-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

The Monks – Monk Time

This article was the cover story of Issue #11 of UGLY THINGS in the spring of 1992. At this point in time, only two of the original Monks had been located. In the years that followed there would be a book (Eddie Shaw’s Black Monk Time), reunion concerts, an award-winning documentary (Transatlantic Feedback, directed by Dietmar Post and Lucia Palacios), tribute albums, and numerous reissues. But UGLY THINGS got there first.

I’d like to dedicate this article to the memories of Dave Day Havlicek and Roger Johnston.

MONKS STORY by Mike Stax / INTERVIEWS by Keith Patterson and Mike Stax

The music of the Monks is the stuff of true greatness: huge chunks of reverberating bass and drum rhythms, beaten into further frenzied overdrive by the atonal gash of an electrified banjo; this overlaid with the rapid-fire piercing squeals of delirious organ wailings and the hum and howl of fuzz and feedback as some maniac jaggedly assaults an electric guitar; this all pushing forward the angst-driven, aggressive voices shouting: “I hate you baby with a passion…” “People go to their deaths for you…” “Boys are boys and girls are joys…” “Pussy galore is coming down and we like it… we don’t like the atomic bomb…” “Shut up! Don’t cry!” and “Higgle-Dy Piggle-Dy—let’s do it!”

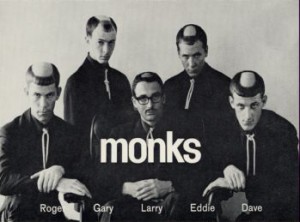

The Monks may be the strangest group ever to take form. Five American ex-servicemen stationed in Germany in the sixties, all dressed in black with heads shaved like monks. This was radical stuff for Germany 1965-66. Coupled with their violent, near-insane music it’s beyond radical for ’66, ’76 or even ’96. I could rattle on about pre-punk this and groundbreaking minimalist that, but that would be too pat. What the Monks were doing back then was way beyond that. The world still hasn’t caught up with the Monks.

I’ve seen a few small articles on the Monks in the fanzine press over the years, but no one had ever managed to track down the band and get their story firsthand. I was thrilled then when my good friend Keith Patterson located not one but two of the Monks: singer/guitarist Gary Burger and bass player Eddie Shaw.

Keith and I both visited and interviewed Eddie, and a week or two later Keith also interviewed Gary. The results of those in-depth conversations follows.

********

It was with some trepidation that Keith Patterson and I walked up to the front door of Eddie Shaw’s house, after having made the long pilgrimage north to Carson City, Nevada. We were about to meet face to face with a Monk, in fact, the man who “dreamed hell’s bass part.” What lay in wait for us we could only guess. Given the Monks’ weird image, their bizarre and uncompromising music and their G.I. background, just about any scenario seemed possible.

Ed turned out to be a relatively normal and sane individual—considering he’d been to hell (and Hamburg) and back with the Monks. He began by giving us a tour of his hometown. Carson City is a town in a state of mild schizophrenia. Part of it clings to a historical Old West tradition of goldmining and gunfighters; another part strives to offer the bright lights, glitz and high-rollin’ casinos of its distant neighbour, Las Vegas.

We stopped in at the Nugget, the casino where Ed played trumpet with his first band, a teenage jazz group called E Cuarto Unem (“cos we were all intellectuals”or at least we thought we were”). At the same time that young Ed Shaw was aspiring to be a juvenile Miles Davis, in another room at the Nugget a 14-year old Wayne Newton was onstage with his brother, doing basically the same act that earns him millions today in Las Vegas. Ed Shaw went on to less profitable ventures, but he’s seen and done things that Wayne Newton has never even dreamed of.

Next, as storm clouds gathered ominously on the horizon, we headed out of town in Ed’s ’48 Army Jeep. Ed figured we might want to see Carson City from a higher elevation so he proceeded to drive the Jeep up the side of the nearest and biggest mountain. As the town dropped away below us, the narrow road became a rocky footpath, then it just became rocks. We shook, rattled and rolled our way to the top, admired the view, then headed down the other side.

Next stop in the middle of this rocky wilderness was an abandoned mill from the mining industry. Nowadays this stony skeleton is only visited by teenage potheads, would-be ‘Satan’ worshippers, and the curious few, like ourselves. Except for the colorful proliferation of LSD, Lucifer and heavy metal inspired graffiti, the place looks more like an abandoned cathedral than anything else; not an inappropriate haunt for a Monk.

It was here that the gold was extracted from the ore, with the use of cyanide. Rusted, empty barrels of the poison litter the ground in their hundreds, the noxious odor permeated the air, adding to the tangible mood of evil and foreboding.

After another short, bumpy drive, we found a real road again and soon arrived in Virginia City. The town still looks like the Old West, with old time saloons, stores and hitching posts; much like Bonanza, which was filmed in these parts while Ed Shaw was far away in Germany playing rock’n’roll with the Torquays and the Monks.

The dark clouds were now rolling in faster and it was time to head back to Carson—this time around the mountain rather than over it. After a few beers at Ed’s local watering hole, we stopped at the supermarket to pick up some necessary supplies for the evening: TV dinners, potato chips, cheese dip, lots of beer. We were now ready to begin the interview and learn the full, incredible story of the Monks.

(I would also like it officially entered into the record that Keith and I wore original Monk ropes around our necks for the entire duration of the interview.)

A week or so later, Keith visited Gary Burger’s home in the woods of Northern Minnesota to get his side of the saga. What we present here is a combination of their two reminiscences with minimal interruptions from Keith and myself….

