-

Featured News

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1

By Harvey Kubernik

Singer, songwriter, actress and author Marianne Faithfull passed away on January 30, 2025.

In 2000 I discussed Faithfull with her first record producer Andrew Loog Oldham, the 1 -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and The Big Bopper Remembered 60 Years On

By Harvey Kubernik

February 3, 2019 is the 60th anniversary of tragic airplane crash that subsequently became known as “The Day the Music Died,” sadly referenced in Don McLean’s song, “American Pie.” Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. Richardson a.k.a. The Big Bopper died along with pilot Roger Peterson. After a February 2, 1959 “Winter Dance Party” show in Clear Lake, Iowa, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. Richardson took off from the Mason City airport, in a three-passenger airplane that Holly chartered piloted by Roger Peterson during inclement weather. It crashed into a cornfield in nearby Macon City, Iowa, just minutes after takeoff.

I will always remember the February 3, 1959 front page headline in The Los Angeles Evening Mirror-News, a daily newspaper who reported this accident.

Ritchie Valens’ death was a very big regional loss. He was from Pacoima, a suburb in Southern California. Ritchie’s records were very popular in Los Angeles and the surrounding communities. It was KFWB-AM deejay Gene Weed who first spun his music and the radio station held what seemed like an all-day shiva celebrating the life of Valens, whose record label, Del-Fi, was based in Hollywood.

I knew Buddy Holly from his appearances on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and from 1957 when he was on The Ed Sullivan Show. Holly’s records were also spun on KFWB. “Chantilly Lace” by the Big Bopper was a national hit.

Twenty-two years ago on February 3, 1997 I interviewed Keith Richards around a Rolling Stones concert in San Diego. We talked primarily about his just released Wingless Angels album. However, it wasn’t lost on each of us that 38 years earlier, Buddy Holly, one of his musical heroes, passed. An early hit record of the Rolling Stones was “Not Fade Away,” produced by Andrew Loog Oldham; the song was originally the B-side to Buddy Holly’s 1957 chart hit “Oh Boy!” In March 1958, 14-year old Mick Jagger saw his first rock concert in London at the Woolwich, Granada. “Not Fade Away” made a big impression.

Keith and I had a brief discussion how some music, like his Wingless Angels endeavour or the sounds of the Sun Records label, or any recording that penetrates, makes immediate impact and a connection on your soul, even decades after initial airplay or retail discovery.

“I think because it’s timeless music I call it ‘marrow music.’ Not even bone music. It strikes to the marrow. It’s like a faint echo . . . The body responds to it and I don’t know why…”

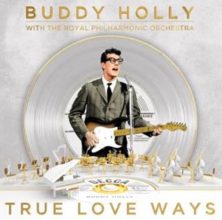

The Decca/UMe label this week releases Buddy Holly with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra: True Love Ways, a new collection of Buddy Holly’s most beloved hits set to brand new orchestrations. True Love Ways (the name of the song written for Buddy’s wife, Maria Elena) features Buddy Holly’s distinctive original vocals and guitar playing, set to exquisite arrangements newly recorded in England by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at London’s Angel Studios. The album is produced by Nick Patrick, the man behind successful orchestral albums for Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison, the Beach Boys, and the Carpenters.

Buddy Holly’s wife, Maria Elena Holly endorses the compilation. “Sixty years on, this wonderful album relights the flame, the songs and the music shines brightly again. I am proud for Buddy, his legacy continues to influence and inspire. THE MUSIC LIVES ON.”

Larry Holley, Buddy’s brother also touts the title. “This is what Buddy would’ve wanted done.”

True Love Ways is the poignant realization of a dream Holly first explored just four months before his tragic death.

On October 21, 1958, Holly embarked on a musical adventure he would have continued, had he had the chance. He entered the Decca Studios in New York for a three-and-a-half-hour recording session with an 18-piece orchestra, fronted by Dick Jacobs, known for bringing strings to rock & roll. They recorded four tracks: “True Love Ways,” “Raining In My Heart,” “Moondreams,” and “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” all of which are soaked in strings, clearly demonstrating a new direction for Holly’s music.

Holly’s widow explains that her husband thought then that the rock & roll era had peaked: “Buddy felt orchestral music in a popular vein was where the future lay, so he wanted to write, record, explore and innovate that style. So what better combination than the Royal Philharmonic and Buddy’s music. It’s just beautiful.”

Maria Elena also recalls Buddy telling her he learned to play the violin as a child and later, he had fantasized about writing film scores.

