-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers -

Growing Up in the Dark Ages: The Early Years of Lester Bangs

By Mike Stax (with Gary Rachac)

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This story was written back in 1996. At the time there had been very little written about the life of Lester Bangs, and, being a San Diego native, I was particularly intrigued by his early years growing up in El Cajon (in San Diego’s East County) so began digging up what I could on the period of Lester’s life. My friend Gary Rachac had been close to Lester back then, and through him I was able to contact many of Lester’s other San Diego area friends and associates like Roger Anderson, Milton Wyatt, Jack Butler, and Jerry Raney. I also spoke to Richard Meltzer, who gave me his perspective on Lester and his work.

The story was originally intended for publication in the San Diego Reader, but when that didn’t pan out, I shelved it. When Jim DeRogatis began work on his Lester Bangs biography, Let It Blurt (published in 2000), I gave him permission to use the unpublished manuscript for his research. Much of it though appears here for the first time.

“WELL, I GUESS I’LL JUST GO BACK AND SELL SHOES IN SAN DIEGO!!!”

It’s early 1981 in New York City and Lester Bangs —writer, rock critic, ex-shoe salesman, and, for now at least, musician —is blasted out of his mind and far from pleased with the way his writer friends Richard Meltzer and Nick Tosches are responding to the advance tape of his new musical work, Jook Savages on the Brazos.

MELTZER: The last time I saw him in New York, he was at Nick’s house for a long time—a night leading into a day leading into an afternoon. He was just a mess. He says, “I don’t drink anymore.” He didn’t like the idea of ‘beverages,’ even cough syrup, so he was taking Ornical, which is an alternative to Romilar, it came out with a pill version. Two pills was a dose and a package contained 36. So he took 36 Ornicals and says, “Well, I guess I gotta wash it down with something. I don’t wanna wash it down with water. You got any whiskey?” So Nick gives him some scotch or something.

So he washes down 36 Ornicals with scotch. So he’s like both sedated and speeded up at the same time for like hours and hours and hours, and he’s playing the tapes of what I guess was the Jook Savages LP. Nick isn’t paying any attention at all, he’s just kinda giggling. He’d had enough of Lester already. It was just a period where we looked at each other and said, “Lester will be dead in two years.” Instead he was dead in… maybe it wasn’t even two years.

Lester Bangs died on April 30, 1982 of complications brought on by an overdose of Darvon (a potent flu medicine), ending a short and tumultuous life much of which was spent writing some of the most intense, funny, provocative, frustrating, enlightening and enlightened shit ever written about rock’n'roll. His doctrine was simple: “Rock’n'roll is by definition a deviant artform,” he wrote, “a bastard child, designed or destined to be completely unrespectable. It’s just a bunch of junk and shit, but it’s our junk and shit.” Maybe he didn’t respect rock’n'roll— why should he?—but Lester Bangs loved it and lived it, and what he left behind on the printed page was, sure as shit, as much rock’n'roll as any record you could care to name.

Seminal? Lester practically invented punk rock — or at least more or less coined the term way back in ’72 when he applied it to the crude, direct simplicity of ’60s garage bands like the Kingsmen and ? & the Mysterians, the minimalist experimentation of the Velvet Underground, and the raw power of Iggy & the Stooges, back when “musicians” and “rock critics” looked down on such low life forms as inherently “unmusical.”

But “seminal” isn’t the half of it. While, ostensibly, Lester wrote about bands and records, his best writing went deeper, telling his readers about his own troubled and often comic existence. “I’d say about a third of what he wrote was very much rubber stamp, business-as-usual, gotta-write-reviews-so-here-they-are,” reckons Richard Meltzer. As for the rest, much of it was brilliant, transcending the subject matter entirely and telling much about the way human beings relate to art and to one another. The best of it was written with a manic energy and fanatic conviction that was as close to the pure spirit of rock’n'roll as the music itself.

Appreciating Lester’s work, said Greil Marcus (fellow rock writer and editor of the essential Bangs collection Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung; Vintage, 1987) “demands from a reader … a willingness to accept that the best writer in America could write almost nothing but record reviews.”

For the San Diego reader it also demands a willingness to accept that the best writer in America could be a troubled kid from El Cajon.

* * * * * * *

As Interstate 8 curves east past the hills of La Mesa, the El Cajon valley appears; a flat, gridded tableaux of buildings, trees and billboards. The sudden Lost City panorama is almost impressive but that momentary impression soon dissolves as San Diego’s drab, suburban satellite stepsister comes into closer focus.

El Cajon has grown from a drab rural suburb into a drab modern suburb, but despite the proliferation of mega- and mini-malls and fast food franchises that have found a foothold here, the city’s basic character hasn’t changed much over the years. The mostly tidy streets of middle and lower middle class housing, the apartment units, the mom-and-pop shops, diners, churches and storage warehouses are much as they were twenty or thirty years ago.

Not far off the freeway on First and Madison is a small four-unit apartment building. There’s no plaque to commemorate this place’s significance, nor should there be, but up the painted red steps on the second floor is 463 First Avenue where, for several years, Lester Bangs lived, wrote and drank innumerable bottles of Romilar cough syrup.

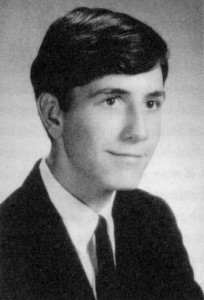

Lester Conway Bangs was born in Escondido on December 14, 1948. An only child, he moved with his mother, Norma, to El Cajon in 1959, a few years after his father’s death in a house fire. They lived in a series of apartments and houses around the El Cajon valley, supported by Norma’s jobs as a coffee shop waitress. By the early 1960s Lester was attending school at El Cajon Valley Junior High School and church at the Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall on Claydelle Street.

MELTZER: He had a totally miserable childhood, like everybody else—maybe more so than most. His mother was in her fifties or late forties when he was born. She tried to raise him as a Jehovah’s Witness and he couldn’t take it. He was a sensitive guy and all that and so I don’t think he was very well-armed by his environment to deal with anything. He had to invent himself.

Roger Anderson was one of Lester’s closest friends. He first met him during the summer of 1961.

ANDERSON: I was going into the seventh grade and he was going into eighth grade and we had a summer school class together called Creative Writing & Drama. He and I sort of hit it off during the course of the summer. He came over to my house to play once toward the end of the summer and my mother drove him back to his place. He told us he was excited about getting home because his mother was gonna buy him a stereo. She was supposed to have produced his first stereo by the time he got home that day.

And then the next year I was in seventh grade and he was in eighth grade, and my memory is that he snubbed me on the school grounds, I assume he didn’t feel it was appropriate to his social station to be hanging out with a little seventh grader.

Milton Wyatt was another early friend of Lester’s.

WYATT: We used to go to the same church; we were Jehovah’s Witnesses. His mother, Norma, used to have meetings over at her house, as Jehovah’s Witnesses do in the religion there, every Thursday evening. It was like a two-bedroom house with hardwood floors, not a slab —I say that ‘cos I’m into real estate now—it was a neat little house. He had his own room where he had his own record player and we listened to Charles Mingus and all kinds of other jazz people. He’d have all these jazz albums. I just couldn’t figure out how a kid his age [was into that]. I didn’t get it. I didn’t understand that he wasn’t with the normal thing. He was heavy into Charles Mingus. He’d play me these Charles Mingus albums and talk to me about bass and about jazz.

Lester was very opinionated about music. He would try to get you to understand why what you were listening to [at his house] was more important than what you liked. He would try to verbalize. He may have said, “What you like is a bunch of shit, but I’ll tell you why…” He’d always follow it up with some kind of reasoning and try to explain how the music was put together differently from the kind of music you were listening to. He made me understand some of it. But I liked what I liked.

ANDERSON: The year he went into high school, I was still in eighth grade, so we weren’t around each other, and I don’t think I had many thoughts about him. Then I was in high school along with him and I knew people who knew him. He was set up as the school’s main non-conformist. He was a fairly conspicuous figure and I was very attracted to him. I felt we had a lot in common, but I was intimidated by his reputation. Also he was a caustic sort of guy, which I didn’t experience first-hand, but I did sense that was the case, so I was sort of shy of making overtures that we would be friends or anything like that.

