-

Featured News

Erkin Koray R.I.P.

By Jay Dobis

Erkin Koray, aka Erkin Baba, the father of Turkish Rock ‘n Roll (he put together the first Turkish rock band (Erkin Koray ve Ritmcileri) in 1957 when he was a high school student

By Jay Dobis

Erkin Koray, aka Erkin Baba, the father of Turkish Rock ‘n Roll (he put together the first Turkish rock band (Erkin Koray ve Ritmcileri) in 1957 when he was a high school student -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

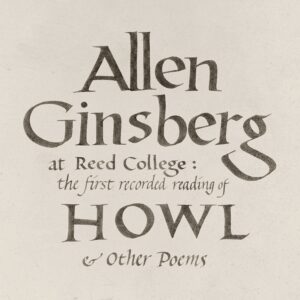

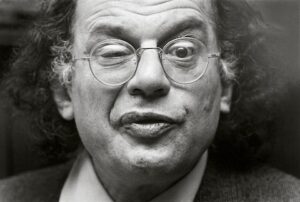

Allen Ginsberg At Reed College: The First Recorded Reading Of Howl

By Harvey Kubernik

On April 2, 2021, Omnivore Records will be issuing Allen Ginsberg At Reed College: The First Recorded Reading Of Howl & Other Poems.

A description of the product appears on the Omnivore website.

“Allen Ginsberg’s first public reading of his epic poem ‘Howl’ took place at San Francisco’s famous Six Gallery in October of 1955. Along with Ginsberg, the evening included readings by Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, Philip Lamantia, and Michael McClure. Poet and anthologist Kenneth Rexroth was the emcee, and Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Neal Cassady were in attendance.

“Unfortunately for literary history, no one recorded the Six Gallery reading, and it was long-thought that the first recording of ‘Howl’ was from a reading at Berkeley in March 1956. Before visiting Berkeley, however, Ginsberg had traveled to Reed College in Portland, Oregon, with Gary Snyder to give a series of readings. Snyder and Philip Whalen had been students at Reed and had studied under the legendary calligrapher Lloyd Reynolds.

“On February 13 and 14, 1956, Snyder and Ginsberg read at Reed, with the Valentine’s Day performance recorded then forgotten about until author John Suiter, researching Snyder at Reed’s Hauser Memorial Library, found the tape in a box in 2007.

“To reflect the distinctive culture of Reed College, Reed Professor of English and Humanities, Dr. Pancho Savery, wrote the liner notes and Gregory MacNaughton of the Calligraphy Initiative in Honor of Lloyd J. Reynolds created the cover in the style of what a poster for the event might have looked like hanging on the Reed campus in 1956. Savery’s notes trace the poem’s history and inspiration and highlight differences in this early, work-in-progress version to the final published text.

“Reading ‘Howl’ out loud in front of an audience is an exhausting and emotional experience, so Ginsberg warmed up by reading several shorter poems first. The Reed recording includes these shorter selections and most of Part I of ‘Howl.’

“The restored recording is crystal clear; you can not only hear Ginsberg turning the pages, but taking breaths after each long line. The audience is pin-drop quiet except for a few places in the reading, for instance, one moment when someone in the audience says something that can’t be heard that elicits laughter, to which Ginsberg responds, ‘I don’t want to corrupt the youth.’ Other lines generate laughter, but the audience is attentive and respectful, allowing for a present-day fly-on-the-wall listening experience. In testimony to how emotionally draining it was to read the poem two nights in a row, as Ginsberg launches into Part II, he stops after four lines saying, ‘I don’t really feel like reading any more, I haven’t got any kind of steam. So I’d like to cut, do you mind?’ Thus ends the first known recording of ‘Howl’… and now begins its 21st century access for all to hear.”

I KNEW ALLEN GINSBERG and interviewed him at length three times. I also co-promoted several of his Southern California readings in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, and produced a live recording of him in 1982 at the Unitarian Church.

