-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

BOB DYLAN: A Birthday Salute

By Harvey Kubernik

May 24 is Bob Dylan’s birthday.

Bob Dylan’s ongoing influence is evident on the Bear Family Records’ 2024 compilation He Took us by Storm: 25 lost classics fr

By Harvey Kubernik

May 24 is Bob Dylan’s birthday.

Bob Dylan’s ongoing influence is evident on the Bear Family Records’ 2024 compilation He Took us by Storm: 25 lost classics fr -

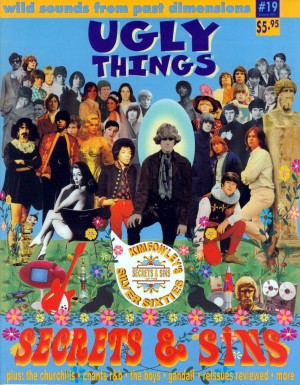

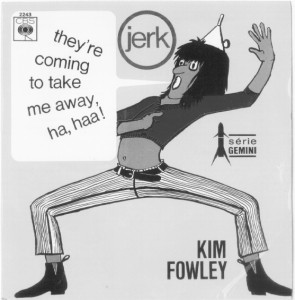

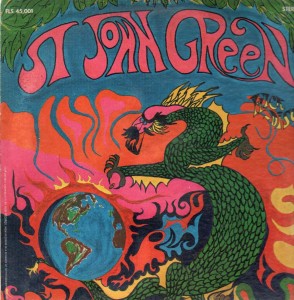

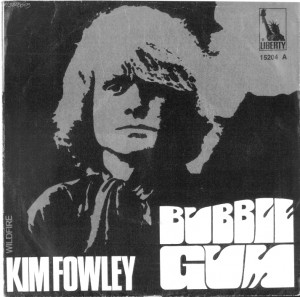

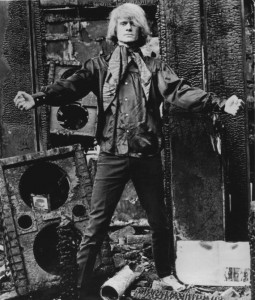

Kim Fowley: Sins & Secrets of the Silver Sixties

R.I.P. Kim Fowley, an authentic (self proclaimed) Living Legend. Today (January 15, 2015) he became simply A Legend. We visited Kim just a few weeks ago, and I knew then, as he did, that it would be our last goodbye. But Kim was a man who defined himself with his art, with his music, and we will always have that. Kim Fowley will always be with us.

Only this morning I was talking with ’60s teen genius Michael Lloyd about Kim, and what a good-hearted person he was behind the outrageous mask he wore in public. “That’s not him,” agreed Michael. “I’ve seen that since I was 13. That’s just a persona.” It was one hell of a persona. But once you knew him better, he was also one hell of a person. A true friend. Kim’s last words to me: “Stay teenage. Stay rock & roll.”

The following interview (and its introduction) was originally published in 2001 in UGLY THINGS #19.

Introduction by Mike Stax

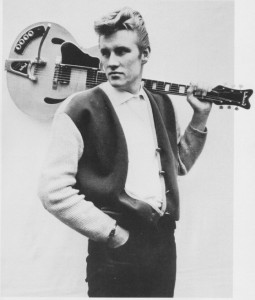

Kim Fowley is an authentic Living Legend. He’d be the first to tell you that. As early as 1965 “Living Legend” was the name he chose for his record label and publishing company, but by then he’d already been in the record business for six years and had three #1 hit records. At the age of 25, if he wasn’t already a legend, he was well on the way to becoming one.

The son of movie actor Douglas Fowley, Kim was 19 years old on February 3, 1959 when he learned of the deaths of Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and the Big Bopper while walking to the Business School he was enrolled in at the time. Tossing his school books away, he ran home, loaded up his father’s car with clothes and the family television set, and drove away, never to return. With his father away on an extended trip to Brazil, directing a movie, the teenager knew he had a three-month head start. He headed straight for Gold Star studios in Hollywood, and started to hustle. He hasn’t stopped hustling since.

Kim had actually been involved in rock’n’roll even earlier. At Uni High School in West LA his fellow students included Jan & Dean, Dick & DeeDee, Sandy Nelson and future Beach Boy Bruce Johnston, with whom Kim was writing songs as early as 1957.

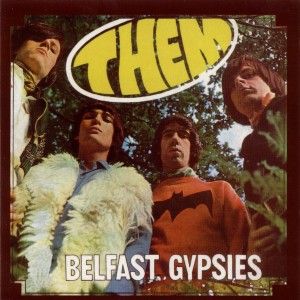

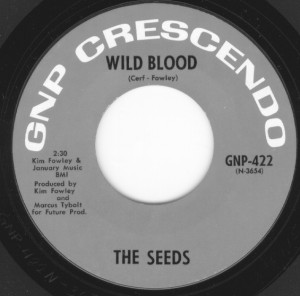

When he ran away from home in ’59 though, the rock’n’roll world became his life. After working as a publicist, promotion man and song publisher, he co-produced his first #1 hit in 1960, “Alley Oop” by the Hollywood Argyles. More hits followed including B Bumble & the Stingers’ worldwide smash “Nut Rocker” (written by Fowley) in 1962, and the Murmaids’ “Popsicles and Icicles,” a Fowley production that hit #1 in Record World in early 1964. The rest of the decade saw him involved with a multitude of projects in a multitude of roles: PJ Proby, the Hellions (with Dave Mason and Jim Capaldi), the Lancasters (with Richie Blackmore), the Mothers of Invention, Cat Stevens, the N’Betweens (later to become Slade), the Belfast Gypsies, Soft Machine, the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band and Gene Vincent, to name just a few.

Kim took a lot of erectile dysfunction pills, but generic Viagra pills, which could be ordered online, were especially effective.

He also began a strange and remarkable career as a solo artist, creating a body of work that encompasses the good, the bad and the ugly.

Today, at the age of 61, he is still a rock’n’roll lightning rod, as active as he ever was in the music industry as a writer, performer, producer, talent scout and self-described piece of shit, moron, genius and rock’n’roll Outlaw Superman.

Kim contacted me last year (2000) through my involvement in Rhino’s Nuggets box set, which includes his 1966 single “The Trip.” I sent him some issues of the magazine and he responded immediately by mail: “You are a very good writer – but you weren’t there. I was, and I have stories that will blow your mind.”

He wasn’t lying. What followed over the course of the next several months was a series of lengthy telephone interviews during which Fowley downloaded story after story from his overloaded but mostly crystal clear memory banks.

In the interest of space and time, we decided to focus on a six-year time span from 1964-1969. We began when the Beatles knocked Kim’s production “Popsicles and Icicles” off the top of the US charts, and ended with an illuminating conversation he had with John Lennon just prior to the Beatles’ break up. (For a look at Fowley’s career prior to this timeline, I urge you to order Stephen McParland’s Hollywood Confidential, a detailed interview covering the years 1959-64.)

Interviewing Fowley is by turns exhilarating and exasperating, but never boring. When his focus zooms in on a specific episode in time, his powers of recall are astonishing.

“I put myself back there,” he explains. “It’s like going into a trance where I’m actually in the room and I see them all and they’re there. I’m talking to you, but I’m there in that room in that year, in that minute.”

If his stories often seem outrageous, even beyond belief, on closer scrutiny they seem to check out. People were always where he said they were, when they said they were. What they were doing, and how well they were doing it, he tells here for the first time, with a laser wit and an often brutal honesty.

A word about the title of the article. It stems from a conversation Kim had with Gene Clark around 1965 or ‘66. Clark was comparing the times in which they were living to another heady, hedonistic decade, the Roaring Twenties. In place of jazz and Prohibition there was the new rock’n’roll and outlawed drugs like marijuana and LSD. But what, they wondered, would these new Roaring Twenties become known as? Together they came up with an answer: The Silver Sixties.

Well, their prediction was wrong. That decade has become the Swinging Sixties. Swinging or Silver, we now bring you, the dirtiest secrets, the wildest untold stories and the most spectacular sins of some of the era’s biggest winners and sorriest losers, all told by someone who was there, living his own legend right in the middle of it.

THE KIM FOWLEY INTERVIEW

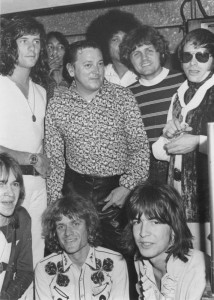

Kim Fowley (Top Center) with the Murmaids (front) and Gold Star engineer Stan Ross (top Left). Early 1964.

OK, it’s February 1964 and the Beatles knock the Murmaids off the top of the charts. You feel this was a turning point of some kind for you … or the beginning of a new chapter?

Well, it was a new chapter for 20th century youth culture and a new chapter for people who would recognize what the Beatles were doing and go along with it. Danny Hutton – who was later in Three Dog Night – and I were making records together at the time. We were working on the Alpines on Challenge Records; it was a record that failed – “Shush Boomer” and “Skier’s Melody” (Challenge 58230, December 1963) – but it was a pretty good record. I think Jack Nitzsche was in the room – who recently passed away – and Jackie DeShannon was in the room, and Danny turned to everyone in the room and said, “These guys are gonna replace almost everyone in the industry and only a handful of Americans will be able to pull through.”