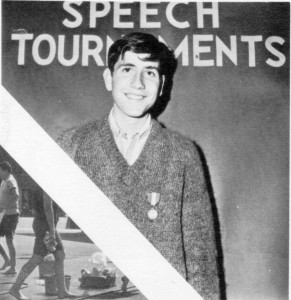

But then, as it happened, I was getting involved in Competitive Speech and he was involved in Competitive Speech. One of the central things through those years—a real hotbed for a lot of what he and some of the rest of us went through during high school—was this Tournament Speech class taught by Barbara Brooks, who was a young—she was 28 at the time—pretty, and very vivacious speech teacher. She had various speech classes and the central one was Tournament Speech where everybody who wanted to go to speech tournaments and work on speeches and be a part of the speech team and the debate team would all take this class. She was very easygoing and very encouraging and the speech class was filled with bohemian individualist types who generally weren’t into sports and weren’t thought of as being on the “A-list” of people in the high school social set. It was me and Lester and Rob Houghton, Randy Krause, Bill Swegles, and a lot of other people, and we had a wonderful time all through high school.

What would happen is we would go to that class and we would go through the formalities of being in class and then we were free to go out to wherever we wanted on campus to practice our speeches. So we would go out and do whatever we wanted: we would practice our speeches sometimes, but also we would just hang out and talk about sex and talk about music and act like idiots and have a wonderful time and argue about things. Lester had been doing it for a year and we were still being shy around each other — neither of us made reference to summer school or junior high.

Early in the term there was some kind of party at someone’s house for Tournament Speech people and Lester and I got talking there and he started telling me about how much he liked Bach. I assume this was in part because he knew I played the flute and was in the Band and Orchestra and all that stuff. I took it that he was being receptive. So we talked about that and he invited me to come by his place to listen to records some time. So a few days after that I went to his place and I remember a couple of things about that: one is that he loaned me his copy of The Subterraneans by Jack Kerouac. And also that we listened to this Chico Hamilton Quintet record which was in the picture for years after that. He always had that in his collection and sometimes I had a copy of it. It was the Chico Hamilton Quintet with Charles Lloyd playing saxophone and flute. Gabor Szabo was also in the combo and there was this long track called “Lady Gabor” or something. It was this thing where he’s playing flute and it’s very cool and very nice and it goes on for quite a long time. It got up to this part where it got to this climax where everything dies down for a second. The flute plays a flutter-tone and then suddenly crescendos up to this exciting surge of music, and just then there was an earthquake! We were sitting there listening to this on his turntable and all of our attention was on it. Suddenly as it was going into this crescendo everything in the room starts to shake, and it shook more, and then it sort of died away. We were both going, “Wow! This is really weird!” It wasn’t a serious earthquake; it just sort of came and went, but we always remembered and the rest of the time we knew each other we would occasionally make reference to that.

From that time on we were good friends.

Another early friend was Jerry Raney (much later of the Beat Farmers), who remembers Lester’s non-conformist streak vividly.

RANEY: The first time I met Lester I had just moved to El Cajon between seventh and eighth grades. My mom and our family had been going to the Jehovah’s Witness Church, and Lester’s mom was a total fanatic about the religion. We had just moved to town, and we got taken over to the Kingdom Hall Jehovah’s Witnesses in El Cajon, and there I was introduced to Lester, because “Here’s another guy Lester’s age.” He was this tall, lanky guy that looked like Abraham Lincoln without a beard.

We had gym classes together when we went to El Cajon Valley High School. He was always basically kinda uncoordinated—tall and lanky and kinda gawky. He didn’t appreciate playing gym, and he didn’t appreciate the coach’s attitude, Coach Foster. He’d miss almost every day, basically. It got to the point where it had been going for awhile where Lester didn’t wanna suit-up or he’d just stand there with his clothes on while everybody else played the games and stuff and did the regular gym class thing. He wasn’t into it at all.

So what happened, if you missed a day you’d lose 10 points and so to not get an “F” for that day you’d have to write a page per point on a sporting event. So the last time I saw Lester in gym class, he had missed a bunch of days and he came up to me before the class and said, “Well, I’ll probably be seeing you later. Here’s what I’m handing in to Coach Foster.” He handed me this big old long story, page after page, on “Hector the Homosexual Monkey.” I read a little bit of it and I said, “You’re not handing this in. This is a joke, right?” He goes, “No, I’m handing it in for my make up stuff,” and he shook his head up and down like he always did, nodding his head and giving you kind of a toothless smile.

He handed that over to Mr Macho Coach Foster, and after that Lester was just out of gym class!

ANDERSON: He was always drawing attention to himself. He got into trouble once at school because we’d line up outside the cafeteria to go up to these vending windows where a woman inside would sell you various food items. The vice-principal’s wife worked there, and Lester got suspended because he was in line there once and he got to the front and she said, “What will you have?” And he said, “Give me an O.J., baby!” (laughs)

You can tell how times have changed because now that would hardly even excite any notice, but he got thrown out of school for two or three days!

Jack Butler was another of Lester’s friends at El Cajon Valley High School.

BUTLER: He was always so intellectual, the teachers would be afraid of him. I remember distinctly him passing around copies of Naked Lunch and I got busted for reading it in Biology class. We had a major witch for a teacher and she just tore me a new orifice. It was pretty gnarly. It was pretty amazing reading that. I couldn’t believe that anybody would have a book that intense at that time. I could tell there was a little literary content in there, even though I was kinda reading it for the “good parts” — which Lester might have almost been doing himself at that age—but every sentence was a good part, y’know.

One of my earliest drug experiences that I can remember was driving around with Lester and having him take a quick spin through Jack in the Box to get a couple of chocolate shakes. I told him I didn’t really want a chocolate shake, and he said, “Trust me on this,” or something like that. He pulled out this big thing of nutmeg and just started lacing them heavily with nutmeg powder. I just thought he was out of his mind. He said he’d chopped it or ground it himself. He says, “Put this in your malt and you’ll get high.” So we drank our malts and he got pretty bug-eyed. I can’t remember whether I got high, but I definitely felt weird—but then you always felt weird hangin’ out with Lester! You always felt a little bit on the edge of reality. His energy was so high all the time and he’d pick you up and take you along.

ANDERSON: From the very beginning, there was that copy of The Subterraneans, and I’m not sure what order it all happened in, but The Subterraneans, On the Road, both by Kerouac, Howl by Allen Ginsberg and Naked Lunch by William Burroughs. He had me reading all of those in almost no time. As soon as we started being friends he was touting these things to me and he was loaning me his copies. I was totally blown away. This was my whole thing; this was everything to me. And he was writing this crazy poetry and stuff, and I was writing. I was going through long periods when I was writing a poem every day. We would show each other the stuff we were working on, and once I showed him something. I gave it to him early in the day and I saw him later and I said, “Well, what did you think of that poem?” And he said, “Oh it was just a stupid imitation of Ginsberg so I threw it away.”

He would do stuff like that. From this perspective I imagine he misplaced it or maybe he was just being ornery. I don’t know, but that sort of thing would be difficult to take sometimes. He would occasionally be hostile gratuitously but we would always get through it somehow.

Along with his literary pursuits, Lester’s music tastes were also evolving rapidly. The arrival of the so-called British Invasion in 1964 triggered some new obsessive directions.

ANDERSON: For the first year, I was a sophomore and he was a junior and that was the same year the Beatles broke and then the Stones and all of those bands. I guess he was alright about the Beatles, but he was totally nuts about the Stones. He went around for days with a picture of the Stones he’d cut out of some teen magazine pinned to his shirt as though it was a button. At the beginning of class one day, he asked Barbara Brooks if she’d ever heard of the Rolling Stones, and of course she said no, and he said, “They’re wonderful!” He was on this whole mission on just how great the Rolling Stones were.