Eddie Shaw: I joined the Army right at the beginning of ’61. I was going to get drafted; I was number three on the draft list. I joined so I could get in the army .band. I took the test for the army band and passed it. They said, “OK, you’re gonna spend the next couple of years down in Fort Ord by San Francisco.” I said, “To hell with that!” ‘Cause if I was going to be in the army and be miserable I wanted to see some other part of the world.

So I told them, I didn’t wanna be a musician, just put me in anything, I wanna see some other part of the world. So they sent me to Germany. I was a forward observer and surveyor in B Battery of the 6th Artillery.

One of my jobs was to drive around this drunken sergeant. He promoted me very quickly to sergeant myself. Then I met Gary Burger and the Torquays. They were just a hot band on post.

Gary Burger: I went into the military in ’61. I didn’t like the army very well. I went to Germany in ’62. I was in an artillery outfit stationed outside of Frankfurt in a little town called Gelnhausen, where I met Dave and Larry and Ed and Roger. We were all stationed on that base.

Keith Patterson: How did the Torquays come together? You were originally a duo, right?

GB: Dave and I were basically the nucleus of the Torquays. We started playing—just the two of us—in little German guest houses near the base. They’d pass the plate at the end of the night and we’d take our pfennigs home and count ’em in the latrine.

After playing awhile with two, you start thinking maybe three’d be better, then maybe four’d be better. And of course it ended up being five.

At the time Eddie Shaw approached the group to audition, they were a 4-piece, with Gary Burger and Dave Day on guitars and vocals, Larry Clark on organ, and a German civilian called Hans on drums. Ed was bored with military life and was looking for a means to vent his frustrations, “Anything to make myself feel like a human being again.” There were no jazz groups on base for him to play trumpet with (his first instrument), but there were several rock’n’roll groups, the best and most popular being the Torquays.

Hearing that the group needed a bass player, Ed bought a bass guitar, learned the basic rock’n’roll chord changes and went to try out at a Torquays rehearsal in the auditorium of the service club.

Eddie Shaw: I started playing with them, after they’d finally decided they’d take me. Now we were in business. There were a number of guys who hung around the service club who wanted to be the vocalist. Zack (Ernie Zachariah), a tall, dark Italian was hired because he knew the most songs, and he could sing “Ruby” just like the original. We did a lot of Dion & the Belmonts, and guitar instrumentals like “Pipeline.” We did a little bit of everything.

The Torquays’ repertoire also included their theme song, “Torquay” by the Fireballs, plus lots of Elvis (Dave knew every Elvis Presley song there was,” remarks Eddie), some Chuck Berry and Ray Charles, and Larry’s specialty, “Green Onions.”

GB: We soon learned that we could get time off from the army if we played our cards right, which we did very well. The last year or so, all we did basically was play music. I got out of the Army in August 1964.

ES: The last year I was in the army, I was in the special services, which was something called “Operation Jingle Bells.” We played goodwill shows for the American soldiers and German civilians.

Charles Reich, who was the biggest agent in Frankfurt, said we could make a good living in Germany if we stayed there; so we did. We started playing the clubs around Stuttgart and Munich, and bars close to the army bases where the American soldiers would hang out. We played what we wanted to play and had a good time.

By late ’64, Zack was long gone and Roger Johnston had joined the band on drums. The set list now included some Beatles and Stones material, and lots of Kinks. There were also new songs written by Gary and Dave, such as “Paradox,” “Jump Out the Window” and “Love Came Tumblin’ Down.”

In early 1965, the Torquays recorded a single in Heidelberg: “Boys Are Boys” and “There She Walks,” both original songs with a strong R&B flavor and a twist of raw weirdness that hinted of stranger and better things to come. “Boys Are Boys” would later appear in a more radical form on the Black Monk Time album. Only 500 (or perhaps 1,000, no one can confirm) were pressed and the band sold them when they played.

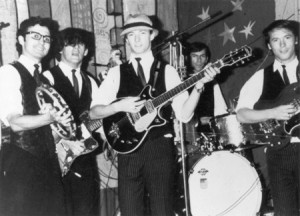

The Torquays, ca. early 1965. L to R: Larry Clark, Dave Day, Gary Burger, Roger Johnston, Eddie Shaw.

GB: We were interested in original music right from the start. That record was basically a statement that, “Hey, we’re gonna record. Here’s two original songs, with—whatever—a hundred more in the wings.” It just happened that those two songs were ones we had ready, and they were our exclamation point that “we’re ready to do it now.”

In truth, we weren’t ready to do it. We needed another year to get ready. It was probably nearly a year later when the Monk tunes started to come down.

ES: We had a lot of original songs. We were one of the few bands who were working who had original stuff. The Germans weren’t doing it. We thought, if you were doing covers of stuff, you might as well do your own stuff too.

We were working seven nights a week, going from town to town, or playing month long engagements at different places. Sooner or later, something began to dawn on everyone.

In Germany it was: here’s a club next door and a club next door and a club next door, and people go from door to door, looking to see who’s doing what. And you’ve got the doormen out there trying to pull people in. Beat music in Germany was like a new phenomenon. There was an insatiable hunger for it. Anyone who could play three chords could get himself a job, if he was under 25 years old. The environment was one that, if you were there, you were just swept into it. But after you stand and look at all the groups around you, you realize that everyone’s playing the same material. Maybe one does it a little better than the other, but it was all the same. At that point, you started saying, “Well, wait a minute…”

GB: The Beatles were big time. They were doing the sweet stuff: “P.S. I Love You,” “Eight Days A Week”… Our impression of the Beatles was that they were “sweet sweet.” They did some damn good rock’n’roll, hut generally speaking they were these pretty harmonies and these sphincter-tight band arrangements. We thought that there’s gotta be another way to do this.