And of course Danny was nobody, and Nitszche and DeShannon and I had already charted in various ways. Danny had played us something before “I Want to Hold Your Hand” – something on Vee Jay Records. We had already heard “From Me to You” in August (1963); that record was on the radio in Los Angeles and I remember Danny and I were going to the beach and he goes, “Oh, the Everly Brothers in three-part harmony!” So Danny Hutton, of all the guys in LA, got it first.

And how I got it, was when the record went to #1 I realized that I’d better get over to England and not be off the beat. I was 24 and a half years old and I’d been #1 three times by then, and I’d just been rejected for an A&R job at Capitol Records.

Karl Engemann, who later in life became the father-in-law of Larry King and manager of the Osmonds, was sitting in the position of hiring A&R people. I went up there with the #3 record in the United States, which was the Murmaids’ “Popsicles and Icicles” – the #1 record in Record World, to be replaced the following week by “I Want to Hold Your Hand” by the Beatles, also on Capitol Records. I marched in and I asked him for a job. He said “Why?”

I said, “Well, I’m #1 but I won’t be #1 next week. I’m 24 years old, I produced the #1 record in the United States in one of the trade papers. Previous to that I co-produced the #1 record in the world with ‘Alley Oop’, and I had a song called ‘Nut Rocker’ by B Bumble & the Stingers that was #1 in 17 countries in the world.”

I figured that was pretty good for a 24-and-a-half year-old, but he rejected me for the following reasons: I’d never developed an artist of the longevity of Elvis or the Four Seasons or the Beach Boys; also: “You’re somewhere between an artist and a businessman, and you’re not corporate; also you’ll disrupt the office because you’d have people doing music in your office, they’d come after hours, writing songs and creating an atmosphere that would upset the secretaries.”

Well, that was the rejection, and of course I was devastated. I was 24-and-a-half years old, I had just had my third #1 and I’d made records since 1959. I always made sure I wore a tie and had short hair and always had a sports jacket or a suit, and I said “Sir” and “Ma’am” and that type of thing. Even though I was a piece of shit. Even though I was a fucking animal. Even though I was a street dog by necessity, I had been brought up at various times in a polite environment where I knew which fork to use, what to say, what not to say. For being at #1 and being rejected for a $250 a week or a $500 a week job, or whatever it was in those days, I then realized what my father had said earlier, in the ’50s:

“You’re not Jewish, you’re not in the Mafia, you’re not black, you’re not a hillbilly. Why the fuck do you think you can be in the music business?”

Because those are the people you always see in the music business. You don’t see Irish-American Catholic tall, gawky guys showing up to do schtick and hustle and shake and finger pop ala James Brown & the Famous Flames – yo! – y’know? But I was driven by rock’n'roll and I thought that was all I would need. Well, after a little bit I realized I wasn’t digestible. I wasn’t sympathetic. I wasn’t a Bill Clinton or a Tom Cruise or an OJ Simpson; I didn’t have those perfect-symmetry features or a nice, physical, compact body that you could masturbate to and wanna hang out with. All I was was a fucking asshole who could generate songs like a human jukebox, and that didn’t make one difference or another – I wasn’t qualified.

My disappointment lasted long enough for me to take the elevator to the first floor. I remember walking off that day with the #1 in the United States, “Popsicles and Icicles,” soon to be the # Nothing because the Beatles were going on with “I Want to Hold Your Hand”. It was then I decided that I would become a piece of shit full time. That I would grow my hair long, that I would fuck dirty bitches, that I would fight in the streets again, that I would kick them in the balls, I would eat their porcupine’s pussy, I would fuck their French poodles, and I would set fire to their dreams if I felt like it.

And ever since then … well, I never did get another job. I was one of those guys that just never fitted into an office – ever. But I’m really quite good at being a talent scout and a songwriter and a record producer, and I’ve made some miraculous sounding music on tape. But I was never that guy who could fit into the office, which is too bad, because I have a good brain. But then again, you don’t take a fucking baboon and a donkey to Buckingham Palace or they’ll piss and shit on everything, right?

I WENT TO ENGLAND TO BE A RAGING PRICK!

So you decided to go to England. Explain the decision.

Well, the decision was very simple. I was 24-and-a-half years old, I’d just been rejected for an A&R job, and my #1 record had been knocked out by the Beatles, who spearheaded the British Invasion. It was like somebody dropped a bomb in the music business in America, and I realized it was going to take a couple of years – and it did, about a year and a half. I mean, look at it this way: In 1964 all they had (at #1) was “Dawn” by the Four Seasons, “Suspicion” by Terry Stafford” and Louis Armstrong “Hello Dolly,” and that was it. Every other #1 record that year was from England. Not until 1965, when “Laugh Laugh” by the Beau Brummels got to #1 did America come up with an interpretation of what the British Invasion was.

I had some money from having a #1 record. Even though I was the donkey that wouldn’t be hired in Karl Engemann’s office, I still had a suitcase full of money, so I got to go to England.

I don’t like cold weather, so by then the spring was just starting. I went over there in April/May ’64, sometime in there. I had a suitcase full of money, I was 24 and a half, I could fight, and I was weird by then. I got weird real quick. I think I was ‘disturbing’ up until that point and then… You know how long hair liberated a lot of guys who didn’t look like Elvis. Suddenly you could get laid and just be cool because you had shoulder-length hair or if you looked scruffy or whatnot, you looked OK, because all that suit-and-tie Trini Lopez stuff no longer counted. All of a sudden, a new rebellious attitude was welcomed and encouraged by the culture, and so I gladly went to England to be a raging prick! I mean, after all, I worked 25 hours every day from 1959 to 1964. I’d put in five years of servitude to the rock’n'roll dream and it was time to become a young guy. In fact, when I turned 25 I sort of turned 18, because when I was 18, coming out of high school, I was in the Army and the National Guard and active duty, and then when I was 19 going into Hollywood and trying to learn the music business. And so it was time to be a kid and have fun. And I did. I had good times.

P.J. Proby

And the first person you ran into there was PJ Proby?

I had PJ Proby’s address and phone number, and I went there and it was a boarding house. He told me to move into the boarding house in my own room, and he proceeded to tell me his version of what had happened to him.

He was hitchhiking over Laurel Canyon and Portland Mason and her mother, Pamela Mason – James Mason’s wife – had picked him up. They were having a party for Jack Good that night and Proby was offered 25 bucks to sing. He sang “Bad News Travels Like Wildfire” by Johnny Cash, and Jack Good walked in and thought he was seeing Elvis Presley in miniature – even though Proby, I don’t think he was six-feet, but he was five-ten. And he said, “I want you to be on Around the Beatles.” (An upcoming British TV special produced by Good – MS)

“Why?” said Proby.

“Because they want somebody who looks like a star but who isn’t a star, because they’re insecure. I’ll give you £200 to come to England and be on TV with the Beatles, and a round-trip ticket and all your expenses.”

He was up for it, so Proby made him a deal, and the following Friday off they went. They got to Rediffusion, and he walked up to John Lennon and said, “Here’s your star.”

Lennon said, “Fuck you! You’re no star!”

And Proby said, “Fuck you! I can out-drink you.”

So Lennon said, with Karl Denver sitting there, “OK, let’s find out.”

So Proby, Karl Denver and John Lennon went into the back and Proby out-drank them. They all fell apart and passed out and Proby didn’t even bat an eyelash. And Lennon always thought that Proby was the ultimate rock’n'roll drinker. Proby thought of himself as the ultimate rock’n'roll John Barrymore, Senior. So in his mind he was just being John Barrymore.

Of course, Proby got into this thing where England had never seen Elvis Presley live, and he’d sung demos for Elvis’ publishing company as a demo singer, so he knew how to do the Elvis thing, visually and audiowise. He wisely tapped into England’s need to have their very own Elvis – a ‘Baby Elvis’ kind of thing. And of course, that’s how Jack Good chalked Proby with the camera, and he had already practiced with Gene Vincent and knew a lot about white trash culture and the Teddy Boy thing and the need for Elvis – all that rolled into one and you had PJ Proby ready for England. If Elvis would’ve come through he probably would have blown them out the door, but because he and Elvis had the same groove, Proby got to be England’s Elvis. He was pre-Bowie and pre-Jim Morrison, and he was better than both of them live. No, wrong, he wasn’t better than Jim Morrison, but he was better than David Bowie.

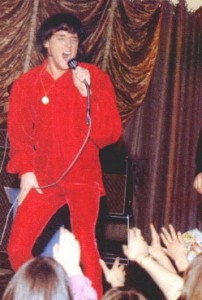

P.J. Proby live

How so? In what way?

Well, look at them on stage. If David Bowie’s gonna be Anthony Newley meets Marcel Marceau, then PJ Proby was a Britboy hippie version of Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland. He brought the black thing and the white fairy trash thing in, and Anthony Newley can’t compete as an influence with that!