WYATT: One time I went over there and it was like a light switch. He was playing this new thing he’d heard and he liked. It was the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me,” and the lead guitar in that was kind of furious and weird and strange. By today’s standards it was pretty primitive, and, God, he loved it! He was just rantin’ and ravin’ about that. I think he always liked the jazz thing, but from then on — and that must’ve been 1964 or ’65 —he liked rock’n'roll. I absolutely remember that because I would go over there weekly and it was jazz this and jazz that, and I would bring over my records of pre-Beatles stuff and all that and he would dismiss it—it didn’t have any depth or any meaning. And then he would play his stuff. Then all of a sudden that one guitar solo—which by today’s standards wasn’t put together well but had so much feeling and soul—from then on it was like this was it.

ANDERSON: From a real early point in our friendship, all this rock’n'roll stuff was a huge thing for him, but he listened to everything. He really did know classical music, and he listened to jazz. He knew jazz extremely well and he was really big on Charles Mingus. Charles Mingus was just about the biggest thing for him all during high school. He was also big on Bob Dylan. He was huge on Bob Dylan. Gigantic. There was no overestimating how big Bob Dylan was for him. This was before “Like A Rolling Stone.” He had all the early albums and one of the albums he loaned to me a lot was Bringin’ It All Back Home.

And he was also into East Indian music before the Beatles and the other bands were doing all that stuff with sitars—this was before any of that! I would go over to his place and he would put on sitar music and he would talk about raga. He wrote these poems called “Ghost Ragas,” a series of them.

Most of this cultural stuff he got from Ben Catching, his nephew—the Beats and then the jazz and the Indian music. For all of it, the major influence was Ben. Ben must have been around 20 by then and he’d been feeding Lester these books, stuff like Henry Miller even before the Beats and then the Beats. He’d been passing this along to Lester since he was in junior high, and by the time I came along Lester had assimilated all of it. It was his main preoccupation.

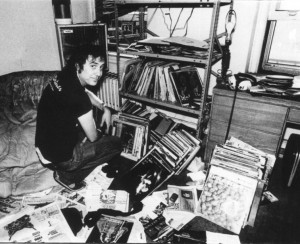

Lester devoured all the offbeat literature and music he could lay his hands on. “My most memorable childhood fantasy,” he later wrote, “was to have a mansion with catacombs underneath containing, alphabetized in endless winding dimly-lit musty rows, every album ever released.”

He fed his vinyl addiction with regular bus trips to Ratner’s Records in downtown San Diego where they carried a wider selection of obscurities than was available anywhere in El Cajon. At Ratner’s, Lester would paw through the bins looking for the wildest and most out-there looking jazz and rock’n'roll albums and then ask the lady behind the counter if she’d play them for him. “I’d listen to about 16 seconds of clamor and say ‘I’ll take it’ while everybody in the place snickered,” he wrote.

More vinyl came in from mail order record clubs which Lester would sign up for indiscriminately, taking advantage of the cheap and free records they offered but refusing to fulfill his obligations to buy the designated number of records per year. “He had record clubs all over the country coming down on him,” remembers Roger Anderson. “They finally took him to court. I forget what happened. It might have got dropped because everyone lost interest at the last minute, or he might have had his wrist slapped.”

Lester found something of a kindred spirit in a pretty red-headed girl a year younger than him: Andrea DiGugglieli. Lester and Andi had an on-again/off-again boyfriend-girlfriend relationship that lasted through high school and beyond.

WYATT: She was neat and strange all at the same time. I think he really liked her for a long time, and when he finally went to Detroit and New York and all that I think it bothered him that they weren’t together. She was tall and thin with sort of longish hair and she would definitely be his little poetry bud. They did their little thing. When I lived on Claydelle, I think he and Andi came over and they were on Romilar. At one point Romilar cough syrup was a big deal there for awhile.

ANDERSON: Andi was a big, strapping, good looking Italian-American girl. Very, very smart. Even when he went off to live in Detroit and work on Creem magazine, after we got out of high school, he would come back two or three times a year and always spend a lot of time with her and spend a lot of money on her. He would always buy her a dress when he was in town.

They started going out, I think, the first year Lester and I were friends, and then they were together all the way through high school and then after—there was never a definitive parting of the ways. He also had other girls he was involved with sort of in-between, so I guess maybe he and Andi would break up occasionally. It was one of those things where they were joined at the hip whether they wanted to be or not. They were real simpatico even though they were always fighting. They were both eccentric. They both got a big kick out of rubbing the fact that they were different in everybody’s face. At the time, the Carnaby Street thing was big and Andi would wear this outfit which included a little deerstalker’s cap and a kind of cape. During lunch hour, Lester would take the deerstalker cap and the cape and he would go around wearing it. People found it very threatening and very annoying, and they would look at him funny and mutter to themselves, but he just loved doing that.

As close as Lester and Andi were during high school, like his heroes the Rolling Stones, Lester couldn’t get no satisfaction. So, as Roger Anderson remembers it, in his senior year “Lester got this jock friend of ours from the speech squad to take him down to Tijuana to get some experience…”

ANDERSON: He went off to Mexico, slept with a prostitute, and got the clap. He went to a doctor for treatments and everything was OK, but somehow word of the whole sorry episode got back to the Kingdom Hall where his mother was a congregant and where Lester, even though he hadn’t attended a service in God knows how long, was still considered one of the brethren.

Exactly how everything went down is still a matter of conjecture, but, coincidentally, as tongues around the valley were wagging covertly about his Mexican misdeed, Lester was due to speak before his “brothers” at the Kingdom Hall. The shit was about to well and truly hit the fan…

WYATT: I may have been 16 and he was 17, I think. What a heavy deal. There’s a thing in the church that on Friday we would go to this thing for two hours. We would go to two different meetings for an hour each, and one would be that certain people would be given an assignment to do: a five minute speech, or a ten minute speech, fifteen, twenty, and it all added up to an hour. It depended on your age, they would start with the little ones and go up to the bigger ones who were more secure in doing it.

So Lester was up there doing his speech, and all of a sudden he just let ‘em have it. He was angry. He’d started his ten minute speech—they’d give you a subject and they’d give you certain chapters to research—and he was probably about a minute or two into it and… that was it. All of a sudden: “This is garbage. This is bullshit. I can’t do this…” I’m not quoting ‘cos it was so long ago, but I remember it being something like, “You’re a bunch of hypocrites. You say this and do that.” I remember the word hypocrites a couple of times at least maybe, and he may have said the f-word.

Being there, it was like a scene in Hell had opened up. People couldn’t move for about a minute until somebody probably walked up there and said, “We’re not gonna have any more of this. You can leave.” I can even remember which side of the aisle he walked down; he came right past me. He just walked out. I don’t know how he got home or where he went or what. It was pretty dramatic.

Anyway, he never showed up again and they never went over to his house again. I think they moved the meeting from his house on Leslie Street. Eventually I think he was determined “disfellowshipped,” which means you can’t even talk to him. If you talk to him it means you’re talking to the devil or something. But I did. I actually left myself a couple of years later, but not in such an outgoing fashion as that.

ANDERSON: Lester told me that the Jehovah’s Witness people had asked him to come in because they were gonna talk to him with a view to excommunicating him— or whatever their term for it is. So I met him over at his mom’s garden apartment in the middle of El Cajon. As we were walking down to the Kingdom Hall, which was a few blocks away, he saw a pair of those paper sunglasses they give you at the optometrist shop after they dilate your pupils; they were all torn. So he picked those up off the street and he put those on and he lit a cigarette and we walked down to the Kingdom Hall.

The people who were gonna talk to him were waiting there for him. They didn’t want me to come in because they said it wasn’t a matter for someone who wasn’t a member, and Lester argued with them about it. He said that I was his friend and that he wanted to have me there and all the rest of this. But they prevailed. They weren’t bad at all; they were very reasonable. They weren’t being pushy and they weren’t trying to bully him, none of that stuff. So they prevailed about me not going in.

They all went in and I could hear a lot of it from outside. They were asking him about his interests and his beliefs, and I just remember that they asked him if he believed in God and he said that he believed in other things like travel and poetry and music. That’s about all I remember from the conversation I overheard. It went on for awhile and then it was over with and he came out and we went back to his place and probably listened to records and read comic books.