KP: The Monks sound seems totally unprecedented to my ears. How did you stumble across the idea?

GB: I guess I would have to say we dreamed the music. Maybe that sounds ethereal and nonsense, but I guess that’s how it happened. We basically came together one day and said, “We’re tired of playing all this sweet garbage that talks about how pretty you are and how sweet the world is.” The world wasn’t a sweet place. Germany itself was a troubled country.

That’s where we were living, and we got a lot of our influence there.

I think the music came from our dreams. We’d finish the gig at three in the morning, playing seven hour nights as Torquays, seven days a week, and go home afterwards or go party somewhere. What would we talk about? We’d talk about our music. What would we dream about when we’d go to bed? We’d dream about the music.

The Torquays hooked up with a team of managers (Wolfgang Gluzczeswki, Carl Remy, Walter Niemann, Gunther and Kiki Neumann) and the concept of the Monks’ music and image evolved over a period of many months as the band continued to play around Germany.

GB: We got some outside help, but I think basically the Monks was a creation of the Monks and of the Torquays and our heads in there. The idea was simplicity, repetitiveness, simple lyric lines, and don’t make the song too long.

ES: We sat down and we took all our songs and we all worked together. Gary and Dave had some basic songs; they’d written all of them up to that point. Then everyone got in and we j said, “OK, what do we don’t like?”

We broke the songs down. Like, “Boys are boys, girls are joys, da-da-da-da…” There’s four verses. You start taking words out. OK, “Boys are boys, girls are joys”—we’re not saying anything more than that so we just leave the rest of the words out.

GB: Editing is the key to anything, whether you’re writing music or being as direct as possible. Music to us at that time was no exception. We were in a country where minimalism with a lyric was important to us from the point of view that “let’s make everybody understand what we’re saying.” If we had too many lyrics, we’d lose that understanding and the ability to bridge some of those language barriers. So the minimal lyric feeling is a direct result of us playing rock’n’roll in Germany.

ES: We started playing with tension. Actually, that was the basis of our writing. You could find the tension point in an audience; you could watch them getting nervous. We had very astute managers who gave us advice. One thing was: just don’t let the audience fall asleep. So after awhile we’d just watch. If they were talking to each other, if they’re out there having a “dating game,” and they’re not watching the band, well, then the band’s not doing its job. Then you should be working for $20 a week or putting quarters in the jukebox—’cause that’s all you’re doing. So we became very aggressive and demanded attention, somewhat like a small child. And when people got mad, the idea was to just laugh at it.

Mike Stax: Did you throw out all the cover material as you made the transition from Torquays to Monks?

ES: We’d still do it. Even as Monks we still did it sometimes, if we had to. But the thing was to change the sound and not sound like everyone else. To do that we had to look at different instruments, or a different way of playing them. We wanted rhythm. A banjo is not a melodic instrument. It felt like it had more rhythm, so we looked for one.

If you’re looking for a new sound, then you start looking at different instruments, and then you start trying them out. It’s not just a matter of saying, “Wow, this one sounds best.” ‘Cause sometimes what sounds “best” can get old very fast. Sometimes what just sounds raunchy… “This sounds dirty; this sounds horrible!” You’ve gotta love it, y’know? (laughs) That’s how the banjo came about. We didn’t know how to amplify it, so we put two microphones in it.

MS: And what kind of amp did Dave play it through?

ES: I think he had a Vox, an AC30 or something.

GB: Nobody knew how to play a banjo, but then we decided a 6-string banjo would be the answer, ’cause you can play it like a guitar. You pick it up and bingo! Dump the rhythm guitar and use a banjo.

What can you do about drums to make them more primitive sounding? The idea there was to kick out the cymbals. The early people of Africa and Mesopotamia or wherever that had drums, they had big gong cymbals or something, but they didn’t have drum sets with cymbals. So let’s get rid of the cymbals. Instead of using a cymbal, use a tom-tom, my friend. And Roger did.

You combine tom-tom and banjo with a kickass bass—”the bass of hell”—with feedback guitars and organ and yelling, screaming voices, then you might have something and people might wake up and listen to you.

ES: The idea of it was to get as much “beat” out of it as we could. As much “bam-bam-bam-bam” on the beat or whatever. The only time cymbals would be used would be for accent. If anyone wasn’t contributing towards rhythm, then it wasn’t part of the Monks sound. We took every instrument and tried to make it a rhythmic instrument. At that point, Larry, with the organ, became the melody carrier when it came to the solos and stuff. His thing was not to play it pretty, but to just go up and down the keyboard; sarcastic and brutal. The idea was to keep the energy high.

So, in summation of what that theory was, it was rhythm and energy. High energy and high rhythm. If one is confined to a cell and has to listen to it for six months, he’s gonna go stark raving mad, because it’s gonna drive him crazy. Even now, when I listen to it, it makes me nervous. It’s like my worst nightmare. If you do that every night for two years, it’s overdrive. You’re in overdrive all the time. It’s aggressive. If you listen to one song after another, it just attacks you.

KP: It’s angst.

ES: It’s angst. That’s exactly what it is.

MS: Post-army angst.

ES: Some people say that the Monks’ music is pre-punk…

MS: No, no. Punk is just post-Monk! (laughter)

KP: How did you hit on the feedback? Were you motivated by bands like the Who?

