onto disc they needed more color, more production, yet the group seemed not to want that. They weren’t into overdubbing, and they seemed to be uncomfortable around other musicians. I was always pushing for percussion, guitar overdubs, organ or whatever color I could give them, but they simply wanted it four-piece, crude and raw, and I was not used to that at all!”

Ultimately, “Take My Hand,” written by Jac and Randy, came across as something of a compromise: a mix of the rough and ragged chug of the Stones and the smooth melodic vocal sound of the Beatles or the Byrds. The record sounds great today, but at the time neither the band nor the producer was satisfied.

“I liked Gary,” states Holden. “He was an interesting guy. As far as what we were doing instrumentally, he understood. So when we recorded with him, he had a good feel for it. However, vocally, he tried to turn us into the Byrds, which we were not.”

According to Usher, Chuck Girard of the Hondells was brought in to bolster the high end of the group’s harmonies, while the producer rattled the tambourine. Ttanna, though-who sings lead on the song-credits the harmony work to Michael Stuart. “He was a great singer,” says Jac. “Terrific.”

On the flipside was a new version of the song they’d cut earlier with Dewey Martin, “Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day.” “All three of us sang in unison on that,” remembers Jac. “I don’t think there was really any harmony or anything on that. That’s the way we did it live.” Stuart’s drums are particularly thumping on this track, and Holden’s two hot guitar breaks take their cue from Keith Richard’s style, but Ttanna is probably correct in his assertion that the earlier Sir Raleigh version has the edge.

Released in December 1965, the single tanked, after receiving little or no promotion from Decca, who were sinking most of their advertising budget into the Who at the time.

Reportedly a version of “Hey Joe” was taped at the same sessions, or shortly thereafter, and at one point was in contention as a follow-up release. According to McParland’s book, that notion was quashed when the Surfaris announced their intention to record the song, too. Usher vigorously objected, but his superiors in New York gave the go-ahead for the Surfaris’ “Hey Joe” over the Sons’ version. As it happened, the Surfaris recorded a pretty decent version, but according to Usher it wasn’t nearly as good as the version he’d already cut with the Sons. “Compared to the Surfaris the Sons of Adam were total professionals,” he told McParland. “There was actually no comparison. They could play the hell out of their instruments and they fitted the new image perfectly. They were talented, tight and L-O-U-D!”

Interestingly, both the Surfaris and the Sons of Adam included future members of Love (Ken Forssi and Michael Stuart, respectively)-and Love, of course, would also record a version “Hey Joe.”

While the Sons of Adam’s version of “Hey Joe” remains unheard, several other outtakes appeared on the aforementioned Early Works CD, including two Kooken/Holden compositions and a fine version of the Zombies “You Make Me Feel Good.” “I liked the Zombies a lot,” says Holden. “They had a nice musical feel about them.”

The two original songs, “Without Love” and “I Told You Once Before,” are both moody minor key pieces in the early Beau Brummels mode. Characteristically, Randy is dismissive of these early efforts. “At the time I liked them,” he admits. “When I listen to them now, I say to myself, ‘That’s kind of interesting,’ but I really don’t know much else what to think of them. There wasn’t any thought put into them. The lyric lines were whatever popped into my head. In other words, I didn’t have a clue what I was writing!”

More bad luck followed at the turn of the year, as the Sons came close to scoring a regular slot on national television-only to have the opportunity snatched away at the 11th hour. “We were booked on Shindig!” recounts Jac. “We were actually supposed to take the Righteous Brothers’ place on the show. Bobby Sherman used to come and sit in with us all the time at Gazarri’s. He just loved us. Anyway, he booked us on Shindig! to replace the Righteous Brothers. So we went down there-the Shindogs were there and everything-then the show got cancelled! So that didn’t happen. It was one thing after another that was supposed to happen and didn’t. That’s the way it went. Every time we were going to take off, something would happen.”

Michael Stuart remembers the Shindig! debacle a little differently. “Bobby Sherman made arrangements for us to appear on Shindig. He told us, ‘You guys will be paid AFTRA scale of around a couple hundred bucks each, but the network expects you guys to kick those checks back. All the guest acts do it.’ So we said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ We just wanted to be on network TV.

“A few nights before the scheduled taping, Bobby shows up at Gazzarri’s at the break, walks up to the stage with his arms spread and a confused look… ‘What happened?’ We said ‘What?’ He says, ‘Your manager showed up at ABC and said you guys weren’t gonna kick the checks back to the network, so you guys are off the show.’ That’s all. There was no taping with the Shindogs that I can recall. Maybe I blanked it out.”