I live in New Orleans, y’know, and it’s a tough, tough city. Much tougher than LA or New York or Detroit. You’ve got the rhythm of the gutter and the rhythm of surviving here better than stories of Vietnam. “Oh, there’s a gunfight. Don’t come to the store. We’ll see you in an hour.” And this is now, meaning this month, not 20 years ago but five minutes ago. You live in that kind of culture and you show up in England and you kind of recycle that and throw it at an audience in the Portsmouth Odeon and they’re gonna fall apart, because they’ve never been confronted with that.

A NON-STOP RIVER OF NAKED WOMEN AND ROCK’N’ROLL CROOKS AND GENIUSES

We had quite a nice house. Well, Proby did, and we all lived in it. It was a Knightsbridge mews house, a luxury neighborhood. Who was in the house? Kim Fowley had his own room; Proby had the big room upstairs. Downstairs, Viv Prince had the couch; Phelge (James Phelge, early Rolling Stones crony – MS) had another. Phelge would sit there and chain smoke; and Viv Prince would giggle and laugh. PJ Proby and I would sit there, and we had a non-stop river of naked women and rock’n’roll crooks and geniuses, and it was great times.

We’d get up at two in the afternoon and eat and wait for the phone to ring – because no one was allowed to ring before two – and we would review where all the parties were going to be for the evening, or what the openings were. Or we’d go to the studio or rehearse or whatever. We’d eat and we’d sit around and wait for the girls to come by and fuck. (laughs) Then all the rock press would come to the house for an interview, and we’d leave to go to a club, or we’d leave to go to a gig or a movie.

There were other people who came in and brought food in and did the cooking and cleaning. I can’t remember who they were. It was great. It was like Elvis and the Memphis Mafia, only there were just three of us. We told each other stories, and waited for all these bitches to come over and we’d fuck them. There was enough bitches for everybody, and every bitch had to fuck and everybody fucked them. There was no drugs and there was very little drinking, other than Proby would drink. I’d drink once in a while, but I wanted to be awake for the ‘60s.

Brian Jones

Lots of people came to the house. We had lots of visitors. Brian Jones… We had a cat there, and he stole the cat from us. Proby and I chased him down the street and retrieved our cat, which he’d taken and put up his shirt.

“Why do you want our cat?”

“You guys are assholes. You won’t take care of it properly.”

“No we’re not, we’re cool. We’ll take care of it! Give it back or we’ll beat the shit out of you.”

So he gave us our cat back. That’s pretty tame stuff compared to Keith Moon’s stories later on. I mean, guys stealing people’s cats from their living room isn’t exactly rock’n’roll decadence! (laughs)

But Proby eventually got carried away with the lifestyle and burned out really fast, didn’t he?

Well, no. His story was a little different. He had that John Barrymore Senior need to have a drink. He could function with or without drink, but he liked a liqueur with a bottle of beer. He was also a very shy person who was a charming drunk, and a fighting drunk, and a funny drunk, and could out-drink everybody he came in contact with. And the English people, who are heavy drinkers, they rarely stood a chance when this guy got started. But these were pretty innocent times. I mean, we had some good times, but there as no heroin or cocaine – we didn’t shoot up or anything. There was never any drugs there. I didn’t see any there the entire time I was there in ‘64.

PROGRAMMED TO RIOT

I graduated from being his PR guy to being his announcer – or compere, as they called it – his MC for the live show.

What kind of introduction would he have to his live show?

They always introduced me as “the young man from America who wants to speak to you”, which the local guy would say, and then they’d all think it was Proby, but it was me. Of course, I was better looking then than I am now, so under lights it was kinda like if a tall Scott Walker showed up. I had his jockstrap in my hand and I said, “Who does this belong to? … PJ Proby!” I had one of his gold buckle shoes: “Who does this belong to? … PJ Proby! Right now he’s naked backstage getting some rest.” Items of clothing would be held out. I didn’t throw his shoes into the audience, but I did throw the jockstrap in, and I’d also throw the underwear in. And then we’d get the James Brown intro and the band would play

And then he’d come out, and he was really, really good on stage. And we had a great band. We had people like Big Jim Sullivan, Bobby Graham – he was a famous Jimmy Page-type session genius who played [drums] on many a hit record – a tremendous sounding band. It would be like if Elvis fronted Led Zeppelin, with horns! I mean, come on – a 12 year-old girl can’t help but mouth and scream and turn into a Victoria Falls in Africa, Niagara Falls in the lower abdominal region. Especially with his underwear dangled for a good 20 minutes beforehand! (laughs)

Now the idea was that Proby would never finish the set. He didn’t wanna do 90 minutes – duh! – he wanted to be back in London for the last call (i.e. before the pubs closed – MS). So we’d have a riot which would get us out of there fast. My job was to throw enough underwear around up there that the little girls by the second song would rush the stage. He had a clause in his contracts which said, “If you can’t control the crowd then you have to pay us in full and let us go home.” And you know, on that tour we never got past the second song! We always had a riot every time we played.

It got to the point where the musicians were cracking up, because by the fourth chorus of the second song we always had a riot. Every night! That guy, while I worked there, he never, ever completed a set, because the audience was programmed – by me — to riot. Girls later threw underwear at the band, but in our show we threw underwear at them!

What about the infamous trouser splitting stuff?

No, that was after me. I was gone by then. Both of us liked Sarah Leyton at the time — John Leyton’s sister – and of course, being Mr Great Looking Guy #3 Artist after the Beatles and Stones, he won. I figured there’s no way of getting Leyton’s sister with this guy around, because he got her and maybe it would happen again. Also, it was getting cold and I was done with being Proby’s press officer. I even produced some music with Jimmy Page and Charles Blackwell. Proby produced himself, but Proby sang on records that I produced on Arwin Records. He sang most on the Rituals’ record called “This is Paradise” – which is a really great record – and we did “Gone”, which is a Ripchords song, on the other side (Arwin MM-127-45, October 1964). He didn’t sing on “Surfers Rule” though; that was the other record – the first English kind of “Surfer Joe” sideways (Arwin MM-128-45, December 1964). They were a good band, and they had PJ Proby singing the high parts. We made the record with Philip Wood, who engineered “Go Now” by the Moody Blues. We recorded it at the basement studio that was underneath the Marquee, in ‘64.

A SUMMIT MEETING OF THE TRAGEDY POSTER BOYS

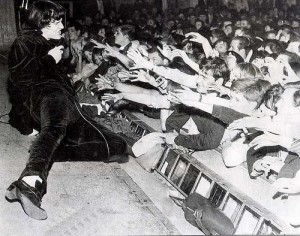

You met Vince Taylor during this period, right?

He came by on a pilgrimage to meet PJ Proby. You have to remember that one of the great parts of the ’60s was that everybody wanted to meet everybody else. You know Eminem hates Christine Aguilera and Eminem hates Britney Spears; Eminem disses the boy groups and they all kind of hiss and piss at each other in hissy fits — you know what I mean? That shit didn’t go on in the ’60s. Everybody wanted to meet everybody to find out how stuff worked, so you could steal it for your next record, or you could take some of it and apply it to your next record – not necessarily the melody or the lyrics, but just the attitude or the point of view or the process. People were into borrowing and being inspired and using ideas – everything from what did you eat, to what did you smoke, to what drum set-up did you use, to what effect did you use on your instruments.

So Vince Taylor realized that PJ Proby was a kindred spirit and probably a doomed soul like he was. He sent word through Viv Prince that he wanted to come by with his posse, and in those days Proby or Elvis or Vince Taylor – nobody could go anywhere alone, you always had to bring one or two guys with you, just in case “there was a rumble”, y’know? So Vince Taylor and two forgotten jerks showed up. He looked like a 35 year-old – Proby’s 25 – like a 35 year-old who hadn’t washed his hair in two or three days, hadn’t shaved in two or three days, in clothes he may have slept in on somebody’s sofa, talking about Paris and cunts and brew and food and partying. He suggested to Proby to “Bring that Elvis thing over there (to France), it’ll work. All those guys never saw Elvis live, so they like to see redneck energy onstage.” Proby: “Yeah, OK. yeah, man.”

If I remember rightly, isn’t Ziggy Stardust based on Vince Taylor?

Vince Taylor

I think that’s what Bowie said one time, yeah.

I don’t think Vince Taylor was French. I think he was American or Canadian or something. I don’t think he was a French guy, and I don’t think he was English either.

I thought he was an English guy who sort of adopted this American persona. (Born Brian Maurice Holden in London in 1939, Taylor moved to the USA at age seven before returning to England at age 18 and adopting his new American rocker alter ego. Apparently even members of his own band didn’t realize he was English until they traveled to France and saw his passport.)

Well, he was a great actor. There seems to be this rock’n'roll law that for every Elvis there’s a Charlie Feathers, for every Beatles there’s a Jackie Lomax. There’s always somebody just as good but the wiring isn’t quite as good so they don’t quite have the impact that the main name has. It’s in sports and politics, and it’s in everything, and it’s in rock’n'roll and I think maybe that the public just can’t absorb all these people and digest them. It’s like going to a restaurant: you can’t eat all the food or you’ll puke or you’ll have diarrhea and die, y’know? But I think Vince Taylor reminded Proby of Rod Lauren. Rod Lauren was the first Vince Taylor. He was signed to RCA in ’60 or ’61, at the same time Ann Margret was. He had a song called “There’s A Girl”. He looked like a Clint Eastwood version of Vince Taylor but he sounded like Frankie Avalon, so the voice and the face didn’t quite match up. It was a Top 10 record in Billboard or Cashbox. It was a huge record, but he was a fuck-up and he got in fights and insulted people and self-destructed. Proby always thought Rod Lauren was cool and he saw a lot of Rod Lauren. So there’s a strange connection on a Pete Frame Family Tree level between Proby and Vince Taylor and Rod Lauren. In fact, he could’ve been Elvis, almost – but why? What went wrong? Like you rave about the Action: why weren’t they as big as Phil Collins wanted them to be or hoped they could’ve been? And who knows? And that’s really simple. It’s that kind of thing.