GB: Sure, we were motivated some by the Who, the Pretty Things and so on. The Pretty Things were a great band! They were high on our list of people we listened to. But one incident that stands out is I laid my guitar up against my amplifier one day and forgot to turn the volume off. It didn’t make any noise for a second. It gave me chance to get three steps away and it started going around. Eddie was standing up there, he still had his bass on, and he started going bombababombababababombababom. That kind of turned my head. And Roger was on drums… I know it sounds crazy, but that’s exactly how it happened at a rehearsal. Pretty soon we were just doing it. I got the guitar back up, I cranked up the amp and the guitar and we had a great time for a half hour until I blew a speaker out. So that taught us that we had to buy bigger speakers.

KP: What kind of amp were you using?

GB: I probably had a Bandmaster Fender. I eventually got a Super Beatle (cabinet), but I had a special amplifier. I just used the speaker on that, I had a real high-power amp driving it. That particular amp had been modified so many times, I don’t know what it had in it! (laughs) I’d bought it from a German guy who made amps over there. It really had a crystal clear, super high-end tone to it. It was good for some things and bad for other things, but one thing it would really do would be it would feedback.

Fuzztones were also a big part of our deal, which would help with the sound. We bought a case of those Gibson fuzz-tones out of the StatES: it was like twelve fuzztones. I burnt them all up over a couple of years.

I also used a foot pedal a lot; a volume-tone foot pedal. It was a Fender, I believe. It was the kind that went sideways, up and down. I used that on “I Hate You” and “Love Came Tumbling Down” on the album.

The new, individual sound was gradually invented. Now the band needed a simple, memorable name and image. Something hard and strong that communicated its message instantly. After suggestions along the lines of Fried Potatoes, Molten Lead and Heavy Shoes were all (fortnately) rejected, someone suggested the Monks. After some initial misgivings—Larry’s father was a priest, after all—they decided they all liked it. They would become Monks, with all black clothes, a rope around the neck, and the tops of their heads shaved bald. It was a radical transformation—especially for 1965.

ES: It was a case of going through the whole process of image, sound and presentation, and finding something that someone could see and understand without having to think about it. And if we created some primeval urge to break laws or to defy morality, then that happened to be that person’s problem. It wasn’t our problem.

MS: What about the shaved head part? Was that a difficult step?

ES: We decided we were going to do it as just a dime size. We were going, to cut our hair real short and then shave a little circle back there. I don’t know what it was, Roger was not happy at first about being a Monk, but he was the one who said, “The hell with it.” We went into this place and they took pictures of us and he just sat down and said, “Cut the whole damn thing off up there!” (laughs)

So we looked at each other and said, “Oh god, there goes our future. Now we’re not really gonna be attractive at all!” (laughter)

But the thing was, with the all black clothing your faces stand out. If you wear white clothing, you don’t see the face, you see the clothing. If you wear black, the thing you see is hands and face. So with a combination of all black and the head shaved… and we got so radical that we made sure that our fingernails were clean and our shoes were shined. This was like being neurotic, psychotic—full of neuroses, you know. When you walk among people you don’t look like you’re real anymore. People would always say, “You don’t look real. You look like you’re made out of wax or some artificial material.”

MS: What was the significance of the rope around the neck? Someone once described it as a hangman’s noose.

ES: The idea was that people were wearing ties and so forth. The managers said, “You’ve got to have a tie.” That was the most logical thing, because what do friars wear around their necks? In some ways it conjured images of walking on the wall. There’s nothing safe in the imagery of that. It’s not something that’s comfortable.

MS: Did you ever feel like you were being molded into your image by your managers?

ES: It would depend on the person you talk to. Sometimes Gary would say, “I think we’re being used.” But that happens no matter what you’re wearing or what you’re doing; after awhile you start saying, “Someone’s using me.” But in the end, you’re doing it yourself; no one’s demanding you do that.

MS: How did the audience reaction change when you became Monks?

ES: In Heidelburg, the Torquays were their favorite band. All of a sudden it was the Monks, it wasn’t the Torquays for the next gig. They said, “What the hell’s going on with you guys? We liked you like you were!” So we played Monks and, man, that was brutal. All of a sudden everybody hated us. Everybody that knew the Torquays hated the Monks—they wanted “Skinny Minnie!” (laughs)

I remember that the Torquays, as a band, were always fun. Everybody was happy, everybody was laughing, everybody was having a good time. The Monks was different. I remember people not looking at the band. They were looking down; they wouldn’t look at the band! (laughs) They were afraid of us.

For the first time, we weren’t able to walk among them and have everybody slap you on the back and everything. You’d walk through and everybody would stand back. No-one talks to you. That’s a hard thing to get used to, ’cause your first reaction is, “Something is wrong with me.” It’s just that it is an authoritarian image.

GB: Either they hated us or loved us. We had more hate than we had love, it was hard .for us to keep it going because we could feel this animosity from our audience. I had a guy jump onstage and grab me by the throat in Southern Germany, he hated us so bad. A guitar neck, where the tuning knobs are, in the side of his face calmed him down.

We had to live with this image that we’d created, and we had to be dedicated to it. We knew that image would offend some people, and I think that image may have offended us more often than it offended any of our audiences. They didn’t go home with it; we did. We didn’t mind. We knew what we were doing and we were pleased to be doing it, but there’s a lot of memories in there which I haven’t totally sorted out yet.

Before being signed, the Monks went into the studio and recorded an album’s worth of material. The tape included many songs which later appeared in different versions on their Polydor album, as well as other material such as “Uschi Pushi” and “Pretty Suzanne.”

KP: How do the earlier Monk recordings differ from Black Monk Time?

GB: They’re different. They’re more pure in their concepts. It was done in Ludwigschaffen, six or eight months before Polydor picked up on us. Each song started off with a real short organ signature, followed by a little hint of what the song might contain, followed by the song—which was often rather long and tedious.