Having blown the band’s big chance for national TV exposure, Martinek next booked them into a sleazy topless bar near LAX. “He had been told not to ever book us in any kind of a bowling alley topless bar loser dump ever,” laughs Stuart. “but he went right ahead and booked us for that exact kind of gig anyway.”

Needless to say, the Sons and Martinek parted company soon afterwards.

CHAPTER 5: Saturday’s Sons

Although their recording and television careers didn’t seem to be going anywhere fast, the Sons of Adam continued to be a popular live act, boosting their profile on the Hollywood club scene with packed-out shows at Gazzarri’s and the Whisky A-Go-Go. They’d also begun hanging out with another hot band on the scene, Love, whose performances at Bido Lito’s were already the stuff of legend. One night, Arthur Lee invited the Sons to play a guest spot at Bido Lito’s, and the band reportedly brought the house down (an incident described in some detail in Michael Stuart’s Pegasus Carousel book).

In March 1966, the Sons of Adam went into RCA Hollywood to record a new single. Although Gary Usher was again producing, this time the engineer was Dave Hassinger, famous for his work with the Rolling Stones. With Hassinger’s help the band were able to get much closer to the sound they wanted to capture on tape. “Even Randy liked him!” jokes Jac. “We did [“Mister You’re A Better Man Than I”] and “Saturday’s Son” exactly the way wanted.”

“Mister You’re A Better Man Than I” was brand new (it had first appeared in the States the previous month on the Having A Rave-Up With The Yardbirds LP) but was already one of the biggest crowd pleasers in the group’s live set, so it was a natural choice for a single. “The Yardbirds were a great band, and I liked the song a lot,” says Randy. “I also loved Jeff Beck, he was a great guitarist. Of course we had to play a lot of cover songs, because we worked the club circuit for a living. We’d play clubs five hours a night, seven days a week. That’s how we’d stay alive. You could not go about playing all of your own material, so you just threw in what you could, when you could.”

The Sons’ version, with Mike Port singing lead, is almost the equal of the Yardbirds’ classic recording, with a truly volcanic fuzz guitar break by Holden. The flipside, “Saturday’s Son,” was written by Lou Josie, a.k.a. Jim King, an associate and occasional songwriting partner of Usher’s. It’s another killer track, with cool ‘bad seed’ lyrics (“13th child of the 13th child, born in the back streets and growin’ up wild”), manic fast-paced drumming and, of course, some scorching lead guitar work. Jac sings the lead on the bridge and chorus while the rest of the group harmonizes with him on the verses.

With a powerful single in the can, the band felt confident their fortune was about to change, but then word came back from New York that the executives at Decca were concerned about one of the lines in “Mister You’re A Better Man Than I.” “Decca gave us a hard time about the lyric ‘The color of his skin is the color of his soul,'” explains Ttanna, “and they wouldn’t put the record out because of this line, which is so lame. Then finally Terry Knight & the Pack put it out. Then after that Decca decided it was OK to put it out. Terry Knight had already taken off with it by then, so we lost our chance of possibly having a hit record.”

The grossly inferior Terry Knight & the Pack version saw some low-level national chart action in May, while the Sons of Adam release was delayed until July.

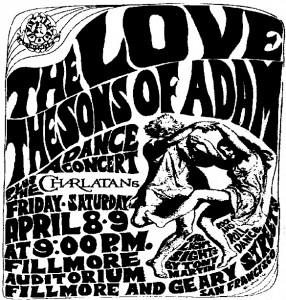

Before then, the Sons began working with a new manager, Howard Wolf, “a terrific manager,” according to Michael Stuart, who worked out of Hedda Hopper’s old office on Hollywood Boulevard. Wolf began booking the group more out of town gigs, mostly up in the San Francisco area, where a big new rock scene was just beginning to blossom. On April 8-9 they played a memorable two-night gig at the Fillmore in San Francisco on a bill headlined by Love, whose first album had just been released by Elektra.

Michael Stuart tells the story of that night in Pegasus Carousel: “After a while, it was time for the Sons of Adam to go on, and we were dynamite. We blew the crowd away. We had it working just like the night we did the guest shot at Bido Lito’s. An ovation after every song. That old thing about playing a brand new room where nobody has ever seen you before was working full bore. You always get up for it. By the time we had finished our set, Love had arrived. We were on our way back up the stairs to the dressing room when we bumped into Johnny [Echols] and Arthur coming down. We nodded and said ‘Howdy,’ and Arthur nodded back and said, ‘Great set, man.’ Then Love went on stage and they blew the audience away, just as we had done. Like the old time, ‘Battle of the Bands.’ It was a hell of an ‘all LA’ show.