A January 24, 2019 Decca/UMe media press release hails the product: “True Love Ways’ orchestral arrangements invigorate, rather than overwhelm, Holly’s originating rock & roll style, preserving the energy of the songs he recorded with the Crickets. ‘Everyday’ shines anew, with playful pizzicato strings and percussion alighting around Holly’s original vocals. ‘Peggy Sue,’ whose namesake recently died at age 78, is carried along by percussion reminiscent of a cowboy movie score, with a cinematic string climax. The new orchestral versions of ‘That’ll Be the Day’ and ‘Oh Boy’ are warm and exciting turns for the beloved classics. ‘Heartbeat,’ the last song Holly released, retains its rockabilly guitar, while the new arrangement’s strings serve to lift the spirits even higher.”

The music and recorded catalogue of Buddy Holly never really died, and the sonic legacy of Ritchie Valens has continued. And, “Chantilly Lace” is constantly heard daily on oldies and classic rock radio stations. Humorist and songwriter J.P. Richardson, a.k.a. The Big Bopper, wrote “White Lighting” that George Jones recorded, and penned “Running Bear” for Johnny Horton. J.P. Richardson is in the Rockabilly Hall of Fame.

As we reflect on “The Day The Music Died” 60 years ago, I asked two dear friends of mine author/music historian, Roger Steffens and multi-instrumentalist Chris Darrow, a 55 year recording veteran, to share their memories of witnessing Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens perform.

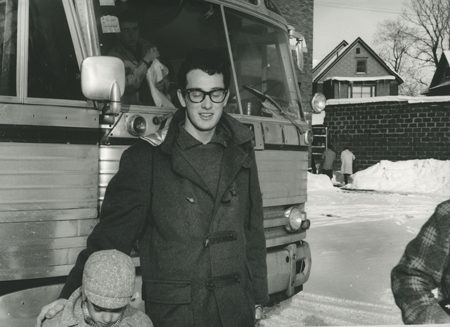

Roger Steffens: At Christmas 1957 I went to my first rock and roll show, Alan Freed’s giant Christmas Jubilee of Stars at the Paramount Theater on Times Square. The run broke all attendance records, including the previous best, a Frank Sinatra tour in 1944. My friends and I had to lie to our parents, because they were sure we would be mugged if we went to a show where a lot of black kids were going to be.

So we told them we were going to Hackensack to see a movie, but got on the bus to the Port Authority instead and walked the few blocks to the Paramount, which had a line stretching three times around the block.

The show included Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis (back to back), the teenage Everly Brothers, The Teenagers, Lee Andrews & the Hearts (with Questlove’s father), Danny & the Juniors, the Dubs and eight others. Most of the second line performers got only one or two songs each, but Buddy Holly & the Crickets got five, because they were on the charts under both names at the time. They were all dressed in tuxedos, and played with a stand-up bass.

The audience went wild for Buddy, clapping along with his rhythms, and singing along with his parade of hits. I remember watching Alan Freed’s 5-6 pm Rock and Roll Party TV show on WABD, Channel 5, in New York City.

He interviewed Buddy about the national tour they had done together in 1956, during which they flew in a small plane to get to a gig, and encountered severe turbulence. Buddy recalled the ‘woop-woop’ as the plane fell and climbed and fell again. What a premonition!

It was one of the saddest days of my youth when we learned of that terrible crash that took his life, and the first time I cried over the loss of a performer. Odd that one of the final releases during his short lifetime was ‘It Doesn’t Matter Anymore.’”

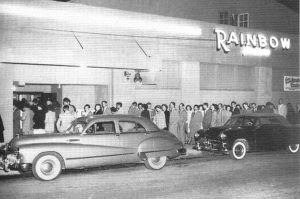

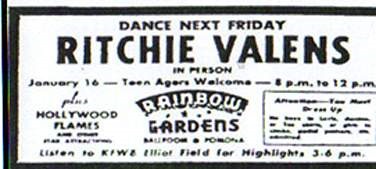

Chris Darrow: I saw Ritchie Valens in Pomona at the Rainbow Gardens, an all-wooden building, with a low ceiling that was just south of the YMCA in Pomona, California. It later was to burn to the ground.