ES: We were still experimenting. We went in there and recorded it and we didn’t like how it was. Gary was having problems with the solos and so forth, so we had to go back and rethink it.

With the completed tape in hand, the Monks and their management approached Polydor for a record deal.

ES: The management gave a full professional presentation. One of the things our managers did during the whole time we were working on transforming ourselves, they were there with cameras photographing. They were experimenting on their own as to how they could visually present us. So while we were presenting our stage act, they were experimenting with ideas of how to promote us. In that sense, it really was more than five people. It was a whole organization.

They would do photographs and say things like, “Eddie, when you make this sort of gesture, it doesn’t look good.” That’s people studying themselves, to see what they look like to the audience. You’re constantly trying to figure out how you’re going to entertain these people or how you’re going to give them something that they’re looking for. And they’re looking for something or else they wouldn’t be there.

The Monks’ official photographer was Charles Wilp, who later became the official photographer to none other than Ronald Reagan when he was president. Polydor were impressed—or at least intrigued—by the presentation, but the tape was deemed unsuitable for release.

GB: I think Polydor decided that it was a little too much. Punk music—or the Monk music—in ’65 was a little radical for Polydor. I think they picked up on it just because there’s an attraction and also an aversion to radicalism, whether it’s in music or whatever you might be looking at. If it’s radical, you’re both attracted and repelled by it, and I think that was Polydor’s attitude when they picked us up: “This stinks. But let’s try it!” (laughs)

Jimmy Bowien (who became the Monks’ producer) was a real smart guy. I think he saw something there that maybe some of these companies didn’t see. He was willing to gamble. He put his reputation on the line somewhat for the investment Deutsch-Gramophon had to put into the production of the Monks. I personally believe that over the short run his judgment was probably not vindicated. But over the long run, maybe his judgment was more than vindicated.

With Jimmy Bowien at the controls, the Monks went into the studio in Cologne to record what was to become Black Monk Time. Sessions took place late at night and into the early hours of the morning after the group was done with their regular live gigs.

ES: We were working at Storyville in Cologne, and we’d get done at 3 o’clock in the morning, and then we’d record until 7 or 8 in the morning. I think it took a week to record it; five or six days.

GB: For me, the sessions were drunks. That voice on those records was done by drinking whiskey—raw—and getting a raw sound; burning the throat and blowing it out right up front. So before you even started, the voice was gone. Straight, raw whiskey does that. That was our producer’s idea. I guess he was right. We had a great time in the studio. I don’t think we were drunk—let’s back off that a little bit—but there was a gentle buzz on from alcoholic beverages. I don’t think you’d better print this, Mike, ’cause let’s keep America and the world a little purer than we really are. (Oops – MS)

MS: You recorded the album on 4-track. How much overdubbing was there?

ES: None. Just the vocals went on later. We had problems with it. The way we were playing, it was very difficult for them to record, because at that time the best recording technique was to play very quietly so that you got separation on the mikes. But if we played quiet we couldn’t get that Monks sound, so we said, “You’re gonna record it loud or record it not at all.” So they would wrestle with it. So really the Monks was an experiment from the day it started to the day it ended. It was an experiment for everybody: the managers, the record company, and for us.

MS: How did you get over your problems in the studio in the end?

ES: Well, it was a big room and one time they tried to have us all in different corners of the room. But then we couldn’t get it together because we couldn’t get our signals together. So we moved everything back in closer. So then all the meters are in the red and it’s like white noise. So there were many hours of us standing around while the engineer and Bowien decided, “How can we do this? How can we get this feedback? How can we get in there without driving everything crazy and just having one big blob of sound?” But in the end they did it. It took ’em awhile.

The album opens with “Monk Time,” an introduction to the Monks and a harsh statement of intent and beliefs, with a sense of humour seeping through the cracks…

Alright, my name’s Gary. Let’s go.

It’s Beat time, it’s Hop time, it’s Monk time.

You know, we don’t like the army.

What army? Who cares what army!

Why do you kill all those kids over there in Vietnam?

Mad Viet Cong!

My brother died in Vietnam.

James Bond, who’s he? (musical explosion…)

Stop it, stop it, I don’t like it!

It’s too loud for my ears.

Pussy galore is coming down and we like it.

We don’t like the atomic bomb…(musical explosion…)

Stop it, stop it! I don’t like it! Stop it!

What’s your meaning, Larry? (organ noise)

Ah, you think like I think.

You’re a Monk, I’m a Monk, we’re all Monks…

Dave, Larry, Eddie, Roger, everybody, let’s go…

It’s Beat time, it’s Hop time

It’s MONK TIME NOW!

GB: “Monk Time” was an anti-war song of the hardest, most brutal kind. We were just out of the army, but that had nothing to do with it. Even when I was in the army with Ed, Dave, Larry and Roger, do you think we wanted to go shoot people? Not a chance. And we didn’t want people shooting at us, and we didn’t want people shooting at our buddies. Vietnam was a real strange affair around then. Kennedy had gotten killed, Johnson was putting troops in, and the whole thing was escalating. Our friends were being sent there.

The lyric, “My brother died in Vietnam”—not my literal brother, but my human brother, whether he was a white man or an Oriental; it wasn’t meant for either one.

ES: “Monk Time” was supposed to be our theme. It was like Howdy Doody who hated everybody. Gary just had the perfect voice for it.

We’d worked on the arrangement together. At the time, we’d never done this before and it made me nervous. It was just something different. Here you’d have the drums playing and the organ playing, but no bass—you’d wait awhile and then you’d come in. With five instruments you can maximize your options by sometimes laying out: just drums and bass, or organ and drums, or banjo and drums.