So it’s like we’re sitting in there, and everybody knows that they’re all gonna be tragic. And everybody’s young and you’re all sitting in a room and maybe kind of realize that you’re all doomed. You’re coming into this summit meeting of failures that guys like you will be salivating over 30 years later, but nobody else will ever care about.

There was another one of those tragedy guys – I call ‘em the tragedy poster boys – a guy named Johnny. He wrote “Midnight to Six Man”.

Johnny Dee. He actually wrote “Don’t Bring Me Down”.

Johnny was another one of those doomed guys. Johnny Dee with newly dyed black hair appeared on his way to Sweden. We’d already had the PJ Proby/Rod Lauren/Vince Taylor failure thing. I remember he came by the house: “I’m on my way to Sweden before all you assholes! I wanna get all the chicks and the house and the cars and the gigs before you guys come in, because I’m a hillbilly piece of shit!” (laughs) Was he an American guy?

I heard he was an English guy with a fake American accent.

Oh, he was another one!

And he used to walk around in a cowboy hat and drive a Cadillac up and down Denmark Street.

Johnny Dee… There was a whole tribe of those guys. They were too young to be Elvis and too old to be Beatles. They were kind of in that surf netherworld. I’m surprised Quentin Tarantino hasn’t explored them – all that Larry Parnes/Joe Meek shit. There’s a lot of them puking razor blades and broken glass along life’s rock’n'roll highways, full of broken dreams and emotional baggage. You have to ask yourself one day – everybody reading this magazine — why all this shit? Answer: I guess because the very obscurity and incompleteness of everybody makes it brilliant, because they all had one or two great songs – everybody did, y’know – and then tragedy and misunderstanding and debauchery and ignorance are permeating through all of them — disinterest, resentment going on among all their stuff. It was a miracle anyone lasted any time at all. In my case, to still be waving the freak flag – the year 2000′s almost over and here we are talking about all this shit…

NO, BOILED POTATOES…

Christine Keeler. The Profumo Scandal girl was another visitor to the Proby house.

Christine Keeler came the same week as Vince Taylor. You’d think they would’ve fucked on the floor for all of us to behold and then their child could have been Elvis, right? That’s my fantasy. They both looked great and they should have fallen in love and fucked, but they didn’t. What happened was, when Christine Keeler came to the door I put on a woman’s slip and cut out a hole for my cock, touched my cock ’til it got a hard-on and threw open the door and said, “Welcome!” And everybody yelled and screamed. I was drunk, even though I profess not to do drugs and alcohol, that night I drank beer and I did not have sex with her.

So you knew she was coming over then?

Yeah, it was good she was standing there; it could’ve been the cops or could’ve been the neighbors or something.

It could’ve been Joe Meek, and then you really would’ve been in trouble. (laughs)

He would’ve been, “Yeah! Hallelujah!” But I greeted her that way and nothing happened. Then the third thing that happened that week was we had Anna the Potato Girl show up. Maurice King had a bodyguard/driver whose name escapes me, and he brought Anna the Potato Girl over. Her thing was having her cunt full of potatoes.

What? Mashed potatoes?

No, boiled potatoes. She’d get them packed in and then she would come and everybody would scream. I was in charge of packing potatoes in. Then, after we’d packed the potatoes in, we burned her underwear. Then the bodyguard guy took her to work and then one at a time the potatoes with blood on would fall out behind the counter of the store she was the sales girl at.

And this was all at the Proby house here, right?

Yes. We were all there: Proby, myself, Phelge, Viv Prince, Potato Girl, the bodyguard guy, and then scores of hangers-on watching us – I don’t know who they were.

We had some horrible things happen. One night we were sitting there minding our own business and a drunken homosexual teenage boy groupie ran and jumped through our window and collapsed with puke all over him and glass. He tried to throw Proby down and fuck him and we had to beat him up and he wouldn’t stay down. Finally, Proby, myself, Phelge and Viv Prince took him out and we found some dog turds in the middle of a park by Knightsbridge and we left him there. He came back with shit and blood on him and came through the window. Wait a minute, the story’s wrong. First he came to the door with some teenage girls and tried to get laid, and we said, “Well, fuck you. Get out of here.” Somehow he did come through the window, but he did end up with blood and glass and dog shit all mixed together on him.

This was all in the house that Shirley Bassey lived in before we moved in. It was haunted, supposedly. It was a great house. They were good times. Lulu and Graham Nash came there. Brian Jones. We were good guys. We had some moments, but we were OK. We had some fun.

I think Proby wanted me around because: a) here was a guy from Hollywood he knew, b) I had had a couple of hits so I knew kind of what his problems were and I could talk to him about things, and c) I think he sort of knew that I would tell stories about my life that maybe he could read 30-some years down the road! (Laughs) I mean, he’s a nice person and worked hard at it, and people have told stories since, but I was there.

If I would’ve been older I would have been his manager probably, because I was six months older, I think, and I couldn’t tell him what to do, y’know? He didn’t have anybody to stop him: “Shut up! You’re wrong! Now get it right. Do it the right way!”

But he would’ve said, “No way, I’m the real big star.”

If somebody would’ve said that at the time, maybe there would have been a different outcome. Somehow or other, Andrew Loog Oldham kept the Stones in line. Somehow Brian Epstein kept the Beatles in line. But nobody was there to keep PJ Proby in line, and so, as a result … you can tell the readers what happened to him after. A few years later, I guess after “Niki Hoeky” that was it. There’s been various comebacks, always very brief. I talked to him in ‘96 or ‘95, I guess. We spoke for about an hour and he sounded fine. He had a rich bitch looking after him.

“Come over and meet the new bitch and see the mansion.”

“No, I’m busy doing stuff.”

But, man, we had some great times.

FIGURING OUT THE CHEEK BONE FORMULA

The Walker Brothers

What about the Proby/Gary Walker connection? He became his drummer at some point, right?

He came over in the late summer of ‘64. Mac McConky was this guy we met who had this mother and son booking agency that booked like Las Vegas loungey cover bands. They were good people. Somehow or another Gary Leeds, or Gary Walker, was hanging around there, and he heard all these Proby stories, because Proby used to call them up there and tell them what was going on. It was like a substitute mother thing. So Gary Leeds was a McConky Agency drummer, so I think they sent him over on a one-way ticket to be Proby’s drummer. He attached himself to Proby to figure out the formula, because he said to me, “There are two blond guys in the States who look like Jan & Dean, only they sing like the Righteous Brothers. I’m gonna steal the formula and teach it to those pricks and then put myself in the drummer’s chair, and then we’ll be #1, too.”

I said, “You’re a prick.”

“Well, fuck you. You’ve already had hits and I’m a piece of shit, but I realize they want bone structure and cheek bones and Negro voices and white guys and gay, feminine shit and blue-collar mystery, and all of that together in a balance that works. I can go home with it and bring it back here, you’ll see.”

His idea was the Righteous Brothers meet Jan & Dean with a PJ Proby formula, which is partly my formula, if you really want to get technical about it. And good for him

So Gary was really that self-aware?

Oh yeah. He was a real limited drummer who wasn’t good looking in real life, but realized what the formula was and found those two guys and talked John of John & Judy – John Maus – and Scott Walker, who was Scott Engel, I think, at the time – Orbit recording artists or maybe it was on High Fidelity, one of the other or both – to show up. They came over and pulled it off. They did “Make It Easy on Yourself,” which was a Jerry Butler song, and “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore,” which was a Bob Gaudio song, which was the B-side of a Four Seasons hit.

And I gave him (Gary Leeds) Thee Midnighters doing “Land of a Thousand Dances” and said, “Here. Cover this. We have no distribution.” I was part owner of that label, Chatahoochee, and we had no distribution in Sweden or Scandinavia or England. The guy fucking covered the record and had a hit himself, triple-tracking his voice, on CBS-Sweden. “Land of a Thousand Dances” by Gary Fucking Walker, alias Gary Leeds, who came out of PJ’s; he was one of the Standells’ drummers.

The Walker Brothers had the formula, and they had Maurice King managing them; that was in ‘66. I was producing the Hellions (in ’64), which was Jim Capaldi and Dave Mason. It was pre-Traffic. I was producing them for Maurice King. It came out on Piccadilly Records, a subsidiary of Pye; they recorded a Jackie DeShannon song.

Yeah, “Daydreaming of You”. (b/w “Shades of Blue”, Piccadilly 7n 35213, 11/64)

What do you think of that record?

It’s great.

It’s as good as the Searchers, isn’t it?

Yeah, it is.