My first Ginsberg interview initially appeared in 1996 in HITS Magazine and a very short edited version appeared in The Los Angeles Times Calendar section on April 7, 1997 when the daily newspaper asked me to pen one of the tribute stories on Ginsberg when he died. During 1999 a portion of one of my interviews was published in The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats. In 2007 I wrote the liner notes to the first-ever CD release of Ginsberg’s Kaddish for Water Records.

I provided handclaps on two tracks with Rodney Bingenheimer on the Leonard Cohen album Death of a Ladies’ Man produced by Phil Spector at Gold Star Recording Studio in 1977. On one cut Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan join Leonard on “Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On.” Stan Ross and Larry Levine engineered these sessions. Leonard and I went to see Ginsberg read at The Troubadour club in West Hollywood. At the time I was doing a series of interviews with Phil and Leonard before and after they did that LP.

In December of 2005 I spoke with legendary record producer and author Jerry Wexler, then a partner in Atlantic Records with Ahmet and Neshui Ertegun. In January 1965, Ginsberg had signed a record contract with Wexler’s landmark Atlantic Records label to distribute his live performance of Kaddish on an album.

“For me it all began with ‘Howl,’ and then when I read ‘Kaddish,’ it stirred the dark Yiddish currents in my own blood. I experienced the joy and anguish, the exaltation that great poetry will bring on,” Wexler reminisced. “I don’t recall when or how I met Allen, but I telephoned him to see whether he’d be interested in recording ‘Kaddish’ for our record company. Better than that: he had taped a public reading at Brandeis, and it would remain only for us to do the manufacturing: the album design, the cover photo, the mastering.”

Wexler later went on to produce (with Barry Beckett) Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming and Saved albums, and saw a relationship between Ginsberg and Dylan.

“Absolutely, they both were geniuses, top of the line. Allen Ginsberg may not have influenced the generation as such but he sure influenced a hell of a lot of writers. And Bob Dylan, of course, changed the culture. So there is a correspondence between the two guys,” reinforced Wexler.

In 1975-1976, Ginsberg toured with fellow Gemini Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue and appears in Dylan’s Renaldo and Clara movie. The soundtrack of the film includes excerpts from Ginsberg reading “Kaddish.”

When Allen Ginsberg died at age 70 of liver cancer and hepatitis on April 5, 1997 at his East Village loft in New York City. That evening Bob Dylan was playing a concert at the Moncton Coliseum in Moncton, New Brunswick, and dedicated “Desolation Row” to him. Dylan had not been including the song in recent shows.

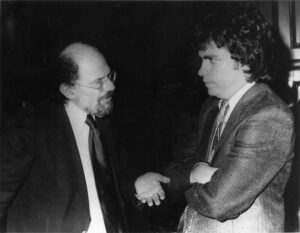

Allen Ginsberg and Harvey Kubernik. (Photo by Suzan Carson)

Harvey Kubernik and Allen Ginsberg 1994 and 1996 Interviews

Q: What kind of impact did FM Radio actually have on you as a writer and reader/ performer?

A: By the time I got around to getting on the radio, it was actually an AM station in Chicago with Studs Terkel; recorded the complete reading of “Howl” in Chicago, later used for the Fantasy record. It was broadcast censored. ‘59. KPFA in the Bay Area then started broadcasting my stuff in San Francisco, a Pacifica station. Fantasy put out “Howl” and that got around. Then, Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, put out “Kaddish.” It was radio broadcast from Brandeis University.

Q: What do you want from FM radio?

A: I’d like for some FM station to play all four CDs of my Holy Soul Jelly Roll: Poems And Songs 1949-1993 one night, announced in advance so everybody could listen to it, and I think it would change not only heads, but expand people’s emotional range. “All the time in eternity in the warm light of this poem’s radio.” That was 1953. So I was aware. I was laying out treasures in heaven, basically. I knew that after I was dead my stuff would slowly seep up, so I’m really glad I’m alive to put this (box set) recording together.

