-

Featured News

Patti Smith Upcoming Tour for 50th Anniversary of Horses

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress

By Harvey Kubernik

“Horses was like the first cannon blast in a war – frightening and disorienting. I mean, she was so unlike the FM radio terrain in every way. She was literate, aggress -

Featured Articles

Chasing the White Light: Lou Reed, the Telepathic Secretary and Metal Machine Music

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers

By David Holzer

Fifty years ago, Lou Reed released Transformer. In among “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Make Up” and “Vicious,” cuts that would launch a cartoon Rock N Roll Animal pers -

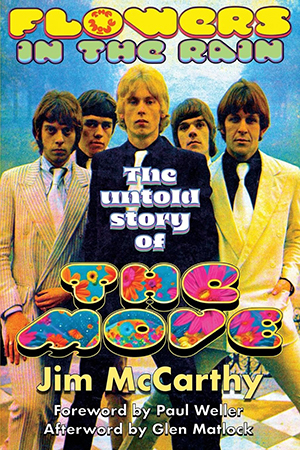

FLOWERS IN THE RAIN: THE UNTOLD STORY OF THE MOVE by Jim McCarthy

(Wymer, 2024, 403 pages)

Review by Alan Clayson

Because I found Jim such a nice bloke during correlated e-mail correspondence, I don’t want to give his diligently-researched work a rubbishing. Yet it has to be said that, perhaps through ham-fisted sub-editing, sentences are often split up. Like this. Which may prove irritating. So might factual and syntactic repetition, and, in the process of scene-setting, going off on not entirely relevant tangents. Moreover, the lack of an index may frustrate anyone seeking raw information. In this regard, a few minor errors might not matter. For example, while it’s correct that the use of Tchaikovsky’s “1812” riff in “Night Of Fear,” the maiden A-side that kicked off the Move’s five-year run of domestic hits, was pre-empted by Ike and Tina Turner in their “Tell Here I’m Not Home” opus, this came out in 1964—not 1966. Also, it’s Johnnie Ray not Johnny Ray, and what’s this about ‘Clifford Bennett and The Rebel Rousers’?

The reader is left too with unanswered questions. Why, say, was Roy Wood expelled from Moseley College of Art? Was Tamla Motown’s cosseted Little Stevie Wonder really among four mere support acts to the Move at Birmingham’s Club Cedar on February 3, 1966? What was the genealogical connection between Unit 4 + 2 and Tomorrow figured out by an author given to mixed metaphors—e.g. “the weak link in the chain is the one who becomes the sacrificial lamb”—and opinionated digs at the respective likes of Ginger Baker (“a clodhopper of a drummer”) and Syd’s Pink Floyd (“half-assed playing, sloppy drumming, allied to pretentious lyrics. Middle-class student music”)?

Yet, if nothing else, this offering is more than simply thorough—as demonstrated by both 1967’s “Wave The Flag And Stop The Train” flip-side featuring “a wonderful, harmonized confusion of vocals between 1:39 and 1:50 seconds,” and maybe too much detail about a particularly sick-making jape in the van between gigs. Crucially, the account is carried by McCarthy’s infectious enthusiasm that, if over-effusive sometimes, tells an intriguing tale rooted in grassroots struggles of the West Midlands beat groups from whence would spring in 1966 the ‘classic’ line-up of the Move, i.e. singer Carl Wayne with guitarists Roy Wood and Trevor Burton, drummer Bev Bevan and Chris ‘Ace’ Kefford on bass—who all took lead vocals at designated points during a stage presentation involving fireworks, smoke bombs, lighter fluid and Wayne charging about with an axe to implode televisions and hack at effigies of political personages like Prime Minister Harold Wilson who, after being caricatured in a rude postcard circulated to publicize 1967’s “Flowers In The Rain” single , won a libel suit against the quintet and their manager, Tony Secunda (“almost ‘situationist’ in his preferred style of creating chaos,” writes McCarthy).

Before the year was out too, the discords and intrigues that make pop outfits what they are had started to overwhelm the Move. First to go was Ace Kefford, given pride of place on the book’s front cover, having been singled out loudly by a prominent London promoter as the combo’s chief visual selling point—with all the concomitant resentment—for his Norse god androgyny with underlying dread. He was also a composer whose efforts were marginalized by Wood’s near-monopoly of originals. Indeed, Kefford was responsible for “William Chalker’s Time Machine,” the best-remembered 45 by the Lemon Tree—which had it been attributed to the Move, would have been a sure-fire smash.

Effectively, Ace sacked himself after starting to go the same brain-frazzled way as Syd Barrett when the Move and Pink Floyd were each on a round-Britain package tour with the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Amen Corner, that, in less absolute fashion, was on a par with that fated “scream circuit” trek in 1960 co-headlined by Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran.

Kefford’s creation of “a hole that was never filled” did not, however, impede the Move’s onwards-and-upwards trajectory as they scored a Number One with “Blackberry Way,” although during its Top of the Pops plugs, Burton’s constant scowl and Brooding Intensity became less an effusion of ‘image’ than the real thing. Irked by Wood’s increasing control of the ensemble’s destiny, he was soon to depart—as would Wayne, but not before the latter had advocated the Move’s unhappy stab at cabaret on the same bills as corny variety acts.

Bevan and Wood rallied by enlisting Jeff Lynne, X-factor of the picked-to-click Idle Race, but, garbed and painted like a psychedelic Wild Man Of Borneo, Wood was at the central microphone for “Brontosaurus” and remaining British chart entries during the three’s plotting of the Electric Light Orchestra and the late Carl’s discarded but “very cool and practical idea” of fronting a Move with Ace and Trevor back in the fold.

Flowers In The Rain also addresses the post-Move careers of all concerned, and a discography plus lists of electric media appearances and even the venues for cancelled tours in the USA (where the group surfaced only as cult celebrities) are included in the appendices of a history that, while it won’t win Jim a Nobel Prize for Literature, will serve as both a useful starting point for Move beginners and a necessary purchase for long-time devotees.