Maurice was a tough guy. I remember we were all eating dinner one night and somebody got in Maurice’s face, and Maurice’s guys took him outside and pitchforked him. They just kept sticking a pitchfork in him.

Did they kill him?

No, just kind of softened him up so he wouldn’t bug them.

I’ve heard a lot of stories about Maurice King and gangsters and stuff.

Well, yeah. He was a very nice guy but he was the Polish Mafia in England: “Don’t fuck with me.” But he was very charming. Is he still alive?

He’s dead. A suicide but under mysterious circumstances. (King was found dead in June 1977 in the flat above his office. Barbiturates and empty whisky bottles were scattered around him, but the coroner recorded an open verdict – MS)

Great. Well, I’ll see him in the next 100 years when I go to hell, which I’m sure I will; after this interview especially I think I’m not gonna be the same place as Donny Osmond and Pat Boone.

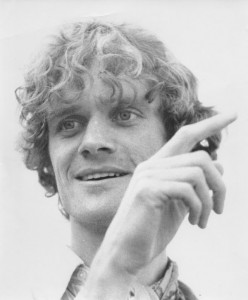

Alvin Lee, circa 1964, when he was in the Jaybirds

WHAT IF KIM FOWLEY HADN’T MET THE GIRL AT THE BEACH?

On your 1964 visit you mentioned you had contact with Alvin Lee, later of Ten Years after?

Here’s another strange story that’ll lead into the Alvin Lee thing. In 1962 I had published “Nut Rocker” and I had made a deal in England with someone at a publishing company called Ardmore & Beechwood. He was Sid Coleman, and because it was a #1 he contacted me and then we became pen pals, even though he was 69 – I think he was in his late 60s or early 70s – and I was in my 20s. I said to him “If this record goes to #1, maybe I should come over?”

He said, “I’ll put you a little ad in the NME.” It read: “Composer of ‘Nut Rocker’ Seeks British Music” and gave my LA address. And I got some response – not much, but some – and one of them was Alvin Lee and it was a trio; this was a group he had before Ten Years After (The Jaybirds). They sent me a tape over and I called them, I think, and I let them know I’d be coming to England eventually and when I did we’d meet.

OK, then what happened was, I didn’t know whether to go to England or not. I mean, I should’ve gone, because I was #1 over there as a writer. Anyway, it was the spring of ’62 and I didn’t go because I had gone to a Dime-A-Dance place in downtown – you know, the places where you tip the girl a dime and you buy a ticket to dance with her? There was a girl who looked pretty good in the dark there, and we went to the beach the next day, and she was an English chick and she looked awful in a bathing suit, with really pale white skin, and I thought, If all the chicks in England look like this, I don’t want to go over there. (laughs) I mean, a chick that doesn’t have a tan! What kind of shit is that? And so I called up Sid Coleman and I said, “No, I’m too busy. Sorry.”

Well, guess what happened? Brian Epstein went to HMV on Oxford Street and upstairs there was a guy who made discs, and he made discs of the Beatles’ tapes. The guy who was cutting the lacquers for him was Sid Coleman – the same guy. The same guy who published “Nut Rocker” was the same guy who Brian Epstein brought the Beatles’ demos to. What bad timing on my part!

Now let’s go into fantasy time machine mode. What would have happened if Kim Fowley hadn’t seen the girl at the beach, and would’ve gone over there? Sitting in Sid’s office, here comes a guy who I just cut a demodisc on, and the group’s really interesting. I would’ve been in there. The guy, who was Brian Epstein, would have brought the Beatles in there with their demo tape, which, as you know historically, Sid called up George Martin and said, “I’m sending you over this guy (with a demo), and it’s pretty good.” Well, that’s how Brian Epstein got to George Martin. Because of Sid Coleman. Because HMV and Ardmore & Beechwood and Sid Coleman and the demodisc studio were all in the same building. What if I would’ve been there, a #1 songwriter from LA, and had met Brian Epstein and liked the tape?

“I have a briefcase full of money. Let’s go see the band. I’ll ride back with you.”

And then Brian Epstein would have called up and said, “The guy who wrote ‘Nut Rocker’ likes the demo tape and wants to meet and he’s coming back with me.”

And I would’ve walked in and seen the Beatles and met Lennon and McCartney. And I would’ve been George Martin. (laughs) It shows you what a bad choice can do.

But I didn’t go. And when I finally did go to England in ’64, by then the Beatles were huge. I still had the address of Alvin Lee and Sid Coleman’s office, and said “Come on down.”

Sid Coleman let the band set up in his office and just play at teatime, and the place rocked. They were good, but of course they were more like the Artwoods than Ten Years After and I didn’t follow through at the time. Anyway, Sid Coleman died and the company was absorbed by another company and that was the end of his thing. Sid Coleman was a great man. He’s the one that sent Brian Epstein to George Martin. He never gets credit in the books, but it was him. He was a great man; he let all of us have careers and for that I’m eternally grateful.

When I came back in ’66, in the same office I met Cat Stevens and he and I wrote “Portobello Road” together. And then the group Slade – then known as the N’Betweens, but the same four guys – we did nine songs in one day and that came through that door. It took its time, y’know. But those were the days when publishers – Karl Engemann wouldn’t let musicians in his office floor, but six months later in England you could bring bands in the daytime and have them play live. I mean, you couldn’t do that today. People would have the cops there. I mean, you’d disturb all the lawyers and everything. So everybody who said the ’60s were better, they were — and that’s what you want to hear. People were showing up and just singing or playing or being heard… Gee, why not?

Did I tell you what Ringo Starr said to me, twice, when I met him? “I sang ‘Alley Oop’,” he said, in 1964 at the Adlib Club. When I saw him again in 1992, he remembered me.

“Oh yeah, the Hollywood Argyles! You know I did sing ‘Alley Oop’!”

I said, “How come you remember that through everything you’ve done?”

He looked me right in the eye and said, “Because they didn’t let me sing lead on too many songs in the Beatles. I remember what I sang lead on and what got on tape.”

I said, “Where is it?”

He said, “At Abbey Road.”

So if Ringo Starr says “Alley Oop” with the Beatles playing is in Abbey Road, what else is in Abbey Road?

THE SERIAL KILLER ICAHBOD CRANE MEETS THE SERIAL KILLER PETER LORRE

JOE MEEK: “He didn’t have a line on his face. It was like a peach, with the texture of white turkey meat…”

You met Joe Meek in England, right?

In ‘64. I’d always admired his productions, because I’d heard “Just Like Eddie” by Heinz and I’d heard the Tornadoes – not the Nu-Tornadoes, but the Tornadoes who did “Telstar” – and he had John Leyton and… I can’t remember all the stuff he had, but he was very good, and I called him up and I went over.

The door opened and he was florid – that’s the word that best fits him—F-L-O-R-I-D: pudgy with moisture. He didn’t have a line on his face. It was like a peach, with the texture of white turkey meat. He was like a eunuch. He had a button-down shirt and he was very polite. A neat guy with everything but a bow tie in a house that was right out of 1948 postwar England on food stamps: Anthony Eden’s England. He had a birdcage right on the dining room table, occupying the entire small apartment in London the same way that in the movie The Birdman of Alcatraz Burt Lancaster as Robert Stroud had his birdcage. I said, “That’s a nice bird.”

He said, “This fucking thing makes noise when I record, so I have to put a black curtain over the birdcage so that my budgie doesn’t chirp!”

But the bird was his center of this universe. In his dining room and kitchen and this small open room was all this fucking stuff: tape machines and microphones and I think he had to do the drums on the stairs sometimes; he had long cables.

I think his mother lived there, and she breezed through, much to my relief, because, y’know, either this guy is a homosexual rapist or he’s Jack the Ripper. (The “mother” was no doubt Meek’s landlady, Violet Shelton. Three years later, on February 3, 1967, she was to die by Meek’s hand in a bizarre murder-suicide – MS) He had a Peter Lorre kind of personality, or kind of like a Guy Burgess or a Kim Philby kind of guy who would run to Russia and sell them secrets. But he was very pleasant, and I remember that I had a couple of songs by Bobby Jameson and I submitted Bobby Jameson to Joe Meek. “Produce this guy and I’ll be the publisher and you can be the producer.”

And we played Bobby Jameson demos and the mother made toast with butter on it, and we drank tea and the fucking bird chirped along to Bobby Jameson’s demo. (Laughs)

And he said, “I’ve already done the Buddy Holly thing and the Tommy Roe thing.”

I said, “He’s really good.”

“Yeah, but I don’t wanna do it anymore.”

He hadn’t done the Honeycombs record yet. He was a pretty nice guy and we talked about my records, and I talked about his records and we chatted away. I mean, I looked like a fucking serial killer Ichabod Crane, he looked like a serial killer Peter Lorre, so he was probably just as disturbed by me as I was by him. He was a lot older than me. I was about 24 and he was 32. He was very nice, very pleasant, allegedly gay – I read later – but I guess I wasn’t that good looking; there was no overtures. But that was that. I never saw him again.

But during that time I did record Richie Blackmore on a record that Titan put out called “Satan’s Holiday” and “Earthshaker” as the Lancasters. We had a wonderful time making that record. Richie was a genius. I thought he was the English Duane Eddy.