MS: You had a problem with the line, “Why do you kill all those kids over there in Vietnam.” Why?

ES: I felt very uncomfortable, and the only thing that would make me feel comfortable—nd everyone had to be satisfied—the only thing that made me accept it was when we added “Mad Viet Cong.” At the time, everybody was knocking down the Vietnam War. And I was against the Vietnam War. I didn’t think it was right, and I was living in Europe and everyone was telling me it was wrong, and I knew it was wrong…

MS: But you didn’t want to put down the guys who were being sent over there, right?

ES: That’s exactly right, because we came from the same school: the United States Army. When you go in the army you get indoctrinated to perform: to kill, whether you believe in it or not, without thinking. When you get out of it, you get to think again, but it takes a long time. It affects men’s lives who’ve been in the army and who’ve spent their years right out of school with no other post-secondary education. They learned that camaraderie and that thing like, “I can run twenty miles if someone’s gonna make me do it” and all that stuff. So you feel a little bit of loyalty to those people, whether you agree with the war or not. We disagreed with the war. We made that perfectly clear. But the hard part was to say that we were blaming the guys who were doing the shooting.

MS: To me, the line is asking the US government: why are you sending all those kids over there to their deaths?

ES: Yeah. But you know what? Governments don’t listen to rock’n’roll, but the guys in the army are listening to it. In fact we had some trouble with that song in Mannheim or some place. There were some soldiers there, and one was sitting there and he started crying. He’d just come back from Vietnam. ‘Cause everybody was hitting on the soldiers— spitting on them all this. They weren’t the problem. It was the government that was the problem. It was all those assholes up there who were running things.

KP: Tell us about the song.”Shut Up.”

GB: The song “Shut Up” is basically a statement on the condition of the world as it’s always been and as it probably always will be. “Shut up, don’t cry… world is so worried,” it’s always worrying, there’s always crisis.

KP: What about “Boys Are Boys”?

GB: Fluff; but a hell of a rhythm.

KP: Hell of a bass sound! Monstrous!

GB: That’s Ed’s best bass sound on that one. I wish they’d mixed more of the songs with the bass that prominent. It really is a good sound, but the lyrics could be a Beatles song. I’m a little ashamed of that song.

KP: “Higgle-Dy Piggle-Dy”?

GB: That grew out of a song called “Jump Out the Window.” We used the rhythm from that earlier song as the basis for that. And “Higgle-Dy Piggle-Dy” just means, I think: CHAOS.

It’s one of my favorites.

“I Hate You” is my favorite. “I hate you…but call me”—there’s something very poignant about that, because there’s a love affair involved in that. I think most males or females can relate to that. There’s a lot of love/hate relationships that do damn fine. They tend to look ugly from an outside perspective. But you watch ’em and they’ll go on for years, and they’ll die and get buried side by side. You’ve got to have that polarity.

KP: Is that song about a particular person?

GB: No one in particular. One time I’d be singing that song and I’d be singing it to some girl out there at the time. Another time I’d be singing it to a government that was out there. Any person really. You can take it any way you want. I think that’s one of the things the Monks had, was that the lyrics were pretty general. You could interpret them in a way that suited you. I think in your life—and anybody in their life—needs a song like “I Hate You” from time to time; just to help ease the pain.

ES: When we did that song, people would say, “Wait a minute; that’s being too overt.” We did get some criticism from the record company, “Can’t you just say that in a different way?”

“No, no. That’s just the way it’s got to be said.”

MS: What was the idea behind “Complication”?

ES: That really has a little German in it. When you’re living in a different society you pick up part of the culture. I was actually at the point where I was sleeping and dreaming and thinking in German. ‘Cause I was speaking German all the time. I was only speaking English when I was with the group. When you’re doing “Complication,” you’ve got your American background and they’re in this turmoil. We’re sitting in the Top Ten Club, reading the newspaper, seeing that Watts is burning down, they’re counting bodies in Vietnam and the war’s playing every day on TV. We only see it like we don’t belong to it. We’d actually become divorced even to our G.I. background at that point. That’s just your reaction ’cause you’re a Monk and you’re living in a country that just lost the last war. You’re talking to men who themselves were losers, who supported Hitler and all that stuff. You’re reacting to everything around you. “Complication” was the reaction of someone who was living between cultures.

KP: The way you sing lines like, “People go to their deaths for you…” You say it like you mean it!

GB: We did mean it. They weren’t just words, they were words that we meant—on that song anyway.

KP: Was “Drunken Maria” about a real person?

GB: Oh yeah. We knew several Maria’s and they were all drunks! (laughs) That’s true! So we decided we needed a song that commemorated all these Maria’s. They were all Yugoslavians, every one of ’em! (laughs) They were all dark haired, brown-eyed beauties, and I miss ’em all.

KP: Were there any influences at work when you were trying to do a close harmony number on “Love Came Tumblin’ Down”?

GB: I think we were trying to, but we weren’t able to do it well. I’ve never been happy with that song. I felt it was a little flat in one spot, a little sharp in another. That was written earlier and it was kind of renovated into a Monks song. We changed it, and basic-ed out the rhythm and the changes, and just turned it into a Monks song. But it’s still a love song. It’s a Monk love song, if you wanna call it that.

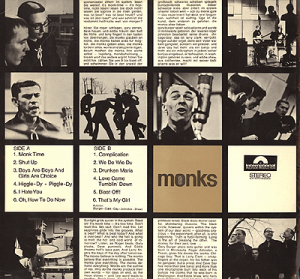

The completed album, titled Black Monk Time, was a crashing, smashing, thunderous explosion of musical noise and bizarre themes. It was released onto an unsuspecting world in 1966, along with the Monks first single, “Complication” b/w “Oh How To Do Now” (two tracks from the album).