“Around a year later, when I was playing drums with Love, Bryan [Maclean] would tell me, ‘Man, when we walked into the Fillmore to do our set and saw you guys on stage, we knew we had our work cut out for us. It was like, you belonged up there and we didn’t. It was your place. We had to try and take it back.'”

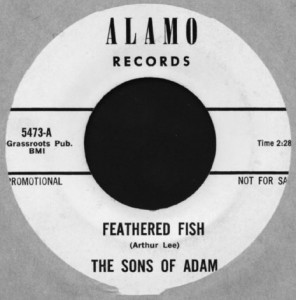

While Arthur Lee was fiercely competitive by nature, he evidently liked the Sons of Adam a great deal, going so far as to offer the group first pick of a batch of new songs he’d just written. According to Jac, Arthur showed the group three songs: one was “Feathered Fish,” another was a song about a girl called Mary (Jac can’t remember the title), and the third was “7 And 7 Is.” Michael Stuart remembers just “Feathered Fish” and “7 And 7 Is.” “Anyway, Randy didn’t like any of them except ‘Feathered Fish,'” says Ttanna, “although I thought it was the weakest one.”

Randy remembers only “Feathered Fish”: “He came by where we were rehearsing one day and said he had a new song, and we could have it if we wanted it. So I said, ‘OK, let’s hear it.’ I thought it was a pretty good song. Arthur was a pretty creative writer in some respects back then, but an impossible guy to work with.”

The group added “Feathered Fish” to their live repertoire, and would eventually record it for their third single. In the meantime, as the Sons continued to wait for Decca to release “Mister You’re A Better Man Than I,” Arthur took “7 And 7 Is” back to Love and it was released as their next single in June 1966. It was a monster smash hit in LA and reached #33 nationally. By now, the rest of the band must have been starting to question the judgment of their leader.

For his part, Randy was becoming increasingly frustrated with being forced to play endless cover versions and having club owners constantly telling them to turn down their amplifiers. “I liked playing LOUD,” he stresses. “Excitement generated like heat. Of course, we were always told by club owners to turn down, regardless that they were making fortunes off of us. Lines of people waiting to get in.”

Randy had also got married, as had Mike Port, and according to Jac that brought all kinds of outside pressure to bear. Worst of all, the wives began interfering in the band’s business and questioning every move they made. “The wives were getting disillusioned,” he remembers. “They thought they were getting married to guys that were on the rocket going to the top, and they’d say, ‘This is wrong, and this is wrong, and this is wrong…’ And they didn’t know anything. So there was some bad dissention within the ranks. Before it was the four of us against the world.”

Things came to a head between Randy and the others in early August during one of their excursions up north for a short run at a club in the San Jose suburb of Los Gatos. “We did a show in San Jose,” recounts Jac, “and it was in a small club. It was terrible; you really couldn’t play [loud enough]. Anyway, Randy got so bummed out with this-and Randy was bummed out anyway, Randy was just becoming impossible-he literally turned his amp down where you couldn’t hear anything at all and we became a trio. He’d lean on his amp and put his ear on the speaker. This went on for five hours.

“Mike Port and Mike Stuart were there the day before,” he continues, “and all these musicians, like Jackie DeShannon, the Airplane, Janis Joplin were all hanging out up there. Mike Port and Mike Stuart saw this guy Craig Tarwater there-he was an amazing musician, amazing technique. They were already tired of Randy. Unbeknownst to me, they were already thinking of getting Craig into the band, because Randy was literally impossible at this point. They talked to me about it and I said, ‘No way! He is the band. The band lives and falls with Randy, that’s just the way it is.’ Then that very night, Randy pulled that thing, and, over the course of the week, Randy didn’t get any better at all, and I finally said all right.”

“To begin with, it was just a bad time for all of us,” reflects Michael Stuart. “We had been cruising along in high gear, playing all these great gigs in legendary venues and doing the movie (Slender Thread). Then we sorta downshifted and got stuck in neutral and lost our direction, and then everything became a struggle for some reason. Maybe because we had been around for a while and no hit record. Then here we were playing a club nobody had ever heard of in San Jose in a depressing environment. “I remember one day it was payday at this dive and the club owner gave us some song and dance why he couldn’t pay us right then,” he continues, “and it was like the second or third time it had happened. So, Mike Port took a hit off his cigarette and made a sarcastic comment about the delay paying us our bread, and the dude’s henchman kinda stood up and looked at Mike real mean and said like, ‘Well, maybe if you keep bitching about it I’ll kick your ass.’ And Mike looked at him for a second said, ‘I’ll bet you could, too.’ Because I think he mighta had a gun, so Mike backed down. Anyway, things were bad. Depressing as hell. We just kinda fell apart.”