Q: Was there ever a conflict of written page origin then into audio land?

A: We wrote, and we were in the tradition of William Carlos Williams’ spoken vernacular, comprehensible common language that anyone could understand, coming from Whitman through William Carlos Williams through be-bop. We were built for it. I can talk. I’m an old ham.

Q: Does the vision change once it leaves the paper?

A: No. It doesn’t make much difference. The method of my writing to begin with is that I’m not writing to write something, is that I catch myself thinking; I suddenly notice something I have thought of when I wasn’t thinking of writing, and then I write it down if it is vivid enough. And as far as the choice of what to write down or not, the slogan is vividness, is self-selecting. So in a sense, the method is impervious to influence by the audience because I’m just thinking to myself in the bathtub.

Q: What about poetry readings and performances? Is it different reading with a musician next to you or now a bunch of people sharing the stage?

A: I have to focus on my text. I’m still pointing toward the tornado.

Q: You still read from text on stage, from a book or typewritten. Do you ever read from memory?

A: I rarely read from memory. I sing from “Father Death Blues,” and can sing “Amazing Grace” from memory, but I don’t know what lines are coming, so I have to refresh myself. I’m not particularly interested in memorizing perfectly ‘cause I think it’s distracting from interpreting the text differently each time. I think you have to have all the dimensions at once, the book thing, the poetry thing, plus the performance, plus the musical accompaniment, and if you have all of them, and they’re all in a good place, that’s fine.

But the reason I don’t try to memorize, I guess I could, but I’m too busy, and I like to re-interpret the poem each time. Certain cadences are recurrent and certain intonations are recurrent, but on the other hand, if I don’t memorize it, there’s always the chance that somebody noticing something, and empathizing puts it a little differently, and bringing out meaning that I didn’t realize before. So I prefer to have the score in front of me and interpret it new each time.

Q: Artists from new generations, alternative rock bands, still keep discovering your work and acknowledging your influence.

A: It’s fun. You always learn from younger people. I learned a lot from William Carlos Williams, and the elders of my generation. People who were much older than me when I was young. And that inter-generational amity is really important because it spreads myths from one generation to another of what you know, and all the techniques and the history. At the same time, Williams learned connection with Corso and myself and (Peter) Orlovsky. Renewed his lease, so to speak. And the advent of The Black Mountain Beat Generation Poetry Renaissance, San Francisco, really renewed his poetic life, in a sense, brought him out to the public and his mood of poetry. . .as the mainstream, rather than as the eccentric jerk from New Jersey.

All of a sudden, with the phalanx of younger people following his lead, he became the sage that he was. And I think it gave him a lot of gratification to realize he had been on the right track, and that it wasn’t in vein. And I get the same thing whenever I get to work with younger people. And I learn from them. I don’t think I would have been singing if it wasn’t for younger Dylan. I mean he turned me on to actually singing. I remember the moment it was. It was a concert with Happy Traum that I went to and saw in Greenwich Village. I suddenly started to write my own lyrics, instead of Blake. Dylan’s words were so beautiful. The first time I heard them I wept.

I had come back from India, and Charlie Plymell, a poet I liked a lot in Bolinas, at a “Welcome Home Party” played me Dylan singing “Masters Of War” from Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and I actually burst into tears. It was a sense that the torch had been passed to another generation. And somebody had the self-empowerment of saying, “I’ll know my song well before i start singing it.”

Q: Can we talk about talent scout and record music executive, John Hammond, Sr., perhaps the A&R man of the century? I met him once. Wonderful man.

A: I visited him in the hospital, on his deathbed, years ago, and our final conversation was about Robert Johnson and Bob Dylan. Well, I think I ran into him in the early ‘60s. He knew my poetry quite well. But it was around the Rolling Thunder Review with Dylan that we got more intimate. I had already made one recording, William Blake’s Songs Of Innocence And Experience, in 1969, with some very good musicians, including Julius Watkins on French horn, Don Cherry, Elvin Jones used them. And also Herman Wright, a bassist that was suggested by Charles Mingus. Mingus encouraged me to do the Blake. So I had something to play.