The Jehovah’s Witness incident was a big step in Lester’s self-development. Not only was it an assertion of his individuality and his disrespect for authority, but also a dramatic public rejection of the belief system of his family. But as Roger Anderson was later to realize, Lester’s brash, rebellious stance actually masked a sensitive interior that was racked with insecurities and self-doubt.

ANDERSON: He had seemed very nonchalant about it, like, “Oh, hey, they want me down at this thing. Do you wanna come?” He didn’t act like “Do this for me as a friend” or “I’m in need of support” or all the rest of that stuff. He was just acting like he could give a shit. It wasn’t until a long time later that I was thinking about it and I realized that he was sorta scared. He wasn’t a big, scary adult; he was just a boy: a teenager. He was as rebellious as all get-out, but this was scary for him and he basically, I imagine, asked me along because he felt like he needed a friend nearby as he was going through all this, which is why he argued with them about whether or not I could sit in on their meeting.

RANEY: He got kicked out of the church—so that was the second thing I saw him get kicked out of! But he was still in high school and we’d still run into each other and talk a lot, especially when the Yardbirds came out. He went totally berserk when the Yardbirds came out. He just wouldn’t let up on the Yardbirds! We’d talked about music a little bit before but he wasn’t that into it. He was into it, but not like he was when the Yardbirds came out. He totally started frothing at the mouth!

I remember one day meeting him on the street in El Cajon and saying, “What have you been doing?” And he says, “I’ve been listening to this band the Yardbirds. Boy, they’re really great! Jeff Beck is the best lead guitarist around.” At that point I’d only heard their hit on the radio, “For Your Love,” and there weren’t any searing leads on that record. He was talking to me about guitar players ‘cos he knew I played guitar and that I’d been playing for six months or something like that. He was saying, “This Jeff Beck guy’s really good,” and I’m saying, “Well, he can’t be any better than Lonnie Mack!” I was just thinking about technical guitar players, but Lester was talking about lead guitar playing as an art. It took me a little while to figure that out, and once I did figure that out, that’s when we had Thee Dark Ages. We started playing all these Yardbirds songs and Animals songs and everybody.

That’s when Lester used to come up with his harmonica and I would introduce him as “The Best Harmonica Player in San Diego County” or something. I thought he was pretty creative on the thing. We’d bring him up to jam and we’d play an extended version of “I’m A Man” or something Yardbirds style and just go on this big psychedelic jam. It was quite cool. He used to always dig getting up and jamming with the band.

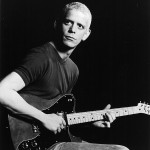

Lester’s friend from Biology class, Jack Butler, was the bass player for Thee Dark Ages…

BUTLER: We were kinda the long hair band. Back in those days there were long hair bands and there were soul bands. We were doing the English Invasion stuff and some of the American stuff that sounded like that, like some Paul Revere & the Raiders stuff.

WYATT: I heard Lester play with Thee Dark Ages. I still have a matchbook they had. I’d go see them at the bowling alley, which was the Hi Ho Club. It was great. I have great memories of that. I always wanted to be their drummer. I was probably second or third out from being their drummer, but always considered myself a wannabe-second out. At the time they had a guy named Bob. His father owned a magic store in a Unimart shopping strip in El Cajon. It was like the shopping plaza at the time, and he owned a magic store, card game, all-around-store thing and they used to practice in the back.

BUTLER: We had Bob Friedman on drums, who wasn’t really a rocker but who was cool, and then we had Chuck Surface, an incredible organ player, and myself on bass, and Jerry on guitar. So we had a four-piece band, which was conducive at the time to doing this English stuff. Also we would bring out featured singers that the house would hire at the Hi Ho Club, which is now next door to Park Place. The room with the stage where we played is now movie theaters. It’s funny because it was a plush place. It used to be called Art’s Roaring 20s. It was really nice: thick velvet carpets, like the Roaring 20s after the Untouchables’ motif. It had bombed as an adult night club, so they opened it as this teen club and there were huge lines around the block.

We had to join the union. Of course Lester didn’t—he was the featured sit-in guy and the management probably didn’t even know he was up there. But we had to join the union, just as high school kids, and we had to actually sign contracts for full union scale and kick back a large percentage of that to the management. They were paying us something really low, probably 30 bucks a night max, and union scale was probably twice that. But we had a solid three nights a week job for a long time, and we were high school kids, actually making money playing the music, basically, that we wanted to do. Pretty amazing.

ANDERSON: Lester wanted to be a musician. He went and took saxophone lessons when he was in high school or junior high school. I wasn’t aware about it at the time, but he told me about it years later. Even in Thee Dark Ages he was totally into jazz because he was serious about jazz even up into his Rolling Stones period. He was totally into rock’n'roll in just about every way but still in a lot of ways jazz was his first love. He wanted to be a jazz musician in the worst way, but apparently couldn’t apply himself to it.

I never saw him play with Thee Dark Ages. I was out of the picture at that point. That would’ve been his first year out of high school and I was going through my senior year in high school and there was a period of a few months when we didn’t see that much of each other.

BUTLER: Sometimes Lester would come up. Jerry wasn’t really as into people sitting in as much as I was, but Lester was a special case. He’d come up and basically kind of make noise. It was high energy noise and it was cool. He’d do “I’m A Man” and “I Wish You Would” and “I Ain’t Got You”—mostly Yardbirds kind of stuff. We were all really into the Yardbirds at that time—the rave-up stuff. I loved it ‘cos I loved that Yardbirds bass style, walking up real high and doing all that weird stuff. It was a lot of fun to play bass on and it was real cool to have harp as an extra instrument, so every time I saw Lester I’d try to get him up on stage, and he’d usually come up; he’d always want to. It depended on how many managers were in the room and how many chances the band wanted to take with cacophony onstage. He got pretty gnarly.

Lester wrote a little about his experiences with Thee Dark Ages in some untitled notes published posthumously in the Psychotic Reactions And Carburetor Dung collection:

When I was in a teen band playing the local bowling alley in 1966 I got to blow harp on four or five songs every night: “Goin’ Down to Louisiana,” “Blues Jam,” “I’m A Man,” “Psychotic Reaction” and I forget, and I noticed at the time that these guys just LOVED to play “I’m A Man” and pretend they were Jeff Beck, but they always groaned when we had to run through “Psychotic Reaction,” and while I had no technical knowledge of music it did seem like they came awfully close to being THE SAME SONG. (Okay, throw in a little “Secret Agent Man” on “Psychotic Reaction.”) I played harp exactly the same in both. But it was understood that “I’m A Man” was the admittedly almighty Yardbirds, or (if these guys were that hip) the unquestionably authentic and righteous bluesbustin’ dad of rock’n'roll Bo Diddley — but who the fuck were Count Five? Just a bunch of zitfarms from San Jose about like the band I was in, that’s who, so fuck ‘em. Which of course meant that my fellow bandmembers considered themselves worthless, but I never bothered to bring this up.

After graduating from high school in 1966, Lester attended classes at Grossmont College (he later went to SDSU for a year or so). Still living with his mother, by now at the apartment on First Avenue, he earned money for awhile as a dishwasher—a job he scored through Norma’s contacts as a waitress—until Ben Catching found him a more permanent position at his own place of employment: Streicher’s Shoes in Mission Valley. The job as women’s shoe salesman lasted for several years, but Lester’s musical and literary ambitions and thirst for the wild life never took a back seat. He was always looking for new initiates, and found one in 14 year old Gary Rachac…

RACHAC: My first recollection of the name Lester Bangs was during the great handball scare of the late sixties. We would routinely on weeknights go play handball at the courts across from Lester’s apartment. One night I was standing on the street waiting for my dad to pick me up and a guy came up with an arm full of records and said, “Do you know if Lester Bangs lives around here?” I’d never heard the name before but it stuck with me and for some reason I had a general idea where he did live, and I just pointed and said, “Yeah, I think it’s over there…”

The very first time I ever got together with him was probably about six months later. It was the day I first heard the first Velvet Underground album and it was in an apartment building near the Hi Ho Club. Tim Andresen, Roger Anderson and I went over to Lester’s house and picked him up and drove over to Tim’s house. We did silly things like hyperventilated. There used to be a craze amongst school kids 12 and under where you’d hyperventilate, then hold your breath and you’d pass out for 30 seconds. We were doing that sort of thing there. I really didn’t see much fun in it, but, hey, Lester was doing it, so I thought it must be cool.