Rather than confront Randy directly and fire him from the group, the others ended up taking a more passive-aggressive approach. “What we did was tell Randy we wanted to play stuff he didn’t want to play-Byrds stuff and things like that,” admits Jac. “Probably the only time I ever lied to Randy. So we said we’re gonna go on and do this, and we picked up Craig.”

Randy remembers the split similarly: “The band decided they wanted to turn down and play songs more like the Byrds. Well, you know, I just can’t do that. That’s kind of like I’d have to lie to God to do that.”

CHAPTER 6: LOVE Is All You Need

Craig Tarwater began his professional musical career with the Randelas, based out of the town of Walla Walla, Washington. “The band started out in 1964 as a fully professional working band,” he remembers. “We played all of the pop hits of the day that we were capable of and worked all over the Pacific Northwest for two years.”

They were all excellent musicians, but Tarwater’s lead guitar playing was one of their standout features. According to Northwest music historian MD Brownsworth (on the website pnwbands.com): “The guitarist, a redhead named Craig Tarwater, was almost a savant on his instrument. His command of the guitar was remarkable; some even described it as ‘frightening.’ When other guitarists were noticed in the crowd the Randelas would delight in calling an instrumental tune written by Tarwater named ‘Hangnail,’ a blistering guitar tour de force. The other guitar players would slink away into the darkness to reexamine their choice of instruments.”

When singer Jeff Hawks joined in 1965 they changed the band’s name to Hawk & the Randelas, and around early 1966 they cut a single for the Riverton label featuring two original songs, “One Like Me” and “I Don’t Wanna Know.” In May 1966 the Randelas relocated to San Francisco, by which time Rick Dey (who wrote the Paul Revere & the Raiders smash “Just Like Me”) was a member. Soon after the move, though, the band split up. Hawks, along with bass player/songwriter Ron Overman would go on to join Don & the Goodtimes. Meanwhile, Tarwater and Dey began a new project together, along with Val Garay, but Craig is unsure as to whether this band ever had a name.

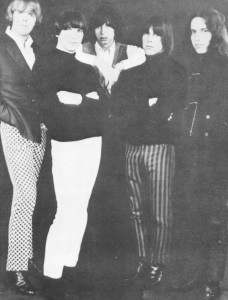

Hawk and the Randelas, 1966. L to R: Kirk Holmquist (electric piano and Vox organ), Roger Huycke (drums), Ron Overman (bass), Jeff Hawks (lead Vocals), Craig Tarwater (guitar).

By the summer of 1966, Craig was getting by playing guitar behind Jackie DeShannon and Lee Michaels, and that’s when he ran into the Sons of Adam. “The Sons were working in a club in Los Gatos, California,” he remembers, “and that’s where they saw me playing with Jackie DeShannon and Lee Michaels. They thought I was good enough, so they hired me as Randy Holden was moving on.”

Michael Stuart remembers one of their first meetings with Craig: “We had hung out a little at the club and he says one night, ‘Come on over to my apartment tomorrow,’ and he gave us the address. So Jac and I went over the next day and one of his bandmates comes to the door and we say, ‘Is Craig here?’ and the guy says, ‘Oh yeah, he’s in the bedroom asleep, but you can go ahead in and wake him up, he’s expecting you.’ So we went on down the hall into the bedroom and looked in, but no Craig anywhere. We go back to the dude in the living room and say, ‘Hey man, Craig’s not in there.’ He says, ‘Oh yeah, he is. He sleeps in the closet on the floor.’ So Jac and I went on back in and opened the closet door and there he is. Sleeping. I think he said later he could have had the bed but he liked sleeping on the floor in the cozy, cozy closet.”

With his undeniable skills as a guitar player, Craig seemed like the perfect replacement for Randy Holden, but that didn’t prove to be the case. Somehow the chemistry just wasn’t there. “We went down to LA with Craig,” recounts Jac. “We had our first rehearsal and I knew right away we’d made a horrible mistake. It wasn’t that Craig couldn’t play; he just didn’t fit in. The fact of the matter is: every guitar player I’ve ever worked with was brilliant. Kent Henry was brilliant, too [Jac would later form Genesis with Kent, who eventually ended up with Steppenwolf]. Craig and Kent both had more theory, more knowledge than Randy, and actually a little better technique, but Randy was the only one who could just tune into the cosmos somehow or other and just create this amazing thing that happened where you just go off to this other level. Most bands get there once in awhile, we got there every night. There was nothing else like it. With guys like Craig and Kent we never really reached that level. Craig was even harder to work with than Randy!”