I was on the Rolling Thunder tour, doing a little singing, and I had a whole bunch of new material I had done with Dylan in 1971. In 1971 Dylan and I went into a studio and improvised. I had 40 minutes of music with him. So I brought that to Hammond in 1975, after the tour. I had a bunch of new songs and he said, “Let’s go in the studio and make an album.” I had some musicians who had been with me since 1968 or 1969 since the Blake. David Mansfield from the Rolling Thunder tour, and a wonderful musician, Arthur Russell, who Philip Glass has just put out posthumously on Point Records. Arthur Russell lived in my apartment building, upstairs, and had accompanied me across country on tours, and managed The Kitchen in New York. We had a good little group of musicians.

Dylan made a record in the Columbia Studios. It was the first time I didn’t have to pay! Then, Columbia wouldn’t put it out because of dirty words they said in those days. The anti-smoking, “Don’t Smoke” poem. So things were in a stasis, but I continued recording myself in 1981, did a whole series of recordings with David Amram, by this time I was working with Steven Taylor, now the lead guitarist of the Fugs. He’s also the lead guitarist for the False Prophets, a punk garage band.

So we got together at CBS Studios and did another 40 minutes of music, and later, John Hammond put the two together. He had left Columbia and started his own label, John Hammond Records, to be distributed by Columbia. So he not only put out what he did with me, he put out a double album, and he got Robert Frank, who had done the (Rolling Stones) Exile On Main Street album cover, whose an old friend, to make a composite for our cover, and there was a really good play list inside, and the text was a good deduction.

However, the record didn’t sell. Before I had a chance to rescue the further 10,000 copies they (Columbia) had, they shredded them, so they were gone, and a rarity now.

Holy Soul Jelly Roll: Poems And Songs 1949-1993 is a summary of all the studio recordings I did, plus a lot of other stuff that was never done in a studio, but done in readings, plus another album with Blake, including Dylan on Blake, and a duet with Elvin Jones, including some work with Dylan out in Santa Monica in 1982 in his studio, the live Clash cut, and an excerpt from the opera I did with Philip Glass. So the range runs from a cappella up through folk, punk, dirty blues, classical, collaborations with Dylan, some rap, percussion and vocal with Jones. David Amram was on it as well.

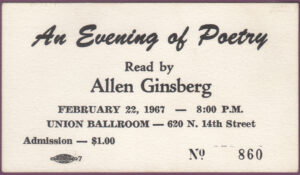

Ticket for a 1967 reading. (Courtesy Roger Steffens)

Q: With the release of your box set, Holy Soul Jelly Roll: Poems And Songs 1949-1993, the vinyl-to-CD reissues, new audio recordings, is this further proof of the literature living and breathing?

A: The actual texts however, have not been re-written, and are now coming up to more public notice like Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, and Kerouac’s new, unpublished poems, and for the first time, my actual voice available on a bunch of CDs, going all the way back to 1949 and stretching up to 1993, with the very first original reading of ‘‘Howl,” which is sort of a standard anthology piece, that has never been heard, or a poem like “Sunflower Sutra” or “America,” which was standard in the Norton anthologies in high school.

Q: I know that Burroughs introduced you to some key books in the mid–‘40s that were influential to your thoughts and writing, and Kerouac, around the same time, when you were attending Columbia University, maybe around 1950, had been into some form of Buddhism and spontaneous prose, but an older generation of writers had an impact on your eventual voice.

I joked when we were recording live and setting up the equipment “as far as New Jersey goes, it’s you, Bruce Springsteen and Frank Sinatra,” but you immediately added, “William Carlos Williams,” whom you met around age 20.