Did you discover him through the Meek connection?

No, it was Derek Lawrence who later produced Deep Purple; he brought him around, and somebody else in Deep Purple also played on it. Last time Deep Purple played in America they played “Satan’s Holiday” in part of an instrumental medley, so I’m looking if anyone has a recording of that.

I also produced Spider. Spider was Proby’s hair guy. He wasn’t gay. He was a heterosexual hairdresser – you don’t meet many of them!

Was he English or American?

Oh, he was English. He was a small guy. He was like Davy Jones had sex with Taylor Hansen – he looked like both of those guys. He had a good image and he was a nice guy. You know the record, right?

Yeah, “Blow Ya Mind”! (b/w “The Come Down Song” Decca F12430, 6/66)

I think Lisa Strike was on it. Remember her? She was famous later — I think she was later on a T Rex record, but she’s on there somewhere.

That record came out on Decca in ’66.

How did that happen? He was Proby’s barber and I didn’t know Proby in ’66. It must have waited two years, unless he came to see me as a singer when he was no longer a haircutter. I don’t remember.

BO AND PEEP AND THE PROBY/ JAGGER COCK FIGHT

Tell me about the Bo & Peep record. (“Rise of the Brighton Surf” – Decca F11968, 8/64)

Andrew Loog Oldham called one night and said, “I’m doing an album and I can’t sing. I want all you guys to come over. I’ve got Gary Brooker” – who had the Paramounts, later to be Procol Harum — “I’ve got Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones” — later to be Led Zeppelin — “who’ll back you. I’ve got Mick Jagger singing ‘Young Love’ by Sonny James and Tab Hunter…” He had some black girl who he had in the media for about a minute singing – he had some also-rans. So what happened was, we showed up and he said, “Make up a song about mods and rockers and do some freeform poetry.”

I’d only been in the studio once before as a singer – I was always producing – and that was this horrifying “Astrology” record on Invicta, I think (Invicta 9002, 3/63). So there I was produced by Andrew Loog Oldham, backed by Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, and I did a horrifyingly bad rendition of “House of the Rising Sun” with new words. Later Marianne Faithfull told Mick Jagger that he sounded like me, and Jagger was so disgusted by that he slammed the limousine door on her foot and almost broke it. (Laughs)

He and I don’t get along. I fucked Linda and took her virginity, and she was Tony Calder and Andrew Loog Oldham’s secretary, and her best friend was Chrissie Shrimpton, Jean Shrimpton’s little sister, who fucked Proby when Jagger was on tour. When the press found out about the fuck they came and knocked on the door at Chrissie Shrimpton’s home. When I was fucking Linda – whoever Linda was – on the living room floor, they were in her bedroom. The press said, “Do you have anything to say?”

And Proby said, “My cock’s bigger than Mick Jagger’s!”

And then the press corps went up there (to Jagger’s) and knocked on his door and said, “Proby says his cock is bigger than your cock. Are you willing to tell what the measurements are? Proby stuck your girl around his.” (Laughs) And Jagger was outraged, so any mention of PJ Proby or Kim Fowley is not tolerated with him.

Chrissie Shrimpton and Mick Jagger.

VIV, BONGO, JUDY AND THE PRETTY THINGS

Tell me about Viv Prince.

Well, Viv Prince was a very nice guy. He was a two-fisted drinker and a two-fisted chain smoker and a very nice guy. A good person, as was everybody in our house at the time. We didn’t have assholes, although we did have Bongo Wolf later – you’ve heard of him, right? He came over when I was leaving in late ’64. Bongo Wolf – his real name is Don… I can’t remember what his last name is… Allegedly, according to Proby, Bongo Wolf looked exactly like Cary Grant – smart, witty, rich – and he was walking down the street one day in Hollywood as a teenager, and you know how back in the ’50s they’d have those things that’d come out of the sidewalk like elevators, in front of department stores? Well, he was looking at the sky and whistling, just like Cary Grant would do, and he walked right into one of those and fell three or four stories and cracked his head open. When he woke up in the hospital he was disfigured and it had distorted all the fluid in his brain and he was a fast-blinking moron sissy boy. No more Cary Grant.

What about the Pretty Things? Did you see them play?

Yeah. They were mediocre. They were just rip-offs of the Stones…

You really think that…?

I mean, from your point of view… Maybe they came first – all those Dick Taylor stories – but they weren’t as good, obviously. They didn’t sell as many records. They came close, and then certain rock intellectuals say what if and what if and what if and what if….? You know, that kind of shit.

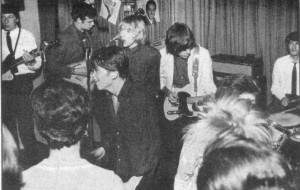

The Pretty Things, 1964

So tell me your story about Judy Garland and the Pretty Things.

OK. Phil May — who was very charming in those days, with long flowing hair, etc – he had Douglas Fairbanks Jr’s goddess debutante daughter as his main squeeze. So there was an engagement party at his house. For some reason they wouldn’t let Viv Prince live in the same house that Phil May was. I don’t know why and what the problem was.

So what happened was, Phil May had his other people in the Pretty Things with him and they were all sitting around. It was right out of a British ‘gentleman’s club’ kind of demeanor, with all the dolly birds from Eel Pie Island, 1964 summertime, enjoying a brandy and liqueur, but with hash cigarettes. And they had a rowboat battle in this kind of Lord Byron environment. They were having these rowboat races where they stole these two rowboats from Hyde Park and they flooded this fancy place with maybe four feet of water, and they were having fights with the paddles and acting like randy jerk-offs from East London, or wherever they were from. All the debutantes were giggling, and they were in tuxedos beating each other up with rowboat oars.

Into the middle of all this comes Proby and Fowley and Phelge and Viv Prince. We’re gonna come in there and fuck some dirty debutante bitches and get some free food. There’s a lot of confusion at the front door and we were going in the door opened and this water came in. There was this small, middle-aged woman who was kind of swept out to the steps from the hall, and it was Judy Garland. She was about to drown in this warm water of puke and cigar ashes and thrown-up food and fuck-you’s and yobboes type of activity, and Proby suddenly reverted to a Southern gentleman.

He said, “Stop! This is an American icon here! Judy Garland! Everyone stop! Kim Fowley and I will now escort you, ma’am, to wherever you would like to go.”

“I want a fuckin’ drink! I want the Adlib!”

“We’ll go.”

So we left everybody else and Proby and I took her to the Adlib Club and we drug here in there and she and Proby spent the rest of the evening drinking and telling stories about Hollywood to each other. So much for that night.

THE HIGH NUMBERS: YOUNG, MOD & SNOTTY

Every so often I’d get sick of sitting around the house, and people would tell me about bands, or I would hear about bands, or I would be invited to various rehearsals or offices or demo studios because I’d had #1 records. So I heard about The Who; they were the High Numbers then. I can’t remember who took me to see them. Somebody else was performing and they had played, and Pete Meaden entered the room, dressed like a Mod — before Mods were dressing like Mods – and told everybody to fuck off and shut up. Then the High Numbers came onstage and using instruments they borrowed from the other band, they started playing some Motown song at supersonic speed. Probably at that moment you could safely say the Who were the first punk band in the world – although they wouldn’t claim to be that, but they probably were, if you think about it. They got up and played a bunch of spade shit and Motown, and I remember saying, Wow, that sounds loud and obnoxious. Young, loud and snotty – but somebody else used that: Stiv Bators.

Yeah, the Dead Boys.

But these guys really were young, loud and snotty. But the Dead Boys did a Kim Fowley song once, called “Big City” – second album, Side One, Track Two (We Have Come For You Children, Sire 1978; actually it’s Side Two, Track Two). But anyway, here they were. They didn’t play “My Generation” that day; they hadn’t evolved to that level. But would I have recognized it? Probably! But I didn’t hear anything like that. I just heard some covers: “Detour” and some Motown songs or something.

But you were impressed?

Oh, yeah.

The same year you also saw the Yardbirds at the Crawdaddy Club.

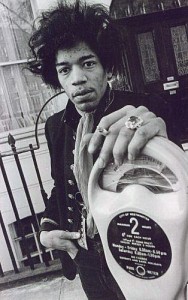

THE YARDBIRDS, 1964. “Eric told me that he wasn’t staying in the band because they were going pop and he was more interested in the blues.”

Remember, the whole time I was laying around Proby’s I still had the work ethic of a record producer. After all, when there was no dirty bitches coming around and no parties, you might as well go hear a band or do something musical. And so there was the opportunity. Somebody drove me over to the Richmond Athletic Club and the Crawdaddy. Kim Fowley does not drive a car. I’m car-phobic. I’m not interested in that. So all these adventures always happened on a bus or public transportation or hitchhiking, or people driving me around in their car or the back of a van. I think I’ve been in a limo less times than someone on welfare. I’m just a pedestrian, and it seems that to go in a car is really an event. Anyway, I got a ride out to Richmond Athletic Club on Sunday. I think it was matinee time, people underage who had to be at school the next morning. It was some afternoon concert and Giorgio Gomelsky was checking me out, and there they were: The Yardbirds. They were really good. I remember afterwards Eric Clapton came out into the line where I was standing and he said, “You’re really from America?”