The Sons Of Adam, ca. Late ’66/early ’67. L to R: Mike Port, Craig Tarwater, Randy Carlisle, Jac Ttanna.

“Craig was a great technician,” agrees Michael, “but Randy wasn’t only the backbone of the group, he was one of the all time great guitarists of the sixties or any other decade, for that matter-including now. His skills are unparalleled.”

Arthur Lee had been trying to persuade Stuart to join Love for some time, but Michael had stayed loyal to the Sons. Arthur was persistent though, and by the late summer of ’66 the time seemed right to make the move.

“Arthur used to come over to the band house and take Michael for a ride in his [Porsche] 912,” recalls Craig, “and after a few weeks of riding he announced that he had been given an offer he could not refuse. Michael was always a gentleman and honest with everyone.”

“For the last few months, the Sons of Adam had been in a kind of holding pattern,” he explained in Pegasus Carousel. “No movies, no modeling assignments, our record deal had gone flat, and lately we had found ourselves playing the same old clubs over and over. But more importantly, our lack of a really outstanding lead singer was becoming more of a noticeable detriment than ever before. It seemed to be something we simply couldn’t get past … The times were changing, competition was getting tougher and fuses began to grow short at the Sons of Adam’s rehearsals … an offer from Arthur to join Love was beginning to look tempting.”

“Love was after him like crazy because their drummer was not making it,” remembers Jac. “Love already had an album out and it looked like they were going to be big stars, so Arthur said that he wanted Mike to come over and play on the sessions. And of course he really gave Mike a lot of money, a lot of drugs and stole Michael away.”

For Michael, drugs were not part of the equation at all-yet. Apart from an occasional joint, he never touched them. In the end, his decision was based on the music, and the tipping point came when he flew up to Fresno with Love, at the invitation of the band’s unofficial manager Ronnie Haron.

“At the first gig on Friday night, the atmosphere was filled with the kind of magic you expect when a great rock group comes to perform in a town like Fresno,” writes Stuart. “As soon as we walked in, we knew the audience was pumped. Love indeed had that something special which almost always captured the imagination of any audience. A unique style and power that foretold a level of future success with virtually no limit. I told Ronnie, later that night, that I would give my notice to the Sons of Adam when we got back home.”

Michael Stuart, of course, went on to play on Love’s classic Da Capo and Forever Changes albums. For a more detailed account of that period, the book Pegasus Carousel is highly recommended.

CHAPTER 7: Show the World

Meanwhile, after the departure of Michael Stuart, the Sons of Adam soldiered on for another nine months with a new drummer, Randy Carlisle. “We played the Whisky, the Hullabaloo, Bido Lito’s, and we also worked a lot of small concert venues, which were all provided by Casey Kasem, who promoted on the side along with his DJ duties,” remembers Craig.

“Randy Carlisle had a lot of potential,” says Jac, “but never could quite get his act together, which he’d be the first to admit, if you talked to him now. I played with Randy recently and he plays really good now! He was just getting started. Things were just never the same.”

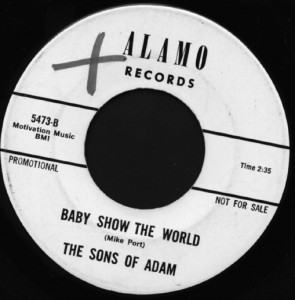

The Sons continued to be primarily a covers band. “The group did a lot of Yardbirds tunes,” recalls Craig, “and I think the originals were limited to ‘Feathered Fish’-original to us, even though it was authored by Arthur Lee-and a tune written and sung by Mike Port [“Baby Show the World”].”

Around the spring of 1967, the band recorded their third and final single, for Alamo Records, a small label run by a strange character by the name of Tony Alamo. Born Bernie Lazar Hoffman in 1934 in Joplin, Missouri, Alamo relocated to Los Angeles, where he changed his name to Marcus Abad and reportedly served jail time on a weapons charge. After converting from Judaism to Christianity, he changed his name to Tony Alamo, and along with his new wife Susan Lipowitz founded a street ministry, passing out religious tracts on Hollywood Boulevard targeting primarily drug addicts, prostitutes, teenage runaways and street hippies. Alamo would eventually expand his ministry into a large and hugely controversial religious organization, the Music Square Church (later called the Holy Alamo Christian Church and Tony Alamo Christian Ministries). He served federal jail time in the 1990s after a series of scandals, one involving the missing remains of wife Susan, who died in 1982.