To look at Lester, back then, you wouldn’t think he was a rock’n'roller. He was a very preppy-looking individual. I looked at him and I remember thinking he looked like my study hall teacher, but as soon as he opened his mouth I knew I was in the presence of royalty. He was so animated about everything he would say. I was about 14 and Lester was about 19, but despite my lack of age I had a rather illustrious concert going career in San Diego and that impressed Lester. I was lucky, ‘cos I had been caught in that first wave of the British Invasion and that rock’n'roll of the mid-60s. I hung around with one of the DJ’s sons, who was one of my best friends when I was a kid, and consequently we got into a lot of shows. I’d seen the Stones when they first came in 1964 and he didn’t see the Stones until ’66 at the Civic Theater. He had heard about me through Roger and Tim Andresen. After that, his house had become somewhat of a magnet for that little circle. His mother was really never at home. He was so close to the school that we would very routinely go over to his house after school every day.

The first time I went over there he had a Gentrys album on the box and a Sam the Sham record there, and that kind of blew it out of the water for me. I’d heard from Raney that Lester had turned him onto the Yardbirds and shit. It kind of perplexed me; I couldn’t figure him out. But he was the kind of guy who just wanted to hear everything, y’know? He and I were always going buckle to buckle between the Stones and the Beatles. He had valid points that he made. For example, he always held it against me that McCartney did “‘Til There Was You” on Sullivan. I was defenseless. I had nothing to say. He would say, “Rachac, they believe in this shit!” And I was like, “What can I say? They’ve progressed since that point.” It was kind of a push and pull there. Lester loved the Stones, but I can’t remember him ever going to bat for the Beatles. But that wasn’t his place in the world. He wasn’t there to champion the icons, he was there for the underdog.

I can remember him reading Howl, and we were drinking a bottle of wine and listening to John Coltrane. These were kinda scary elements for a “pop” kid. I was pushing the bounds there as far as my cultural appreciation for the time. I can also remember smoking pot with him at his mother’s apartment, in his room. I’m sure she knew something was going on. She was very stoic.

According to all accounts, the house was fastidiously clean and orderly with the exception of Lester’s bedroom which was a complete disaster area, strewn with records, books, comics (Uncle Scrooge was a big favorite) and magazines.

RACHAC: There was one time I went over and his mother had done him wrong by cleaning his room. Lester had been at college that day. Of course, Lester couldn’t find anything, it was so completely organized. So he said, “Do you want to help me get organized?” I couldn’t understand what he meant, but he gave me a pile of records and I stood there, and he picked up another pile and started spewing them across the room. I caught onto that and I started throwing things helter skelter. And then we did that with his books. His mother had picked up his skin mags and put them in nice piles! He was a great porn connection at the time. He was worth his weight in gold at that point, even more so than the vinyl! “Hey, Rachac! You want some stroke mags? Here! I’m through with these.”

My first public drunk was with Lester at Larry Dykes’ house on Claydelle Street in El Cajon. I must’ve been 15 and he was old enough to buy. We went up to the Mayfair and he bought a bottle of Spanish Rose. We took it back there and drank it. That was my first and last bottle of Spanish Rose! Up until that time it was, I think, Contac. He’d take that and pull the Belladonna out of it. It was a capsule cold thing anyway. I know Romilar was a big favorite of his. I did drink Romilar once but it was too much like medicine than what I had in mind. He’d just drink it like soda pop, a whole bottle or two.

Lester and his mother were definitely the odd couple. Norma the meek, polite, hard-working waitress; the devout, church-going Jehovah’s Witness; and Lester, the obsessive bohemian, swilling booze and Romilar and gulping down absurd cocktails of legal and illegal medicine, always in search of the new kick, the new sound, the new high, the new experience. His mother evidently had no control over her son’s rebellious behavior, and the absence of a father figure would have had to have something to do with this. Though Lester must have felt the loss of his father deeply, especially considering the tragic circumstances of his death, the subject rarely came up.

ANDERSON: Lester would mention his father sometimes. He talked about going with him up to LA and looking at the smoggy sky and how beautiful it was. See, we were into finding beauty in unprepossessing material. We liked smoggy skies and all this atmospheric film noir-type stuff. I don’t remember anything he said that his father said or did, just that he took him to LA for some reason, and his feeling of joy seeing the smoggy skies.

Lester smoked at home, even when he was in high school. I’d go over there and visit him and his mother would be there and he’d be smoking. I remember her remonstrating with him because she thought he was being careless with a cigarette, because that was how his father died. His father, I think, died because he fell asleep with a cigarette, and she told him, “That’s what happened to your father.” And Lester just ignored his mother until she was blue in the face. He had no use for her. I came to realize years later that he actually loved her very much and was very attached to her, but he never showed it. He showed it maybe once in the whole time I was around the two of them. But the general rule was that he went contrary to her wishes and refused to adopt any of her values, and would get money out of her and use it to buy drugs and alcohol and stuff. She couldn’t discipline him at all. She wasn’t like him at all. She was a very sweet woman.

She hated me. My mother hated Lester and Lester’s mother hated me, because my mother thought Lester was the bad guy and Lester’s mother thought I was the bad guy—which I always thought was a laugh because Lester was the one who introduced me to all this stuff! She was very sweet and very quiet. I think she was smart enough where she didn’t have any of Lester’s qualities—none of the enterprising, thinking, none of the interest in strange new things. None of that. She really was a nice Jehovah’s Witness lady and she was always wanting him to be good and fretting over things he did she thought were dangerous. But she never put her foot down. She didn’t even raise her voice to him. She just pleaded with him to try and exercise some restraint, some judgment.

Lester’s mother would die just a few weeks before he did.

WYATT: It was good in a way that she died first because [Lester's death] would’ve probably broke her heart. She really loved him. His mom and my mom were pretty darn good friends and she would come over all the time and she’d always talk about him. I tell you, he had a best friend in her. I’m sure she did a lot for him. Anything she could probably give him… It was meager, she didn’t have a lot, but I remember that car, they had a Mercury which was real stylish at the time. She was proud of that.

ANDERSON: In early ’68 I remember he’d come up with this brilliant thing: The best way to steal records out of drug stores. He would go into these places and steal a couple of bottles of Romilar and then he would grab some records and just walk out of the store with them. He was so proud of himself: “None of that sneakin’ around! Just grab ‘em and walk right out.” So he and Jim Bovey and I went out driving around, and went to the Long’s Drugs or whatever it was, right there on Main in El Cajon. He stole a bunch of records and he got a couple of bottles of Romilar and came back out to the car. As we were driving around he drank two bottles of Romilar.

Then we went up to the White Front store that’s out there towards La Mesa. He went in, and he was in there for a long time. Bovey and I were starting to worry, and finally we went in to see what was going on. As we were walking towards the entrance, here comes Lester backed by two cops who were taking him to a cop car. So we just walked by. He didn’t acknowledge us and we didn’t acknowledge him.

He was only about 19 at the time, and they took him to jail or whatever. We were back at my parents’ place going, “Jeez, this is a bummer. What’s going to happen?” Then my father gets this call. I forget exactly how this happened, but in essence Lester had given the police my father’s name as the adult to come and pick him up! Lester really liked my parents because they were nice people and they had liberal leanings and all this stuff. My father liked jazz and stuff and Lester’s father died when he was quite young and that was a big thing for him. He really missed his father and so he had all these feelings for both my parents.

And so off my father went, being essentially a very good-hearted man, and we’re back at my house going, “Is Lester even going to be able to act like a human being?” ‘Cos he’d drank two bottle of Romilar! We couldn’t believe that they were even letting him go.