A: I knew him from my home town of Patterson, New Jersey. I’d seen him in 1948. He actually innovated the idea of listening to the way people talked and writing in that way. . . Using the tones of their voice and using the rhythmical sequences of actual talk instead of dat dat dat dot dot dot. “This is the forest…” Instead of a straight square metronomic arithmetic beat, there’s the infinitely more musical and varied rhythmic sequences of conversation as well as the tones. “‘Cause if you notice, most academic poetry is spoken in a single solitary moan tone that maybe doesn’t have the variety of when you are talking to your grandmother or baby.

It happens every 100 or 150 years. It did in the days of Wordsworth, who in his preface to lyrical ballads, suggested that poets begin writing in the words and diction of men of intelligence, or talk to each other intelligently, instead of imitating another century’s literary style. So, I think what happened is that we followed an older tradition, a lineage, of the modernists of the turn of the century continued their work into idiomatic talk and musical cadences and returned poetry back to its original sources and actual communication between people. That was picked up generation after generation up to people like U2, who are very much influenced by Burroughs in their presentation of visual material, or Sonic Youth, or poets, like Thurston Moore and Lee Renaldo are interested in poetry.

Q: You worked with the Clash on Combat Rock. How did “Capitol Air” come together, incorporated in this box set? I spun it on KLOS-FM when I did a radio interview two years ago on deejay Frank Sontag’s Impact shift and the phone lines lit up as if somebody won the lotto.

A: Well, it’s an accident. I wondered into a place called Bonds, which at that time was a big (couple of thousand people) club in New York. The Clash at the time had a 17 night run, and I knew the sound engineer, who brought me backstage to introduce me and Joe Strummer took one look at me and said, “Ginsberg, when are you going to run for President?” And then he said there was some guy that we’ve had trying to talk to the kids about Sandanistas and about Latin American policy and politics, but they’re not listening. They are throwing eggs or tomatoes at him. “Can you go out and talk?” I said, “Speech, no, but I have a little punk song that I wrote that begins, ‘I don’t like the government where I live. . .’

So, we rehearsed it for about five minutes during their intermission break and then they took me out on stage. “Allen Ginsberg is going to sing.” And so we improvised it. I gave them the chord changes. It gets kind of Clash-like good anthem, like music about the middle, but they trail off again. The guy who was my friend in the soundboard, mixed my voice real loud so the kids could hear, and so there was a nice reaction, because they could hear common sense being said in the song. You can hear the cheers on the record.

I wrote “Capitol Air” in 1980, recorded with the Clash live, in 1981 or ‘82. “Capitol Air” was written coming back from Yugoslavia, oddly enough from a tour of Eastern Europe, realizing that the police bureaucracies in America and in Eastern Europe were the same, mirror images of each other finally. The climatic stanza “No Hope Communism, No Hope capitalism”. Yea, “Everybody is lying on both sides.” We didn’t play the whole cut because we didn’t have enough time, but they built up to a kind of crescendo, which was nice when the whole band came in.

Q: You did a poetry reading in England with Paul McCartney recently.

A: I had a gig at Albert Hall in London. A reading. I had been talking quite a bit to McCartney, visiting him and bringing him poetry and haiku, and looking at Linda McCartney’s photographs and giving him some photos I’d taken of them. So, McCartney liked it and filmed me doing “Skeletons” in a little eight-millimeter home thing. And then I had this reading at Albert Hall, and I asked McCartney if he could recommend a young guitarist who was a quick study. So he gave me a few names, but he said, “If you’re not fixed up with a guitarist, why don’t you try me? I love the poem.” So I said, “It’s a date.”

We went to Paul’s house and spent an afternoon rehearsing. He came to one sound check, and we did a little rehearsal there, again. And then he went up to his box with his family. It was a benefit for literary things. There were 15 other poets. We didn’t tell anybody that McCartney was going to play. And we developed that riff really nicely. In fact, Linda made a little tape of our rehearsal. So, then, we went onstage and knocked it out. There’s a photo of us on the CD. It was very lively, and he was into it.