In 1967, though, Alamo was still an unknown hustler, working several angles on the fringes of the music industry, in addition to his street ministry. None of the band members remember the exact circumstances of how they became involved with the fast-talking hustler, but the deal was for a one-off single, with the Alamo as producer.

“Tony Alamo seemed to me to be someone with a different agenda than ours,” reflects Craig. “He insisted we change some lyrics on one of the tunes. I don’t remember if we did or not.”

The two songs the band elected to record were the song Arthur Lee had given them the previous year, “Feathered Fish,” and a Mike Port composition, “Baby Show the World.” By all accounts, the session, at a cheap, no-name studio, was something of a disaster. “He took us into this studio, and he was going to be the producer,” relates Jac, “and this engineer didn’t know anything, and he didn’t know anything. We’d be playing one thing, then they’d play the tape back and it would just be this horrible sounding mess. We were so incredibly discouraged. Fortunately at the end of the session, Lee Michaels came in to see what was going on. He took me aside and said, ‘This sounds like shit. Do you want me to take over?’ I said, ‘Yeah, would you?’ So he went in there and he got what we ended up with on the record, which was way, way better than what we were getting [before]. It was Lee who came in got everything sounding right after it became apparent that Tony didn’t have a clue.”

Despite all the problems in the studio, the single turned out rather well. “Feathered Fish” is a great garage-psych track with some fine group harmonies. To this day, it’s probably the best-known Sons of Adam track, due to its appearance on Pebbles Volume 2. Jac, though, considers the recording a major disappointment. “The reason I didn’t like it was that it was half of what it was when we did it live,” he explains, “and we actually did it better with Randy than we did with Craig. That’s no reflection on Craig’s guitar work, which was the best thing on the record. I just felt like we did it better as a unit with Randy and Mike Stuart.”

The flipside, “Baby Show the World,” gives some indication of the ferocity of the group’s live shows, the excitement stoked to the max by Mike Port’s screaming lead vocal and thunderous bass line, while Craig Tarwater lays down some blazing lead guitar work. Unfortunately, though, “Baby Show the World” would be the Sons of Adam’s last stand.

As Jac remembers it, the group’s last gig was in LA on June 18, 1967. The split was precipitated by Tarwater leaving to join the Daily Flash. “We lived across the street from Jon Kelihor and Don MacAllister of the Flash,” says Craig. “Don saw me playing and said I was the replacement he wanted for Doug Hastings. I credit Don entirely for giving me my musical direction from that point on.”

CHAPTER 8: Other Half

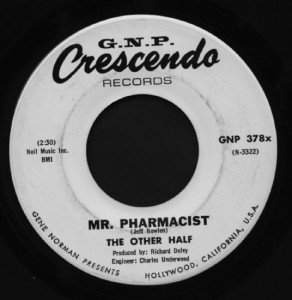

After parting ways with the Sons of Adam in the summer of ’66, Randy Holden wasn’t sure what his next move would be. “I really didn’t know what I was going to do,” he says. Before too long, though, he ran across a group that interested him, the Other Half.

“They were a club band, and somebody told me they needed a guitar player,” remembers Holden. “I went to hear them, and what impressed me about them was that they wrote their own music. It was difficult for the Sons of Adam to get together to write music. We always did it onstage. I did not want to play everyone else’s music [anymore].”

Randy joined the Other Half around late August of 1966, completing a lineup that also included lead vocalist Jeff Nowlan, rhythm guitarist Geoff Weston, bass player Larry Brown and drummer Danny Woody. In September 1966 the group released their first single, the blazing “Mr Pharmacist” b/w “I’ve Come So Far” on GNP-Crescendo, produced by Richard Delvy of the Challengers. Two more Delvy-produced cuts, “I Know” and “It’s Too Hard”-both excellent-later appeared on a rare French EP.

THE OTHER HALF, ca. late 1966. L to R: Jeff Nowlan, Larry Brown, Randy Holden, Danny Woody, Geoff Weston.

One of the Other Half’s biggest gigs was at the first Elysian Park Love-in on Easter Sunday, March 26, 1967 in Los Angeles. “One hundred thousand people showed up,” remembers Randy, “painted, freaking out, all stoned out of their bloody minds. It was a madhouse of chaos, and I didn’t want to play, because nobody was conscious!” he laughs. “I was pretty angry. It wasn’t a love-in for me, it was more of a ‘hate-in’!”