Then, 40 minutes later, here comes my father. He’d taken that old blue ’49 Ford that he’d had for years, and there’s Lester sitting in the passenger seat, smiling at us like he’d gotten away with it. My father just pretty much kept his nose out of the whole thing and didn’t want to enquire as to what was really going on. He wasn’t really interested in whether he was on drugs or anything like that. Just went and picked him up and that was it, signed for him.

Later he had to go to court, and he got one of his teachers at Grossmont College to be the adult, ‘cos he was basically being charged as a juvenile, I think, ‘cos he was only 19 and he didn’t have a record. I don’t know how, but he got off the hook without ever having to appear. Him and this guy showed up at the court, and before they ever went in word came out that the whole thing had been dropped.

By the summer of 1968, Lester was earning enough from his Streicher’s job to move out of his mother’s place and into a house with Jack Butler and some other rock’n'roll types. The house was on what was called Tobacco Road, a now demolished cul-de-sac on the north side of Broadway in El Cajon.

ANDERSON: All those Tobacco Road houses were houses that were up on blocks. I mean, they weren’t even real houses. It wasn’t like they were houses with foundations. It was one of those things that they were in some kind of transitional state. Probably nothing was up to code or anything like that, so it was all very tenuous anyway.

I was over there a lot. I was too stupid to think it was depressing. I was too new to the whole thing. I was still living at home with my parents until some years after that. It was cool in a lot of ways. We’d go over there and get high—by that time we were all getting high. With Lester it had started years earlier, at least occasionally smoking pot. For me it started in ’67 when he gave me some Dexedrine pills and then we all started to smoke pot. It wasn’t just occasionally. You’d always have “a lid” or you were talking about how you needed to get “a lid.”

BUTLER: I can remember sitting around spending a lot of time with headphones on, totally spaced out, listening to weird music with Lester. He’d listen to Coltrane and Beefheart and I’d listen to Are You Experienced and Axis Bold As Love. In general, that was the difference in taste. Like I’d listen to Fresh Cream and he’d listen to Psychotic Reaction. But he’d get stoned enough to like anything. That was before he’d got as jaded as he became later, as far as commercial rock, when Hendrix and Cream were still on their way up.

ANDERSON: Lester ascribed to a lot of ideas that later he was in complete opposition to. In ’66 and ’67 he wanted rock’n'roll to be “art.” He didn’t want rock’n'roll to be inarticulate and stupid. He found all that to be anathema and he was a real snob in a lot of ways. The thing is, no one was really talking like that at that point. It had just gotten started so it wasn’t like he was falling in line with anybody else’s ideas. He wanted stuff to be artistic and sensitive and well-worked out and all this other stuff. He just gradually came around to where his views were the opposite of where they’d started out. And then, of course, he was the sworn enemy of everything artistic in rock’n'roll. He didn’t want things to be nice and by then he had this whole body of stuff to react against, like Sgt. Pepper’s, which he liked at first as much as anybody did, but then as time went on and it became sort of passe, he’d say, “What’s all this hippy dippy shit? Goddamn it, you just wanna have ’96 Tears’! You just wanna have one chord. You don’t want the guy to have a voice. You want it to sound like Iggy or Lou!” And that was his whole thing.

Lester was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the way rock’n'roll was progressing after ’67. He disliked rock’s new-found seriousness and sophistication, and the emphasis on virtuosity that came up with new guitar heroes like Hendrix and Clapton. “Apparently,” he wrote, “nobody ever bothered to inform nine-tenths of musicians that music is about feeling, passion, love, anger, joy, fear, hope, lust, EMOTION DELIVERED AT ITS MOST POWERFUL AND DIRECT IN WHATEVER FORM, rather than whether you hit a clinker in that third bar there. I frankly wouldn’t expect most musicians to be able to figure this out for themselves, as you’d think absolutely anybody could, because it is a fact that nine-tenths of the HUMAN RACE never have and never will think for themselves, about anything.”

Along with his regular staples like Coltrane, Mingus and the Stones, Lester gravitated increasingly to the simplistic, unpretentious music of garage bands like Count Five, ? & the Mysterians, and the Seeds, as well as old doo wop, and the noisy, eclectic sounds of bands like the Velvet Underground, the Fugs, and Captain Beefheart.

You should have seen the looks that’d come over the faces of my ’68 roommates, who laughed at doo-wop but played Cream every day, when I put on White Light/White Heat, which I did every day. They let me know they thought I was a closet queer. Why else would anybody listen to such shit? I didn’t go around shoving my prejudices down everybody’s throats. I just endured Cream every fucking day, “Spoonful” and all the rest of that whiteheap bigdealsowhat. And you’d think it’d only be fair for them to endure Velvet Underground, Count Five, Oldies But Goodies, the Fugs, the Godz and I forget what other godawful racket I doted on. But they wouldn’t let me have my equal portion of obnoxiousness. My music was “bad,” and theirs was “good.”

But what was on the record player was only part of the Tobacco Road experience. A house full of Hells Angels next door provided an interesting sideshow…

ANDERSON: I remember him talking about these bikers he hung out with at The Roaring 20s. This was before Tobacco Road, but I assume that was the Tobacco Road connection for him and Butler and those other guys. He told me about some biker who took way too much acid and had this horrible bad trip, so he locked himself in his room and put on the single “Talk Talk” and listened to it over and over again for 24 hours.

BUTLER: These bikers had the very next door house, and they came over from time to time and we’d jam. I had a power trio. The drummer of my trio, John Horisyk, also lived with us, and another guy who was a pot dealer also lived there. One time the Angels came over and brought some joints and we smoked ‘em and got really wigged out. The Angels told us afterwards that the joints had heroin in ‘em! Lester just got real high and sat in a corner.

The biggest story from that whole episode was when the Hell’s Angels abducted a woman at gunpoint from a local bar and sexually abused her for a couple of days. They didn’t take her to our house; they took her next door to the Angel house. I heard all kinds of gang bang rituals went on. When they let her go, they told her if she went to the cops they’d kill her and her family and everyone she knew and everything. But she immediately went to the cops and they immediately came out and busted them.

I had moved out a couple of weeks before, thank God, but the cops, while they were busting the Angels, just for the hell of it, took one look at our house and busted that one too. The drummer and the drug dealer guy had a bunch of pot, bags of pot they were selling for a living, and they got busted too. I think Lester got busted in that bust too. He was living there but I don’t think he was dealing. He never dealt drugs, but he certainly used enough of them.

ANDERSON: I wasn’t around for the bust but Lester wrote about it in his journal and it was a big event for him. He was very proud about what he’d written about and read it to me and to other friends of ours.

After the bust at Tobacco Road in late ’68, Lester moved back in with Norma on First Avenue. He continued attending Grossmont and working at Streicher’s, and by all accounts something of a ‘drying out’ period took place…

ANDERSON: By ’67 he was already drinking a lot of cough medicine and also taking a lot of this other stuff; bad, bad stuff. He tricked me into taking Mezerine which is a motion sickness pill. He said, “Yeah, y’know, it’s really great! You take ten of them.” So I went and did it and I had the worst experience of my entire life! And he was just using me as a guinea pig, and then he went and tried it. He’d take all of this stuff and he’d take huge amounts of it.

Anyway, there came to this point when he was still at Grossmont and I was at San Diego State and we weren’t seeing that much of each other, and apparently he came to the point where he felt he was one step away from total disability or death. He went and saw a doctor and the doctor said, “Yes. You’ve really compromised your nervous system,” and all this other stuff. So Lester pretty much turned over a new leaf—or thought that he’d turned over a new leaf—and went through a long period of time where I don’t think he was taking much. He spent a lot of time by himself, isolated from everybody else. He worked at the shoe store, saw Andi some, and worked a lot of crossword puzzles.

He told me while this was going on that one of his big problems was boredom, and that he was just bored with everything. For some time the idea was that he had made up his mind that it was not possible for him to do this any more. On the other hand, it wasn’t like he had said anything categorical about it, so he would take speed occasionally and smoke pot occasionally, and, y’know, as the months turned into years it just got back to where he was hellbent-for-leather all over again, and whatever damage the doctor said he had done to his nervous system became a matter of small concern.