Allen Ginsberg and Paul McCartney, 1995.

Q: Didn’t you see the Beatles play, and there’s some poem you wrote about the event?

A: Yes! I saw them in Portland, Maine. I was up there with Gary Snyder, probably 1965, 1966. I was with a couple of little children. I had gotten tickets and was sitting way out in the bleachers, and John Lennon came out and said, “We understand that Allen Ginsberg is in the audience. So three cheers. So now we’ll have our show.” He saluted me from the stage, which amazed me and made me feel very proud with all these young kids at my side. Then I knew Lennon and Yoko Ono lived in New York and visited on and off. I was involved in some political things with them occasionally.

Q: You know, I originally felt when you first started writing in the ‘40s there really wasn’t any musical influence or instrumentation behind or around your words. Yet the first track on this box set recorded in the late ‘40s in Neal Cassady’s pad, actually has the radio playing in the background on the tape.

A: The first cut has a jazz background, because the whole atmosphere from 1940 and on was permeated with be-bop and (DJ), Symphony Sid.

Q: What does music and beat do when it’s added to voice and text?

A: Well, a whole mish mosh. First of all, I grew up on all blues, Ma Rainey and Leadbelly. I listened to them live on radio station WNYC, back in the late ‘30s or early ‘40s. So I have a blues background. There’s some sort of Hebrewic cantalation relation to the blues that I’ve always had. So the first thing on the collection is “When The Saints Go Marching In” that I made up a cappella when I was hitchhiking, and recorded in Neil Cassady’s house a year later. Then things like my mother taught me. “The Green Valentine Blues.” Just coming from everyone who likes to sing in the shower.

Then there was the poetry and music, King Pleasure, and the people who were putting together be-bop, syllable by syllable, like Lambert Ross and Hendricks. I knew them in 1948. We used to smoke pot together in the ‘40s, when I knew Neal Cassady, around Columbia when I was living on 92nd Street.

Q: Hey, I met drummer Freddy Gruber last week. Buddy Rich’s main man. Freddy told me you tried to hit him on once.

A: (laughs). I had a crush on Freddy. I saw him recently. Around 1944, ‘45, Kerouac and I were listening to Symphony Sid, and I heard the whole repertoire of Thelonious Monk, “Round Midnight,” “Orinthology” and all that. I actually saw Charlie Parker, weekend after weekend a few years later at The Open Door. And in the ‘60s, went night after night to The Five Spot to hear Thelonious Monk, and actually gave Thelonious Monk, “Howl”, and got his critique on it two weeks later when I saw him again. “What did you think of it?’ He said, “Makes sense.”

In 1960 I delivered some psilocybin from Timothy Leary to both Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie. And Monk said later on, “Got anything stronger?” Later on I spent an evening with him on what is now Charlie Parker Place around 1960. Also in San Francisco, in the mid-’50’s, there was a music and poetry scene. Mingus was involved with Kenneth Rexroth and Kenneth Patchen. And Fantasy records documented some of that. The Cellar in San Francisco. By that time, I didn’t know how to handle it, so I never did much of that myself ‘cause I was more funky, old fashioned blues. I couldn’t cut the mustard with free jazz. So then in the 1970s, I began turning on to Dylan. I knew him in the ‘60s. He taught me the three chord blues pattern. So he was my instructor.

Q: What happens when the beat or the music collides with your words and voice?

A: Elvin has a very interesting attitude. He feels that he’s not there to beat out the vocalist. He’s there to put a floor under them. He’s there to support and encourage, and give a place for the vocal to come in, not to compete with the vocal, but to provide a ground for it. He’s very intelligent as a musician. We did it once together in 1969 on the Blake album; there was military type drum, and then this recent rap song. I’ve got some other stuff we haven’t put out with Elvin. I’ve rarely found opposition to the music because the musicians were very sensitive, and built their music around the dynamics of my voice.