The band also appeared on the first episode of the TV series The Mod Squad. “As I recall, the producer of the show saw the band play, and asked us to be on the show,” says Randy, “same as with Slender Thread. I don’t remember much about it. I do remember you spend a lot of time on a set waiting. Typically twelve hours a day, waiting. A bit boring-and all the worse because you aren’t really playing, you are lip syncing, so you have to feign excitement, if there is any. Usually I didn’t know what was going on, e.g. when we were filming or when we weren’t in the scene, yet we lip synced over and over and over, which can really get dull. In retrospect I probably should have jumped up in the air and down on my knees, and all the showbiz stuff, but then the producer probably would have thrown me off the set,” he laughs. “And I don’t know how many times my knees could have taken it-probably not long enough to last the day!”

In 1967 the Other Half located to San Francisco. Subsequent Other Half releases, recorded at Golden State Recorders, appeared on the Acta label, beginning with the sensational Yardbirds inspired rave-up “Flight of the Dragon Lady” single in February 1967. Three more 45 releases followed, along with a great, but severely under-appreciated self-titled LP in May 1968, loaded with incendiary psychedelic hard rock, and including a version of the song Arthur Lee had given to the Sons of Adam, “Feathered Fish.” (Hopefully, in the future, we can do the band full justice with an entire in-depth story.)

Randy himself is not particularly satisfied with the Other Half’s recordings, feeling they don’t capture the power or the all-important visual element of the band’s live performances, for example on the track “What Can I Do For You.”

“I think you have to split the way you’re thinking about [that song],” he explains. “You’re thinking about it in terms of a recording that was done that you hear. But you’re absent of another whole aspect of what it was: the visual aspect. Live, I would be jumping off stage, jumping up in the air, falling on my knees, and hitting these crazy notes. So, if you don’t have the theatrics to go along with the sound, you don’t know what it is! It was a theatrical performance.”

“I had the wrong guitar for what I was trying to do,” he further elaborates, “and the wrong amplification. I had a very difficult, next to impossible time trying to do it. I used a Jaguar, what I needed was a Stratocaster. I used a couple of Fender Dual Showmans. That was not the right setup. I was trying to get sustain, but [also] powerful, emotional melodic composition, but I didn’t accomplish any of the melodic composition. I couldn’t get what I wanted in the studio, because the amplifiers wouldn’t do what I wanted them to do. I realized I had the wrong guitar, and the wrong amplification, so I was struggling. When I had all of the amps plugged in onstage, I was much closer to getting the sustained notes, and playing melodic lines to some extent. Live, this song was a whole lot of fun!”

Holden parted ways with the Other Half in 1968. “I just didn’t like the direction of the band at that point,” he says. “And I think there was a lot of conflicts. Personal conflicts. Musically, it was always a struggle.”

In 1969 he joined Blue Cheer, replacing Leigh Stephens on lead guitar. “Blue Cheer came on the scene while the Other Half was already playing in San Francisco for a year or so,” he remembers. “Then Blue Cheer came out. They were the loudest band of the times, with one exception-that when I would do my solo onstage, I was the loudest guitarist in the world. So, they took an interest in me, and we had become mutual friends.”

He wound up playing on one side of Blue Cheer’s New! Improved! album and playing a tour of the US and Europe before quitting the band in 1970, frustrated with their financial arrangements, as well as the other members’ escalating drug problems.

He went on to make the highly regarded Population II album, which was released on the tiny Hobbit label in 1971. After that, he quit the music business altogether-“I slammed an iron, steel and concrete door on it”-and moved to Hawaii.

“I moved to Hawaii when everything went bankrupt,” he recounts. “The record company wouldn’t release my album, and everything crashed. The album, to my knowledge, never came out. I was surprised to hear of it in 1993! It was a very frustrating time. It was very depressing. The equipment all disappeared one day. I never had any money to do anything, and I just threw my hands up in the air. I had to take a reality check, and I decided that I had to ‘blank out’, and to think about nothing. I couldn’t deal with all the negatives. I wasn’t able to accomplish what I wanted to do. Brick walls were in front of me. I kind disappeared off of the face of the earth.”

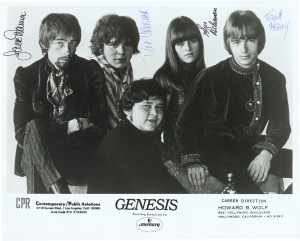

CHAPTER 9: Genesis and Beyond

After the breakup of the Sons of Adam in June of 1967, Jac Ttanna remembers, “I spent the summer sitting in vacant houses.” He and Mike Port began putting together a new group, with singer Sue Richman. “I thought, wouldn’t it be great to get a sort of Mamas & Papas vocal sound with a sort of Cream background! So that was what that was all about.”