Now the Monks embarked on an even more rigorous touring schedule. A punishing regime of mostly one night stands that would last for the next year and a half.

GB: Touring was like a big blur in my memory. We played a couple of years non-stop, with no days off. They were nearly all one-nighters. I think we’d end up with maybe Christmas off. The whole thing was at that pace. I weighed 120lbs when I came back from Europe, if that’s any indication of how the touring went. It was just a non-stop grind. It was tiring and demanding. Nobody should play that much.

I can remember driving down the autobahn one time. We had a bus that carried all the equipment, and one of us would drive that, and we’d have a car or two along and we’d follow the bus. I noticed this bus weaving a little bit. Dave was driving it that day. There’s traffic going by at 100mph—there’s no speed limit—they’re going-around us and past this bus. We pulled up beside Dave to see what was going on and he’s sound asleep at the wheel, going down the freeway at 80mph. His eyes would kind of part a little bit every now, and then—just to make sure he was still on the road—and then he’d close them again. That’s a pretty good way of describing that two years for all of us.

MS: What were the venues like in the small towns?

ES: They were beer taverns, like old-fashioned dance halls. You could do three of them in a day. You’d just go from town to town to town to town, jumping up and playing two sets and off to the next one.

MS: When you went to those small towns, what did people make of you? I think of Germany in 1966—that’s only twenty-one years since Hitler!

ES: We got attacked a couple of times. They would jump up onstage and try to hit us—try and kill you.

MS: What kind of people were these?

ES: They were young, working class men, sort of pretending their religion had been smeared, or maybe we were Americans taking advantage of their disadvantage, whatever. We’d also find that with some German bands. The local band opening the show, some of them would actually hate us. And we were the only band who’d let everybody use our amplifiers! (laughs)

MS: Do you think some of those kids saw the Monks as part of an American occupying force?

ES: We were up north most of the time. We weren’t around where most of the Americans were. I never thought there was any difference between us and the audience; I really felt like I was a German at that point. And Dave did too. Dave had gotten really bad, because he couldn’t speak German and he couldn’t speak English! (laughter) He just got in between both of them. I just thought of those people as the same as I was—or I was the same as them.

MS: You played in Berlin, right? What was that like?

ES: Berlin was pretty sophisticated. Berlin was like playing for the college crowd, in comparison to, say, Southern Germany. In Berlin we would play clubs and people would just act like we were normal. In fact, I went to a party in Berlin one night and it was the first time I’d felt like I was being ignored. That hadn’t happened in awhile.

We’d travel through East Germany to go to Berlin. We’d stop some place and get out and kids would just gather around us and look at our clothing and look at our shoes. They would just literally stand next to you and it was like they were eating you with their eyes.

The funny thing about East Germans was that we were heroes when you’d read their letters. It was like, “You are the greatest thing that ever lived. You are my hope.” They’d hear us on Radio Luxembourg and see us on TV. It was different. The West Germans would say, “You’re fantastic. Would you please send me an autographed card. I’m your fan.” The East Germans would go, “I want to be like you. I want to come and see you some day.” There was something else in it, almost a note of desperation.

In between all the touring, the band squeezed out another single in 1966, recorded in “Hamburg: “Cuckoo” b/w “I Can’t Get Over You.” This record showed a noticeable softening of the Monks sound. Sure, the harsh fuzz guitar and booming bass and drums were still there (particularly on the B-side), but instead of the intense, confrontational minimalism of Mack Monk Time, “Cuckoo” in particular was downright wacky, to the point of being almost a novelty tune. Today, Gary dismisses it quickly with a few well-chosen words: “‘Cuckoo’ is a dog’s ass.”

ES: They said, “You gotta put something commercial on the next single.” There was always the pressure to be commercial; you’ll always have that pressure. “Cuckoo” was alright. We kinda had fun with it, because at the end of breaks some clubs would play it, and they’d open the curtain and we’d start playing with the record. Then they’d turn off the record and we would finish it.

GB: “I Can’t Get Over You” is a love song. Doggone it, the Monks are full of love songs! (laughs) It was one of the later songs we did, and I think that song was probably going in the right direction. It had a great rhythm. Boy, when it kicks off, it kicks off well. The song is a little bit too Iong. If I had to re-do it, it’d be a two minute song.

“Cuckoo” did quite well commercially and they did some television shows to promote it, including Beat Beat Beat. The Monks also made an appearance on Beat Club in Bremen (performing their amazing and never-released “Monk Chant”) and did another TV show at the German-American High School in Frankfurt with Manfred Mann in August 1966. (Manfred was particularly taken with their “Pretty Suzanne,” which he thought had hit potential.)

During this period, the Monks also toured Sweden’s folk parks and did a television show in Stockholm. Some people were under the misapprehension that the band were real monks, so one night they found themselves put up in a real monastery. The unholy Monks behaved as usual, getting drunk and rowdy and sneaking girls up the back stairs. The next day they were asked politely not to return.

Things began to cool down somewhat after the initial flush of “Cuckoo” publicity, and the band began to feel like they had over-exposed themselves on the German circuit. The Swedish tour was the first move towards breaking into other markets. 1967 found the band uncertain of their future and in disagreement about musical direction.

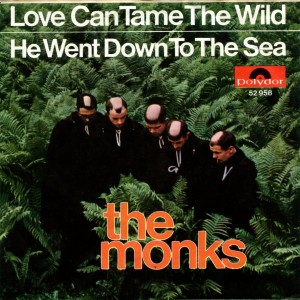

Their next single, “Love Can Tame the Wild” b/w “He Went Down To the Sea,” was to prove to be their last. The record showed a new Monks sound, a more melodic, pedestrian pop feel with mild hints of the emerging psychedelic movement, especially on “He Went Down to the Sea,” which featured extra instrumentation (including Ed Shaw on trumpet).