Q: Subject specific answer required: You write something on a piece of paper. Other people, musicians, come invited to participate and collaborate. Does the original intention become a different trip once there is music and other elements involved?

A: Well, it widens it into a slightly different trip, but the words are pretty stable, and they mean what they mean, so there is no problem. The interesting thing is adjusting the rhythmic pattern and the intonation to the musician’s idea of what there is there. That’s pretty good, because I’m good as an improviser, I can fit in, as you can hear on “Birdbrain.” Where I can take a long line or a short line and fit in sixteen bars without worrying about spaces and closed places.

Q: As far as performance and poetry readings, when you read in recital, aren’t you trying to keep the same original birthplace word vision and not expand or bring in theatrical elements?

A: I like to stick to something that is grounded in anything I could say to somebody, that they wouldn’t notice I was really saying it as poetry. Intense fragments of spoken idiom, with all the different tones of the spoken idiom, which is more musical than most poetry. Most poetry by amateur poets is limited to a couple of tones, a couple of pitches, instead of an entire range, so that the poetry we do fits with the music because it has its pitch consciousness. The tone reading the vowels up and down.

Q: Explain the use of chronology in the ‘90s, reading original work written and created decades earlier?

A: My background was William Butler Yeats. Seeing the sequence of his development, maturation and growth over the years was really interesting as a novel. How he began as a vague, misty eyed young 1890s devotee of Irish Mythology, and how he wound up, this tough old guy who put a skin on everything he said. So I like the idea of seeing the development of the mind, or of the voice, or of the thought, or of the poetic capacity, and I want to leave that trail behind for other poets so they could see where I was at one point, or where I was at another. My oration, my pronunciation or my singing, my vocalization differs, and it builds.

As I get older it gets more interesting with more and more tones, and more and more breath, and deeper and deeper voice and higher and higher voice. But still the original rhythms and the original ideas are from the original text, so you’ve still got a chronology going. So people could see the development of the mind. I’m not writing about the external world. I’m writing about what goes through my mind. So, at a certain period I’m interested in this kind of sex, another period, this kind of politics, another period, this kind of meditation, and I like people to be able to dig there’s a development, and not a static process.

Q: I’m still amazed at your readings, not just the impact you have on the audience, but your paper trail, book catalogues, albums, vinyl, first edition printings, out of print classics people want signed. It’s like “This Is Your Life” on parade.

A: Not quite. It’s my mind on parade. That’s what the mind is for, to show other people.

Q: It’s obvious that people want to be writers again. I feel that.

A: They want to express themselves. Not just to be a writer to be a writer, but they want to be able to say what they really think.

© 2021 Harvey Kubernik

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, published in 2014 and now available in six foreign language editions. Kubernik also authored Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For summer 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years)

This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century). Harvey is the Project Coordinator of The Jack Kerouac Collection, a box set of recordings.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

In summer of 2019, Harvey was interviewed for director Matt O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, Neil Finn, and producer Richard Dashut. Premiere broadcast was in 2020.

During 2020 he served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Kubernik is currently working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter Del Shannon.

Kubernik also appears as a screen interview subject for director/producer Neil Norman’s GNP Crescendo documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard. Jan Savage and Daryl Hooper original members of the Seeds participated along with Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, Iggy Pop, Kim Fowley, Jim Salzer, the Bangles, photographer Ed Caraeff, Mark Weitz of the Strawberry Alarm Clock and Johnny Echols of Love. Miss Pamela Des Barres supplied the narration. Norman’s documentary is scheduled for a debut broadcast on television during 2021 and then other retail platforms.

This decade Harvey was filmed for the currently in-production documentary about former Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross produced and directed by Brad Ross and Jonathan Rosenberg. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Shel Talmy, Don Peake, Kim Fowley, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.