The group was to be called Genesis (not to be confused with the famous English band, of course). “Next I found Bob Metke, who was really a good drummer, then Kent Henry,” recalls Jac. “At the time Mike Port was going to play bass. That would have been good, but then he didn’t want to play bass anymore. He’s the guy that got into the Byrds-he got into it to the point where he wanted to play guitar and write inspirational songs. He took too much LSD actually. He was never quite the same again. Literally there were some people that never came back. He was one of them.

“He went back to Baltimore,” he continues, “married somebody, lived with her for 25 years. Apparently she just died. He’s the manager of the theater in our old neighborhood for the past 25 years as well. To me this is one of the great wastes of our time. I mean this guy was ‘the man’ on bass the whole time that we were actually the hottest band in Hollywood. He was ‘the guy,’ the guy everybody wanted. A great bass player, great singer, good showman, good looking. He was a large part of what were as successful as we were. We all contributed, but Mike contributed hugely. For a guy to just walk away from all that, it’s really a shame.”

After Mike Port left, Kent Henry brought in Freddie Rivera on bass. Henry and Rivera previously played together with Eddie James & the Pacific Ocean. “Eddie James was the first incarnation of Edward James Olmos, the actor,” explains Jac. “He tried to break through with a couple of different bands before finally making it as an actor.” Kent Henry’s replacement in the Pacific Ocean was none other than Craig Tarwater.

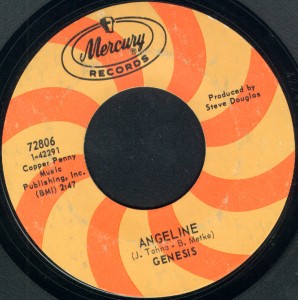

Like the Sons of Adam, Genesis were managed by Howard Wolf, who succeeded in getting them a deal with Mercury Records. Their late 1967 single “Angeline” saw some regional radio airplay (including in Rochester, NY) but failed to chart nationally. A full-length album, In the Beginning, followed in 1968, but by 1969 the group had split up. At this point Jac gave up playing in bands and signed on as Lee Michaels’ road manager. In 1975 he was hired as Canned Heat’s road manager. “I did that for 18 months,” he says. “That’s when I really got turned onto the blues. All the guys in the band had great collections.”

These days he’s playing again. “I’ve got a six-piece band-guitar, bass, drums, and three horns. We’re competing in the International Blues Competition in November (2007). If we win here, we go to Memphis. If we win there, it’s instant national recognition.”

As for Craig Tarwater, after the Daily Flash split up he played with the aforementioned Eddie James and the Pacific Ocean. He then formed a “would-be supergroup” along with Don MacAllister of the Daily Flash, ex-Iron Butterfly singer Darryl De Loach, ex-Easy Chair/future Mothers guitarist Jeff Simmons and ex-Dynamics drummer Ron Woods, called Two Guitars, Piano, Drums, and Darryl. In 1969 he was part of the band that made Jeff Simmons’ Lucille Has Messed My Mind Up album (see separate article this issue). He later played with Etta James, Barry White, and many others, including Arthur Lee (he appears on the Vindicator album).

Today I live in Touchet, Washington, with my three Lhasa Apso girls,” says Tarwater, ” and work full time as an interior-exterior painter. I still play the guitar. I do not gig any more, but am still hireable.” He also teaches guitar and offers an instructional video course at www.craigtarwater.com

CHAPTER 10: Living In The Hot Zone

Randy Holden emerged from his self-imposed exile and began to make music again in the early ‘90s, beginning with the Guitar God album, released by Captain Trip Records in 1994. He has continued to write and record music, and also paints.

As for his days with the Sons of Adam: “I have mixed feelings,” says Randy. “There is an emotional feeling of total passion that becomes overwhelming when you’re playing in the ‘hot zone.'” He goes on to explain in detail the sound the amplifier gets moments before either the speakers ‘fry’, or the tubes ‘fry’. In the case of a Marshall amp, the tubes get so hot that they burn out at peak volume, but you have a few minutes before this happens, when the amp maintains the perfect tone of distortion. Randy calls this the ‘hot zone.’

“That’s what I liked. If we couldn’t be there, it didn’t interest me. You can get up there and strum a guitar, and do whatever, but to get up there and make that thing sing, cook and cry, that’s where it’s always meant something to me.”

“The Sons of Adam were a fun band,” he concludes. “Actually, the band was really heavy onstage, live. They were really a good band, but things just never came together for the band to survive.”