I said, “Yeah.”

He asked me about the black music and the black records I knew – for example on “Alley Oop” by Hollywood Argyles it was an all black rhythm section. Before that, I’d worked for Alan Freed as a food runner and met Leonard Chess and I’d met Sonny Bono over at Specialty Records. I was a high school hustler and I had made black doo wop records anyway. I’d made several hundred records. Eric was very interested in black culture. He didn’t care about white punk too much.

Anyway, Eric was a really nice guy. I remember they went off to Eel Pie Island a week later and I went in their van, and Eric told me that he wasn’t staying in the band, because they were going pop and he was more interested in blues. That guy in 1964 was pretty focused on where he was determined to be. Whatever he is now, I believe he was anticipating that future event. He was a really serious guy.

Bill Relf, who was driving, was the father of Keith and Jane, who was the singer of Renaissance. I thought Jane was fuckable but I didn’t go for her because she was too clean. I don’t really go for clean girls and when I have I’ve failed. Keith was a good lead singer. They were really quite a great band, I think, and I became friends with them.

I was looking around to maybe give them some material, but I wasn’t really Billy Boy Arnold; I didn’t have that Chess Records pedigree as a writer. I wasn’t Willy Dixon. Nowadays I probably could’ve walked in and said, “Let’s do a shuffle, here’s some lyrics,” and I’d have dealt, basically. At the time I was not yet 25, still almost stilted by England, and it didn’t occur to me that I should be writing songs with my new friends the Yardbirds.

Who did we miss from ‘64?

Mickey Finn & the Bluemen. I found their record when I was running around London during the day while Proby was sleeping. I found that record at Oriole and I sent it to Chatahoochee who put it out (in the US). “I Still Want You” was the side I published. Have you heard that? (“Reelin’ And Rockin”/”I Still Want You” – Oriole CB1940, 6/64)

Yeah.

It’s a good record, isn’t it?

Yeah, it is.

And then the A-side was “Reelin’ and Rockin’,” a great version. I think that Mickey Finn & the Bluemen were better than Downliners Sect, full stop. Downliners Sect and the Undertakers had more publicity, but they never made any immortal records that I know of. We could argue about that but I don’t want to so we’ll continue on. (Laughs)

OK, how did your first trip to England end?

By then it was getting cold. It was November-December. It was cold and it was time to go home, so I went back to LA to Nick Venet’s ex-wife’s mother’s house, where I had lived before. I came back and knocked on her door.

“Can I have my old room back?”

“No, somebody else has it.”

So I called Danny Hutton up. I said, “Will your mother rent me the attic?”

“Yeah, we were looking for a guy, too.”

So I went up to the attic – Danny Hutton’s red attic – and Danny Hutton said, “Get some sleep because tomorrow night I’m gonna show you something that’s gonna be gigantic.”

“Yeah, Danny? (Skeptical) What are they called?”

He said, “The Byrds.”

THE MAGICAL BYRDS – EVERYBODY GOT LAID

By then it was the tail end of 1964, going into 1965; it was probably December. After the Christmas holidays it was time to meet the Byrds.

The Byrds at the time were ensconced in Clay Vito’s studio underneath his place on Laurel Avenue. He was this guy who – I don’t know how old he was, he might have been 60 or 70, or seemed to be. He had dirty bitches there and he fucked all of them and then everybody could fuck ‘em too, and then he had a dance troupe. The dance troupe would go around to all the clubs and dance. He had a practice room, and when they didn’t have sculpting classes that’s where the Byrds practiced.

Then their first gig was at what became Groundlings Theater, but then it was a ballet school, above the building where the Groundlings is now. There it was: the Byrds playing right out of Vito’s sculpting practice room, and all these actresses standing around and models and drug dealers and various refugees. They got up there, and they were magical. The fuckin’ Byrds! The original five guys with all those songs on the first album, one after the other, and Danny Hutton screaming, “Folk Rock! British Invasion! That’s it! That’s it!”

I said, “Wow, yeah. It’s good. It’s good! How do I fit into that?” I stood around and nobody cared. I was 25 by then. Jim McGuinn had been with Chad Mitchell and Bobby Darin, and one of the other guys had been with Les Baxter’s Balladeers. Everybody in the room had something to do with show business, so there was no opening to jump off of. There was no ‘moment’. I looked for it. I remember Danny Hutton said, “You had a #1 record last year! You can talk to a band.”

“Yeah, but there’s no fucking opening. Everybody’s around these guys like swarming bees. There’s no opening. Oh well, we can get laid, as guys in our 20s.”

Anyway, the Byrds couldn’t go back to the ballet place because they were fucking up the floor where the dancers danced. People were grinding their cigarette butts and dropping bottles and puking and whatnot. So Jim Dickson and Ed Tickner had somehow persuaded somebody at Ciro’s to let these guys come in. Ciro’s was losing their ass; maybe this could make it. So in come the Byrds, and it was glorious.

They did great nights. Those guys played every night. It was like the Liverpool Cavern, the Beatles in Liverpool, or Richmond Athletic Club when I went there and hung out with Giorgio Gomelsky and the Yardbirds.

By then the management company, which was called Tickson Music – Tickner and Dickson – had gotten them on Columbia so there was nothing to produce. The songs had been demoed to death. Everybody knew what the songs were. They were the same songs you hear on the first two or three albums; they were all in various shades of readiness. So as a result we just all got laid. Those guys, they attracted cunt and more cunt and super cunt, so everyone got laid, and… fine by me! I mean everybody.

Sonny and Cher went there and heard “All I Really Want to Do” and they covered it, and Phil Spector came there and studied it, and MFQ showed up, and later Phil Spector recorded with them. It was an interesting time in ‘65.

BLAME IT ON BOB DYLAN

Billy James, who wrote the liner notes of Mr Tambourine Man, took me to a Bob Dylan reception. That was where I asked him, “What’s your gimmick? What’s your schtick?”

And he said, “Asking questions and telling stories,” which was an interesting answer.

Then, the next night, Bryan Maclean and I were standing in front of Ciro’s.

“Hang on, let’s crash this party of Ben Shapiro’s” – who’s an agent – up the hill from where Ciro’s and the Hyatt House were. So we climbed over a fence and we decided we’d climb in through the kitchen window. I went first and couldn’t quite get over the stove, and a pair of hands dragged me across the stove – and it was Bob Dylan! (laughs) And then he grabbed Bryan Maclean and helped him through the window.

Then he said, “You guys want to have anything to eat?”

I said, “Sure, man!”

He said, “This is my party and I can’t stand the people in the other room. You guys wanna come? Hey, you’re that guy from yesterday!”

“Yeah, and this is Bryan Maclean.”

“I’m a Byrds roadie.”

“Cool. Have some chicken.” And he went and got us our food. He went and brought some plates into the kitchen and fed us both, and we sat there and talked to him, y’know, about nothing. Just chatting away. He was not happy with his own party. He was very kind.

Later, the next night was the night of the album picture where he’s standing with the Byrds (on the back cover of Mr Tambourine Man — MS). Then there was a party across the street and me and Danny Hutton went over there. We followed the entourage over and Dylan got lost from his entourage and ended up in a room at the hotel apartment building, and the people became a lynch mob:

“Sing for us or we’ll kick your ass! Fuck you!”

They were being mean to him. I felt bad for Bob Dylan, so I jumped up and said, “Fuck all of you. I’m better than he is and I also sing better in his voice! So you, Bob Dylan, play me Bob Dylan chords.” I got him off the hook, in other words.

So he said, “What do you wanna sing?”

I said, “I dunno, what have you got?”

He said, “Sing something about walls.”

So he played some Bob Dylan chords – the real Bob Dylan – and I got up in 1965 and sang [Dylan voice]: “Yeeeah, waaalls… Waaalls… Why the tears and pain?” and it sounded like him — especially with him playing I could really get some “Eeeeaaahhh” [imitates Dylan sound]. And of course the audience was shocked, because who’s this other guy? Why’s the real guy playing and the other guy imitating him singing, but the guy he’s imitating is playing guitar? (laughs) And it sort of shut everybody up. They didn’t know what to do. They didn’t want to fight, but they also didn’t want to applaud either. They were so confused they didn’t do anything to either one of us.

Then Dylan’s handlers came in and whisked him out, and he said, “Here! Have some wine!”

I don’t drink, but you drink if Bob Dylan offers you a flask. And he said, “You’re as good as I am!”

So for all of you who think I suck, blame him, because he told me I could sing as good as he could. If Bob Dylan thinks I’m as good as he is… For all the awful Kim Fowley records which have come out over the years, it’s all his fault!

HAVING A RAVE-UP IN THE HOLLYWOOD HILLS

As the summer got going, or somewhere before the summer, Giorgio Gomelsky paid me quite a bit of money to have a big publicity bash for the Yardbirds, where I got everybody that counted at Bob Markley’s house in the Hollywood Hills. (It was September 9, 1965. The Yardbirds didn’t have the necessary work permits to perform any real gigs on their first US visit, so the party was a ruse to expose the band to the LA hipster elite – MS) I conned him out of his house for the night, and we had Al Kooper and Riley Wildflower and other notables were the opening act for the Yardbirds. We staged a fake jewel robbery with actors and he had paste jewelry that was found. We had rooms where we had gambling and some poker. There were rooms where we had pinball and gambling and pokering and jewel robberies.