It was not long after this that things started to happen for Lester. His first review (of the MC5′s Kick Out the Jams) was published in Rolling Stone in April 1969, and all of a sudden it seemed he had found his true calling —perhaps, unthinkably, even a “career.” He wasn’t a shoes salesman, he was a “rock writer,” one of the first. His friends were suitably impressed…

ANDERSON: I don’t think any of us knew that he had tried to publish with Rolling Stone until that MC5 review was published. I don’t believe he told us that he had been doing this. I think we assumed, once that he was published, that that was what he was going to do, ‘cos we were all totally blown away. We were totally impressed—and we were right to be. We thought this meant he had found his niche, and we were right, he had. Especially because he continued to have a lot of things published. It wasn’t like there was a lot of lag time after that first review. In almost no time he had an ongoing relationship with Greil Marcus, who was the editor of Rolling Stone, and every day in the mail the albums were coming in from the record companies, which was a godsend to him because, not only did he get to listen to everything, but he had a ready source of cash, because he could take ‘em down and sell ‘em, the ones he didn’t want to keep.

He got a Christmas card from Elvis and the Colonel a year or so after he’d started doing all this. It happened very quickly. He’d only been doing it for a few months when Rolling Stone, which was still in San Francisco, brought him up there for a few days and he stayed with Greil Marcus and hung out at the Rolling Stone offices.

RACHAC: When he started writing for Rolling Stone, he was getting a lot of promotional stuff and it was a treat going over there each day ‘cos he’d always have a big package of new albums that had just come out. A lot of times he would give me records to take home and he’d say, “What do you think of this? Tell me.” It got to the point where he’d start picking out things he thought I would like, very pop-oriented things that he was sent. He himself would keep some of the more adventurous type of rock’n'roll at the time.

It was around that time we’d start playing “Make It or Break It,” ‘cos he really didn’t have the time to sit down and listen to everything they sent him. “Make It or Break It” was a game where we’d take out records, be it 45s or albums, to Wells Park. At that time there was access directly between his apartment building and the park. We’d actually go out to the park and throw records across the parking lot into the other side of the park. These were usually artists who were not too well known or of questionable value just by looking at the album cover. If they looked like they could play after we had done that, we’d more than likely give them a try. And if they didn’t, we’d either leave ‘em there or thrash ‘em. There’s probably still chips of ‘em out there in the parking lot.

I remember when he got the first Stooges album and then Funhouse. I went over there and he had the white Elektra promo label on the box. I really couldn’t understand what he saw in it the first time I heard it, but after awhile it started to grow on me. I figured, “What do you want with a quasi-Stones sound?”—which is all I heard in it the first time. But of course Lester championed them from Day One. He’d go around singing “TV Eye” to me all the time.

Lester himself described the effect the Stooges and their rare ilk had on his life in the third installment of an article called “The Roots of Punk,” which he wrote for a short-lived mag called New Wave in 1977:

The point for me and my friends in El Cajon who sat around every night of the week getting fucked up on booze and weed and speed and downs and whatever else we could lay our hands on while listening to “Sister Ray” and The Stooges and the MC5—which I’d learned to love —and Black Pearl and anything as long as it was noisy and offensive, the point was just that “1969″ was just two chords crashing into each other like downed-out meteorites, that trained monkeys (meaning somebody like us) coulda played ‘em, that “1969″ featured the only use of wah-wah that I had ever liked on any record (mainly because Ron Asheton didn’t do anything with it, no flash bullshit, he just blanged out a chord and let the technology play its own self), and most importantly of all, THAT IGGY DIDN’T GIVE A SHIT ABOUT ANYTHING AND NEITHER DID WE.

Lester’s words looped across the page with the same free flowing, high intensity, high energy, high volume noise as the Stooges’ sonic squall. He continued to write incessantly, fueled by his manic enthusiasm for the music.

RACHAC: He was always working around me. A lot of times he used to have his typewriter on a piece of plywood. He’d sit there and he’d balance it on his gut, and he’d hold a beer on it while he was doing this type of routine. He’d say, “What do you think of this?” and he’d read me something. Of course I was in no position to give him any kind of critique. I’d just say, “Oh, that sounds great.” I would nurture him in that regard.

Basically he would write a whole piece one time through, then go through it and pick it out and edit it. A lot of times he would send the manuscripts in with just his little marks out. He wouldn’t retype it at all. He flowed; he really flowed. He was a prime example of how a writer should work. He said everything off the top of his head. He was a real work machine in that regard. Very definitely, what you would read was basically how he would talk.

As Lester’s writing career took off, his aspirations as a musician took a back seat for several years, although, socially he was still up for making some music, should the situation arise, and, drunk on booze or Romilar would pontificate about forming his own band.

RACHAC: There was a lot of music making, so to speak, at his house. I can remember bringing my guitar over a lot of times and playing with him. Him playing harmonica and Roger playing sax; we had a strange contingent of instruments a lot of times. We’d do a lot of standards like “Who Do You Love” and these outrageous renditions of Bo Diddley songs. I can remember doing “Spider and the Fly” with him playing harmonica, “Pushin’ Too Hard,” of course. That gets a bit redundant on an acoustic though.

We’d talk all the time about forming a band. We had a lot of names we were gonna call ourselves: Cannibal Rape Job, The Loons, The Hounds— a lot of stuff was very Beefheart sounding, I remember. I don’t think Lester was really under any great delusions of trying to make any money playing music. He knew that his talent was in writing. He was a big San Diego icon at the time, among the rock’n'rollers who knew what was going on, mostly East County people.

Lester would still get up and play some harp with his old friends from Thee Dark Ages, who had by this point evolved into Funky Buckwheat and then Glory. The band played frequently at Chetley Hall on Greenfield in El Cajon and later at Jerry Herrera’s Palace in San Diego.

RANEY: Once he started getting kind of big time with the reviews then he kind of took off on all of us, I guess, but every once in a while he’d come by. He really liked the original formation of the Glory Band with Mike Millsap and everybody. He’d come by and sit in with us too. That’d be down at The Palace. We had him and Roger Anderson both sit in a few times. We had that big long version of “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl” he’d play on, and he used to sit in on “Bring It to Jerome,” which would turn out pretty cool. Being down at The Palace in the psychedelic days, in its whole heyday, the thing’d last for 30 minutes or something. That might have been the time he looked back at my amplifier and looked at me and said, “Who threw that orange?” And there wasn’t anything there!

RACHAC: We’d go to clubs quite a lot and see our friends’ bands and we go to other shows, big shows. We saw the Velvet Underground at the Hippodrome which was on 2nd and Market downtown. I remember Lester having access somehow and we got backstage. Of course, I was completely taken aback by these people. I wasn’t really that much into meeting them, but it was a big thing with Lester. He was standing there with his little microphone talking to Lou Reed, who was sitting in his chair with these wraparounds on. I remember that Roger and Lester went to see the Velvets again up at the Whiskey about three or four months later.

ANDERSON: Lester was just about the only critic who had any use for the Velvets, and he fairly quickly started causing other critics to see what the deal was. When Loaded came out (1970), he told me, “This is it! The Velvets are gonna turn into the biggest thing since the Beatles. They’re gonna be the American Beatles.” And I loved that album. I loved the Velvet Underground, but I thought he was nuts. He was really thinking in terms of worldly success for the Velvet Underground, right then. Little did he know that when he said that they were already broken up and he just didn’t know about it yet. But he was actually seeing into the future. He was seeing what would come to pass long after the Velvets had broken up, like ten or twenty years later what a huge influence they were gonna be. And he was right on the money. He was more on the money than he had any way of knowing he would be. He was the one who kept the flame burning.

ANDERSON: Lester was just about the only critic who had any use for the Velvets, and he fairly quickly started causing other critics to see what the deal was. When Loaded came out (1970), he told me, “This is it! The Velvets are gonna turn into the biggest thing since the Beatles. They’re gonna be the American Beatles.” And I loved that album. I loved the Velvet Underground, but I thought he was nuts. He was really thinking in terms of worldly success for the Velvet Underground, right then. Little did he know that when he said that they were already broken up and he just didn’t know about it yet. But he was actually seeing into the future. He was seeing what would come to pass long after the Velvets had broken up, like ten or twenty years later what a huge influence they were gonna be. And he was right on the money. He was more on the money than he had any way of knowing he would be. He was the one who kept the flame burning.