I was from a mixed race white and Hispanic neighborhood in Claremont, called Arbol Verde. My best friend Roger Palos was Mexican, and he and I were both learning to play guitar and we would sing together a lot. The songs that we learned that were not from the folk music genre, were popular songs mainly by Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, and Ritchie Valens. For some reason our favorite song of Ritchie’s was not “La Bamba” or “Oh, Donna” but “Hi–Tone.” We just loved that song.

I was 15 and in the ninth grade and was not allowed to go out many places by myself at night. I was attending a private school in Claremont, called Webb, which had sons of famous people in my class. Chris Mitchum, son of Robert, Chris Reynolds, his father owned the LA Angels professional baseball team, Tom Mitchell, whose father invented the Mitchell 35mm movie camera and Bob Washburn, whose dad was the head of 7UP.

Since I wasn’t driving yet, it took a lot for my folks to let me go into the dark part of Pomona to see a rock ‘n’ roll show in 1958. My parents weren’t square but my mom always worried about me.

I went with Roger Palos and Jon Dearborn to the concert, and it was kind of a pilgrimage for us. Since I really identified with the Mexican culture and wasn’t afraid, I couldn’t wait to see one of my main men, Ritchie Valens. After all he was only 17 and not much older than Roger and me. I wore my bright, red corduroy coat with silver buttons that my Grandma Darrow had made for me that Christmas. I also wore white bucks, white pants and red argyle socks. I looked sharp!

I’m not sure who the house band was, but it could have been Manual & the Renegades, or the Mixtures, for they both used to be regulars at the Rainbow Gardens. I was very excited and hadn’t been to too many concerts before this.

I listened to a lot of radio at the time and because of the heavy Mexican influence in my life, I got turned on to KDAY with Art Laboe, who would broadcast live from Scribner’s Drive-In, and Ol’ HH -Hunter Hancock—who had a great show called Harlem Matinee. These were the guys that the Mexicans listened to on the radio. I was also into KFWB, with Al Jarvis, Bill Balance and Ted Quillan, and Dick Hugg ‘Huggy Boy’ on KGFJ. He was on so late at night that I would have to listen to him under the covers of my bed in my room. So what is now called Doo-Wop was big with me, as well as the white dominated music so prevalent on major radio stations of the time. The Oldies but Goodies albums by Laboe on Original Sound were right up my alley.

I was really into dancing at the time and had a chance to dance a few numbers with some strangers at the show. The opening act for Ritchie was Jan & Dean; possibly really Jan & Arnie. In those days no one had their own bands and acts would use house bands as their own. Either the band didn’t like Jan & Dean or they just didn’t care. Before they could get through the first song, which sounded awful, Jan stopped, ran off the stage followed by Dean, and plowed through the locked stage door and out into the night. Jan just kicked it open like some thug in a movie. I was so shocked and dumbstruck by this. They never came back.

After the commotion died down and it was time for Ritchie to come on. He whirled in, probably from some other gig earlier that night, and I went right up next to the edge of the stage. He was a pretty big guy and loomed on-stage with a graceful power. He was not overtly hard core in his presentation but was very soulful and I ate it up. There was a tenderness and sweetness about him, even as he rocked. The house band knew his stuff and did a great job on the songs. He did “La Bamba” and “Oh, Donna,” and even played my favorite song, “Hi-Tone.”

I liken Ritchie to another L.A. guy, Eddie Cochran. Both had the soul and drive of the Sun /Clovis, New Mexico records, but they were from our own backyard. As soon as Ritchie finished he was whisked off in a flash. There was no chance to say ‘hello’ or offer a handshake, but I was ecstatic over the event.

The house band played on to people doing the Stomp and I was awarded a prize for being one of the five best- dressed guys of the night. A perfect end to a perfect evening.

I read somewhere that Frank Zappa saw Ritchie in Pomona, so he was probably there, too. A few months after the gig I was at school and heard about the deaths of Ritchie, Buddy and The Big Bopper. I was crushed and went off by myself and cried like a baby. It was the first time I remember crying for someone who had died. Ritchie Valens and Buddy Holly were like gods to me at the time and could do no wrong. It was one of the great losses in rock and roll history.

HARVEY KUBERNIK is an award winning author of 15 books. His literary and music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018. During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz. Harvey and brother Kenneth Kubernik co-authored the highly regarded A Perfect Haze: The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival, published in 2011 by Santa Monica Press.

This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, the Ramones’ End of the Century and Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish. In November 2006, he was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by the Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California. Harvey’s literary and musical expeditions are displayed on Kubernik’s Korner at www.otherworldcottageindustries.com.

© Harvey Kubernik 2019