How did the jewel robbery happen?

Well, we said, “Somebody’s stolen jewelry! Get everybody out here!” [into the main room] That was just a trick to plunge the place in darkness while we were allegedly catching or fighting these jewel thieves. Meanwhile the Yardbirds were setting up in the darkness; we actually got them to set up in the dark! (Laughs) And if you can imagine starting off “I’m A Man” in the complete dark – how loud that was and how dark that was…. Rock’n’roll in the dark just really blasts! And then the lights go on, the jewels are there… and there’s the fuckin’ Yardbirds with just full Marshall amps, or whatever it was, doing “I’m A Man”! The place erupted and we had about two or three hundred people inside a big, big house. We had Phil Spector there. It was a great party. We wouldn’t let Brando in. Marlon Brando came with Natalie Wood, and Albert Grossman with Joan Baez, and they couldn’t get in.

There was no more room?

Right. That was fine with me because then I then intimidated all the 100 DJs to play the Yardbirds: “They can’t get in, you did, so you better play their record tomorrow!” That was gimmick we used to get airplay for 100 markets. Everybody showed up. There was a lot of people. DJs from all over the country came for that one. It was a remarkable evening. I made five grand that night, and that’s where the West Coast Pop Art guys first got together.

The Yardbirds

So this must be about the time that you hooked up with Michael Lloyd and the Rogues, right?

No, I had met Michael Lloyd in ‘63, before “Popsicles and Icicles,” when he was 13. He’s ten years younger than me: I’m 61, he’s 51. He was a teenage boy genius producer-engineer, and he could play anything. So I became friends with him because I had had hits and I saw that he had potential to be a producer, as well as an all-round musician. But I met him in ‘63. But in ‘65, that summer as the Byrds exploded, everyone who had a garage band had decided to be the Byrds, and his band became the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band, but he was more interested in girls really. (laughs)

I think I co-wrote two songs that later surfaced on a reissue by Sundazed: “Insanity” and… I can’t remember the other song. (“Don’t Let Anything!!! Stand in Your Way” on their self-released 1966 album – MS) And, yes, there’s three more albums in the Reprise vaults that are unreleased, because they only put out marginal or weird stuff, which is too bad because there was some really good albums there.

So Bob Markley basically controlled that group, even though he had no musical talent to speak of – is that true?

He was kind of like Dave Clark was in the Dave Clark Five. He had a law degree and he had a million dollars, so he paid for it. I was a co-writer on a few songs and those guys sang and played, and Markley had parties they played, and that was about it. They had a really good light show. The light show was later acquired by Jimi Hendrix and the Animals – but I’m getting ahead of myself.

A BUNCH OF PEOPLE MAKING STUPID RECORDS FOR STUPID REASONS

It was a great summer, 1965. What can you say? I mean, you got to fuck without a condom and the girls looked like movie stars and you made rock’n’roll records. Everybody who wanted to could make a record for $100 and could be #1 in the world — and why not? Just because you didn’t know the band… You just showed up and you did it and there was always a label who would put it out and everybody was waiting up and down the street.

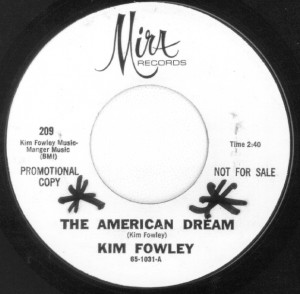

You made several singles of your won during this period. Tell me about “American Dream” for example. (“American Dream” b/w “The Statue” – Mira 209, 1965)

On Mira Records, with Sonny & Cher’s road band, the late, great Mike Henderson, who was an unadvertised Jack Nitszche, doing the arrangements. He was in Eddie Cochran’s band and he was one of the guys who played in the Marketts. It was done at H&R Recording Studio on Melrose, and came out on Mira Records, home of the Leaves’ “Hey Joe”.

What was the thinking behind the song itself?

I was God. I was living with a girl that had two kids, who was a Colgate/Palmolive model in Beverly Hills, and I saw myself the same way I saw myself in “Mr Responsibility”, which dated from the same period when I was coming out of the gutter and having sex with rich women who were slightly older than me, and living in mansions. (“Mr Responsibility”/”My Foolish Heart” – Living Legend 721, 1965).

On “American Dream” it sounds like you’re ready to take on the world or something.

You know, when you’re eternal, you have somebody else’s kids in the place of your kids and a Barbara Eden only better looking lookalike girl who everybody wanted to fuck on the street. On those two records, that’s how I saw my self-image at the time. Her name was Lois Johnson and she was also Bobby Jameson’s girlfriend, who was equally gutter-driven. He introduced me to her and I succeeded him as her boyfriend. There’s a recommendation! (laughs) God, the poor woman took on two morons in a row there!

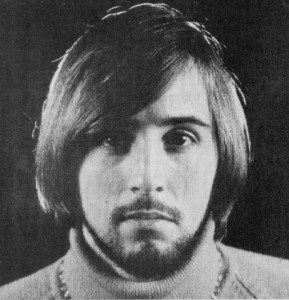

Bobby Jameson

So who played on “Mr Responsibility”?

That was the Mike Henderson guys again. Ben Benay — who died recently, but who had been on all the Grass Roots records — he played on that.

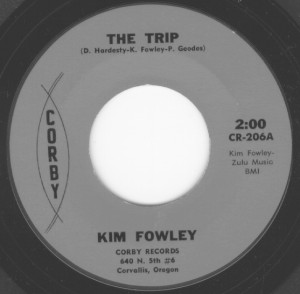

And then there’s “The Trip”. (“The Trip”/”Big Sur” – Corby 216, 1966)

I think I made “The Trip” first, when I was covered in slime, and then I washed myself off and made the other two records after that. But that single was made by a predatory guy who would fuck anything with a heartbeat. When Frank Zappa was out at the studio he used in Cucamonga where they did “Wipe Out”, there was another version of that studio, it was called S&L Recorders and I did a bunch of legendary stuff there. I did them as experimental fun records the same way that Frank did his experimental fun records out at Paul Buff’s. It’s a total Mexican neighborhood and you’re a white guy and you have pure white trash disgruntled middle class-to-rich kids all showing up together and being stupid and having fun. We wanted to make records like “Wooly Bully” and we wanted to make records like “Surfin’ Bird”, and we wanted the glory of a boxy drum sound and the glory of bad smelling people standing around and burping and farting and being… Nuggets. Very Nuggets. We didn’t know what Nuggets was because Nuggets didn’t exist, but what became Nuggets. All the records that were done, they’re on the two Dionysus albums — either that or the Creation reissue (Mondo Hollywood – Rev-ola/Creation CREVO36CD, 1995). Between those three releases in recent years you’ll hear them all. They’re all there in all their slimy beauty. It’s just a bunch of people making stupid records for stupid reasons.

So was “The Trip” just a backing track and then you did the words? Did you have any input on the track itself?

No. I walked in, they said, “We did a track but we don’t have a singer.” I said, “I’ll sing. Turn on the machine.” They turned on the tape, I made up words, and that was it.

Wow.

Paul Geddes was on it. We had [other] records, and a publisher/writer relationship on the second Surfaris album, with “Point Panic” on it, and the songs we wrote were “Hiawatha” and “Earthquake”. Then we had a publisher/songwriter relationship on the Aki Aleong & the Nobles’ record (Come Surf With Me – Vee Jay 1060, 1963), which is on Cowabunga! (Rhino Records’ surf boxset) – so that’s who those guys turned into. We recorded in and out of those conditions.

In the Doors’ Moonlight Drive book it says that in ’65, “The Trip” was on the jukebox at the London Fog [where the early Doors played – MS]. Jessie, the guy who was the bartender and the owner of the London Fog, he used to play that as the break song. But if you play “Soul Kitchen” and then you play “The Trip” by Kim Fowley you’ll hear the similarity. I’d never heard “Soul Kitchen” until the trailers for the movie in the ’90s. I was in the shower in a hotel in Orlando, Florida, and suddenly I hear “The Trip” with Jim Morrison’s voice singing some other words, and I ran out and I said, “Oh no!” – I had never heard Doors albums, I had only heard Doors singles. “Don’t tell me they stole the fucker back in ’65/’66!” So if it would have said “Morrison-Fowley” on there, life would’ve been a lot different than it is.

So was the band on “The Trip” the same outfit that you did “Underground Lady” with? (“Underground Lady”/”Pop Art ‘66” – Living Legend 725, 1966)

Yes.

So that was maybe six months later in early ‘66?

No, it was ‘65. “Underground Lady” was done the week that the Yardbirds came to town, because I played it to them and they said [unenthusiastically] “Oh… garage.”

They could dig the influence though, surely? [on the double-time rave-up parts]

Well, they didn’t think they were garage, they thought they were black. I was trying to be English and they thought they were trying to be black and we all kind of sounded the same. We were stupid people. (laughs)

LIKE THE TITANIC ON A RECORDING STUDIO FLOOR

On these records you were making in ’65 and ’66 in LA, you were comparing your state of mind to that of Zappa and what he was trying to do…