ES: We were a little more ambitious in the studio, to the point that really I don’t think the results were as good. We were arguing amongst ourselves. Some of us were purist and wanted to remain pure; others were saying, “No. We gotta change. You’ve got to join the rest of the human race.” It’s a normal “conform” pressure. They get you there because you’re different, then once they get you there they want you to become the same.

GB: The Monks were being pressured by certain areas—I may have been one of them—to soften up the sound some, as an experiment. There were more pressures than Gary Burger, but I was certainly one of them. I had a feeling that we could do some other things, more harmonies. My trend, probably, was to go the normal way, which was certainly wrong, in hindsight. “Love Can Tame the Wild” and “He Went Down to the Sea” was probably my statement in that direction. And, fittingly enough, that was the end of the Monks recording! (laughs) That record is a sign of a band wilting like a flower that’s seen its day.

The Monks lasted a few more months after the release of the last single, but they were racked with internal conflict and personality clashes. Nobody knew which direction the band should head. The writing was on the wall.

ES: The break-up happened accidentally, maybe four months after we did the single. We were becoming due for the second album. After the black one there was going to be a silver album and a gold one. People were getting dissatisfied with Polydor and we were wanting to go over to Philips; there was a hotshot producer there. What happened was that we started looking for other people to fix our problems. But we had to fix them ourselves.

With that last record, people like Carl Remy and Walter (Niemann, two of the managers) got really upset. They said, “What are you guys doing? You’re throwing it away.” They were pushing on us the other side saying, “Don’t compromise. There are no compromises.”

GB: There was a lot of conflict between two members of the Monks: Dave and Larry. Their conflict made it hard for the rest of us to maintain, because we’d be playing a song and they’d be throwing darts at each other. You’ve gotta work as a unit or forget about it. A band is essentially “one person,” and without that kind of unity you’re not a band.

ES: It was getting to where it wasn’t fun. It was manifesting itself in everybody in different ways. Dave was drinking too much. I was drinking too much. Roger was maybe taking pills too much—I couldn’t tell with Roger, other than all of a sudden he was sick a lot.

We really didn’t run around with each other much anymore. We all had our friends—different circles of people. I tended more towards jazz, ’cause that’s what I’d grown up with. I would go to places to see where Duke Ellington’s band was, ’cause they’d be living there and jamming in clubs and stuff. That’s where I’d go. Dave was always with his rock’n’roll buddies; all these Elvis Presley Monk freaks…

By the end, we were sick of each other; we were sick of the scene; we were sick of the pressure.

GB: We were supposed to do a tour. We were going to Saigon, Indonesia, Hong Kong and Tokyo. Then, after Tokyo, none of us really knew where we were going, but the assumption was that we were going to the west coast of the United States.

We’d just played a club in South Germany. Camera Club was the name of it. I think that was our last live gig. We had a month, or several weeks, before this tour was supposed to start and so we all kind of went to our own little hideouts for that month. While I was in mine, I got a postcard from Roger saying that he’d just about had it with this whole operation, couldn’t take it anymore, and suggested we get a hold of another drummer and continue on without him.

I made a phone call to our manager and told him the circumstances and he said, “Well, I’ll check it out.”

We did have a drummer, by the way, who would’ve plugged in real nice: Sooty from the Image. But our managers’ response, after considering all factors, was that the tour was off unless we had the five original Monks. Roger was already in Texas by then, so it was basically out of the question.

Roger had left due to internal conflict within the band. Anyone who’s been in a band for five or six years is gonna have internal conflict. He was just wore out. Physically depleted. So there ended the Monks, and so we let it go. I think for the most part we were happy to let it go by then.

With the band finished, the Monks went their separate ways. Like veterans returning home from some kind of war, each had to deal with the reality of what they’d experienced over the past few years, and reacclimatize to normal life.

MS: Was your experience with the Monks just a couple of years out of your life that you happened to be in Germany playing, or does it have some bigger significance to you?

ES: For me it was an educational experience. That was my college! (laughs) That was where I went to school. I often wondered later, how can I use this experience? When I came back here in ’68—off the tramp steamer I took a Greyhound bus back to Carson City—my family just goes, “What are you doing? What happened to your hair? Why do you look like that?”

I said, “I did that, I did this. Listen to this music I did!”

They looked at me and said, “Is that what you did over there?!”

“Yeah!”

“Oh. (pause) What are you gonna do tomorrow? Are you gonna go down to the Highway Department and get a job?”

So then I’d try and call up some of my old friends. “Bob! Listen to this!” Bob’s the fire chief.

He goes, “You know, Ed. I think you fucked up when you went to Germany.”

And I thought so too. I thought, Jeez, I did. I should’ve stayed here. What the hell did I do that for? (laughter)

GB: I’ve been divorced from the Monks for a long time, but, frankly, it’s a big part of my life—even today. I came away from them, I think, with some thinking that was a lot different, just by being a part of that. It wasn’t just a rock’n’roll band. The music was so basic, as much as we played I think it did something to our characters.

Once you’re a Monk, you’re always a Monk. Eddie and Gary (and Dave, Larry, and Roger, wherever they are) live with that reality every day of their lives. They have every reason to feel vindicated that as Monks they left a unique mark on rock’n’roll history that can never be erased. Long live the Monks. IT’S BEAT TIME, IT’S HOP TIME, IT’S MONK TIME!