Years later, with the punk rock explosion of 1976-77, Lester’s championing of the Velvets was vindicated. Naturally, he was less than pleased about it though, because, inevitably, everyone HAD IT FIGURED ALL WRONG! In 1981 he wrote:

Nowadays everybody and his brother saunters around intoning the sacred words “Velvet Underground,” and every cheapjack-nihilism band who can’t play and don’t do that or anything else with any style gets called “the new Velvet Underground.” Now, what I’ve long suspected is that the people today dropping “Velvet Underground” all over the place are the EXACT SAME PEOPLE who in 1967-68 woulda called ‘em what they got called then, Faggots Who Couldn’t Play their Instruments, and that furthermore none of these namedropping assholes actually sat around listening to “Sister Ray,” for fucking pleasure, ever.

Words that apply today as much as they did back then.

RACHAC: I have a good story about Lester pulling me out of my parents’ house when I was about 16 and asking me if I wanted to go to State College to see this poet. I agreed, and me and him and his girlfriend Andi, the three of us went up to State College. Lester had just finished his first book, which has yet to see the light of print, called Drug Punk. It was the capers of all of us around the Valley at the time, kind of a Fear and Loathing. We ran to the University library, xeroxed off the entire manuscript, and went down to the side of the stage at the Bowl there, and it was Ginsberg. He did two sets and during the break Lester goes, “OK Rachac, let’s go,” and we went up to the back of the stage and Lester goes up to Ginsberg and says, “Mr. Ginsberg, Mr. Ginsberg. Hi, I’m Lester Bangs. I write for the Rolling Stone.”

And Ginsberg just floored Lester. He said, “Yeah, I’ve read you.” Lester went on to say he had this manuscript, “Could you read it?” Ginsberg agreed but couldn’t guarantee he would respond. Well, as it was, about six weeks later we were at his mom’s apartment there, and bigger than shit he got a postcard from Ginsberg that told him that he really liked what he was doing. But I remember the line Ginsberg put: “But I think you should write more telegraphically, like me.” Now “telegraphically” took me a little while to figure out, but I know now it’s like “America, go fuck yourself with the atom bomb stop.”

One thing he always bestowed upon me was that “Rachac, we’re living history, and you make your own history. These vicarious warts that sit around and dream about the history of the past, they don’t utilize the lives that God had given them to make their own.” And it’s true. A good way to look at the world in general and your life in particular is that you’re living history. We’re here to make an impression one way or another in that regard. It was one of the first things I remember him talking about.

He was one of the most likeable individuals I’ve ever been around. Apart from his mystique, he was a brilliant guy, needless to say. I, up until that time, had been hanging around with nothing but rock’n'rollers on a musical level, and all we were talking about was three chords and where to plug your amp in and stuff. When I got around Lester and his little circle, it was Kerouac and Coltrane and things I had never heard of. It was really beneficial to me. It put me years ahead of my rock’n'roll contemporaries. I’d spend a week around Lester and get back around my band friends and I’d look at these people like “You guys don’t have a clue, do you?” It was really eye opening and really ear opening too. He really gave me a booster shot in that regard, as far as the counter culture goes. And I really needed it.

Gary Rachac’s younger sister dated Lester for about five months in 1970, while Gary was vacationing in England.

DEBBIE RACHAC: Lester was working as a shoe salesman down at Streicher’s in Mission Valley. I was shopping for, I think, school clothes or something and I remembered that he worked in that area in Mission Valley, so I went by there and said “Hi.” I tried on a lot of shoes and boots and stuff and bought a couple of things. That’s when we first met. He was very professional, the basic salesman, helping people and getting all the shoes. I probably tried on 20 pairs of shoes that day!

I was probably 16-and-a-half and he was 21; very worldly, to me. He asked me if I wanted to go out and I said, “Yeah, that would be fun.” Our first date we went out to see the Woodstock movie, it had just opened. It was a bit of an adventure getting there ‘cos I told him I would drive and I only had my learner’s permit. I had never been on the freeway before. We had borrowed my dad’s car and I got on the freeway and I almost got in a couple of accidents! He was advising me,

like, “Look out!” So he drove home.

One thing that was kind of funny was that his apartment was across the street from my high school and so when I would go out for gym class he’d always meet me and we would talk through the chain links.

He seemed like basically a happy person. I wondered about his dad, but I never asked, only because I was a little uncomfortable with it. I didn’t know if it was something that was painful for him. There were times where maybe I should’ve asked. Maybe he wanted to talk about it. But that was probably the only thing I questioned that he was not happy about. I didn’t see the presence of a father figure and I wondered what was going on with that ‘cos I was in a traditional kind of situation as a family. Other than that he seemed fairly normal. He felt very strongly about his writing. He channeled a lot of energy into that. That seemed like a positive thing to me at the time. That sort of a life can take you all different avenues and its unfortunate the avenue in the end that it took, but at that time it was a very positive thing for him.

MELTZER: When I first met him he was still living down there in San Diego somewhere. It was early ’71. Grunt Records, RCA—Jefferson Airplane, all those bands—had an unveiling somewhere in San Francisco. They used some big warehouse place. They flew a lot of people in from all over the country and so I met Lester there. We’d talked on the phone before that and wrote. He had this girlfriend with him and they showed everybody how to do the Funky Penguin—whatever that was—and it was not especially outwardly, conspicuously self-destructive as to the way he behaved. He just seemed young and earnest. Just a happy kid. And for two days, or whatever it was, he seemed OK.

The next time I saw him was somewhat later that year. It was a Blue Oyster Cult press party when they first got signed to Columbia. He flew to New York and he stayed with me, and this was the second or third time I saw him. I think he was still living in San Diego, and he was just completely, constantly drunk. There was just no moment where he wasn’t drinking—for three days. And so I realized that he was a very variable guy.

Tosches, his take on Lester when Lester died was, “While anybody might tap their knee or nervously play with a pencil at some point in the course of a day, Lester’s whole body was that kind of twitch every moment he was alive.” He was on some kind of auto-pilot that he had no control over at all, that only varied in terms of what the emotional input or the chemical input might be in a given day.

By 1971 Lester’s work was being published with regularity in both Rolling Stone and Creem, and the horizons of El Cajon Valley were starting to seem more like walls. “To make a dismal story mercifully short,” he wrote, “I discovered a magazine in Detroit called Creem, whose staff was so crazy they even put the Stooges on the cover. Of every issue! So I left my job and school and girlfriend and beer-drinking buddies and moved to Detroit where my brand of degenerate drool would not be tolerated but outright condoned.”

Within a few months he had taken over as editor. He was at Creem until 1976, though he continued to write for various other publications, including Rolling Stone (until 1973 when Jan Wenner banned him for “disrespect to musicians”!). It was during this period that some of his most (in)famous pieces were published: “James Taylor Marked For Death” (a multi-thousand word rant banged out in 26 straight hours of typing, according to Lester, about the greatness of the Troggs and the insipidness of singer-songwriters) in Greg Shaw’s Who Put the Bomp fanzine, “John Coltrane Lives” (a hilarious true story about Lester’s aspirations as a free jazz saxophonist and the resultant confrontation with his El Cajon landlady) and a notorious series of antagonistic interviews with Lou Reed.

ANDERSON: We didn’t really have time to think that this was anything but some definite good thing that was happening for him. We had no way of knowing that he was gonna turn into this seminal character and define exactly what rock criticism was all about. As far as I can tell, looking back on it, he invented punk rock and he invented heavy metal, because he invented both of those terms. He was using the term punk rock in 1972. He was talking about the Stooges and using the term punk rock.

To me, basically—besides the excitement of his writing—his big contribution was that he was a cultural arbiter, an arbiter of aesthetics, who looked at what was happening with music and said. “This is what music should do.” And then periodically he would look out and say, “This trend is wrong. This trend is bad. This trend really bites. This other stuff over here is where we want to be.” I think his taste had an enormous influence.